Muslims worldwide have been flocking to a mobile file-sharing application called Zapya, developed by a Beijing-based startup that encourages users to download the Quran and share religious teachings with loved ones.

The app, developed by DewMobile Inc., allows smartphone users to send videos, photos and other files directly from one smartphone to another without being connected to the web, making it popular in areas where internet service is poor or nonexistent.

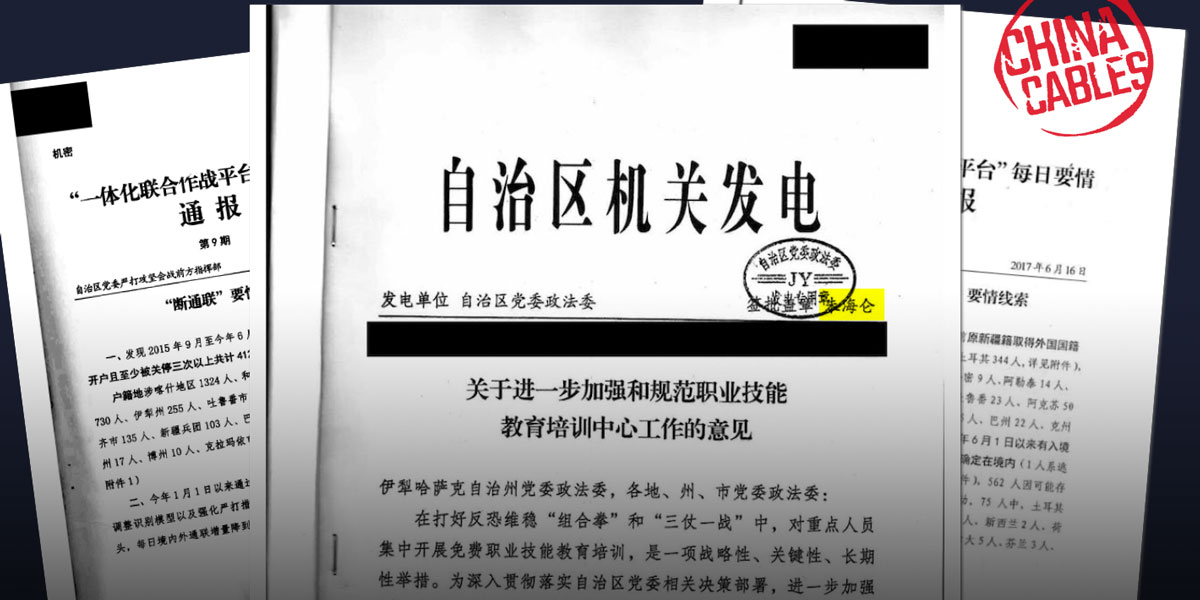

A leak of highly classified Chinese government documents, the China Cables, now reveal that since at least July 2016, Chinese authorities have been targeting users of the Zapya app, known in Chinese as Kuai Ya (fast tooth), as part of their crackdown against the Muslim Uighur population. Officials have closely monitored the app on some Uighurs’ phones and flagged its users for further investigation, according to leaked documents obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and shared with 17 media partners.

Responding to questions about the camps and surveillance program from ICIJ media partner the Guardian, the Chinese government called the leaked documents “pure fabrication and fake news.” In a statement, the press office of its UK embassy said: “There are no so-called “detention camps” in Xinjiang. Vocational education and training centres have been established for the prevention of terrorism.”

One document included in the China Cables instructs government officials to locate and arrest people described as “violent terrorists and extremist elements who used the ‘Kuai Ya’ software to spread audio and video with violent terroristic characteristics.”

The material doesn’t explain how the government obtains user data from Zapya — the only app mentioned in the documents by name. The documents provide no indication that the company cooperated with Chinese authorities.

Uighur refugees say police often seize phones and look through them.

