FINCEN FILES

Global banks defy U.S. crackdowns by serving oligarchs, criminals and terrorists

The FinCEN Files show trillions in tainted dollars flow freely through major banks, swamping a broken enforcement system.

Secret U.S. government documents reveal that JPMorgan Chase, HSBC and other big banks have defied money laundering crackdowns by moving staggering sums of illicit cash for shadowy characters and criminal networks that have spread chaos and undermined democracy around the world.

The records show that five global banks — JPMorgan, HSBC, Standard Chartered Bank, Deutsche Bank and Bank of New York Mellon — kept profiting from powerful and dangerous players even after U.S. authorities fined these financial institutions for earlier failures to stem flows of dirty money.

U.S. agencies responsible for enforcing money laundering laws rarely prosecute megabanks that break the law, and the actions authorities do take barely ripple the flood of plundered money that washes through the international financial system.

In some cases the banks kept moving illicit funds even after U.S. officials warned them they’d face criminal prosecutions if they didn’t stop doing business with mobsters, fraudsters or corrupt regimes.

JPMorgan, the largest bank based in the United States, moved money for people and companies tied to the massive looting of public funds in Malaysia, Venezuela and Ukraine, the leaked documents reveal.

The bank moved more than $1 billion for the fugitive financier behind Malaysia’s 1MDB scandal, the records show, and more than $2 million for a young energy mogul’s company that has been accused of cheating Venezuela’s government and helping cause electrical blackouts that crippled large parts of the country.

JPMorgan also processed more than $50 million in payments over a decade, the records show, for Paul Manafort, the former campaign manager for President Donald Trump. The bank shuttled at least $6.9 million in Manafort transactions in the 14 months after he resigned from the campaign amid a swirl of money laundering and corruption allegations spawning from his work with a pro-Russian political party in Ukraine.

Tainted transactions continued to surge through accounts at JPMorgan despite the bank’s promises to improve its money laundering controls as part of settlements it reached with U.S. authorities in 2011, 2013 and 2014.

In response to questions for this story, JPMorgan said it was legally prohibited from discussing clients or transactions. It said it has taken a “leadership role” in pursuing “proactive intelligence-led investigations” and developing “innovative techniques to help combat financial crime.”

HSBC, Standard Chartered Bank, Deutsche Bank and Bank of New York Mellon also continued to wave through suspect payments despite similar promises to government authorities, the secret documents show.

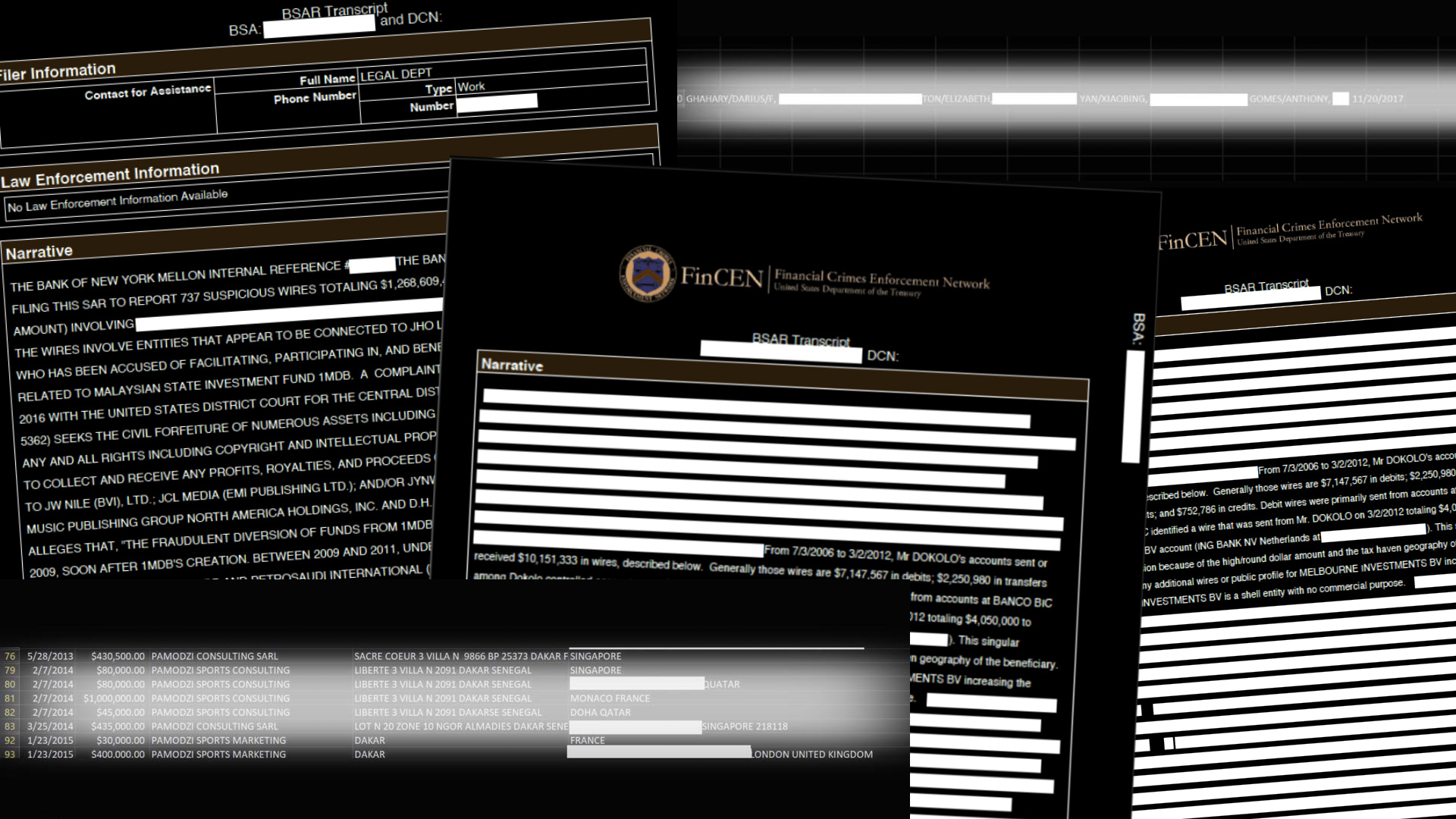

The leaked documents, known as the FinCEN Files, include more than 2,100 suspicious activity reports filed by banks and other financial firms with the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. The agency, known in shorthand as FinCEN, is an intelligence unit at the heart of the global system to fight money laundering.

BuzzFeed News obtained the records and shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. ICIJ organized a team of more than 400 journalists from 110 news organizations in 88 countries to investigate the world of banks and money laundering.

In all, an ICIJ analysis found, the documents identify more than $2 trillion in transactions between 1999 and 2017 that were flagged by financial institutions’ internal compliance officers as possible money laundering or other criminal activity — including $514 billion at JPMorgan and $1.3 trillion at Deutsche Bank.

Suspicious activity reports reflect the concerns of watchdogs within banks and are not necessarily evidence of criminal conduct or other wrongdoing.

Financial institutions have abandoned their roles as front-line defenses against money laundering. – Paul Pelletier

Though a vast amount, the $2 trillion in suspicious transactions identified within this set of documents is just a drop in a far larger flood of dirty money gushing through banks around the world. The FinCEN Files represent less than 0.02% of the more than 12 million suspicious activity reports that financial institutions filed with FinCEN between 2011 and 2017.

FinCEN and its parent, the Treasury Department, did not answer a series of questions sent last month by ICIJ and its partners. FinCEN told BuzzFeed News that it does not comment on the “existence or non-existence” of specific suspicious activity reports, sometimes known as SARs. Days before the release of the investigation by ICIJ and its partners, FinCEN announced that it was seeking public comments on ways to improve the U.S.’s anti-money laundering system.

The cache of suspicious activity reports — along with hundreds of spreadsheets filled with names, dates and figures — flag bank clients in more than 170 countries and territories who were identified as being involved in potentially illicit transactions.

Along with sifting through the FinCEN Files, ICIJ and its media partners obtained more than 17,600 other records from insiders and whistleblowers, court files, freedom-of-information requests and other sources. The team interviewed hundreds of people, including financial crime experts, law enforcement officials and crime victims.

According to BuzzFeed News, some of the secret records were requested as part of U.S. congressional investigations into Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Others were gathered by FinCEN following requests from law enforcement agencies, BuzzFeed said.

