When Iranian political activist Rasoul Mazrae sought shelter from his own government, he fled, headed for Norway via Syria.

He was followed by a petition from Iranian officials that Interpol, the international police agency, list him as a fugitive. Despite the United Nations recognizing him as a political refugee, the same Syrian government that today is cracking down on its own dissidents used that Interpol alert to deport Mazrae to Iran in 2006.

Mazrae was jailed for two years. His family told a UN rapporteur he was tortured to the point of paralysis, had blood in his urine and lost all of his teeth.

Mazrae was sentenced to death, and human rights observers lost track of him. “We are not aware that his death penalty has been carried out, but we cannot be absolutely sure,” said James Lynch of Amnesty International.

What Syria and Iran used to go after Mazrae was an Interpol “Red Notice.” This system of notices, little known outside legal circles, is being exploited for political purposes by some of the 188 member nations that belong to the 88-year-old international police cooperation agency.

Interpol’s primary purpose is to help police hunt down murderers and war criminals, child sex offenders and wildlife poachers. But a five-month investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists shows a little-known side to Interpol’s work: In cases from countries such as Iran, Russia, Venezuela and Tunisia, Interpol Red Notices are not only being used for legitimate law enforcement purposes, but to round up political opponents of notorious regimes.

For countries that want to abuse Interpol, “it’s a way to extend their arm to harass opponents – political or economic,” said Kyle Parker, policy director of the U.S. Helsinki Commission, a human rights body of the U.S. Congress.

ICIJ analyzed a snapshot of Interpol’s Red Notices, published on December 10, 2010. It includes 7,622 Red Notices issued at the request of 145 countries. About a quarter of those were from countries with severe restrictions on political rights and civil liberties. About half were from nations deemed corrupt by international transparency observers.

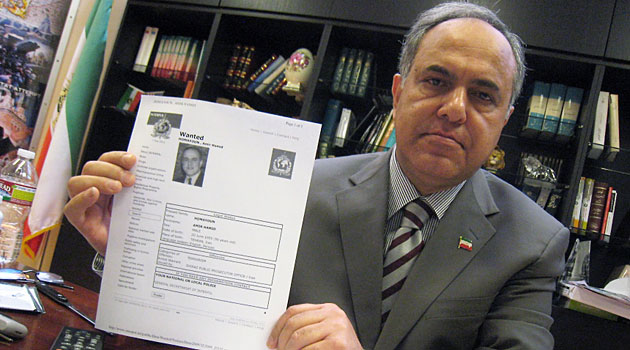

The Islamic regime of Iran’s use of Interpol stands out not just because of the Mazrae episode, but also because of people like Shahram Homayoun.

He fled Iran in 1992 after the mullahs took over. After he settled in Los Angeles, Homayoun started a satellite TV station to beam a message of civil resistance into the homes of Iranians.

His audience has scribbled his slogan in Farsi, Ma Hastim – “We Exist” – on walls and bridges around the country. In 2009, he called on Iranians to gather at the tomb of the ancient Persian ruler Cyrus the Great. That’s all. Just show up at his tomb, like a flash mob. That fall, he prompted Iranians to show up at their local bakery every Thursday and ask for bread.

He’s definitely a troublemaker.

“Apparently, the Interpol thinks so too,” Homayoun said, laughing at a reporter’s quip.

In December 2009, Iran charged him with inciting “terrorism against the Islamic regime such as writing slogans [on walls] and resisting the security forces,” and, at Iran’s request, Interpol issued a Red Notice and put Homayoun on its global most-wanted list.

Now officially an Interpol fugitive because of the Red Notice, Homayoun can’t leave the United States. He’ll probably never again see his parents in Iran. Fortunately for Homayoun, the U.S. won’t arrest him, let alone send him to Iran.

How the System Works

Interpol Red Notices originate from police in member countries who send them as domestic arrest notices. Interpol then generally sends them out as global Red Notices. The notices allow police in other countries to arrest suspects for extradition.

