Consumers in Spain trust the mild-flavored white flesh of hake, the most popular fish in a country that eats more seafood than almost any other in Europe. Hake is considered safe for pregnant women, and kids crunch into the cod-like fillets as fishsticks.

“There’s trust because of the cultural bond,” said Cristina San Martín, head of quality and food safety at Fedepesca, a trade group representing Spanish fish retailers. “You see it from the time you’re a kid, and it also has a good price.”

What Spaniards probably don’t know is that the fish they take home for dinner might not be hake at all.

The Spanish public is being cheated by a seemingly pervasive and dangerous form of commercial fraud: Different species — including cheaper fish such as catfish from Vietnam and grenadier from the Pacific Ocean — are sold as hake in markets across Madrid. A DNA study commissioned by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists found in July that nearly one in 10 fish were mislabeled. A study completed last year by the same scientists found mislabeling in nearly 40 percent of samples.

“Some of the revealed cases are really ‘cheeky’ and shockingly blunt attempts to fool consumers,” said the European Commission’s top fisheries DNA expert Jann Th. Martinsohn, who reviewed ICIJ’s methodology and findings. “And worse, they are not unique.”

Hake is big business in Spain, where sales exceed €1 billion a year. Mislabeling could bump the bottom line of companies that pass off cheap fish as higher-quality fillets, and may even mask illegal fishing, marine biologists and economists say. The European Union has strict regulations requiring that a paper trail follow fish from ship to shop. But the law doesn’t require that inspectors implement DNA testing to verify accurate labeling.

“The majority [of mislabeling] is commercial fraud,” said Ricardo Pérez, DNA expert and investigator of the Spanish National Research Council. “In recent years there’s been an increase of it, I think because companies know they’re not being watched.”

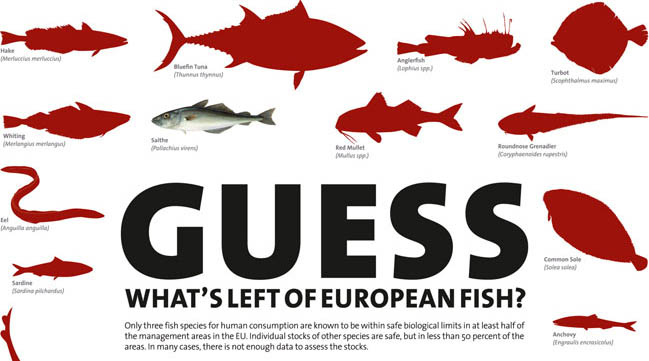

Mislabeling seafood is a global phenomenon. The environmental group Oceana reported in May that studies in different countries around the world found between 25 to 70 percent of the fish being mislabeled. In the United States, tilapia was sold as red snapper. In South Africa, mackerel was sold as barracuda. In New Zealand, protected hammerhead shark was sold as lemon shark.

Europe’s top department store El Corte Inglés pulled a batch of more than a ton of mislabeled fish from its shelves when told of ICIJ’s findings. The majority of markets that carried mislabeled fish attributed the problem to human error. And every one of the eight shops where ICIJ found mislabeled samples said it was a one-time occurrence. Authorities in Spain seemed to agree. They said they didn’t think the results of ICIJ’s study were significant enough to show a trend, or present a major threat to the public.

Almost half Spain’s consumers buy their food in or near Madrid. Yet in 2010, regional and city authorities taxed with controlling consumer goods used scientific testing to identify fish species of 59 samples — about a third the number included in the ICIJ study. One thing appears clear: Consumers are largely ignored in the equation.

“What they [authorities] answer, is, ‘will somebody die? No. Well, then it’s only money,’” said Gemma Trigueros, nutritional coordinator at the Spanish Consumers and Users Association (OCU).

What’s on your plate?

Hake is found across the globe — from Argentina and Namibia, to Ireland and New Zealand — and there are at least 12 distinct species of hake in all. Some, like southern African hakes, are cheap. Others, like European hakes, return a higher profit.

Spain imports more than 60 percent of the hake coming to the EU. So scientists at the University of Oviedo in Spain partnered with a Greek university and last December published findings of a multi-year study. Their results showed that more than one in three hake products sold in Spain and Greece were not what they appeared. Researchers identified a trend: Cheap species were sold as higher-priced European or American hake, leading scientists to deduce that companies were committing fraud.