The FinCEN Files offer unprecedented insight into a secret world of international banking, anonymous clients and, in many cases, financial crime.

They show banks blindly moving cash through their accounts for people they can’t identify, failing to report transactions with all the hallmarks of money laundering until years after the fact, even doing business with clients enmeshed in financial frauds and public corruption scandals.

Authorities in the U.S., who play a leading role in the global battle against money laundering, have ordered big banks to reform their practices, fined them hundreds of millions and even billions of dollars, and held threats of criminal charges over them as part of so-called deferred prosecution agreements.

A 16-month investigation by ICIJ and its reporting partners shows that these headline-making tactics haven’t worked. Big banks continue to play a central role in moving money tied to corruption, fraud, organized crime and terrorism.

“By utterly failing to prevent large-scale corrupt transactions, financial institutions have abandoned their roles as front-line defenses against money laundering,” Paul Pelletier, a former senior U.S. Justice Department official and financial crimes prosecutor, told ICIJ.

He said banks know that “they operate in a system that is largely toothless.”

Five of the banks that appear most often in the FinCEN Files — Deutsche Bank, Bank of New York Mellon, Standard Chartered, JPMorgan and HSBC — repeatedly violated their official promises of good behavior, the secret records show.

In 2012, London-based HSBC, the largest bank in Europe, signed a deferred prosecution deal and admitted it had laundered at least $881 million for Latin American drug cartels. Narcotraffickers used specially shaped boxes that fit HSBC’s teller windows to drop off the huge amounts of drug money they were pushing through the financial system.

Under the deal with prosecutors, HSBC paid $1.9 billion and the government agreed to put criminal charges against the bank on hold and dismiss them after five years if HSBC kept its pledge to aggressively fight the flow of dirty money.

During that five-year probationary period, the FinCEN Files show, HSBC continued to move money for questionable characters, including suspected Russian money launderers and a Ponzi scheme under investigation in multiple countries.

Yet the government allowed HSBC to announce in December 2017 that it had “lived up to all of its commitments” under its deferred prosecution pact — and that prosecutors were dismissing the criminal charges for good.

In a statement to ICIJ, HSBC declined to answer questions about specific customers or transactions. HSBC said ICIJ’s information is “historic and predates” the end of its five-year deferred prosecution deal. During that time, the bank said, it “embarked on a multi-year journey to overhaul its ability to combat financial crime. . . . HSBC is a much safer institution than it was in 2012.”

HSBC noted that in deciding to release the bank from the threat of criminal charges, the government had access to reports from a monitor who reviewed the bank’s reforms and practices.

The Department of Justice declined to answer specific questions. In a statement, a spokesperson for the department’s criminal division said:

“The Department of Justice stands by its work, and remains committed to aggressively investigating and prosecuting financial crime — including money laundering — wherever we find it.”

‘Everyone is doing badly’: Dirty money swamps bureaucrats

Money laundering isn’t a victimless crime.

The free flow of dirty cash helps sustain criminal gangs and destabilize nations. And it is a driver of global economic inequality. Laundered funds are often shunted between accounts owned by obscure shell companies registered in secretive offshore tax havens, allowing elites to hide massive sums from law enforcement and tax authorities.

An ICIJ analysis found that banks in the FinCEN files regularly processed transactions to companies registered in so-called secrecy jurisdictions and did so without knowing the ultimate owner of the account. At least 20% of the reports contained a client with an address in one of the world’s top offshore financial havens, the British Virgin Islands, while many others provided addresses in the U.K., the U.S., Cyprus, Hong Kong, the United Arab Emirates, Russia and Switzerland.

ICIJ’s analysis found that in half of the reports banks didn’t have information about one or more entities behind the transactions. In 160 reports, banks sought more information about corporate vehicles, only to be met with no response.

Estimates by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime indicate that $2.4 trillion in illicit funds are laundered each year — the equivalent of nearly 2.7% of all goods and services produced annually in the world. But the agency estimates that authorities detect less than 1% of the world’s dirty money.

“Everyone is doing badly,” David Lewis, executive secretary of the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force, a partnership of governments around the world that sets anti-money laundering standards, acknowledged in an interview with ICIJ.

His organization’s country-evaluation reports — which dig into how well banks and government agencies meet anti-money-laundering laws and regulations — show lots of box-checking but little practical progress. Many countries seem more concerned with looking good on paper than actually cracking down on money laundering, he said.

Even an association of the world’s biggest banks complained last year that regulators focus on “technical compliance” rather than whether systems “are really making a difference in the fight against financial crime.”

A Bombing in Jerusalem

For some financial institutions, the problem client is another bank.

One early morning in 2003 Steven Averbach was on the No. 6 bus in Jerusalem, when a man rushed to board as the bus pulled away.

“There were too many things out of place” with the man, recalled Averbach, who grew up in New Jersey but immigrated to Israel as a teenager. The man wore long black pants, a white shirt and a black jacket, the typical garb of an Orthodox Jew. But he wore “tipped shoes” that didn’t fit with the Orthodox sect dress, and his jacket was bulging.

In his right hand was a device that looked like a doorbell.

Averbach, who had previously served as chief weapons instructor for the Jerusalem police force, drew his sidearm. But as the ex-cop turned to face the man, “he detonated himself,” Averbach later testified in a video deposition.

The blast killed seven and wounded 20 others, leaving Averbach paralyzed from the neck down. He died in 2010 of complications from the long-term effects of his injuries.

By then, he and his family had become plaintiffs in a lawsuit in the U.S. accusing a Jordanian financial institution, Arab Bank, of moving funds that helped bankroll terrorists involved in the bus bombing and other attacks.

The FinCEN Files show that as the litigation was casting a shadow over Arab Bank, it was benefiting from a working relationship with a much bigger, more influential bank: Standard Chartered.

The U.K.-headquartered bank helped Arab Bank clients access the U.S. financial system after regulators found deficiencies in Arab Bank’s money laundering controls in 2005 and forced it to curtail its money-transfer activities in the U.S.

Standard Chartered continued its relationship with Arab Bank as the lawsuit against the Jordanian bank worked its way through U.S. courts — and even after American authorities put Standard Chartered on notice that it must stop processing transactions for suspect clients.

New York regulators concluded in 2012 that Standard Chartered had “schemed with the Government of Iran” for nearly a decade to push through $250 billion in secret transactions, reaping “hundreds of millions of dollars in fees” and leaving “the U.S. financial system vulnerable to terrorists, weapons dealers, drug kingpins and corrupt regimes.” This pattern of conduct cost Standard Chartered nearly $670 million in penalties in the second half of 2012 as part of two deferred prosecution agreements and other deals with New York and U.S. authorities.