The agency operates a closed communications system linking police via vast international databases. Interpol works to raise police standards with training in forensics and investigations. It plays an essential and celebrated role in fostering international cooperation. Its current chief is Ron Noble, a former U.S. federal prosecutor and oft-mentioned candidate to one-day lead the FBI. Noble has served as chief of the Secret Service, U.S. Customs and the bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

In theory, Interpol cannot get involved in “any intervention or activities of a political, military, religious or racial character,” according to its constitution.Interpol’s member nations span from democracies to dictatorships. Iran and Libya are members. Their requests to Interpol are treated the same as those from democracies like Canada, Britain or France.

Interpol’s chief lawyer, Joël Sollier, said the agency works hard to ferret out cases chiefly motivated by politics, rather than crime. “If we don’t,” he said, “we are dead.”

International cooperation is based on trust. If Interpol is seen as political, Sollier said, it loses credibility.

But there’s no way to publicly determine how often Interpol catches politically motivated cases. Here’s why:

Interpol, the world’s largest international police organization:

- Isn’t transparent. It doesn’t have to share any data with anyone, other than its own police members, and its own appeals body. Its operations are mostly opaque, in the name of protecting sovereign law enforcement information. The statistics it publishes don’t reveal how often it finds cases are political, or when its power has been abused.

- Isn’t accountable to any outside court or body. That’s because Interpol isn’t a creature of governments. It’s more like a huge, private police club.

- And Interpol is putting more power into the hands of national police forces — partly to save time and money.

Critics of Interpol — lawyers who’ve dealt with it and human rights observers — say Interpol’s workings make it vulnerable to abuse by countries that target people for political reasons.

And, they say, countries use Interpol’s Red Notices against their enemies because it’s a terrific weapon. International banks will close accounts. If subjects cross some borders, they can wind up locked up for months with no recourse, or sent back to the country pursuing them.

“It’s not like fighting a criminal charge,” said the U.S. Helsinki Commission’s Kyle Parker, who has studied how Russia uses Interpol.

“A Red Notice can be even more effective than the judicial system — with none of the safeguards … It doesn’t prosecute you; it persecutes you.”

Interpol says it is constantly working to make its system better. But its chief lawyer Joël Sollier acknowledged Interpol has limits.

“You receive something from a country where human rights are not respected … where the independence of the judiciary is far from perfect. … You never know,” he said. “I would love to have only requests from Switzerland, you know? It’s not the case. The world is not like that.”

Nearly half of published Red Notices in the snapshot examined by ICIJ were from countries in Transparency International’s index of countries listed as most corrupt on its global corruption index. It measures perceptions of corruption, including in law enforcement and the judicial system. Those countries include Honduras, Albania, Russia, Belarus, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, Ukraine, Vietnam, Paraguay, Tajikistan, Venezuela, Libya, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Iraq and Iran.

More than 2,200 of the published Red Notices were from countries listed as providing no political rights or civil liberties by the independent non-governmental organization Freedom House. These include Russia and Belarus — the fourth and fifth most frequent sources of public Red Notices seen by ICIJ.

Among the top 30 countries requesting public Red Notices were Azerbaijan, the United Arab Emirates, China, Rwanda, Vietnam, Tajikistan, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Iraq and Iran.

So what measures does Interpol take to prevent political abuse? And how often does it catch problems?

There’s no way to find out how often.

Interpol Isn’t Saying

Interpol won’t share any figures on the number of Red Notice requests it rejects because of political reasons — as it did, for instance, when Ecuador asked Interpol to list Colombia’s defense minister for his role in a raid on Colombian rebels inside Ecuador.

Interpol’s press officer, Rachael Billington, insisted Interpol isn’t keeping secrets. She said it’s just not possible to determine how many political cases there are in Interpol’s databases.

“What may appear initially to be an Article 3 [a political case] may eventually be assessed as complying with Interpol’s rules and regulations,” Billington wrote. “Similarly, a Red Notice request may be refused for reasons entirely unrelated to Article 3, for example [the local police member] has failed to provide the necessary information required to issue a Red Notice, such as details of the arrest warrant, or not enough data has been included.”

Yet Interpol has guidelines of practice for dealing with political cases that are chock-full of “real-life examples” of how Interpol has dealt with them.

For instance, in one of many cases cited by Interpol’s practice guidelines, Interpol rejected a Red Notice request by police in one unnamed country that had charged a person from another country with espionage.

