Immigrant detention centers in the United States are locking detainees with COVID-19 in solitary confinement cells for days or weeks at a time, with little opportunity for medical treatment, according to detainees and immigrant advocates.

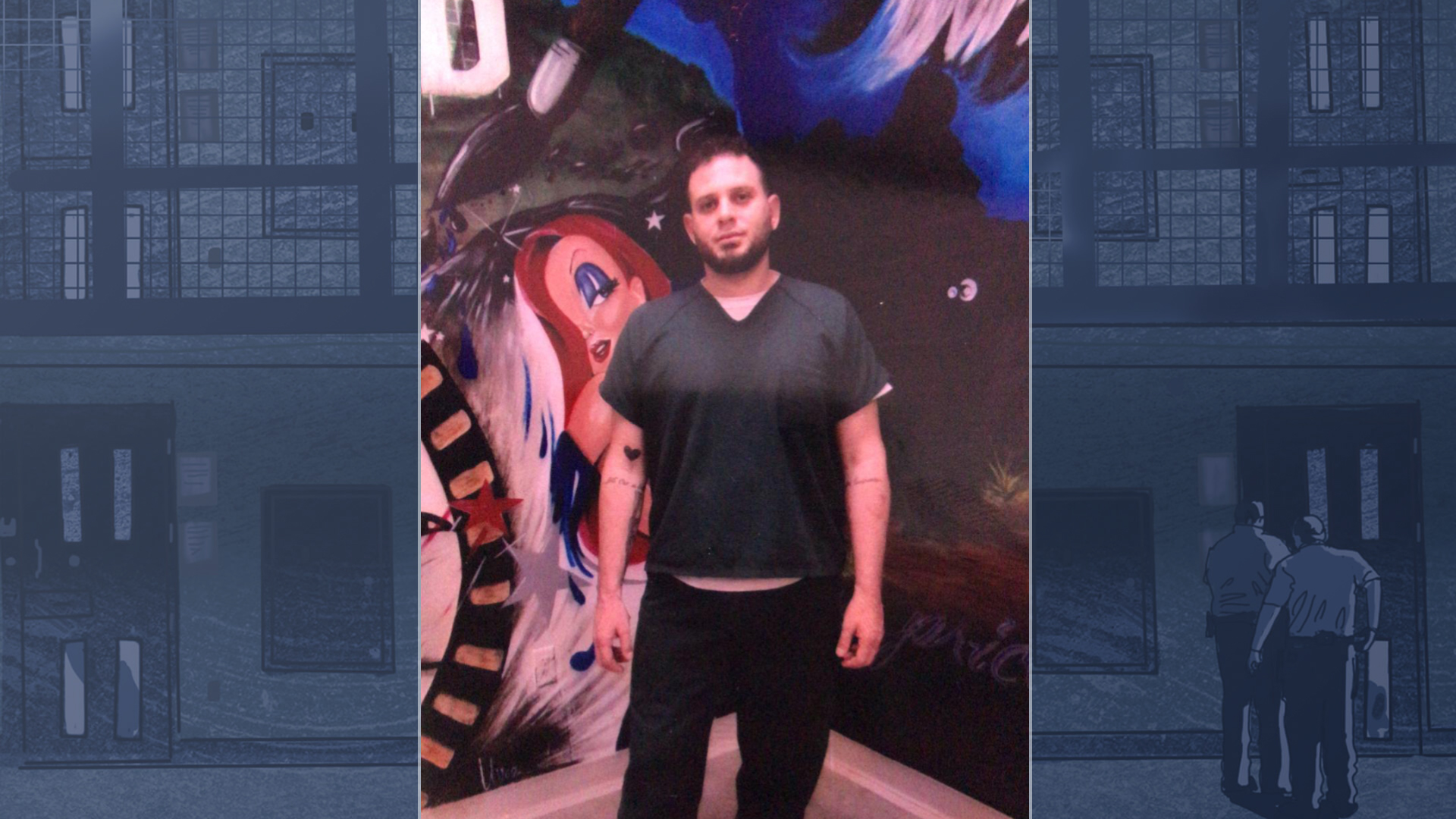

“In the end, what they did was psychologically torture me,” said Carlos Hernandez Corbacho, who said he spent more than a week in isolation cells at Arizona’s La Palma Correctional Center in June after showing symptoms of COVID-19. “That’s how I felt — like they were punishing me for getting sick.”

Quarantining people believed to have the coronavirus is crucial to slowing its spread. But solitary confinement cells that hold people detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, known as ICE, are a far cry from a hospital bed or a hotel room: cells are claustrophobic, sparsely furnished, and those confined are allowed limited social interaction. A stay can cause lasting trauma and trigger suicidal impulses.

Placing COVID-19 patients in solitary confinement, experts say, is inhumane and jeopardizes the overall population by deterring detainees from reporting symptoms.

