To celebrate the third anniversary of the Panama Papers – and to mark World Press Freedom Day – we’re speaking with reporters from around the world about the investigation each week.

For our final installment, we spoke with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ member Lyas Hallas. Lyas was the sole reporter to work on the Panama Papers investigation in Algeria, Africa’s largest country.

Like many of our partners, Lyas’ work is still having an impact. Most recently, authorities arrested some wealthy Algerians named in the Panama Papers and street protesters calling for the president’s resignation and an end to corruption waved banners that featured the businessmen’s faces.

What was the biggest impact in Algeria after the Panama Papers’ revelations?

There was an immediate debate about assets held by Algerians overseas. The reaction shook the leaders of our country who had planned their retirements abroad. The Panama Papers also hit hard the businessmen who consort with politicians and who enjoy tax and banking advantages at home and yet who hide their money offshore. The revelations politically weakened ministers who were at the height of their power and others who were on the cusp of bouncing back.

One example was the then Industry Minister Abdesselam Bouchouareb, who was tipped to be the next prime minister before that became awkward due to the global firestorm in the wake of the investigation

Maybe my work contributed to bringing attention to the pillage of the country’s resources. – Lyas Hallas

What was your favorite moment of the Panama Papers investigation? What surprised you the most?

Favorite moment? A huge ‘catch’ when just one minute after I opened the Panama Papers database for the first time, I found Rym Sellal, the daughter of the then prime minister, Abdelmalek Sellal. It was very motivating.

I also didn’t expect to find the owner of an offshore company linked to the entourage of former energy minister Chakib Khelil who is at the heart of the Sonatrach corruption scandal, our state-owned oil and gas company.

Italy and Algeria had opened court cases and Italian judges had identified this offshore company as one of 17 used to launder $216.92 million (€194 million) in bribes. Yet neither Italy nor Algeria had called on Khelil as a witness. Ditto for the son of the former Sonatrach CEO who received six years in prison for corruption.

What also stuck with me about the Panama Papers is the interest of Algerians in this kind of story. In two years, I published a dozen stories and there was a buzz every time.

What were the most significant reactions to your investigations?

The general public reacted well, which was satisfying… In Switzerland, a criminal court dismissed a case brought by an Algerian businessman based, in part, on my Panama Papers reporting.

I had to resign from the newspaper where I worked in order to get my investigation published. I had a story on the Minister of Industry at the time, Abdeslam Bouchouareb.

Bouchouareb put a bit of pressure on the editor – I don’t know what they said. Five days before the agreed publication date with ICIJ, I had to find another newspaper to publish my story… I found one easily, which was good.

I was harassed online by various digital players in the pay of government officials.

Some people said I was dancing to the tune of foreigners and others accused me of faking documents. Khelil wrote on Facebook, without naming me directly, that I was a “Zionist agent.” Obviously, I didn’t react to this kind of nonsense, which was mostly anonymous.

Some people even called me an “agent of Rebrab” [editor’s note: Issad Rebrab, Algeria’s richest man]. I had worked for 11 months in a newspaper where he is the majority shareholder and from which I resigned to publish my Panama Papers story. Yet Rebrab tried to sue me in France because of the Panama Papers.

For someone who has not followed anything, what has happened in Algeria now?

