By August 2005, it had been more than five decades since New York-born psychiatrist and philanthropist Mortimer Sackler helped launch Purdue Pharma.

That month, the high-rolling Sackler tapped the private Swiss branch of one of the world’s largest banks, HSBC, to open a handful of new accounts.

Sackler appeared to be on a winning streak, propelled in part by the fortune his family had amassed as the developer of the drug OxyContin.

Britain’s Sunday Times had recently included Sackler on a list of the United Kingdom’s 250 wealthiest residents (Sackler renounced his U.S. citizenship in 1974 and spent time living in the United Kingdom and Switzerland). A prominent English nursery recommended a smooth-stemmed, pink rose in his honor.

Sackler and his brothers’ company, Purdue Pharma, had introduced OxyContin just a decade before to huge success. The opiate was filling bathroom cabinets across the United States and was already bringing in close to $2 billion in sales each year.

But the tide was turning. Just a month after the accounts were opened, U.S. federal prosecutors filed a lawsuit against the company that had made him rich.

The 2005 lawsuit, joined by a dozen states and the District of Columbia, alleged that Purdue Pharma had lied about Oxycontin’s risks of addiction. The claim was dismissed. Two years later, Purdue Pharma and three executives pleaded guilty to separate criminal charges of misbranding the drug as less addictive than other painkillers, resulting in fines totaling more than $634 million. No member of the Sackler family was named in the charging documents or the plea deal.

OxyContin has remained on the market.

They were among the first major salvos in a legal and public relations battle that continues to this day, pitting one of America’s most profitable drug companies and its founding family of philanthropists against a groundswell of patients, doctors, lawyers and political leaders alleging that the drug has resulted in soaring numbers of overdoses and deaths.

Last year, more than 49,000 Americans died from overdoses of opioid medications, including OxyContin.

Hundreds of U.S. states, counties and cities are now suing opioid makers, including Purdue Pharma.

In June, a lawsuit took aim at the dynasty behind Purdue Pharma, with Massachusetts suing members of Mortimer Sackler’s family.

Mortimer Sackler, who died in 2010, was among eight family members who, among others, “directed Purdue’s misconduct, which killed hundreds of people in Massachusetts,” state attorney general Maura Healy alleged in the lawsuit.

Sackler, his wife and two children were among Purdue Pharma board members who “led the deception and pocketed millions of dollars,” Healy added. Healy wants the company, directors and some Sackler family members to pay back their opioid earnings, which would be distributed to every victim statewide.

A representative of the Sackler family declined to comment.

Purdue Pharma spokesman Robert Josephson said the company shared the Massachusetts’ attorney general’s “concern about the opioid crisis” but “vigorously” denies the allegations.

“We believe it is inappropriate for the Commonwealth to substitute its judgment for the judgment of the regulatory, scientific and medical experts,” Josephson said.

Mortimer Sackler’s family reps meet with HSBC

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) explored the traces of the Sackler family empire in leaked financial records of the world’s rich and famous who used the private branch of HSBC in Switzerland.

The Mortimer Sackler family files were among 60,000 leaked documents obtained by French newspaper Le Monde and shared with ICIJ as part of the 2015 Swiss Leaks investigation.