“Resorting to solitary confinement to treat physically ill immigration detainees demonstrates ICE’s appalling inability to provide humane and truly civil detention,” said Ellen Gallagher, who works for the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of the Inspector General. Gallagher has been an outspoken critic of ICE’s use of solitary confinement, which she calls “barbaric.”

The United Nations special rapporteur on torture has said that solitary confinement should be banned except in “very exceptional circumstances.” In 2019, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ Solitary Voices investigation found that ICE routinely isolates detainees that it sees as difficult to manage, including the sick, disabled and mentally ill, for extended periods of time in solitary confinement cells.

In an emailed statement, ICE said that its quarantine practices are not a punitive measure and are conducted in accordance with the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control guidelines. “Detainees who test positive for COVID-19 receive appropriate medical care to manage the disease,” ICE spokesperson Danielle Bennett told ICIJ in a statement.

ICE said that while it does medically isolate detainees, the experience is substantially different than punitive forms of solitary confinement. Quarantined detainees have access to recreation, telephone calls and libraries — subject to “restricted movement protocols” necessary to stop the spread of COVID-19, Bennett said. They can also communicate with lawyers and courts.

At any given time ICE holds tens of thousands of detainees awaiting immigration proceedings or deportation — processes that have slowed since the outbreak of the pandemic — at facilities dotted across the U.S. Conditions are similar to those in prisons: detainees live in close quarters and find it impossible to socially distance.

In recent months, ICE detention centers have seen surging coronavirus case numbers, with some facilities reporting exponential outbreaks. As of mid-August, nearly 5,000 detainees had tested positive for the coronavirus and ICE says five had died, although immigration advocates say this is an undercount. Activists and detainees around the country have pressed ICE to improve facility sanitation and to release vulnerable detainees.

ICIJ spoke with three current or former detainees directly — all held at La Palma — and reviewed detailed case notes provided by advocates and detainees describing an additional six instances. Each said they were put in solitary confinement after they were exposed to someone who had contracted the virus, after showing symptoms, or after testing positive.

CDC guidelines say that medical isolation should be “operationally distinct” from punitive solitary confinement, “both in name and in practice.” But in court documents and in interviews, detainees said their experience was effectively the same. They were locked alone in small cells and received little to no medical aid, they said.

Freedom For Immigrants, an advocacy group, has received more than a dozen reports of ICE detention centers in California, Louisiana, Texas, Alabama, Colorado and Arizona placing detainees who were suspected to have coronavirus into solitary confinement cells, including those typically reserved for segregating violent detainees from the general population.

In May, Choung Woong Ahn, who according to ICE had a history of mental illness and suicide attempts, hanged himself while quarantined in a solitary cell at the Mesa Verde ICE Processing Facility in California. The 74-year-old was undergoing a 14-day isolation period after returning from a stay at a hospital.

Another detainee, Oscar Perez Aguirre at Colorado’s Aurora Contract Detention Facility, said he was hospitalized for COVID-19 symptoms, and returned to the facility so weak he couldn’t stand. He was put in a cold and dirty solitary confinement cell for more than two weeks, according to court documents.

In June, officials at Arizona’s Eloy Detention Center put at least 45 men in solitary confinement after they tested positive for COVID-19, Mother Jones reported.

At California’s Adelanto ICE Processing Center, and in Louisiana’s Pine Prairie Processing Center, detainees medically isolated in solitary cells reported being denied opportunities to shower and receive medical attention, according to Freedom for Immigrants.

Detainees at Adelanto and Alabama’s Etowah County Detention Center said they were reluctant to seek medical care due to fears of being placed in solitary confinement, the advocacy group reported.

“As the pandemic has progressed, we’ve documented a trend of people detained in ICE prisons not wanting to report symptoms out of fear they will be placed in medical solitary,” said Rebekah Entralgo, a spokesperson for Freedom for Immigrants.

Despite years of evidence to the contrary, CoreCivic — which contracts with ICE to run La Palma and a number of other detention centers — denies that their facilities use solitary confinement.

“The claim that solitary confinement is used in our facilities is patently false,” CoreCivic spokesperson Ryan Gustin said. “Like most public and private secure facilities during this pandemic, we use separate housing units within our facilities to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 when someone is confirmed positive for the virus.”

Gustin said that CoreCivic has rigorously followed “the guidance of local, state and federal health authorities, as well as our government partners,” including at La Palma.

‘A nightmare’: Stuck in solitary with COVID-19

Hernandez Corbacho thought he’d finally reached safety when he first arrived in the U.S. 10 months ago. He and his wife, Maydel Curbelo Perez, had fled Cuba, where police were monitoring them for their vocal criticism of the country’s dictatorship, she said.

