The publication of the names and offshore ties of Colombia’s elite through the 2016 Panama Papers investigation has helped double taxes collected by authorities, a new study has found.

After publication of the Panama Papers, Colombian taxpayers disclosed 15 times more assets held abroad than had been previously reported, according to University of California (Berkeley) researcher Juliana Londoño Vélez, who matched the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ Offshore Leaks data with detailed tax filings of more than 1,200 Colombians.

The publication of the Panama Papers, and a voluntary disclosure program aimed at encouraging taxpayers to report hidden assets, also made Colombian citizens more forthcoming about assets. Londoño-Vélez found that the Panama Papers “induced a ninefold increase” (an 830 percent spike) in what taxpayers disclosed to the Colombian tax agency about all their wealth halfway through the voluntary disclosure program that began in 2015.

The study was also made possible, in part, thanks to Colombia’s unique taxation records and a string of laws that influenced Colombian’s offshore behavior.

Under the tax code, Colombians must report information about the wealth they own to authorities every year. Second, data from taxpayer filings following a 2002 “wealth tax” imposed on Colombians who own wealth above certain thresholds allowed researchers to follow the money and see how Colombians changed what and how they filed, in some cases to avoid the wealth tax. Finally, Colombia introduced a voluntary disclosure scheme in 2015 that helped researchers track taxpayers who disclosed assets to the tax office from offshore shelters in exchange for Colombia waiving past tax bills.

In the middle of those changes, Londoño-Vélez told ICIJ, the Panama Papers erupted. It provided a rare opportunity to see how those named in the Panama Papers would react.

“For me as a researcher, it’s interesting, and it’s unanticipated,” said Londoño-Vélez, who was given access to Colombian tax records by the tax agency. “We can use its timing to interpret any effect that we see as causal. ‘What is the effect of the Panama Papers on disclosures?’”

Compared to previous studies that examined the impact of policies and initiatives on the repatriation of money from offshore, the new study “shows massive results — much higher than I would have expected — and thus is very significant,” said Rita de la Feria, chair in tax law at the University of Leeds who was not involved in the research.

“Of course the paper is geographically selective — it only looks at Colombian data — and circumstances will differ from country to country, but I think it is fair to infer that this shows leaks can have a massive impact on tax compliance, through deterrence and fear of being detected,” de la Feria said.

In April 2016, ICIJ and more than 370 journalists from 76 countries published the first stories as part of the Panama Papers investigation.

ICIJ partnered with Colombian news organization Connectas, which reported on corporate executives, ministers and government officials, including the country’s former finance minister, who held money offshore.

In May 2016, ICIJ published tens of thousands of names of offshore companies, individuals and addresses from around the world as part of its Offshore Leaks database.

Colombian authorities, like other tax and law enforcement agencies, scoured the database for the names of citizens. Colombia’s tax agency, known by the acronym DIAN, started to contact almost 2,000 Colombians whose names appeared. DIAN official Javier Avila-Mahecha is one of the study’s co-authors.

Londoño-Vélez, who has worked on tax and political economy for years, also got to work.

“Literally, all of this was me going online and downloading whatever I could,” Londoño-Vélez said about her research. “There’s no fancy thing happening here.”

“What I’m doing is comparing people that are named in Panama Papers and those who are not and then the likelihood that they disclose hidden wealth before and after the leak,” Londoño-Vélez said.

Colombia has long struggled to stop its citizens, multinationals and political leaders from piping money offshore. Panama, which split from Colombia in 1903 and is home to the law firm whose files made up the Panama Papers, has long been a favorite offshore haven.