“It was concluded the charge and facts provided were of a purely political nature,” Interpol wrote.

Interpol refused to give ICIJ any indication or estimate of how many cases Interpol deals with that are political in nature. The only figure its press office would provide is that roughly 3 percent of its cases are referred to Interpol’s lawyers for review.

That means there’s no way to tell how often, for instance, Interpol reverses itself on Red Notices it has published because of political concerns.

That is just what has happened with Venezuela.

In recent months, Interpol has blocked more than two dozen published Red Notices obtained by Hugo Chavez’s government — against bankers and former political leaders who allege they’re political targets of Chavez.

One of them is Manuel Rosales, who lost to Chavez in the 2006 presidential election and has been a leading opponent of Chavez. Interpol put him on its most-wanted fugitive list in 2009 — after Rosales sought, and later won, political asylum in Peru.

Since then Rosales has been quietly scrubbed from Interpol’s public website.

Another is Nelson Mezerhane, former owner of Banco Federal and former owner of the opposition news channel Globovisión.

Interpol is now vetting every request from Venezuela more closely.

So how often do countries get away with abusing Interpol with political cases?

Billy Hawkes heads Interpol’s appeals body – it handles complaints from people on Interpol’s fugitives list who say they are targets of political prosecutions.

He said the number of abuses that come to light is low, relative to the thousands of Red Notices Interpol issues each year.

For instance, he said only 21 of the 215 complaints filed in 2009 with Interpol’s appeals body — called the Commission for the Control of Interpol’s Files — specifically claimed they were being targeted because of politics.

But not every possible abuse ends in a complaint. Homayoun, the Iranian satellite television owner, for instance, had not filed a complaint with Interpol’s appeals body when ICIJ interviewed him.

Cases Against Dissidents

In the public Red Notice database, published reports, court documents and interviews with lawyers and other experts in Interpol’s process found at least 17 countries in the last five years have used the agency to go after dissidents or political opponents, economic targets or environmental activists.

Among the cases:

- Sri Lanka used Interpol to go after the owner of a website that publishes articles critical of the government. The government charged him with counterfeiting and forgery — years after he had left the country — and only after it had failed to ban his website inside Sri Lanka.

- China used Interpol to target Uighur political leader Dolkun Isa, whom Germany had designated as a political refugee.

- Pakistan used Interpol to list the late former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto as a fugitive on corruption charges — then cancelled the Red Notice after she met for political talks with former military leader Pervez Musharraf.

- Iran has used Interpol to go after at least a dozen political dissidents who have been living in Sweden and other European countries for years — all of them political refugees.

- Tunisia’s former regime used Interpol to pursue members of the Islamic opposition party Al Nahda — some simply for belonging to the banned party.

- Bahrain used Interpol to list Shia opposition leader Hassan Mushaima on terrorism charges. During the recent Arab protests, Mushaima was arrested in Lebanon on the Interpol notice — until human rights groups protested. The government dropped the charges as part of a peace offering with opponents and let Mushaima return to Bahrain — then arrested him on his return. An Arab news agency reported in mid-April that Bahrain had placed Mushaima in a military hospital “because of the deterioration of his health and hunger strike.”

- Russia has used Interpol to pursue at least a dozen business people linked to Vladimir Putin political opponent and oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky — and his former oil business, Yukos. Many of them have received political asylum, based on Russia’s pursuit, or a judge has deemed their cases “politically motivated” and refused to extradite them.

One of them is Ilya Katsnelson, a Russian-born U.S. citizen whose shipping company did business with a Russian company related to Yukos. In its grab for Yukos, Russia charged Katsnelson with tax evasion, fraud and money-laundering — involving the Russian company that he didn’t own, manage or have any influence over.

Russia has used Interpol to pursue him for five years.

Because of that, Katsnelson spent 50 days in a maximum security German prison after he tripped the Interpol alert.

Both Denmark and Germany have reviewed Russia’s case against him and refused to extradite him to Russia. After its review, Germany sent him home from prison with an armed escort. “We have to protect you from the Russians,” he recalled the Germans telling him.

A British magistrate found Russia’s case against his business partner to be “likely politically motivated.”