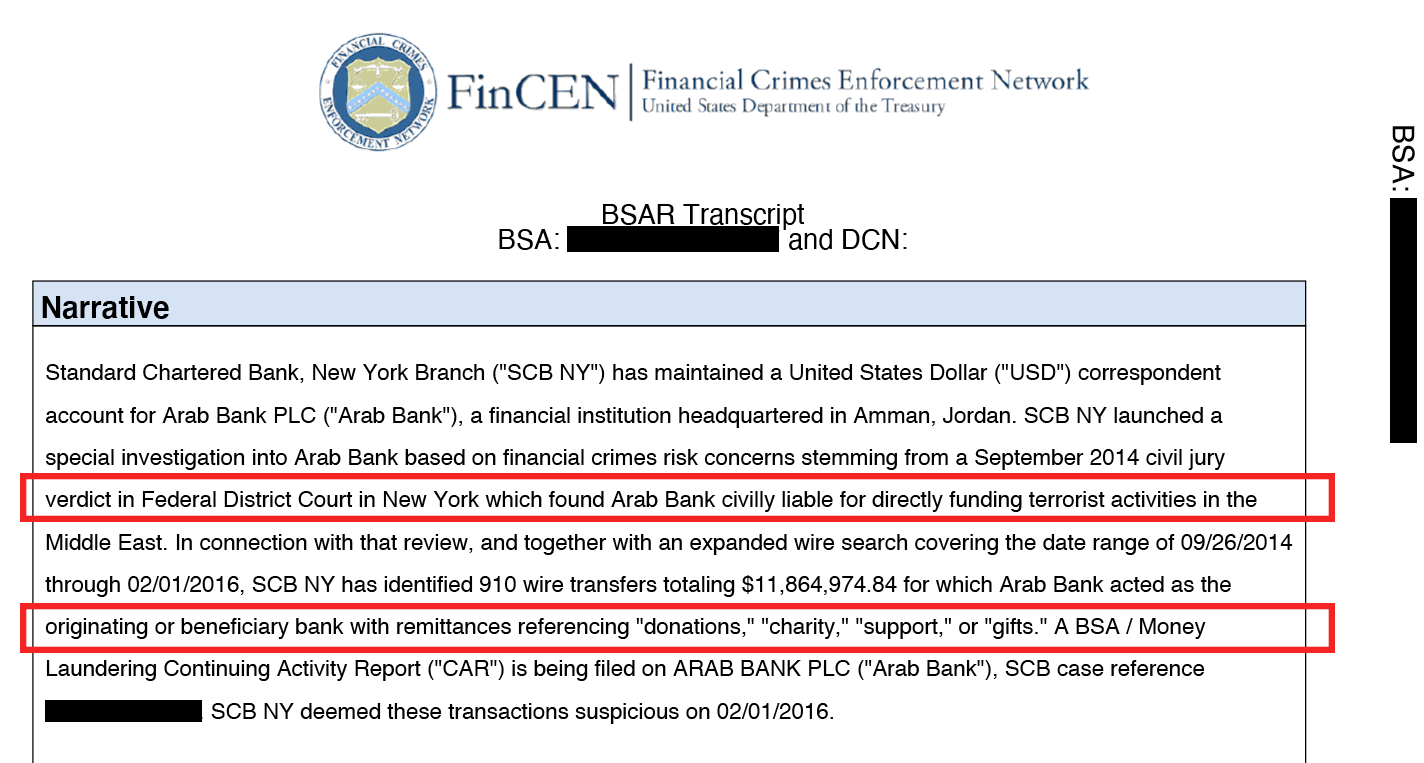

Despite its official pledges to stay away from suspect customers, Standard Chartered processed 2,055 transactions totaling more than $24 million for Arab Bank customers between September 2013 and September 2014, the FinCEN Files show.

Then, in late September 2014, Standard Chartered got another reason to back away from Arab Bank. In the lawsuit stemming from the 2003 Jerusalem bus bombing and other attacks, a jury in Brooklyn found Arab Bank liable for knowingly supporting terrorism by transmitting money disguised as charitable donations for the benefit of Hamas, the Palestinian militant group that the U.S. classifies as a terrorist organization.

More than a year later, compliance staffers at Standard Chartered sent FinCEN a suspicious activity report acknowledging the bank’s dealings with Arab Bank up to a few days after the verdict in Brooklyn and expressing concerns about “potential terrorist financing.”

But that wasn’t the end of it.

Standard Chartered shifted nearly $12 million more in transactions for Arab Bank customers from just after the verdict until February 2016, according to a follow-up suspicious activity report included in the FinCEN Files. Many wires referred to “charities,” “donations,” “support” or “gifts,” the bank said.

The follow-up report noted that the payment records raised concerns — as in the Brooklyn trial — that “illicit activities” were being potentially funded “under the guise of charity.”

The civil verdict against Arab Bank was overturned when an appeals court found flaws in the trial judge’s jury instructions. Arab Bank then settled with nearly 600 victims and victims’ relatives for an undisclosed amount.

In a statement, Arab Bank told ICIJ it “abhors terrorism and does not support or encourage terrorist activities.” The bank said that allegations against it date back nearly 20 years to a time when anti-money-laundering laws, tools and technologies were different than they are now.

“In every country where it operates, Arab Bank is in good standing with government regulators and complies with anti-terrorism and money laundering laws,” the bank said. The 2005 U.S. regulatory limits against the bank were formally lifted in 2018.

Standard Chartered told the BBC, a partner of ICIJ, that it “initiated account closure” in connection to Arab Bank shortly after the jury verdict. “This process can take time in some cases,” the bank said, “but in all cases the bank continues to fulfil its regulatory obligations” while exiting accounts.

Arab Bank noted it “enjoys a longstanding relationship with Standard Chartered” that “continues today.”

Standard Chartered no longer processes U.S. dollar transactions for Arab Bank, but it still provides other banking services for the Jordanian financial institution, Arab Bank told ICIJ.

Rewards and risks

Why do banks move suspect money? Because it’s profitable.

Banks can pad their bottom lines with the fees they collect as money spins through the webs of accounts often maintained by corrupt users of the financial system. JPMorgan, for example, scored an estimated half a billion dollars in revenues by serving as the chief banker to Bernie Madoff, according to filings in the bankruptcy case spawned by the collapse of his multi-billion-dollar Ponzi scheme.

Dealing with shady customers does carry risks.

JPMorgan paid $88.3 million in 2011 to settle regulators’ claims that it had violated economic sanctions against Iran and other countries under U.S. embargoes. Treasury officials hit the bank with a “cease and desist” order in 2013 that described “systemic deficiencies” in its anti-money-laundering efforts, noting the bank had “failed to identify significant volumes of suspicious activity.”

Then, in January 2014, the bank paid $2.6 billion to U.S. agencies to settle investigations over its role in Madoff’s scheme. JPMorgan posted profits of more than double that amount in just that quarter on its way to nearly $22 billion in profits for the year. Madoff pleaded guilty and is serving a 150-year sentence in federal prison.

JPMorgan continued, after those enforcement actions, to move money for people involved in alleged financial crimes, the FinCEN Files show.

Among them: Jho Low, a financier accused by authorities in multiple countries of being the mastermind behind the embezzlement of more than $4.5 billion from a Malaysian economic development fund, called 1Malaysia Development Berhad, or 1MDB. He moved just over $1.2 billion through JPMorgan from 2013 to 2016, the records show.

Low first gained notoriety for partying with Paris Hilton, Leonardo DiCaprio and other celebrities. One night at a club on the French Riviera, he got into a bidding war over a cache of Cristal champagne — winning the contest with a final bid of 2 million euros, according to “Billion Dollar Whale,” a bestselling book about the 1MDB swindle.

He was first outed by media reports in early 2015 as a key figure in the 1MDB scandal, the so-called “heist of the century.” Singapore issued a warrant for his arrest in April 2016. Authorities in the U.S., Malaysia and Singapore are seeking his capture.

JPMorgan also moved money for companies and people tied to corruption scandals in Venezuela that have helped create one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. One in three Venezuelans is not getting enough to eat, the UN reported this year, and millions have fled the country.

One of the Venezuelans who got help from JPMorgan was Alejandro “Piojo” Isturiz, a former government official who has been charged by U.S. authorities as a player in an international money laundering scheme. Prosecutors allege that between 2011 and 2013 Isturiz and others solicited bribes to rig government energy contracts. The bank moved more than $63 million for companies linked to Isturiz and the money laundering scheme between 2012 and 2016, the FinCEN Files show.

Isturiz could not be reached for comment.

The secret records show that JPMorgan also provided banking services to Derwick Associates, an energy firm that won billions of dollars in no-bid contracts to repair Venezuela’s failing electricity grid. A 2018 analysis by the Venezuelan chapter of the nonprofit group Transparency International concluded that Derwick Associates failed to deliver the power capacity expected — and overbilled the Venezuelan government by at least $2.9 billion.

Alejandro Betancourt was in his 20s when he co-founded Derwick with a younger cousin.

News articles and Internet postings from 2011 raised allegations about Derwick. The company later filed a lawsuit that claimed it was the victim of a smear campaign that falsely accused it of being part of a “criminal group.” The suit was settled on undisclosed terms.

The FinCEN Files show that Derwick used accounts at JPMorgan to move at least $2.1 million in 2011 and 2012 and that the bank processed other transactions of undisclosed amounts for Derwick and its managers at least into 2013.

In 2018, the U.S. Justice Department charged a senior Derwick executive, Francisco Convit Guruceaga, in an alleged $1.2 billion bribery and money-laundering scheme. Betancourt was cited in the criminal complaint as an unnamed co-conspirator, the Miami Herald, an ICIJ partner, later reported.

A lawyer for Betancourt said: “My client denies any wrongdoing.” Convit’s attorney declined to comment.

In a general statement, JPMorgan noted that it had acknowledged in 2014 that it needed to improve its anti-money-laundering controls and that since then it has invested heavily toward this effort.

“Today, thousands of employees and hundreds of millions of dollars are devoted to helping support law enforcement and national security efforts,” the bank said.