Eva García Vázquez, the primary author, did not publish company names in her report and declined to share those with ICIJ, although she said she would have given the information to the government, had officials asked.

So ICIJ undertook a sampling in Madrid to find out if the mislabeling continued and what companies were involved. In June, reporters collected 150 hake samples from major supermarkets, fishmongers and bulk suppliers. ICIJ commissioned the experts at the University of Oviedo to conduct a blind DNA analysis of those products.

DNA testing is better known for its use in forensic analysis, publicized on TV programs like CSI. Yet the tests are today fairly simple, cheap and quick. And they have a wide range of uses. Thanks to an enzyme-based technique developed in the 1980s, scientists can obtain the DNA sequence from a fish and, by matching it to an online database, identify the species in just one day.

ICIJ’s analysis showed that 8.6 percent of samples were mislabeled. The researchers concluded that the actual level of mislabeling is likely much higher than what ICIJ’s snapshot study has documented.

‘Surely Deliberate’

The most worrisome findings involved entirely different families of fish being sold as hake. Long-bodied Patagonian grenadier from the southern ocean, bulbous-eyed Pacific grenadier found off the coast off of California, and striped catfish pulled from rivers in Vietnam look nothing alike when they’re swimming. Yet as a frozen fillet, most shoppers just see white fish.

But the fish dealers can tell.

“They don’t even look alike,” said Gonzalo González, a fishmonger whose family has been selling fish since the 1920s and is president of Fedepesca. “Some are whiter than others — like detergent commercials say.”

This helped experts at the University of Oviedo conclude that swapping species was “surely deliberate.”

When alerted to the ICIJ findings, El Corte Inglés, Europe’s largest department store, took immediate action to independently verify the problem. The high-end market said it conducted its own DNA analysis of seven batches of the mislabeled product and found that the samples from one shipment of 1.4 metric tons were also mislabeled.

“We’ve withdrawn that entire batch from our shops,” said a spokesperson for the store. “We’re in conversations with the provider to take drastic measures.” She declined to share the provider’s identity for “confidentiality reasons,” and said El Corte Inglés has started to carry out genetic testing of fish as part of its routine quality controls.

ICIJ also encountered problems with products sold in top supermarket Alcampo from Spain’s leading fish exporter, Freiremar. Two products of its brand Nakar were mislabeled — one was a different species of hake, the other was a Pacific Ocean grenadier. Freiremar said it doesn’t regularly conduct genetic analysis “unless there’s a well-founded suspicion.” Freiremar asked the supermarket to withdraw the products identified by ICIJ’s study as Pacific grenadier “as a precautionary approach.”

All the experts who weighed in on the study said the most egregious finding was the case of Vietnamese striped catfish sold as hake by a local fishmonger, Pescados El Bierzo. This river species is criticized for higher contamination levels and lower nutritional value than other fish.

The shop is housed in a market serving immigrants in Madrid’s city center. Its manager Vicente — who declined to give his last name — said ICIJ caught a one-time error, not a widespread practice. He said various types of bulk frozen fillets are separated only by plastic sheet. The mislabeling likely occurred by a “fillet of catfish jumping into the hake area.”

Health at stake

Researchers at the University of Oviedo warned that cases where a different fish than expected is sold could cause “severe health problems to unaware consumers.”

Allergist Dr. Beatriz Rodríguez of Madrid’s Getafe University Hospital said that while normally people are allergic to fish generally, it’s increasingly common to develop sensitivity to one particular species group — like catfish. Kids are the most vulnerable.

“If I tell the mother: avoid catfish and then she buys hake thinking she’s safe, the child could have a severe allergic reaction,” she said, causing hives, diarrhea or even problems breathing.

In Hong Kong, more than 600 people became violently ill in 2007 after eating what they thought was “Atlantic cod” — and turned out to be poisonous oilfish, named for the indigestible wax esters in its flesh.

Scientists warn of other health risks with fish mislabeling: pollutants, toxins and other harmful substances like mercury specific to geographic regions or species. Health officials in the EU and Spain said there are currently no health alerts caused by fish mislabeling.

National fish sells

Sergio Sánchez manages Pescados y Congelados Conchi, a bulk foreign fish shop where both of ICIJ’s hake purchases were mislabeled. He said when he buys fish for his shop, he cares about the best-by date and appearance. He said some consumers turn up their noses when told the truth about the origin of fish.