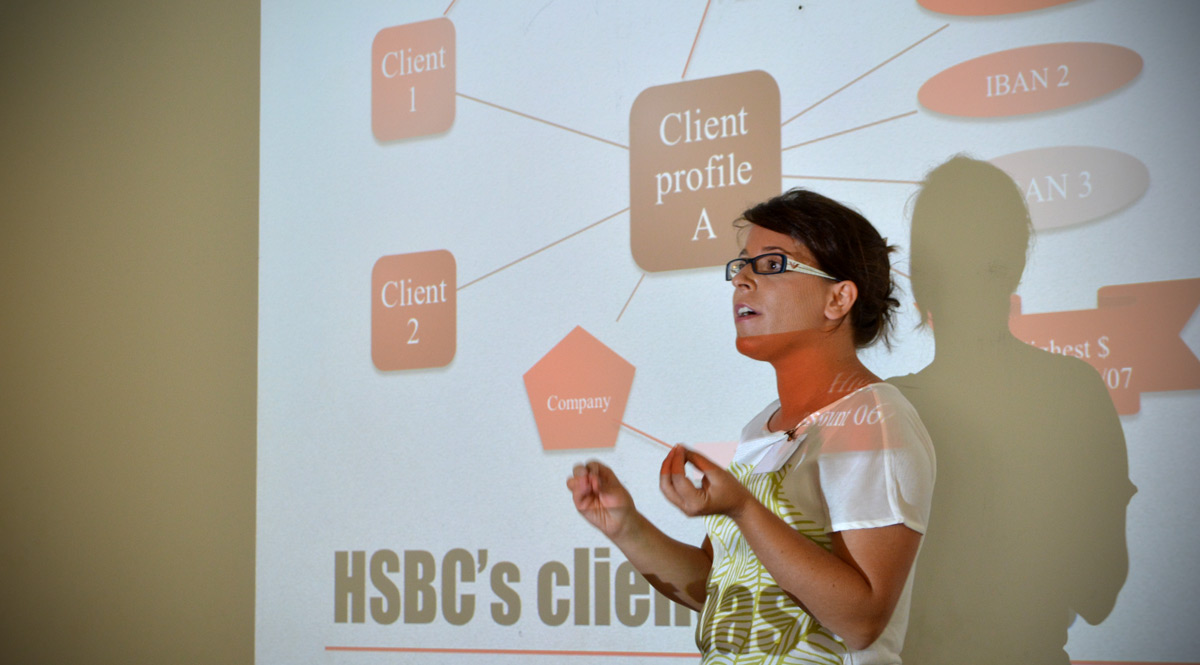

The investigation revealed the inner workings of HSBC’s Swiss branch. The bank has since acknowledged that, in general, its standards when accepting customers were “significantly lower” than they are today.

Mortimer Sackler was one of three brothers who created Purdue Pharma, which is still owned in part by his descendants and family members of his brother Raymond.

Joining Mortimer Sackler in 2005 as newly-minted HSBC clients were his third wife, Theresa, whom he married in 1980, daughters Ilene, Kathe, Marissa and Sophie and one of his two sons, Michael.

Records from the Swiss Leaks investigation show that Sackler family representatives met with bankers in 2005. HSBC employees discussed possible loan options with the family representatives and privately pondered how to manage a greater share of the Sackler family fortune, according to a record of the meeting.

Together, Mortimer Sackler’s family accumulated bank accounts with HSBC Private Bank were worth $31.2 million, including accounts that controlled the purse strings of four trusts and companies registered in Jersey, in the Channel Islands off the northwest coast of France.

HSBC’s files do not specify the Sacklers’ role in relation to the accounts and companies or suggest any wrongdoing. Like accounts in Jersey, Bermuda and other offshore locations, accounts at HSBC’s Swiss branch benefited from bank secrecy, which protects the identity of owners.

Twenty of Mortimer and Raymond Sackler’s descendants are now estimated to be worth $13 billion combined, according to Forbes magazine’s list of America’s Richest Families.

Members of the extended Sackler family have donated millions of dollars in exchange for naming rights to galleries, universities and museums. The Sackler Wing of New York City’s renown Metropolitan Museum of Art honors Mortimer and his two brothers.

The Sackler family is equally known for discretion. When Esquire magazine wrote about the family in 2017, reporter Christopher Glazek noted that “to a remarkable degree, those who share in the billions appear to have abided by an oath of omerta: never comment publicly on the source of the family’s wealth.”

Earlier this year, Britain’s Evening Standard newspaper reported that Mortimer Sackler’s family had saved $40 million by moving more than $1.3 billion through Bermuda “for the sole purpose of avoiding tax.” A spokesman said Sackler and his heirs paid taxes as required by law.

In September, the Financial Times reported that Mortimer Sackler’s nephew and Purdue Pharma former president, Richard Sackler, was granted a patent for an anti-opioid addiction drug.

If successful, critics say, the Sackler family could make millions more from a drug to undo a crisis that the company Mortimer founded helped fuel in the first place.