‘Boss of bosses’

Often, the secret files show, banks handling cross-border transactions have little idea who they’re dealing with — even when they’re shifting hundreds of millions of dollars.

Take the case of a mysterious shell company called ABSI Enterprises. ABSI sent and received more than $1 billion in transactions through JPMorgan between January 2010 and July 2015, the FinCEN Files show.

This amount included transactions through a direct bank account with JPMorgan, which ABSI closed in 2013, and through so-called correspondent banking arrangements, in which a bank with significant U.S. operations, such as JPMorgan, allows foreign banks to process U.S. dollar transactions through its own accounts.

Compliance watchdogs based at the bank’s Columbus, Ohio, operations hub decided to try to figure out ABSI’s actual owner in 2015 after a Russian news site reported that a similarly-named shell company — which JPMorgan’s records indicated was the parent of ABSI — was linked to an underworld figure named Semion Mogilevich.

Mogilevich has been described as the “Boss of Bosses” of Russia mafia groups. When the FBI put him on its Top Ten Most Wanted list in 2009, it said his criminal network was involved in weapons and drug trafficking, extortion and contract murders. The chain-smoking, beefy Ukrainian’s signature method of neutralizing an enemy, The Guardian once reported, is the car bomb.

The records show the compliance officers searched in vain through their files on the shell company, unable to determine who was behind the firm or what its true purpose was.

While those details still remain unclear, JPMorgan had plenty of reasons to examine ABSI years earlier: it operated as a shell company in Cyprus, considered a major money laundering center at the time, and it was directing hundreds of millions of dollars through JPMorgan.

Mogilevich is featured in “World’s Most Wanted,” a Netflix documentary series released in August.

Through a spokesperson, Mogilevich said he had no knowledge of ABSI.

He has previously said: “I am not a leader or an active participant of any criminal group.”

The mighty dollar

BuzzFeed News used the cache of suspicious activity reports in 2018 to publish stories revealing secret payments to shell companies controlled by Manafort, who is now serving a federal prison sentence in home confinement in a case based largely on these transactions.

A former U.S. Treasury Department official, Natalie Mayflower Sours Edwards, pleaded guilty in January to conspiring to unlawfully disclose FinCEN documents to BuzzFeed News.

BuzzFeed News has not commented on its source.

FinCEN and other U.S. agencies play an outsized role in anti-money-laundering efforts around the world, largely because money launderers and other criminals share the same goal as many bank customers who operate across borders: moving U.S. dollars, the de facto global currency, between account holders in different countries.

An elite group of mostly U.S. and European banks with large operations in New York pocket fees for performing this trick, drawing on their privileged access to the U.S. Federal Reserve. These banks’ U.S. operations can also help turn local money into U.S. dollars, another key money laundering goal.

American law entrusts banks with frontline responsibility to prevent money laundering, even though their financial incentives run entirely in the direction of keeping money — dirty or clean — moving. While banks are empowered to stop a transaction if it appears to be shady, they’re not necessarily required to do so. They simply have to file a suspicious activity report with FinCEN.

FinCEN, which has roughly 270 employees, collects and sifts through more than two million new suspicious activity reports each year from banks and other financial firms. It shares information with U.S. law enforcement agencies and with financial intelligence units in other countries.

Long gone

Inside big banks, systems for sniffing out illicit cash flows rely on overworked, under-resourced staffers, who typically work in back offices far from headquarters and have little clout within their organizations. Documents in the FinCEN Files show compliance workers at major banks often resort to basic Google searches to try to learn who’s behind transfers involving hundreds of millions of dollars.

As a result, the secret documents show, banks frequently file suspicious activity reports only after a transaction or customer becomes the subject of a negative news article or a government inquiry — usually after the money is long gone.

In interviews with ICIJ and BuzzFeed, more than a dozen former compliance officers at HSBC called into question the effectiveness of the bank’s anti-money-laundering programs. Some said the bank didn’t give them enough time to do much beyond cursory looks at large flows of cash — and that when they requested information about who was behind big transactions, HSBC branches outside the U.S. often ignored them.

“They would say: ‘Sure, we’ll get back to you.’ But they’d never get back,” recalls Alexis Grullon, who monitored international suspicious activity for HSBC in New York from 2012 to 2014.

At Standard Chartered Bank, a lawsuit filed in December 2019 in federal court in New York claims, employees who objected to illegal transactions weren’t ignored — they were threatened, harassed and fired.

Julian Knight and Anshuman Chandra claim in the suit that they were forced out of management jobs at the bank after it learned they had cooperated with an FBI probe into transfers of money that Standard Chartered had pushed through for U.S.-sanctioned entities from Iran, Libya, Sudan and Myanmar.

Standard Chartered, the suit claims, engaged in a “highly sophisticated money laundering scheme,” altering the names of parties subject to U.S. sanctions on transaction documents and creating a technological workaround that allowed illegal transactions to slip through the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank undetected.

Chandra, who worked in the bank’s Dubai branch from 2011 to 2016, concluded that the sanctions busting helped bankroll terror attacks “that killed and wounded soldiers serving in the U.S.-led coalition, as well as many innocent civilians.”

The suit says the scheme allowed the bank to profit from the “high premium” that Iran and its operatives were willing to pay to convert Iranian rials — the country’s sanctions-depressed currency — into dollars.

“You can run a show like this probably for a few months without being caught if it’s a small group running it within the bank,” Chandra said in an interview with ICIJ partner BuzzFeed News. “But something like this happening over a period of years and coming into billions of dollars — someone at the top should have asked the question: How are we making this money?”

Chandra and Knight claim that the bank acknowledged only a fraction of its violations and lied about when illegal transactions had stopped when it came forward and admitted sanctions violations as part of its 2012 deferred prosecution deal with U.S. authorities.

The agency extended the bank’s probationary period again and again over several years. Then, in 2019, the bank paid $1.1 billion more for continuing violations of sanctions against Iran and other countries and agreed to extend its deferred prosecution pact for two more years.

In court papers, Standard Chartered says the ex-employees’ allegations are implausible and meritless. In a statement to ICIJ, the bank said: “These false allegations have been thoroughly discredited by the U.S. authorities who undertook a comprehensive investigation into the claims.”

The bank noted that a U.S. judge had dismissed a related lawsuit in July. In that case, U.S. prosecutors said in a legal filing that federal agencies couldn’t find evidence to support Knight’s claim that Standard Chartered had continued violating sanctions on behalf Iranian clients after 2007.

‘I am dying’: Ukraine, JPMorgan and the kleptocrats

Twenty-one-year-old Olesia Zhukovska took a bullet in the fight against corruption in Ukraine.

She’d been working as a nurse in western Ukraine in late 2013 when protests broke out in the heart of Kyiv, the capital. During the regime of President Viktor Yanukovych, billions of dollars were being smuggled out of the country — channeled through far-off accounts at some of the world’s biggest banks.

Demonstrators protested their leaders’ tilt toward Russia and the high-level corruption that was wrecking the country’s economy, its schools, its health system. Ukrainians were dying, patient advocates said, because money intended for life-saving medicines and equipment was being stolen by insiders.

Zhukovska says she couldn’t afford the $3,000 bribe it would take to get a job in an urban hospital. She worked instead at a rural health center with no heat, no medicines. “Nothing,” she says. The structure “looked like an old ruin.”

In December 2013, she joined growing anti-government rallies in Kyiv, volunteering to treat demonstrators beaten by baton-swinging government forces.

She was sorting bandages on Feb. 20, 2014, when a sniper’s bullet tore into her neck. It hit less than an inch, she says, from her carotid artery.

As an ambulance rushed her to the hospital, she tweeted: “I am dying.”

Я вмираю

— Olesya Zhukovskaya (@OlesyaZhukovska) February 20, 2014

It was the day of what became known as the “Snipers’ Massacre.” When the day ended, Zhukovska had survived, but dozens of others had been killed by rooftop police snipers who rained fire on protesters.

Zhukovska’s tale of struggle and pain is similar to the stories of average people around the world who suffer as corrupt politicians and their cronies — in Ukraine and beyond — enrich themselves with the help of name-brand banks with global footprints.

As the young nurse was still healing in a hospital in early 2014, Yanukovych fled the country. So did his closest adviser, Chief of Staff Andriy Klyuyev, who had emerged as a despised face of the crackdown.

Both ended up in exile in Russia. Both are wanted by Ukrainian authorities and under U.S. sanctions that accuse them of embezzling public funds and subverting Ukrainian democracy.