Using the money they had saved up for their wedding, the couple boarded a plane to Nicaragua in May of 2019, crawling up through Central America by foot and in a combination of buses, taxis and planes until they reached Nogales, Mexico. There, on the border with Arizona, they presented themselves to U.S. Customs and Border Protection for political asylum.

But things didn’t go as planned. ICE separated the two in detention. Maydel won her political asylum case in March, but Hernandez Corbacho’s court dates were repeatedly canceled amid the pandemic, leaving him stranded in ICE custody for five more months before the judge finally granted him asylum August 19.

In June, Hernandez Corbacho felt the first tickle of a cough in his throat. Hernandez Corbacho had contracted a virus that has killed over 800,000 across the globe.

But he said he was afraid to say anything. He’d heard rumors of officials locking detainees with COVID-19 symptoms in solitary, and wanted to put it off as long as possible. By the third day, his symptoms had grown severe: he had headaches, chills, nausea, and had lost his sense of smell. An official took him to see the nurse, who, inexplicably, sent him back to his cell, he said.

After vomiting throughout the rest of the day, staff finally took him to the infirmary to be tested, at the insistence of his fellow detainees. He tested positive for COVID-19.

ICE officials put Hernandez Corbacho in what he describes as an isolation cell in the infirmary, which he said was filthy: full of dirt, dust and bugs that he had to clean away himself. It was furnished only with a bed. He had no books, or entertainment, other than a Bible. There were no windows. The frequent clanging of iron cell doors, opening and closing like a cargo train, and guard radio conversations made it impossible to sleep.

I cried. I thought, he’s going to die in there – Maydel Curbelo Perez

Alone in his cell, he still felt nauseous and ill. Officials gave him an aspirin, which felt lucky — he’d heard most sick detainees got nothing. As his symptoms abated, they were replaced by anxiety and restlessness.

Across the country in Miami, his wife was panicking. She knew her husband was sick. They talked on the phone daily. Suddenly she couldn’t get a hold of him. A friend released from La Palma told her he’d seen Hernandez Corbacho taken to the infirmary, but when she called, no ICE official would tell her where or how he was.

“I was so scared,” she said. “I cried. I thought, ‘he’s going to die in there.’”

After five days, guards moved him into a solitary confinement cell primarily used to punish detainees, he said. It was also filthy, and also sparsely furnished. Three days later he was released back into the general population, he recalls. He still felt sick.

“I never thought I’d experience in the United States the kind of abuse that occurs in my country,” he wrote in an open letter to human rights groups. “I lived a nightmare.”

After the first couple days in isolation, he was able to call his wife again. On the other end of the phone, she worried for his mental health. She encouraged him to read, to write — to find some way of occupying his mind.

“At the end, he was telling me, ‘I can’t take it anymore,’” she said. “It was making him desperate.”

Why solitary doesn’t work for medical isolation

Containing an outbreak in any kind of facility — from detention centers to prisons to nursing homes — has proven a challenge even in the best of situations. For detention centers, the simplest solution, experts say, is to release as many detainees as possible.

As soon as March, thousands were released early from U.S. prisons to lower the risk of the virus within facilities — including several high-profile, white-collar criminals like Paul Manafort and Michael Cohen. ICE detainees are held on civil, not criminal, charges.

There are measures detention centers can take to mitigate the spread, like extensive testing, contact tracing, social distancing, personal protective equipment and reliable communication, said Dr. Terry Kupers, a psychologist specializing in the effects of solitary confinement. But that approach has its limits.

“Correctional facilities have a very, very poor record of doing all of these things in the best of times, and they’re not intensifying their approach during the pandemic,” he said.

Detention centers simply aren’t outfitted with the facilities to control a virus at this scale, said David Cloud, director of research at University of San Francisco’s Amend, a team of academics advocating for criminal justice reform. Solitary confinement cells are used, in part, because there’s often nowhere else for sick or exposed detainees to go, he said.

In cramped detention facilities, medical isolation can still fail to contain the spread of infection. Shared ventilation, cross-contamination and the movement of guards can still spread the virus within the facility, Kupers said.

The effectiveness of medical isolation is even more inhibited if the distinction from punitive solitary confinement isn’t clearly communicated because it can deter the sick from coming forward, Cloud said.

That means officials should strive to make detainees as comfortable as possible in isolation, safely providing them with access to medical aid, recreational activities, entertainment and some social interaction, he said. Medical isolation that feels like a punishment dissuades detainees from reporting symptoms, which can continue to fuel an outbreak.

Entralgo agrees, adding that the pandemic has amplified some of the most difficult issues facing detainees.

“Covid-19 has really exacerbated some issues that already exist within the immigration detention system,” Entralgo said. “Poor medical treatment, lack of communication with the outside world — these things have existed in immigration detention for decades.”