Allowing the owners of shell companies to hide their identities from United States authorities constitutes a “significant loophole” in the country’s ability to tackle money laundering and illicit financing, a senior FBI official told a powerful Washington committee this week.

This cloak of legal anonymity facilitated by state laws is frustrating law enforcement efforts to track up to $2 trillion in annual proceeds from international crime, Acting Deputy Assistant Director, FBI Criminal Investigative Division, Steven M. D’Antuono warned members of the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee on May 21.

D’Antuono said: “The FBI has countless investigations, spanning criminal and national security threats, in which illicit actors, operating both domestically and internationally, use shell and front companies to conceal their nefarious activities and true identities. The strategic use of these entities makes investigations exponentially more difficult and laborious.

“The ability to easily identify the beneficial owners of these shell companies would allow the FBI and other law enforcement agencies to quickly and efficiently mitigate the threats posed by the illicit movement of the succeeding funds.”

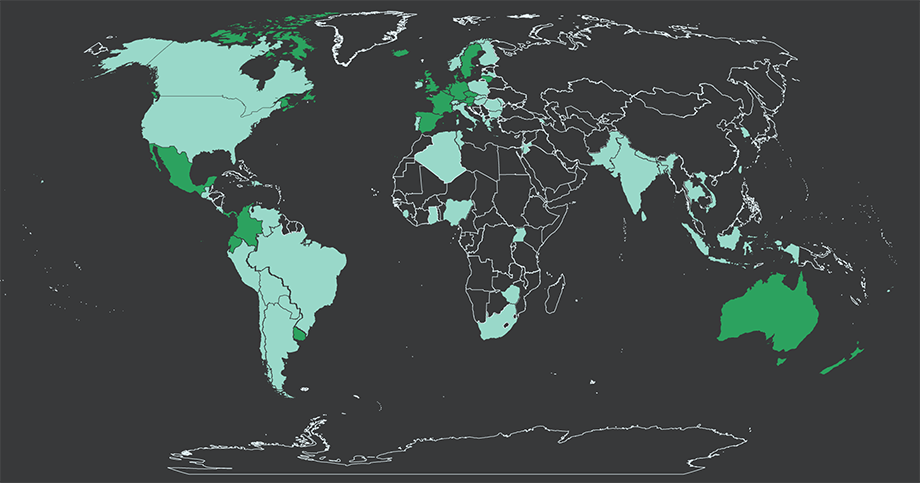

The FBI and other law enforcement agencies want to bring U.S. law into line with the more stringent regulations adopted by the European Union in recent years which, among other provisions, mandate member states to compile centralized registers on beneficial ownership and to make these widely – even publicly – accessible.

The EU reforms were prompted by the revelations contained in the Panama Papers, the ground-breaking 2016 investigation produced by The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, in conjunction with more than 100 media partners.

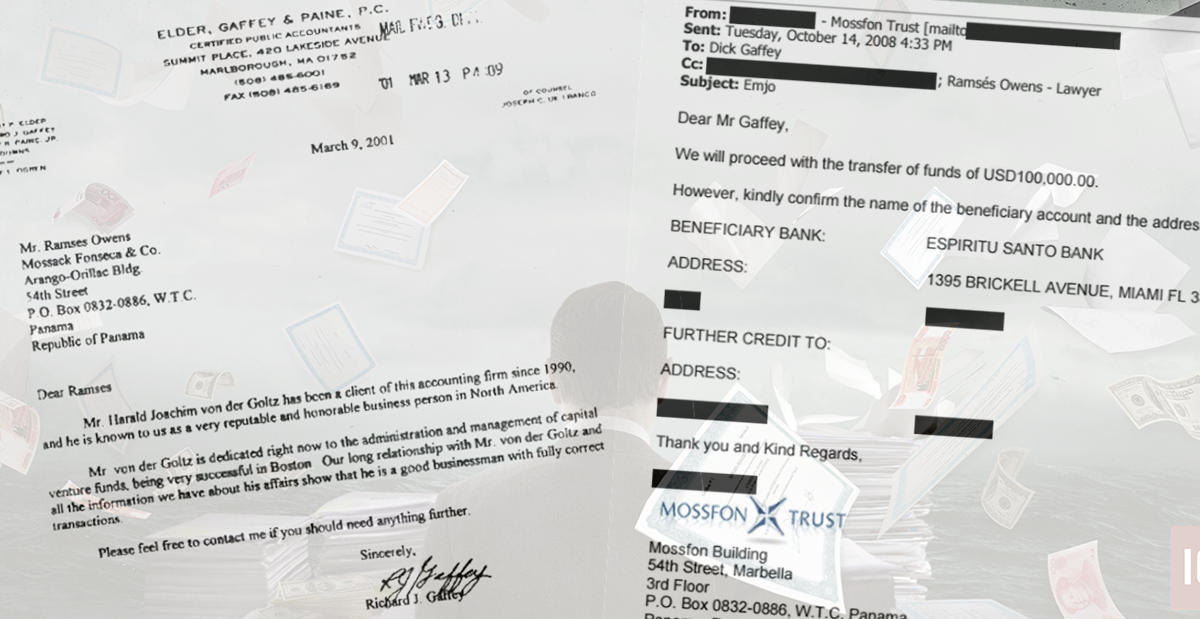

The Panama Papers were based on information gathered from 11.5 million leaked documents from the now-defunct Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca. They exposed secretive offshore holdings, many of them held by U.S. citizens or individuals conducting business in the U.S.

Mossack Fonseca’s U.S.-based subsidiaries established thousands of U.S.-based shell companies in several states but according to D’Antuono, regulators were effectively stymied in their subsequent investigations because of the lack of ownership information.

When investigators began investigating the Mossack Fonseca companies in the wake of the Panama Papers, they quickly discovered the limitation of incorporation information in U.S. states.

“All that the investigator could learn was that the agent was ‘MF Nevada’ or the like,” D’Antuono told the committee. “This, of course, made investigating the shell entities extremely time-consuming, inefficient and difficult.”

At present, U.S. companies are incorporated at state rather than national level. None of these require disclosure of the ultimate owner or beneficiary at registration and this is compounded by current federal laws which, other than in very exceptional circumstances, do not require the identification of beneficial owners when opening an account with a financial institution.

D’Antuono told the committee that the “near complete lack of transparency” in the U.S. allows international crime gangs and corrupt individuals to move assets derived from criminal activities such as drug dealing, political corruption, tax evasion, human trafficking and child prostitution.

Moreover, as a result of the tighter controls in Europe, the U.S. has become a magnet for dirty money.

“This hearing is an important step towards developing the laws needed to effectively combat illicit financing through the use of anonymous vehicles,” he said.