An investigation later found that a solar energy group run by Klyuyev’s family, Activ Solar, made off with hundreds of millions of dollars in what were purportedly loans from government-owned banks. Its assets were funneled into a network of offshore companies controlled by Klyuyev family members, according to a report by Ukraine’s Financial Intelligence Unit as part of a multinational investigation into the Yanukovych regime.

The Activ Solar affair was part of an orgy of corruption under Yanukovych that included a network of companies linked to Klyuyev’s brother, Serhiy, buying Ukraine’s presidential palace, the Mezhyhirya estate, where Yanukovych lived, for a rock-bottom price. The palace — with a zoo complete with ostriches and a replica of a Spanish galleon for cruises on the Dnieper River — became a symbol of the regime’s decadence.

As always, corrupt proceeds need a place to hide. On the way, most pass through Lower Manhattan.

Lingerie and knee Boots

In January 2010, the same time Yanukovych was winning the first round of Ukraine’s presidential election, someone incorporated a new company at the U.K.’s corporate registry, Companies House, a government office long criticized for granting legitimacy to companies with secret owners.

The new company, NoviRex Sales LLP, claimed to be in the “domestic appliances” business, but its paperwork suggested something else was going on.

It listed its official address as a small shop in Cardiff, Wales. Recently occupied by a nail salon, the same address was used by hundreds of other companies registered at Companies House.

NoviRex’s listed owners were two other companies, both incorporated in the British Virgin Islands and also without visible owners. The same two BVI companies were listed as “owners” of thousands more companies at Companies House — many registered to the same shop in Cardiff.

Records show that the two companies that owned NoviRex also owned companies linked in news reports to suspected bid-rigging and other corrupt acts, much of it centering on Ukraine.

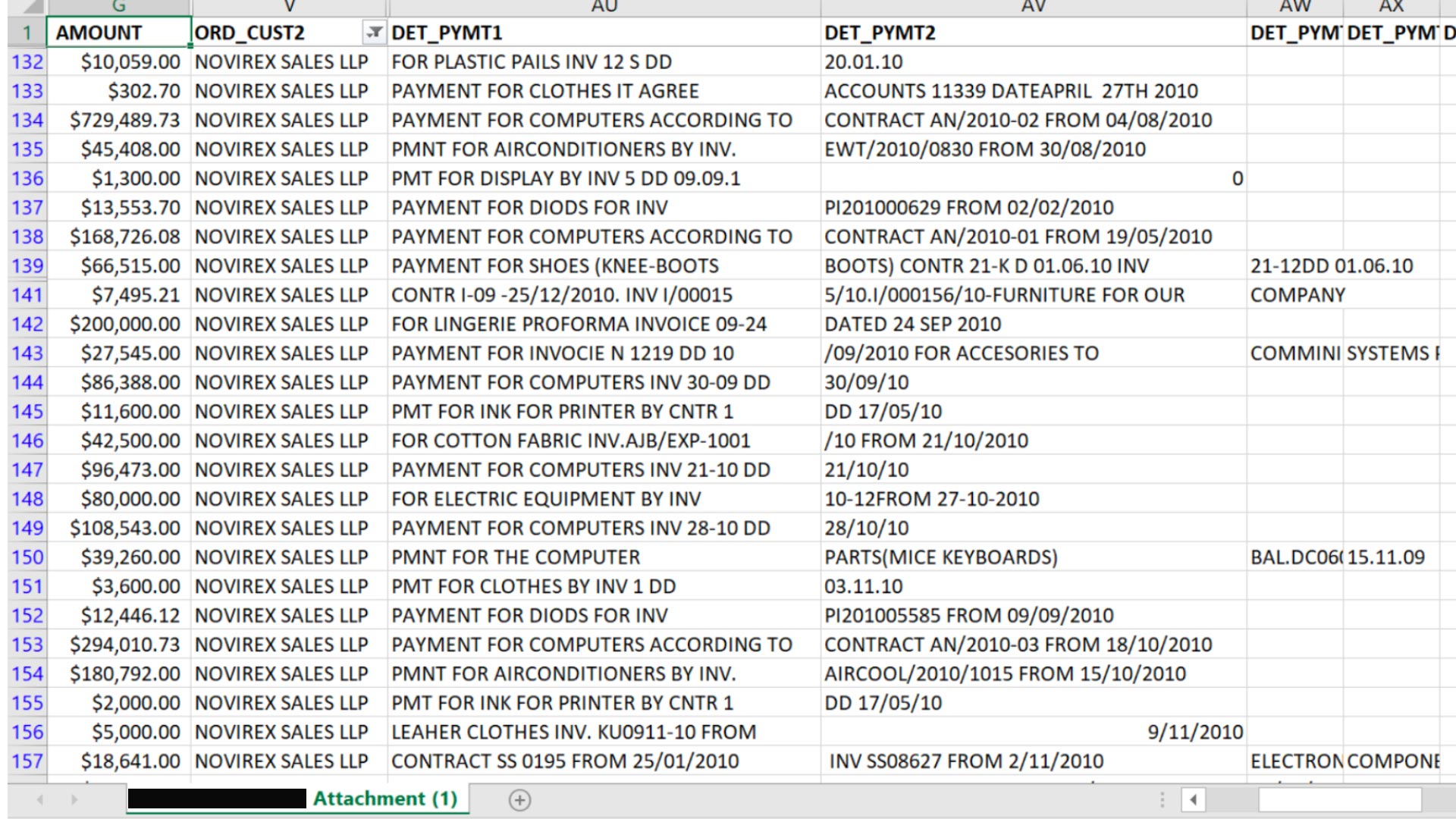

The FinCEN Files show NoviRex soon began firing off payments of astonishing size and frequency. For a domestic appliances business, some of the reasons NoviRex gave for the payments were strange: $200,000 for “lingerie” from a British Virgin Islands company … $34,000 for “keyboard stickers” from a Hong Kong firm … almost $400,000 on “knee-boots” from another Hong Kong company.

Yet as NoviRex moved millions of dollars through the global banking system, its financial statements — available online from Companies House — indicated it was basically moribund, spending less than $2,500 a year.

NoviRex sent all its payments from banks in notorious money-laundering centers, including Latvia’s ABLV Bank.

But to move dollars internationally, NoviRex needed more than dodgy Latvian banks. It needed a global institution with access to accounts with the New York branch of the U.S. Federal Reserve System.

NoviRex needed JPMorgan Chase.

The Middleman

With roots dating to American Revolutionary era figures Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, the global banking behemoth provided ABLV with a U.S. dollar account in New York, allowing the Latvian bank to, in turn, offer dollar accounts to its own customers, including NoviRex.

In the early 2000s, even as banks faced new obligations under the 2001 USA Patriot Act to carefully check out their foreign banking partners, JPMorgan ramped up business supplying U.S. dollar accounts to foreign banks. By 2003, it had become the global leader in “correspondent banking,” processing payments for the clients of 3,500 other banks around the world, helping bring JPMorgan’s overall daily dollar transaction volume to more than $2 trillion for clients in 46 countries.

In 2004, FinCEN issued a warning to global banks about Eastern European banks and their shell company customers, reporting that $4 billion in suspicious transactions had been reported since 1996.

In 2005, the year Jamie Dimon was named JPMorgan’s chief executive, FinCEN warned that Latvian banks and their “sizable” non-Latvian customer base “continue to pose significant money laundering risks.” FinCEN said: “Many of Latvia’s institutions do not appear to serve the Latvian community, but instead serve suspect foreign private shell companies.” FinCEN said Latvia’s 23 banks then held about $5 billion in “nonresident” deposits, mainly from Russia and other parts of the former Soviet Union.

This was JPMorgan’s market.

In allowing a transfer, a correspondent bank (in a simple case) deducts the amount from the account of the sending bank and credits the account of the receiving bank, taking a fee.

By granting foreign banks access to U.S. dollars, JPMorgan was opening the system’s doors to their customers, including anonymous shell companies like NoviRex.

In return for this gatekeeping power, and the fees it brings, U.S. law requires JPMorgan and other banks like it to monitor each transaction cleared on foreign banks’ instructions — and to vet the foreign banks it does business with.

A later probe would find that 90% of ABLV customers were deemed “high risk” by ABLV itself, primarily because they were shell companies registered in secrecy jurisdictions.