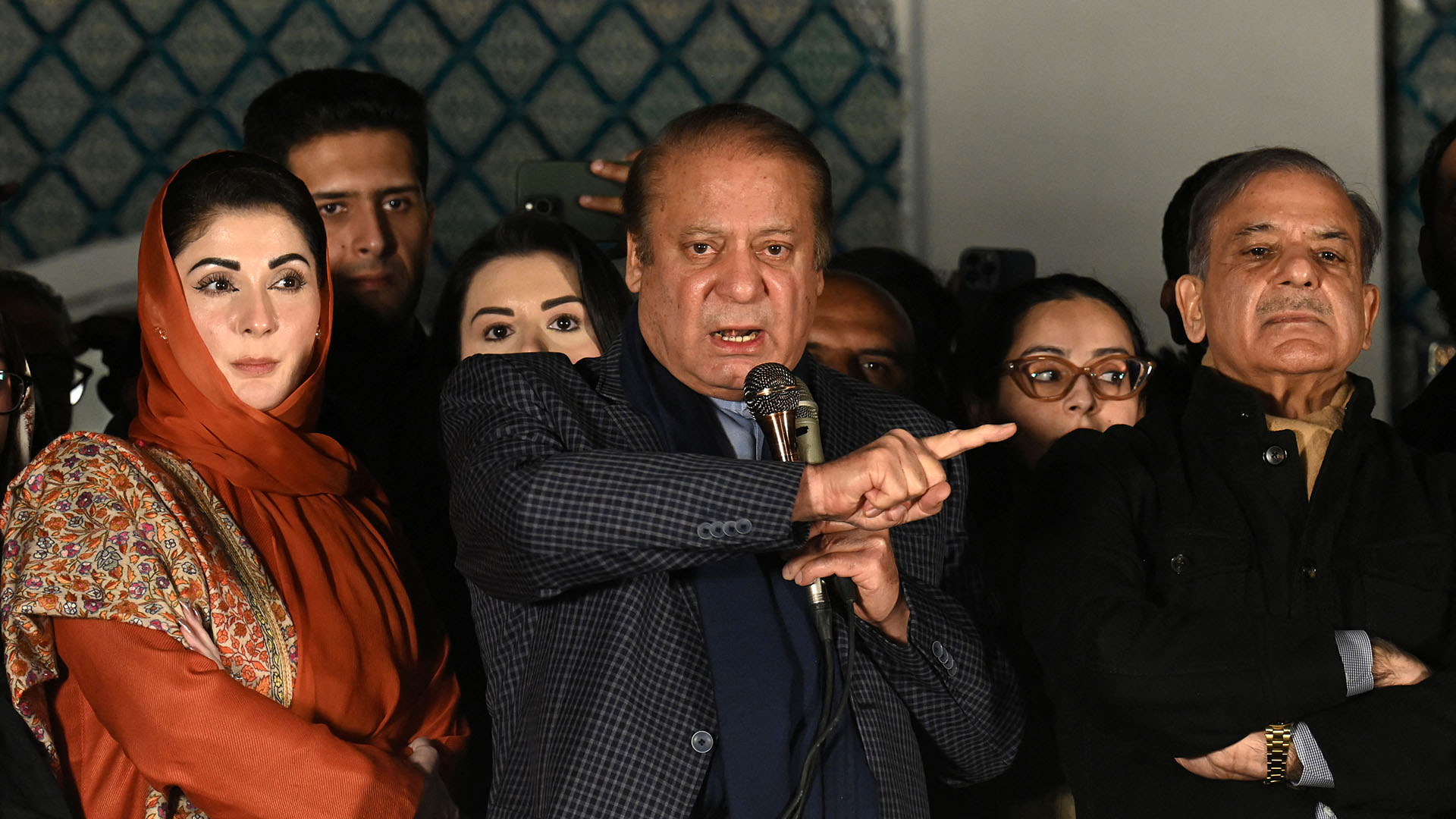

Colombia is now one of the most unequal countries on earth, second only to the U.S. in the skewed distribution of wealth. Colombia’s one percent – many of whom who use offshore vehicles and are older, white males –- own 40.64 percent of the country’s wealth, according to the study.

Partly in response to rising inequality and partly to help finance the country’s fight against drug trafficking and guerilla warfare, Colombia introduced a levy on taxable net worth in 2002 known as a “wealth tax.” Colombians fled offshore, and the use of offshore vehicles grew tenfold, the study found.

Later, Colombia introduced a voluntary tax disclosure program to lure its wealthy citizens’ billions back home. The Panama Papers broke halfway through the program’s lifecycle.

The official response was immediate. In May 2016, Panama agreed to share tax information with Colombia, a move that the tax haven had resisted for years. In December, Colombia made tax evasion a crime punishable by up to nine years in jail.

Londoño-Vélez said her study of how Colombia’s elite responded to the Panama Papers helps show how taxpayers flee offshore when faced with wealth taxes but respond to incentives to repatriate the money.

“I absolutely don’t think this one single program resolves the issue of offshore tax evasion in a country like Colombia,” said Londoño-Vélez. “But when you craft these programs carefully, voluntary disclosure programs can actually benefit everyone involved.”

“It is undoubtedly true that the leaks have lead to actual legal, policy or enforcement change,” said de la Feria. “Overall, it is hard to deny the public value of the leaks, and of the work of those reporting on the leaks.”