When one of the world’s largest engineering companies scored a $50 million deal to build a processing plant in Senegal, one of the world’s poorest countries, it looked to a tiny Indian Ocean island for help.

That island, Mauritius, has an established banking system, a level of political stability unusual across Africa and a well-trained workforce.

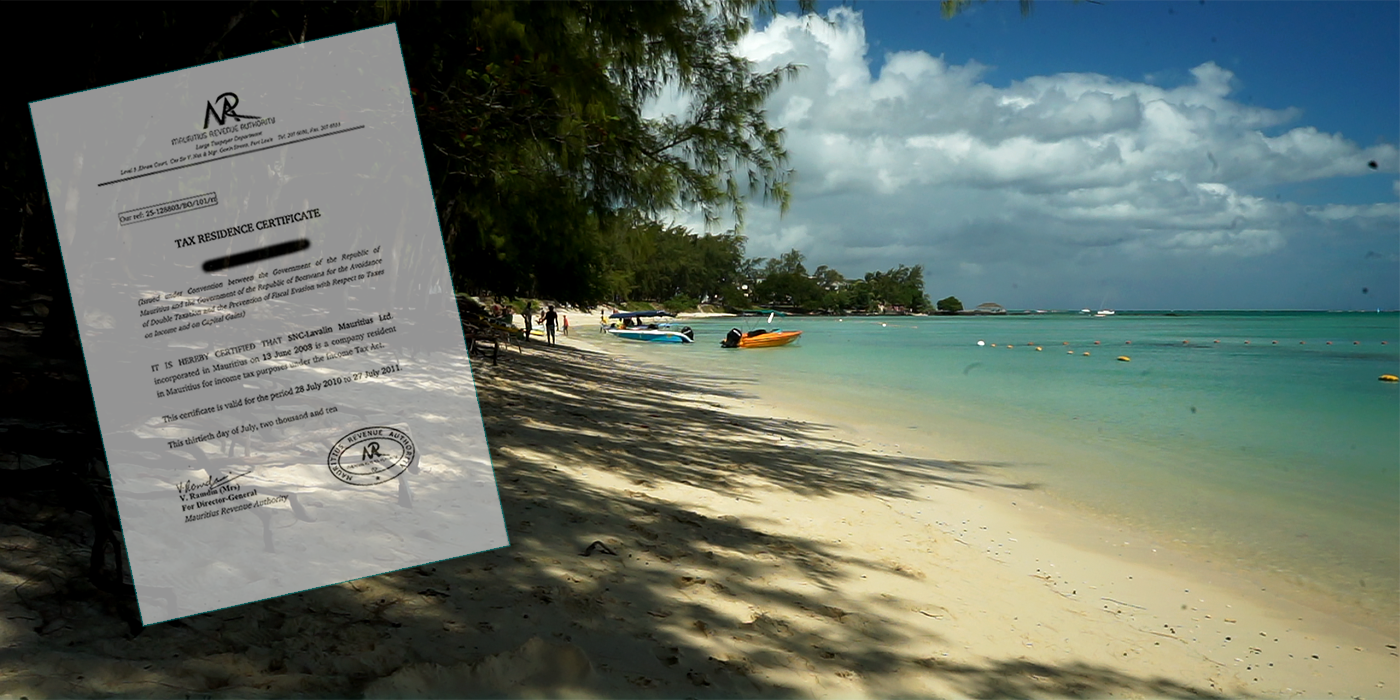

It is also a renowned tax haven.

And Mauritius offered engineering company SNC-Lavalin a significant benefit: a lopsided treaty signed with Senegal that, with the right paperwork, made it easy for the Canadian firm to avoid up to $8.9 million in taxes.

That lost revenue is no small matter in Senegal, a country where nearly half of the population lives in poverty, where 5 percent of newborns die and where one in six children are stunted by years of poor nutrition. The forgone tax would have covered half the cost of running Senegal’s largest public hospital for a year.

The Senegal-Mauritius treaty, concluded in 2004, is one among scores of agreements that keep billions of dollars in tax revenue every year from reaching poor African and Asian countries.