Some of these shells were moving billions of dollars later traced to corruption in Ukraine. U.S. regulators concluded ABLV had institutionalized money laundering as “a pillar of the bank’s business practices,” aggressively peddled money laundering schemes to clients, and produced fraudulent documentation of “the highest quality” to support these schemes — all the while bribing Latvian officials to protect the bank from any threats to its business model.

Two financial crime experts who reviewed NoviRex’s transactions at ICIJ’s request said the signs of money laundering were clear. NoviRex had behaved like no legitimate business ever would.

“If I was at JPMorgan and I saw this, I’d be thinking: ‘This is horrendous,’ ” one of the experts, former U.K. police detective Martin Woods, said. “What normal company buys computers, lingerie and buckets?”

By early 2014, as citizens were filling the streets to protest Yanukovych, Klyuyev and other government leaders, NoviRex had moved more than $188 million in transactions via JPMorgan.

Pulling out

JPMorgan, meanwhile, was moving on.

By the end of 2014 it had terminated correspondent accounts of about 500 foreign banks, including, according to a Latvian banking trade group official, banks in Latvia.

In a December 2014 report to shareholders, the bank acknowledged “mistakes made and lessons learned from our experiences in foreign correspondent banking.”

“Every company makes mistakes (and we’ve made a number of them), but the hallmark of a great company is what it does in response,” Dimon, the CEO, wrote in a cover letter. He didn’t mention Ukraine or Latvia, or ABLV or NoviRex.

Nor did he mention that, shortly before the pullout, U.S. regulators had issued a scathing appraisal of JPMorgan’s money laundering safeguards and ordered the bank to review its correspondent banking practices.

By then, Ukraine’s treasury had been looted, JPMorgan’s fees pocketed. JPMorgan’s treasury-services group, the parent of its correspondent-banking business, reported $4.13 billion in revenue in 2013. Dimon’s total compensation in 2014 was $20 million.

The NoviRex story might have ended there.

But then, in November 2016, Donald Trump was elected America’s 45th president. Soon after, the U.S. Justice Department appointed Robert Mueller as special counsel to investigate Russia’s election interference and other issues relating to Trump and his associates.

One of those associates was Paul Manafort, onetime chairman of Trump’s presidential campaign.

Death Penalty

Manafort had also served as a consultant and lobbyist for Ukraine’s former president, Yanukovych. The FinCEN Files show staff at JPMorgan’s Columbus, Ohio, compliance office became concerned about press reports from Ukraine of secret payments to Manafort-controlled shell companies disguised as payments for computer equipment.

The bank noted that NoviRex had made such payments.

As scrutiny of Manafort’s foreign dealings intensified, the FinCEN Files show, JPMorgan filed more suspicious activity reports detailing — years after the fact — millions of dollars in payments to the consultant, his associates and their businesses.

At Manafort’s 2018 trial, NoviRex’s name surfaced as one of a handful of shell companies used by Ukrainian oligarchs to channel payments for political lobbying work to Manafort’s own shell companies.

In all, NoviRex secretly paid $4,190,111 to Manafort’s consulting operation on behalf of Yanukovych’s Party of the Regions, according to government exhibits in his trial.

Manafort was ultimately convicted of bank fraud, failure to report a foreign bank account and other crimes.

At one of Manafort’s trials, his former business partner, Rick Gates, finally revealed the person he understood to be behind NoviRex: Klyuyev, Yanukovych’s right-hand man.

Klyuyev denies this and claims that until recent press reports he “had no knowledge of the existence of the company Novirex Sales LLP.”

The help that JPMorgan provided Klyuyev’s company never came up during the trial.

In all, the FinCEN Files show, JPMorgan transmitted 706 transactions totaling at least $230 million for NoviRex from 2010 to 2015. Much of that amount went to companies incorporated in secretive tax havens.

In 2018, FinCEN declared JPMorgan’s former customer, ABLV, a “primary money laundering concern” that had moved “billions of dollars” for Ukrainian tycoons accused of looting state assets. FinCEN barred U.S. banks from providing ABLV access to U.S. correspondent accounts — a step known in financial circles as the “death penalty.” It is now in liquidation, and some of its bankers have been arrested by Latvian authorities.

In response to questions from ICIJ, an ABLV spokesperson said that during the liquidation, an auditor is carrying out a review of the bank’s ex-clients and their transactions.

She added: “We cannot publicly comment regarding any specific legal or natural persons.”

‘Tricks and cunning’: Big penalties don’t stop banks from moving dirty cash

Money streamed in from California, Peru, Bolivia, China and other places where low-income families were willing to sink their modest savings — $2,000, $5,000, $10,000 — into an investment they hoped would change their lives.

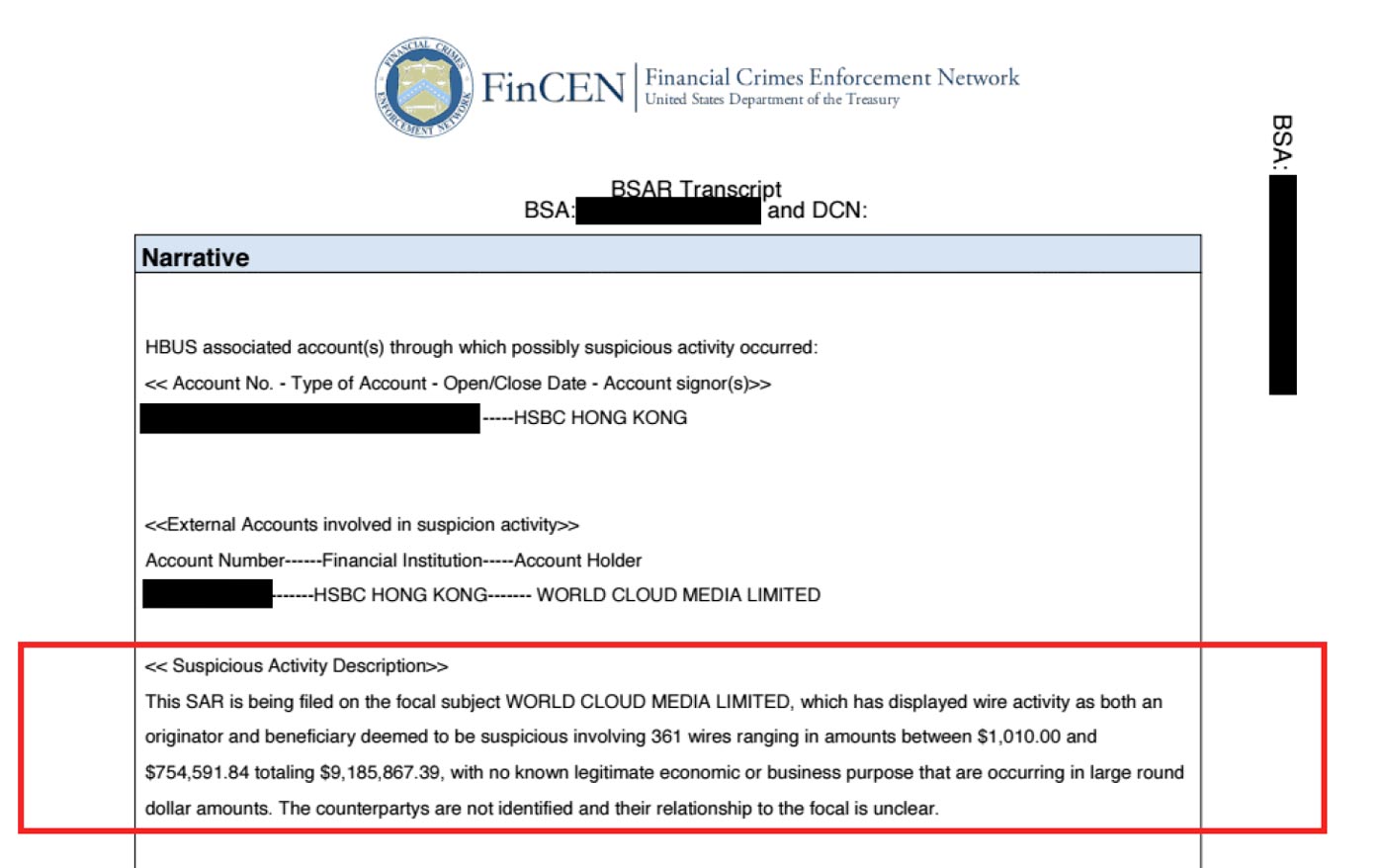

With the click of a keyboard, investors’ money funneled through the New York operations of global banking giant HSBC. Then it zipped across the world into accounts at HSBC’s sprawling Hong Kong offices.