Interpol’s Political Dance

Interpol won’t talk about specific cases or countries. But its officials say their job is complicated in cases where politics mingle with allegations of crime.

In the case of a coup, for instance, a new regime indicts the ousted leaders for corruption. Politically motivated, right?

Not always, said Interpol’s chief lawyer Joël Sollier, an affable Frenchman who left the United Nations to head Interpol’s legal affairs office in 2008.

He said in the coup scenario, the grounds for prosecution may well be true — even though the context is political.

“Sometimes it’s really tricky, you see,” Sollier said during an interview at Interpol’s headquarters in Lyon.

Sollier, a former judge, helped draw up the guidelines Interpol lawyers use to consider whether a case violates Interpol’s ban on political cases.

“Neutrality is, and always has been, paramount to Interpol,” reads Secretary General Ron Noble’s foreword to the guidelines. “It is of the utmost importance that our activities transcend domestic and international politics. “

The guidelines explain Interpol’s decision-making process in cases involving former politicians, for instance, and its approach to cases that could be political — for example, criminal charges that arise from election activity.

In the end, the guidelines call for a case by case review of the facts underlying a particular case.

Billy Hawkes, the head of Interpol’s appeals body, likes to quote the old adage that politics is in the eye of the beholder: “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.”

But Interpol has another, structural hurdle to overcome in ferreting out political cases.

“Interpol is not like the United Nations,” says Philippe Neyroud, a lawyer in Geneva who has represented people on Interpol’s Red Notice list. “It’s just like the Jockey Club.”

Because Interpol answers only to its police members and its own appeals body, Interpol’s decisions and actions are geared toward maintaining police cooperation. Among other things, this means not ruffling too many feathers among its members.

Interpol’s operations are based on the presumption that police are telling the truth and are acting with integrity. It’s actually written in its rules.

In winter, on a gray day, lawyer Yaron Gottlieb sat inside Interpol’s fortress-like headquarters in Lyon and explained Interpol’s Red Notice process.

“We assume that what we receive here is accurate and relevant,” said Gottlieb, a friendly, intense young lawyer who has been with Interpol since 2005. “That an arrest warrant is issued by a judge who is not corrupt. And of course, that the case is not political. But then, if we receive information or if we have our own information — that in fact, the case is different from what it seems to be — we engage in a full review.”

Sometimes, Gottlieb said, lawyers or Interpol’s appeals body will flag a potentially political case. Sometimes, a third country will ask Interpol whether a certain Red Notice is political, and that will trigger a review.

Interpol will also sometimes flag a case after hearing about it on the news. The nerve center of Interpol is a room with a wall of TV screens beaming in cable news channels and top stories from around the world.

“We’ll say, hmmm, let’s check if we have already published it,” Gottlieb said. “And maybe the [front office] has published it already. But then, we can always reopen a case for review.”

In other words, Interpol has developed a fluid, informal system for catching political cases. It can turn to regional experts and information from defense lawyers, human rights groups and court decisions to help decide about particular cases.

As its chief lawyer, Sollier said his personal instruction is to simply cancel a Red Notice when there’s a doubt.

But Interpol doesn’t have independent investigative powers. And its purpose is not to get to the truth of a case. It’s there to help its members — the police.

So Interpol’s view of a political case doesn’t always match others’ views.

Take the case of Wikileaks’ Julian Assange. When Sweden wanted to question Assange on allegations of rape, they got Interpol to issue a Red Notice — just to arrest him for questioning. Assange’s lawyers charged the case was political, aimed at shutting him and Wikileaks down.

Sweden — and Interpol — saw it differently.

A former senior U.S. State Department official told ICIJ that the U.S. government routinely marked some Interpol Red Notice cases as “politically motivated” — when Interpol had not.

For instance, in 2005, the U.S. let in two partners of Mikhail Khordokovsky on Interpol’s fugitives list — Mikhail Brudno and Vladimir Dubov. They joined President Bush at a National Prayer Breakfast.

The U.S. Interpol office, based in the Justice Department, refused an interview for this story.

Why does it matter whether Interpol gets it right? After all, Interpol doesn’t have the power to arrest anyone. It just puts people on a most-wanted fugitives list.