That was never the intention. Countries usually sign treaties to avoid taxing a company’s income twice, once in each country. Developing countries, in particular, have signed agreements in the hope that clarifying taxes paid by multinationals would encourage investment and jobs in countries that multibillion dollar operations might otherwise deem too risky.

Although originally hailed as deals that would benefit both sides of the agreements, a chorus of critics increasingly denounces treaties between wealthier and developing countries, particularly in Africa, as harmful to nations like Senegal.

Senegal is in West Africa, a poor region in one of the world’s most impoverished continents. While parts of the capital, Dakar, teem with creperies and upscale seaside fish restaurants, most of the countryside remains trapped in poverty. In remote thatched-roof villages on Senegal’s lush coast, just 2 percent of the residents receive piped water provided by public infrastructure.

In 2011, century-old Montreal company SNC-Lavalin signed a deal to design and build the $50 million processing plant for the Grande Cote mineral sands mine. At the time, the project appeared to represent great opportunity for Senegal.

The mine is now the largest operation of its kind in the world. It extracts mineral-laden sands from 60 miles of beach along Senegal’s coastline.

The sand yields, among other minerals, finely grained zircon, which is used in the United States, Norway and beyond as a glaze that brightens ceramic kitchen tiles, toilets and sinks. It also yields an ingredient in titanium dioxide, a whitener used in toothpaste.

But the mine wasn’t universally welcomed. Local tensions began to flare in 2012 during construction of the processing plant. At least seven villages were forced to make way for the project. Vegetable farmers and other residents complained of foot-dragging resettlement schemes that displaced them from more-fertile to less-fertile land.

In June 2017, members of Senegal’s parliament issued a report – obtained by International Consortium of Investigative Journalists – that faulted Grande Cote on several fronts. In particular, the report criticized the lack of diverse compensation options for those who were resettled.

On paper, the company that engineered and built the processing plant was SNC Lavalin-Mauritius Ltd, a local division of SNC Lavalin.

In reality, SNC Lavalin-Mauritius wasn’t involved. It was a shell, created for the specific purpose of helping the engineering giant avoid tax payments. The company had no construction equipment and no office of its own. It operated from inside the Mauritius office of the offshoring law firm Appleby, which helped SNC-Lavalin create the shell company.

The company’s true nature as a conduit rather than as a contractor is revealed in emails, invoices, financial statements and bank statements from the Paradise Papers, a trove of 13.4 million documents, most from Appleby, which specializes in administering tax-shelter companies.

SNC-Lavalin’s involvement with the mine ended when it finished building the processing plant. A French-Australian consortium owns most of the operation, and the government of Senegal holds a 10 percent stake.

By 2012, when almost all the work on the Senegalese plant was done, Grande Cote had paid $44.7 million in fees to SNC-Lavalin Mauritius, according to the company’s 2012 financial statements and 24 invoices.

Senegal’s taxes disappear

Experts estimate that Senegal could have missed out on $8.9 million in taxes as a result of the 2002 tax treaty between Senegal and Mauritius. Under the treaty, companies like SNC-Lavalin with a subsidiary company in Mauritius can avoid Senegal’s usual 20 percent tax on the kind of technical service fees paid to SNC-Lavalin. The final tax rate in some cases can be reduced to zero. Senegal is one of only two continental African countries with a Mauritius treaty with a zero percent tax rate.

SNC-Lavalin insists that it did not use the Mauritius company, SNC Lavalin Mauritius Ltd., with the main goal of reducing its taxes. Its reasons for choosing the tax haven, it said, instead included low political risk, a bilingual workforce, good banks and “facility for doing business in Africa.”

It could have reduced its taxes in the same way by billing for services from Canada under a treaty signed with Senegal, the company told ICIJ.

Experts consulted by ICIJ said it was unclear if the Canada treaty could have delivered the same tax benefits to the company.

Senegal potentially could tax fees under the treaty with Canada, said Prof. Vern Krishna from the University of Ottawa who is the managing editor of the legal publication Canada’s Tax Treaties. He added that Senegal’s ability to tax would be consistent with the United Nations’ philosophy of encouraging developing countries to tax income “as soon as possible.”

A spokesman for Senegal’s tax office said it signed the treaty in the hope of a win-win situation but now feels it is “unbalanced in Mauritius’ favor” and allows companies to set up in Mauritius for treaty benefits only.