Like others taken in by what became known as the World Capital Market Ponzi scheme, Reynaldo Pacheco, a 44-year-old father in Santa Rosa, California, promoted the deal to family and acquaintances. When the WCM scheme began to unravel, one of the unlucky investors he’d encouraged to put money into the deal decided to have him killed.

Three men kidnapped him and beat his head with rocks, leaving him dead in a creekbed, his hands tied behind his back with tape and one of his shoelaces.

Thousands of victims lost an estimated $80 million in the scheme.

The FinCEN Files show that HSBC continued shifting money for the WCM investment fund at a time when authorities in three countries were investigating the company and the bank’s internal watchdogs knew it was an alleged Ponzi scheme. More than $30 million tied to WCM flowed through the bank in 2013 and 2014 — at a time when HSBC was under probation as part of its deferred prosecution deal with American authorities.

Even after U.S. securities regulators won a restraining order freezing the company’s assets, WCM’s account at HSBC Hong Kong stayed active. According to court documents later filed by attorneys seeking money for the scheme’s victims, WCM drained more than $7 million from the account during the following week, drawing its balance to zero.

WCM wasn’t the only company tied to criminal activities that moved money through HSBC during the five-year probation that came with the bank’s $1.9 billion deferred prosecution deal. The bank’s Hong Kong office, for example, processed more than $900 million in transactions involving shell companies linked in court records and media reports to alleged criminal networks, an ICIJ analysis found.

American prosecutors and other officials have praised deferred prosecution deals and other types of money laundering settlements as effective tools for making sure big banks follow the law and stop serving criminals. When authorities announced Standard Chartered’s deferred-prosecution deal in 2012, an FBI official declared: “New York is a world financial capital and an international banking hub, and you have to play by the rules to conduct business here.”

ICIJ’s investigation shows that five of the banks that appear most often in the FinCEN Files — HSBC, JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered and Bank of New York Mellon — continued moving cash for suspect people and companies in the wake of deferred prosecution agreements and other big money laundering enforcement actions.

Four of those banks signed non-prosecution or deferred prosecution deals in the past 15 years relating to money laundering. The only bank of the five that hasn’t been the subject of a non- or deferred prosecution agreement is Deutsche Bank. Instead, it reached a $258 million civil settlement in 2015 in response to a probe by U.S. and New York banking regulators that found that the bank had moved billions of dollars on behalf of Iranian, Libyan, Syrian, Burmese and Sudanese financial institutions and other entities sanctioned by the U.S.

Bank of New York Mellon was among the first big banks to pay a large penalty to U.S. authorities for anti-money-laundering failures. In 2005, two years before its merger with Mellon Financial, Bank of New York paid $38 million dollars and signed a non-prosecution agreement after a federal probe concluded that it had allowed $7 billion in illicit Russian money to flow through its accounts.

Media reports said investigators believed that Mogilevich, the alleged Russian mafia “Boss of Bosses,” was behind some of the transactions.

Even as it’s avoided big money laundering enforcement actions in recent years, Bank of New York Mellon has continued doing business with suspect figures, the FinCEN Files show.

The leaked records show, for example, that Bank of New York Mellon moved more than $1.3 billion in transactions between 1997 and 2016 tied to Oleg Deripaska, a Russia billionaire and a longtime ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Since 2008, Deripaska has been the subject of allegations in media reports tying him to organized crime. When U.S. authorities announced sanctions against him in 2018, they said he had been previously been accused of threatening the lives of corporate rivals, bribing a Russian government official and ordering the murder of a businessman.

Deripaska denies laundering funds or committing financial crimes. In 2019 the Trump administration lifted sanctions on three companies linked to him. U.S. sanctions on Deripaska himself remain and he’s suing in an effort to upend them.

“BNY Mellon takes its role in protecting the integrity of the global financial system seriously, including filing Suspicious Activity Reports,” the bank said in a statement. “As a trusted member of the international banking community, we fully comply with all applicable laws and regulations, and assist authorities in the important work they do.”

Red flags

One striking pattern revealed by ICIJ’s analysis of the leaked records is the willingness of multiple banks to process transactions for the same risky clients.

Deripaska, the Russian oligarch, didn’t just have Bank of New York Mellon helping him out. The secret records reveal Deutsche Bank shuffled more than $11 billion in transactions between 2003 and 2017 for companies he controlled.

The records also indicate that Deutsche Bank and Standard Chartered helped Odebrecht SA — a Latin American construction firm behind what U.S. prosecutors called the largest foreign bribery case in history — move $677 million from 2010 from 2016. Deutsche Bank played a role in transactions involving more than $560 million of that amount, the records show.

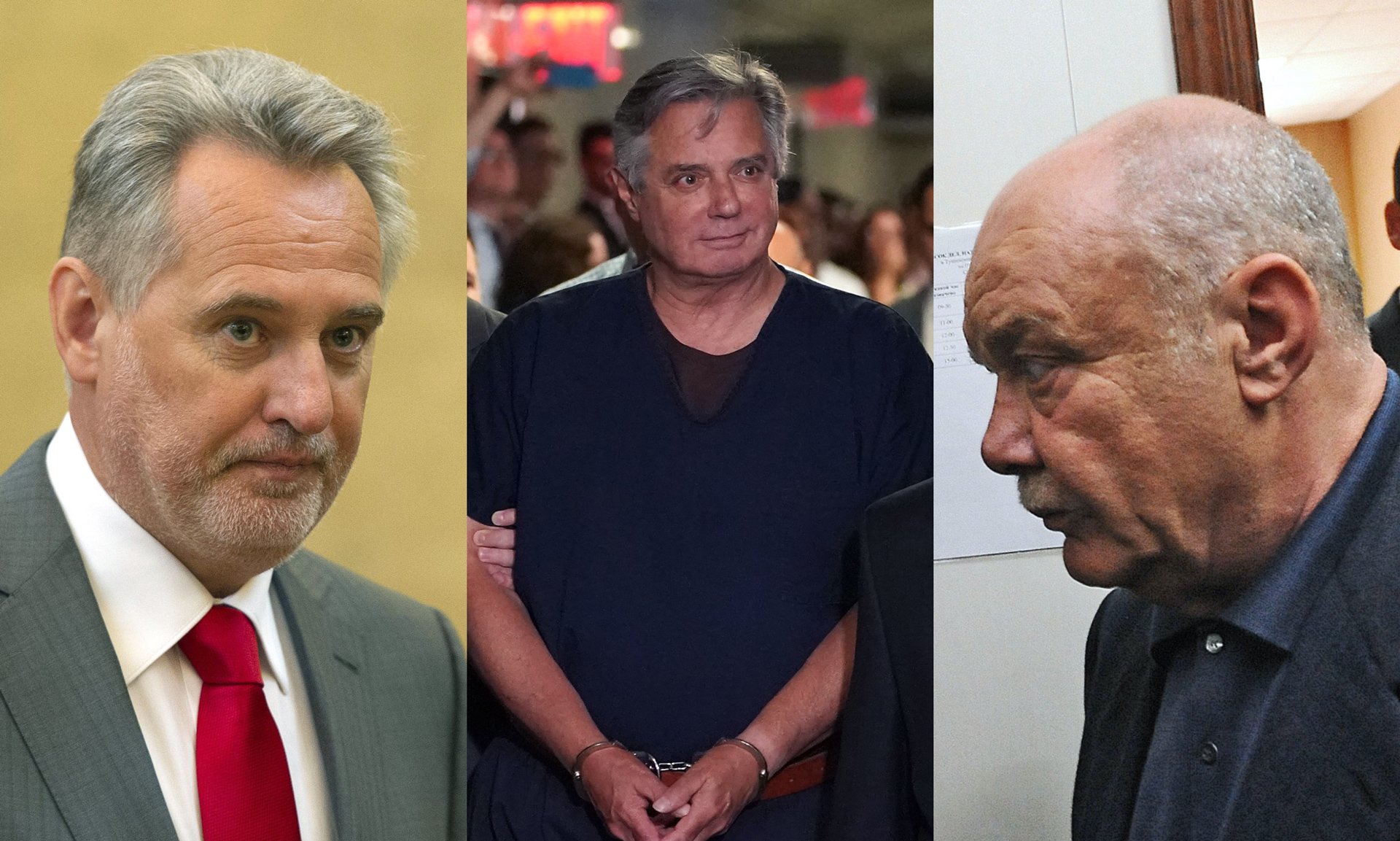

Then there’s Dmytro Firtash, a Ukrainian oligarch who is wanted on criminal charges in the U.S.