“National species sell. You tell people that hake is from Chile and they don’t want it,”

Sánchez said. “You tell them shrimp is from China — and not from Huelva [in southern Spain] — and same thing.”

Supermarket chains Alcampo, Hipercor, Eroski and Carrefour each blamed a one-time error by an employee. All the markets said they adhere to strict quality controls. Carrefour said it “last year … rejected 188,909 kg (for not being correctly labeled or because they did not meet minimum size requirements).”

In the cases where more expensive European hake was billed as cheaper hake species, Alcampo said the consumer wins. “We were giving the client a product of higher quality than what the label said,” the company wrote in an email response.

Stefano Mariani of the University College in Dublin, thinks cases like this may point to another problem: overfishing. When a boat reaches its quota, it must stop targeting that type of fish. But any additional catch could be laundered into the legal market as a different fillet, Mariani reported in a study published earlier this year.

“Would you accept getting pig meat when you buy beef? Absolutely not,” he said. In a tightly controlled market like the EU he finds the problem alarming.

European hakes are subject to strict catch limits under recovery plans, a result of decades of overfishing. Meanwhile fishmongers have been complaining about the low prices they’re getting for the fish, which leads some vendors to conclude that fishermen aren’t adhering to the quotas. The Ministry of Environment, Agriculture and Fisheries denied Spanish vessels are exceeding hake quotas .

Law and disorder

EU law requires a label follow the fish from net or farm to the final vendor.

The Health and Fisheries ministries are required to verify that imports are really what they appear. The latter is also taxed with inspecting fish landed at Spanish ports. The Fisheries ministry did not provide the number of inspectors, although it said more than 200 people were involved in their entire control operations.

Neither ministry would comment on ICIJ’s findings, saying they could not “draw general conclusions.” They did not respond to questions regarding the earlier multi-year study by the University of Oviedo.

No EU law requires member countries to conduct DNA testing to find out if labels and products match. And most — including Spain — largely do not employ such testing.

Several authorities share control of tracking fish, safety and labeling in Spain. The fractured oversight allows individual authorities to shrug off blame. Regional governments oversee supermarkets, restaurants and factories. The Madrid regional and city governments administer products for a region comprised of more than 7 million people and the world’s second-largest fish market.

Yet officials there scientifically tested just 59 fish to verify the species in 2010. José Manuel Torrecilla, manager of the health authority in the city of Madrid, acknowledged they do very few tests on fish identification, but said the city plans to increase the number in coming years.

“It’s more important what causes a health risk to consumers: contaminants in fish and its freshness,” he said, pointing out that the city labs conducted about 500 tests for freshness and contaminants in 2010.

Scientist Ricardo Pérez has been conducting DNA analysis of fish for more than two decades. He said he feels frustrated because regional governments just aren’t interested in what he offers. “There’s no money for that,” they tell him.

“You develop interesting tools for governments to improve control, and it’s almost impossible to get them to do something,” he said.

The EU Commission research center recently published a study showing how scientific techniques such as DNA testing are vital to fight illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. Co-author Jann Th. Martinsohn told ICIJ the cost of scientific testing is no longer prohibitive — it can be as low as €35 per sample if you test in bulk.

Martinsohn has spoken to officials across the EU, pushing governments to implement the kind of testing that private industry has been doing for years. Spanish officials told him the Fisheries ministry only does sporadic DNA testing, while the industry group Anfaco has its own private laboratory.

Carlos Ruiz, technical and policy coordinator of Anfaco, told ICIJ its lab conducts 47,000 tests a year — about 1,000 of them being DNA analysis of the species. But they don’t share results with the government unless it’s a commissioned job paid for by officials. And those are rare.

“This is a private lab,” Ruiz said. “We’re not watchdogs of the market.”

Martinsohn lists Denmark as one of the most advanced countries in the EU on the use of DNA analysis in fisheries enforcement. The Danish Fisheries Inspectorate collaborates with the public university to conduct the testing. Inspectors there carry small toolboxes to obtain tissue.

Pérez, the Spanish researcher so frustrated with government’s disinterest, is taking his research a step further. He’s developing a test kit akin to a pregnancy test so inspectors can verify the species within minutes. But he said if governments don’t take the lead, he encourages consumers to speak up.

“I hope that if there are complaints, agencies will start answering them,” he said. “If companies know they’re not being monitored, what they’re going to do is try to make more money.