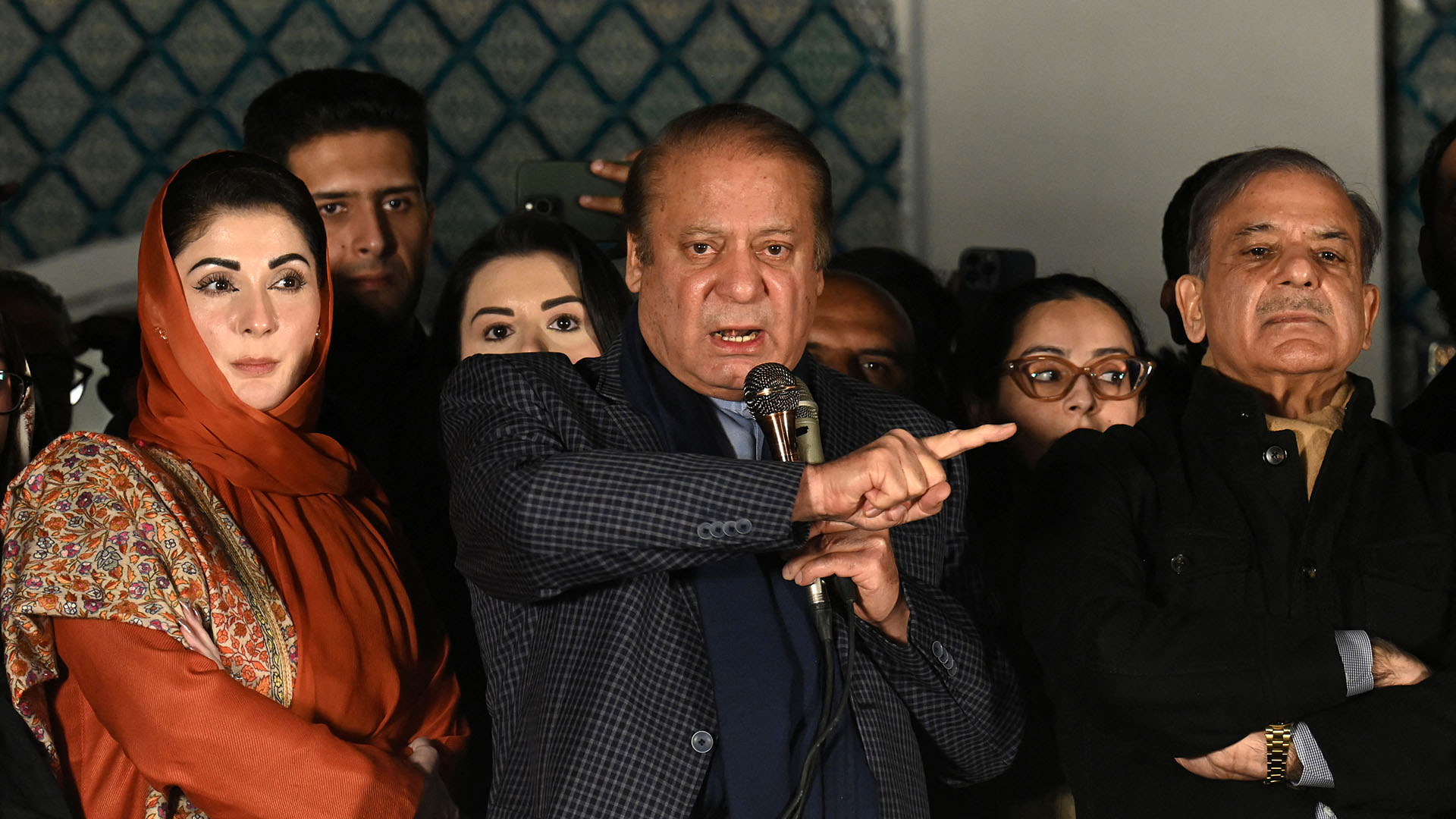

President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s desire to seek a fifth term sparked massive demonstrations on February 22 that forced him to resign. Algerians have long lived through his power grab as a great collective humiliation. Bouteflika did leave, but the system that he built — even if it’s weakened — is still in place.

Every Friday during the protests, millions of people rallied in unity around the theme “Get them all out!” The term “all” referred to those widely-despised figures from the Bouteflika era who, in the eyes of the demonstrators, embodied mediocrity, injustice and corruption.

What’s the connection between your Panama Papers investigations and recent events?

It’s not my job to spark protests. Maybe my work contributed to bringing attention to the pillage of the country’s resources and to the lack of some people’s “tax patriotism.” Or maybe it accentuated the feeling of injustice among many Algerians given the impunity of some people I wrote about.

During the recent protests, one of the main slogans was “You have devoured the country, band of looters!” Some protest banners included photos of politicians and businessmen I exposed.

In response to the demonstrations, authorities jailed some of these businessmen, including Issab Rebrab, in order to calm protestors and temper the country’s anger. A few days ago, the Supreme Court reopened a case involving Khelil. They are not being investigated for what I wrote about, but for similar practices to the things I uncovered.

Can you give us a summary of your investigations around these recently arrested men?

Businessman Ali Haddad, and as I mentioned earlier Issad Rebrab, have been arrested.

My investigation of Haddad revealed the illicit transfer of foreign currency through a complex arrangement involving foreign partners in the group of companies that carries out infrastructure projects in Algeria. Anti-corruption investigations against Haddad have not yet been concluded, but he was arrested at the borders with Tunisia while trying to flee.

As for Issad Rebrab, he was detained on charges of “misrepresentation of illicit transfers of capital from and to foreign countries, overcharging of imported equipment and importation of second-hand equipment while he had benefited from customs, tax and banking benefits”. My investigation questioned his background and the origin of his fortune. Policy makers have always made it easy for businessmen close to them to access credit, import licenses and government contracts, while guaranteeing them impunity since for business in Algeria, political support is needed.

The Supreme Court has reopened the case of Chakib Khelil, who has fled the country. Khelil is accused of bribery in a case involving contracts awarded by the state-owned oil company. My investigation revealed that his wife and his son were beneficiaries of offshore companies linked to a money laundering machine worth $220 million (€197 million) in commissions.

You are a veteran of journalism in Algeria. In what state was investigative journalism in Algeria before these demonstrations?

Investigative journalism in Algeria is fragile. It’s difficult to access information and Algerian media remains fundamentally based on opinion.

Even if Algerian media has some freedom in what it says, it doesn’t invest enough in going after real information. It’s subject to the government’s agenda and corporations’ marketing strategies. I would even say that it’s in a pretty sick state because it hasn’t evolved independently of the political forces now being protested against.

Algerian media didn’t develop an economic model based on its relationship with the audience that would have allowed financial independence. Advertising revenue has made the media dependent on advertisers and policymakers.

In short, much of the press is completely discredited. Especially given that the media itself was not untouched by corruption.

Algerians today are demanding a new kind of information and the current media are having a hard time satisfying this demand. Of course, there are small islands of resistance that try to offer quality information. But, it’s necessary to completely rebuild the system.

What is your hope for Algerian journalism after these protests and regime change?

I remain optimistic. The entire community of Algerian journalists is aware of the stakes. I hope that we will have the collective intelligence to set new rules of the game; rules that will establish healthy competition and favor new editorial practices to properly inform Algerians.

I don’t dismiss the value of Algeria’s press in the past, which emerged from struggles that saw journalists sacrifice their lives from generation to generation to be able to freely exercise their profession, especially in the 1990s, a decade in which terrorism had wreaked havoc on Algeria. We lost a hundred journalists and others who were murdered because they were journalists.

But the media system as a whole requires a re-foundation to clarify the ground rules. The opacity that Algeria’s media has evolved into exposes it to arbitrariness.