Being on that list can change your life — or end it if you get extradited to a country that doesn’t follow the rule of law.

You can be on Interpol’s list even if you’re a political refugee — and have won protection from the very country that is pursuing you through Interpol.

There’s nowhere for a fugitive to turn when Interpol makes a mistake — and when it’s not safe to return to the country behind that mistake.

Mistakes are something to think about — at a time when Interpol is growing rapidly — and is automating more of its work.

In 2005, Interpol issued 2,343 Red Notices. Last year, it was 6,344.

Partly to deal with that increased workload, Interpol is putting more power into the hands of its police members.

Two years ago, police had to apply directly to Interpol for a Red Notice. Today, every Red Notice request is entered into the system directly by the police themselves — not by Interpol. Police around the world instantly see those notices — before Interpol even reviews them.

Police can also bypass the formal Red Notice system altogether — and just type an informal notice of arrest in an email — and post it on Interpol’s communications system. Those email notices — Interpol calls them “diffusions” — go out instantly — with no automatic Interpol review.

Diffusions are pretty popular among Interpol members. Tunisia just used one to pursue deposed President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali.

And these informal email notices are linked to far more arrests than arrests linked to the Red Notices Interpol vets for political concerns.

Interpol says it knows of 1,858 arrests last year of people named in these email notices. That’s more than twice the number of arrests last year — 663 — of people named in Red Notices, that Interpol says it’s aware of.

A Recipe For Abuse

To critics, Interpol’s workings add up to a recipe for abuse — by countries run by dictators or human rights violators or countries without independent judiciaries.

“I think the process is unfair,” said Anand Doobay, a British lawyer who has defended people on Interpol’s list. “There’s no transparency to it. It’s weighted in favor of law enforcement and the need to prevent and disrupt serious crime and terrorism. There’s very little by way of protection to keep the state — or even one corrupt prosecutor — from misusing the process.”

It boils down to Interpol not being subject to any outside oversight, said Philippe Neyroud, the Geneva lawyer. “So when there’s an abuse, there’s almost no remedy.”

“Interpol is doing lots of good things, thank God!” he said, adding that “nobody does just good things” without sometimes doing the wrong thing.

Roger Gherson, a London-based immigration and human rights lawyer, said, “In this day and age, to have any policing authority without the ability to be monitored by any independent body is not a healthy thing to have.”

Interpol points to its own appeals body as a remedy for those who believe they have been wronged. Interpol created the Commission for the Control of Interpol’s Files in the 1980s to help it navigate the seas of international data protection — and handle complaints from people who say they are political targets — like the shipping magnate Ilya Katsnelson.

Billy Hawkes is head of Ireland’s data protection authority; he chairs the part-time board of the commission. He is a warm and public-minded man who is clearly dedicated to using the commission to try to keep Interpol within the lines of international law and data protection law.

Last year, the commission recommended Interpol remove 21 cases from its databases altogether because of problems. It called for Interpol to remove another 73 notices from its public website — although police can still see them, and act on them.

But the commission has limits. It can’t investigate cases on its own and its recommendations are not binding on Interpol.

Hawkes said there is “clear understanding” that Interpol will follow the commission’s recommendations, even though there is no legal obligation to do so.

And while its board members are independent, Interpol funds and staffs the commission.

Interpol’s rules dictate that any finding by the commission that a certain case is political, or a finding by Interpol’s staff, can be overturned by a simple majority vote of its members — the police.

“It winds up being a diplomatic decision, a political decision that concerns the political freedom of a person,” said Mario Savino, a legal expert who has written about Interpol.

That is what happened to the former prime minister of Kazakhstan, who found his country asking for a Red Notice on him after he opposed the president. Interpol rejected the request, after judging it political. At Interpol’s next General Assembly, the police members voted to reinstate the Red Notice. And Interpol did just that.

Secretary General Ron Noble said after the vote: “Interpol is a democratic organization, and when our members have expressed their will through the democratic process, the general secretariat moves promptly — as in this case — to implement the member states’ decision.”

In other words, Interpol follows the rules of the club.

*Editor’s note: A previous version of this story erroneously listed North Korea as an Interpol member. North Korea is not a member of Interpol.