There is no arguing the need for Interpol. Police cooperation between nations is vital for hampering illicit trade in drugs, weapons, people and other illegal activity across borders.

At its root there is a basic premise — that Interpol’s member states subscribe to common values and mores and should not abuse the tremendous power over individual rights given to the organization by virtue of its status as a worldwide police dragnet. But that isn’t the case. Countries that are recognized as chronic violators of human rights, like Russia, Iran and Venezuela should not merit the same credibility as other member states in their use of Interpol.

There is substantial evidence that these rogue states are abusing international agreements, originally designed to control crime, to pursue regime opponents and persecute targeted individuals. Extradition requests, which often have little chance of success but guarantee a prolonged confinement without charges (minimum 40 days in Europe), are becoming more common. And the Interpol Red Notice, which creates a virtual prison around its subject, preventing travel outside the country of residence, is the coup de grace in the arsenal of these abusers.

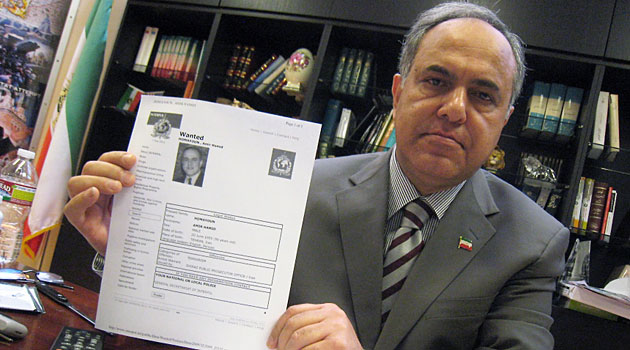

I know firsthand that an Interpol listing is equivalent to a conviction, without a legal procedure. After Russia placed me in the Interpol database in late 2007 my bank accounts in the U.S. were suddenly closed. In February 2008, I was arrested during a routine passport check close to the German-Danish border. As a result, I spent 50 days in a maximum security jail in Lubeck without being charged by the German authorities, simply on the basis of the Interpol Red Notice. That country ultimately decided my Red Notice was politically motivated. After my release, the Germans provided me with an armed three-car escort “for protection from the Russians” to the Danish border. Because Interpol operates with complete immunity from any judicial authority there was no compensation for my unwarranted detention or legal costs.

When faced with demands for greater transparency and accountability, Interpol responds that it is only a clearinghouse for information, a database to help police organizations update their colleagues around the world with information about fugitives who might be crossing their borders. That is disingenuous. The central problem with Interpol is that it is accountable only to itself and its member states. It has no effective, binding judicial oversight and it can easily be manipulated by members with their own agenda.

Interpol needs to accept a clearly defined and transparent procedure for reviewing challenges to Red Notices. That requires judicial oversight, which must be maintained by an independent legal authority, like the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. It is utterly irresponsible to maintain an opaque system of handling disputes in light of the dire consequences suffered by those placed on Interpol’s database. At the very least, the subjects of Red Notices should have an opportunity for a hearing and a chance to plead their case. Currently, any information provided by the subject of the notice is passed directly to the member state which placed him or her on the list. Currently, the only certain way of being removed from the list today is to have the country (Russia in my case), which put you on the list inform Interpol that it is no longer interested in pursuing the matter.

As more and more cases like mine come to light, Interpol is losing credibility. Besides a tarnished image, it risks diminishing its ability to get police organizations to act on genuine notices — ones not tainted by a political agenda of a corrupt regime. There should not be any doubt on the receiving end of a Red Notice that the individual sought is likely to be a fugitive and not some unlucky political opponent or a businessman whose company was just too good a target to pass up by government interests.

The author, a U.S. citizen, has been listed in the Interpol database for the past four years at Russia’s request. Denmark, where he resides with his family, refused to extradite him in 2009. In the U.K., a court ruled that the charges against the company he is associated with were “political in nature.” He has provided testimony to the U.S. Congress detailing the abuses of Interpol by Russia.