It is renegotiating Mauritius and waiting for the island’s response. “Failing that,” the spokesman said, “Senegal may withdraw from the treaty – pure and simple.”

SNC-Lavalin said it was “entitled to rely on the Mauritius-Senegal Tax Treaty similar to any other company based in Mauritius.”

But experts say that tax treaties of the kind that SNC-Lavalin used to avoid paying millions to Senegal should be a thing of the past.

“You are legalizing the earning stripping-out of the country,” said Alexander Ezenagu, a tax researcher at McGill University.

“It’s a redesign of neocolonialism,” Ezenagu said, who is Nigerian. “In the 1800s, in the 1900s, they came with violence. Now, they come with sophisticated accounting systems and the lure of investment. But no country needs investment if it’s not going to be rewarded.”

A tax haven might be heaven for multinational companies to avoid taxes, but, for the country, it’s hell

Around the world, civil society, academics and members of parliament have criticized many of the estimated 500-plus tax treaties signed between developed and developing countries.

While the overall value of losses is not known, the International Monetary Fund estimated that U.S. tax treaties cut the revenue of less developed countries by $1.6 billion in 2010. Dutch nonprofit SOMO estimated that developing countries lost more than $1 billion in 2011 alone through tax treaties signed with the Netherlands. In response to fears of inequitable deals, countries such as Rwanda, South Africa, Zambia and Mongolia have cancelled or renegotiated some of their tax treaties.

Senegal and Mauritius present a sharp contrast. While a third of Senegal’s population lives in poverty, Mauritius is considered Africa’s second-most-developed country and one of its richest. When the two nations signed the agreement, officials said it would spur development in both by encouraging investment in Senegal by Mauritius.

Increasingly, however, critics say the agreement has allowed foreign companies to bypass Senegal’s tax laws with shell companies in Mauritius or elsewhere. The companies created in Mauritius generally don’t invest in Senegal, but they do provide huge tax savings to their parent companies, outside Africa, and deprive Senegal of badly needed tax revenue.

Tax heaven or hell?

“A tax haven might be heaven for multinational companies to avoid taxes, but, for the country, it’s hell,” said Ousmane Sonko, a former tax inspector who became a member of Senegal’s parliament in 2017 after running on a platform on tax fairness.

Sonko is currently lobbying other members of parliament to reject a proposed treaty with another tax haven, Luxembourg. “At the time when we should be talking about ending the tax treaty with Mauritius,” Sonko said, “they are instead talking about signing a new one with Luxembourg.” Luxembourg is also well known for its creation of shell companies.

SNC-Lavalin Mauritius’ lack of real involvement in the mining project is evident in emailed financial discussions involving the mining company SNC-Lavalin, its accounting firm Deloitte and Grande Cote employees.

“When can we expect payment?” SNC-Lavalin’s finance manager in Canada asked his counterpart at Grande Cote about the Senegalese company’s unpaid $2.6 million invoice.

Grande Cote confirmed payment after two weeks of email exchanges. The only people based in Mauritius who were included in the discussion were Deloitte accountants and offshore experts at Appleby. They did not include anyone from SNC-Lavalin’s Mauritius company.

Sonko said the tax agreement allows Mauritius and Senegal to swap information to determine whether the Mauritius company is real and whether taxes have been avoided. But often, he said, the information swap never happens. Mauritius ranks highly on corporate secrecy rankings with restrictive laws on what company information can be publicly disclosed.

“Our tax inspectors can’t just get on a plane, fly to Mauritius and do an audit of these companies,” Sonko said.

SNC-Lavalin said it created the Mauritius company in 2008 as a holding company for projects in India and Africa. The company said it balances the obligation to pay “its appropriate share of tax” against “responsibilities to its shareholders. SNC-Lavalin structures its business in a tax efficient manner while remaining compliant with all applicable tax laws.”

The multinational, which prides itself on efficiency, completed Grande Cote’s processing plant in less than two years, adding the finishing touches in 2013.

SNC-Lavalin’s need for a shell company in Mauritius was just as short-lived.

The Mauritius subsidiary reported more than $41 million in revenue in 2012 from work in Senegal. Two years later, it reported no revenue at all.

Contributors to this story: Momar Niang