Zumrat Dawut, a Uighur woman who said she spent three months in a detention camp, told ICIJ that police would search for Zapya, among other apps, in Uighurs’ phones. “If anyone had downloaded some kind of religious content and religious words from the Quran or any word like ‘Allah,’” Dawut said through a translator, “if police found something like that in their mobile phone, they would be detained.”

DewMobile representatives didn’t respond to ICIJ’s repeated requests for comment via email and phone.

The leaked documents make public for the first time the Chinese Communist Party’s operational plans for the largest civilian mass internment of an ethnic-religious minority since World War II. The operation is being carried out in Xinjiang, a remote northwestern province the party considers a “key battlefield in the fight against terrorism and [religious] extremism in China.”

Among the documents are bulletins issued by Xinjiang’s Communist Party Committee. They outline the central role of surveillance technology in what experts fear is a chilling laboratory for authoritarian tactics ripe for export worldwide.

“The implications are dramatic,” said Adrian Zenz, an expert on Xinjiang and China’s policies. “With these digital information systems, [the Chinese government] believes it can really gauge what a person really does, what a person really believes. What are they doing on a regular basis? How are they really behaving? What are they saying when nobody listens?”

Since spring 2017, Chinese authorities have detained more than a million Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in huge internment camps across Xinjiang, which is home to nearly 11 million Uighurs.

The mass-detention operation is part of a larger push by Beijing to suppress political dissent and religious expression, particularly among minorities in a nation dominated by Han Chinese. The goal, experts say, is to reinforce Communist Party doctrine, a drive that has accelerated in recent years. After initially denying the camps’ existence, the Chinese government now claims that they are “vocational education and training centers” and are needed to help fight “terrorism and religious extremism.”

But Western governments, nongovernmental organizations and Uighur refugees condemn the policy, and one U.S. commission calls the state of affairs in Xinjiang “one of the world’s worst human rights situations.”

Predictive Policing

Among the Chinese government’s most sophisticated tools for population control is a mass-surveillance and “predictive policing” program known as the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, or IJOP. It aggregates data about individuals – often without their knowledge – and flags for authorities those it deems potentially threatening or otherwise “suspicious,” according to a recent Human Rights Watch report.

According to the New York-based human rights group, the Chinese government is using IJOP to compile a massive database of intimate personal information from a range of sources. Those sources include national identification documents, Xinjiang’s countless checkpoints, closed-circuit cameras with facial recognition, spyware that the police force Uighurs to install on their phones, “Wi-Fi sniffers,” which collect identifying information on smartphones and computers, and package delivery, according to the report. The system also has a mobile app that police and other officials use to run background checks and communicate with the IJOP in real time.

Human Rights Watch first reported on the platform in early 2018. Maya Wang, senior China researcher with the human rights group, said that whenever someone in Xinjiang buys a car or, in fact, anything requiring an official license, their personal data is uploaded to the platform’s database. Its purpose, she said, is to filter “Xinjiang residents through the sieve of technology.”

The leaked documents include four “IJOP Bulletins.” The leak represents a definitive confirmation, based on the Chinese government’s own documents, of the program’s existence. The bulletins were issued June 16-29, 2017 and signed by Zhu Hailun, then deputy secretary of Xinjiang’s Communist Party and the region’s top security official.

Before Zapya, Chinese authorities flagged other mobile apps, including WeChat, developed by Chinese conglomerate Tencent Holdings, as potential threats to political stability. WeChat, a Chinese messaging and social media app, became popular as a way to create virtual communities and discussion groups about a variety of topics, including religion. Uighurs were sentenced to prison for using WeChat to teach about Islam, according to media reports.

Tencent didn’t respond to ICIJ’s requests for comment.

Human rights experts say that the data collected through apps like Zapya and WeChat is a key component of China’s multibillion-dollar mass surveillance and control operation. An investigation this past summer by Süddeutsche Zeitung, The Guardian and The New York Times found that Chinese border police had seized the phones of foreign tourists visiting Xinjiang and secretly installed a surveillance app on the devices.