In 2014, American prosecutors unsealed an indictment accusing him of bribing officials in India in an effort to secure a mining deal. Since late 2019, U.S. news outlets have reported on claims that Firtash played a role in President Trump’s effort to dig up dirt in Ukraine on his 2020 reelection opponent, Joe Biden.

Firtash, who says he began his climb in business trading Ukrainian powdered milk for Uzbek cotton after the fall of the Soviet Union, lives in exile in a mansion in Vienna, protected so far from efforts to extradite him. His Art Nouveau villa has a home cinema and an infinity pool — a 2017 profile by Bloomberg Businessweek dubbed him “the Oligarch in the Gilded Cage.”

When it comes to banking, he and companies tied to him found open doors among many of the industry’s big institutions.

All five big banks in ICIJ’s analysis — JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered, HSBC and Bank of New York Mellon — handled transactions for companies controlled by Firtash, the FinCEN Files show. And the records indicate that all five approved transactions tied to Firtash in the time periods after U.S. authorities had forced the banks to pay fines and pledge to work harder to vet suspect clients.

The files show that among these banks, JPMorgan moved the most money for companies controlled by Firtash by far — shuffling hundreds of transactions totaling nearly $2 billion between 2003 and 2014.

JPMorgan and the other banks should have been aware of Firtash’s questionable history as far back as 2010, when a leaked U.S. diplomatic cable linked Firtash to Mogilevich.

Then in 2011, a lawsuit filed in Manhattan by former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko provided the banks even more of a heads up, even naming specific accounts at four of the banks that the suit alleged were being used by Firtash for money laundering.

The suit accused Firtash, Mogilevich and future Trump campaign manager Manafort of laundering illicit funds from Ukraine through banks and investment deals in the U.S.

The suit claimed accounts at the New York offices of JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered and Bank of New York Mellon were being used in money laundering operations shifting money stolen in Ukraine to the U.S. and then — after it had been cleaned — round-tripping it back to Ukraine.

Despite the allegations, these five banks continued to handle transactions involving companies controlled by Firtash, the FinCEN Files show.

The lawsuit was dismissed in 2013, in part because Tymoshenko and her lawyers weren’t able to provide enough specifics of the transactions involved in the alleged scheme.

Firtash has denied wrongdoing, telling Bloomberg Businessweek that he’s the victim of “a special machine of propaganda organized against me.” He told the magazine that Tymoshenko was “wrong in everything. She lies all the time. In order to money launder, you need to have dirty money to start with. I always had clean money.”

In a statement, an attorney for Firtash told ICIJ that Firtash “has never had any partnership or other commercial association with Semion Mogilevich.” The attorney said Firtash would not answer questions from ICIJ because its queries are “reliant on the unlawful and criminal disclosure” of suspicious activity reports.

Holding bankers accountable

Why haven’t seemingly big financial penalties done more to change banks’ behavior?

John Cassara, a financial crime expert who worked as a special agent assigned to FinCEN from 1996 to 2002, said that the size of the penalties paid by HSBC and other big banks may sound large but that they’re a tiny fraction of the banks’ profits. And the money isn’t paid by the bankers who should be held accountable, he said — it’s paid by shareholders.

BNP Paribas, France’s largest bank, received the biggest fine of all in 2014, when it was forced to pay $8.9 billion in the face of evidence that it helped shift billions of dollars through the U.S. financial system on behalf of Sudanese, Iranian and Cuban entities subject to American sanctions.

Unlike settlements with HSBC and others, this wasn’t a deferred prosecution. The bank agreed to accept a criminal conviction, and to force out 13 staffers.

But for the French bank, the priority in settlement negotiations was ensuring that its license to process dollar transactions in the U.S. wasn’t permanently taken away. Instead, U.S. regulators barred BNP Paribas from such activities for one year.

After the deal was announced, the bank’s share price rose 4%.

James S. Henry, a New York-based economist, attorney and author who has been investigating the world of dirty money since the 1970s, says American enforcement actions over the past two decades have had some impact on large banks’ behavior — at least compared to an earlier era when they operated with almost no restraints.

But he said it’s going to take “more prosecutorial will and international collaboration” to truly change the relationship between banks and illicit cash flows. That includes holding banks as institutions — as well as top bankers themselves — accountable.

“We have to put some senior executives who are in charge of this stuff at risk,” Henry said. “And that means fines and/or jail.”

Shark tank

It sounded like something out of a spy novel.

Deutsche Bank employees instructed clients from Iran and other hot spots to lace their payment messages with code words that would trigger special handling. One executive urged workers to employ “tricks and cunning” to avoid detection by American authorities.

These tricks of the trade were exposed in a November 2015 announcement by New York banking regulators. Deutsche Bank, state officials said, had been caught shifting nearly $11 billion between 1999 and 2006 on behalf of Iran, Syria and other countries under U.S. sanctions.

Under the $258 million settlement with the state and the Federal Reserve, Deutsche Bank agreed to reform its practices and fire employees involved in the sanctions-evasion operation.

In a statement, Deutsche Bank framed the deal as old news: “The conduct ceased several years ago, and since then we have terminated all business with parties from the countries involved.”

A month after the settlement was announced, the FinCEN Files show, Deutsche Bank was working behind the scenes to move money for a company linked to Ihor Kolomoisky — a Ukrainian billionaire who, U.S. prosecutors later alleged, was engaged in a massive laundering scheme that funnelled cash into the American heartland.

Kolomoisky has his own spy thriller mystique. U.S. prosecutors say he’s long been known for “ruthlessness and even violence” in business dealings, once hiring “armed goons” to take over the offices of a government-owned oil company. In an article in the Wall Street Journal, one associate recalled meeting with Kolomoisky and watching as the oligarch pressed a remote-control switch that dropped crayfish meat to the hungry sharks occupying his office aquarium.

The leaked records show Deutsche Bank moved $240 million from December 2015 to May 2016 for a shell company registered in the British Virgin Islands that, U.S. court filings claim, was controlled by Kolomoisky and a business partner.

A lawsuit filed last year in state court in Delaware alleges Kolomoisky used the shell company, Claresholm Marketing Ltd., to help pull off a “series of brazen fraudulent schemes” via PrivatBank, a Ukrainian institution that Kolomoisky and a partner controlled until the end of 2016. The new owners of the bank claim in the suit that Kolomoisky and his associates siphoned away billions of dollars from the bank through sham loans and then laundered the money through investments in the U.S.

This past July, New York regulators reached another money laundering settlement with Deutsche Bank. This time, the bank agreed to pay $150 million in penalties related to its dealings with convicted sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein as well as with two non-U.S. banks involved in money laundering scandals.

A month later, U.S. prosecutors filed civil forfeiture complaints in federal court in Florida that included allegations of thievery and money laundering against Kolomoisky similar to the claims in the Delaware lawsuit.

Prosecutors say much of the money allegedly stolen from PrivatBank between 2008 to 2016 ended up in investments in the U.S. — including commercial real estate in Texas and Ohio, steel plants in Kentucky, West Virginia and Michigan and a cellphone factory in Illinois.

Kolomoisky did not respond to questions from ICIJ. A lawyer for him said in August: “Mr. Kolomoisky emphatically denies the allegations in the complaints filed by the Department of Justice.”

In the state court case in Delaware, lawyers for Kolomoisky’s businesses said the suit fails to show violations of racketeering statutes or other laws. Kolomoisky has also filed a defamation action against PrivatBank in Ukraine, claiming the bank has falsely accused him of fraud and other wrongdoing.

Deutsche Bank declined to answer questions about its dealings with Kolomoisky, saying it was legally restricted from commenting on clients or transactions. The bank told ICIJ that it has acknowledged “past weaknesses” and “learnt from our mistakes.”

It said it has “systematically tackled” these issues.

“We are a different bank now,” it said.

—

Update, Sept. 21, 2020: This story was updated to add a comment from Standard Chartered Bank about a lawsuit filed against the bank by two ex-employees, and to add details about a related lawsuit.

Update, Dec. 22, 2020: This story has been updated to add a comment from Andriy Klyuyev.