According to one of the leaked IJOP bulletins, as of June 2017, more than 1.8 million Uighurs in Xinjiang were using Zapya. The number included nearly 4,000 of what the document calls “unauthorized imams.”

The document instructs officials to use data stored by IJOP to investigate Uighurs “one by one,” as thoroughly as possible, to find what it describes as terrorism suspects. “If it is not possible at the moment to eliminate suspicion,” it says, “it is necessary to put [the suspect] in concentrated training and further screen and review.”

Reports that emerged later in the summer of 2017 appear to confirm that authorities in Xinjiang had begun to implement the IJOP guidelines. A few weeks after the IJOP document mentioning Zapya was disseminated, for instance, a few news sites and individuals reported that authorities were arresting and jailing Uighurs found to have downloaded Zapya onto their devices. The Uighurs were accused of using the app to distribute extremist content.

ICIJ’s partner Le Monde reported that a computer scientist from Xinjiang’s regional capital, Urumqi, had been sent to a detention center twice, each time for 30 days, for downloading the Zapya app.

Last year, the website Bitter Winter, run by an Italian nonprofit group that advocates religious freedom, published an undated Chinese government document that flagged the use of Zapya to possess and disseminate religious material as a potential crime, akin to wearing a burqa or a long beard and other behavior labeled by the government as potentially dangerous.

‘Building Mistrust’

DewMobile’s path to market was fairly standard for tech startups. Its founders launched Zapya with financing from InnoSpring Silicon Valley, a Palo Alto, Calif., unit of the Shanghai-based InnoSpring, a venture capital firm. InnoSpring raises money from Chinese and American investors and provides seed funding and management support to startups in China and the United States. Founding partners in the California fund include Silicon Valley Bank, based in Santa Clara, Calif., and Tsinghua University, in Beijing, which counts among its alumni Chinese President Xi Jinping and his predecessor, Hu Jintao.

Since its launch in 2012, more than 450 million people have downloaded Zapya, according to DewMobile.

But it has also encountered problems. In mid-2017, a group of California cybersecurity analysts reported that hackers had exploited flaws in Zapya, WeChat, and other apps to infiltrate users’ phones and steal private information.

The internet provided a space for religious and cultural expression, but then later it became evidence of their ‘religious extremism.’

– Darren Byler

The perpetrators of the hack are unknown but Peter Hannay, a malware researcher at Edith Cowan University, said that “we’re looking at something produced by a well-resourced organization.” In an interview with ICIJ’s partners at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Hannay said one thing is clear: “The purpose is surveillance.”

Tencent and DewMobile didn’t respond to ICIJ’s questions about the alleged hacks. On their websites, both companies say they use a variety of tools to protect user information but cannot guarantee full protection.

Users initially thought of apps such as Zapya as liberating, not realizing that they were leaving a digital trail that later could be used against them, said Darren Byler, an anthropologist at the University of Washington who studies the Uighurs. “So the internet provided a space for religious and cultural expression,” Byler told ICIJ, “but then later it became evidence of their ‘religious extremism’ or ‘cultural separatism.’”

Uighurs inside and outside China now live with the knowledge that their communications are constantly monitored by the authorities. Uighurs overseas who phone home often find conversations turning awkward before realizing that their relatives in Xinjiang are likely not alone but seated next to a police officer listening in.

On online bulletin boards, participants advise Uighurs against installing Zapya altogether, to avoid arousing government suspicion.

Uighurs interviewed by ICIJ said that avoiding surveillance is often impossible.

Ferkat Jawdat, a Uighur refugee and software engineer living in the United States, said calls to Xinjiang on WeChat sometimes require him to click through a pop-up message warning that the call is being “compromised.”

Fearing that authorities could use their conversations against them, Uighurs abroad have stopped communicating with loved ones in Xinjiang altogether, Jawdat told ICIJ.

The surveillance “is building mistrust between all the members of the Uighur community,” Jawdat said. “It is causing mental anguish and destroying families.”