TRANSNATIONAL REPRESSION

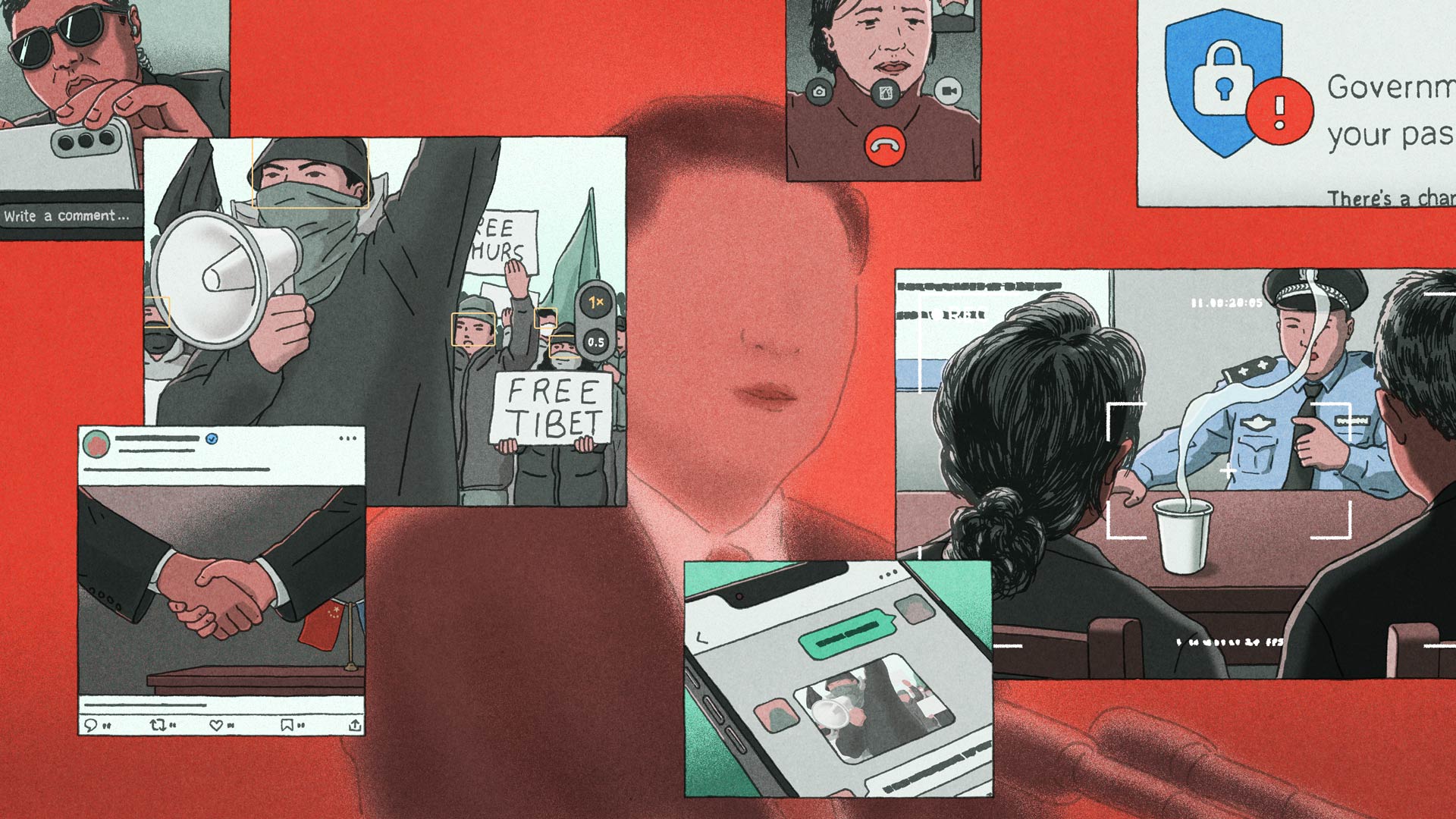

A film festival silenced — and the global reach of China’s repression

The abrupt cancellation of an independent Chinese film festival in New York reveals how Beijing and its proxies increasingly pressure critics abroad — a pattern documented by ICIJ and now drawing alarm at the United Nations and the European Parliament.

When filmmakers started calling Zhu Rikun in late October to pull out of an independent Chinese film festival he was organizing in New York, he initially thought the problem could be solved by reshuffling the schedule.

Zhu soon realized that the festival — set to launch just a week later — could not take place at all.

Thirteen Chinese filmmakers abruptly cancelled their trips. Zhu received requests to pull most of the 45 films on the program, including works without an explicit political message: A documentary following a Beijing couple whose child has leukemia; a fictional film about a woman who lost her job during the Covid-19 pandemic; and a feature about a middle-aged couple talking while on a long walk.

“In the end, I found that as long as the film festival continued, many people were still being harassed,” Zhu told the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Independent film festivals in China are often targeted by local authorities. But this time it was different, Zhu said, because it required reaching beyond China’s borders. “Their message was quite clear: They wanted to stop the film festival from taking place.”

Their message was quite clear: They wanted to stop the film festival from taking place.

— Zhu Rikun, director of the IndieChina Film Festival in New York

From international hubs like New York City and the United Nations’ premises in Geneva, to smaller towns in the United Kingdom and Australia, Chinese and Hong Kong authorities — and their proxies — continue to coerce, control or silence critics of the regime and independent voices who sought refuge overseas.

This phenomenon, often described as transnational repression, is expanding, according to recent reports by the U.N. and European Parliament, which identify China as a leading perpetrator alongside Russia, Iran and other autocratic states.

Earlier this year, ICIJ’s China Targets investigation exposed the sprawling scope and terrifying tactics of Beijing’s campaign to target regime critics living abroad. In collaboration with 42 media partners, the investigation uncovered how the Chinese government has misused international institutions, including the U.N. and Interpol, to target overseas dissidents, while democratic nations often do little to stop it.

In the weeks and months following the investigation, officials in democratic nations have announced reforms, saying the phenomenon amounts to foreign interference and presents a growing threat to their countries’ sovereignty.

In April, the U.N. published its first-ever guidelines on transnational repression. In November, the European Parliament followed up with a resolution urging EU member states to confront efforts by authoritarian regimes to coerce, control or silence dissidents living in Europe.

This month, at an event on transnational repression at the parliament in Brussels, European lawmakers and other officials, including representatives of the U.N.’s High Commissioner for Human Rights and the European External Action Service, the EU’s diplomatic branch, expressed concern about the growing threat.

“It is a global and urgent challenge that demands a global and urgent response,” said Christina Meinecke, OHCHR’s representative in Europe, echoing other officials who urged cooperation among democratic countries.

Germany, which has recently convicted a Chinese businessman and purported dissident for spying, is considering amending its criminal law to better address transnational repression, a foreign ministry official said at the event.

But response to the threat remains uneven, critics claim, with too few concrete actions.

Human rights advocates attending the event welcomed the attention to the issue by the EU and other international organizations but argued that it’s not sufficient to protect targets.

“Indeed the attention is growing,” said Philippe Dam, advocacy director at Human Rights Watch.

“That should not hide the fact that the EU’s response, foreign policy response, remains too limited, while the domestic responses remain quite inexistent.”

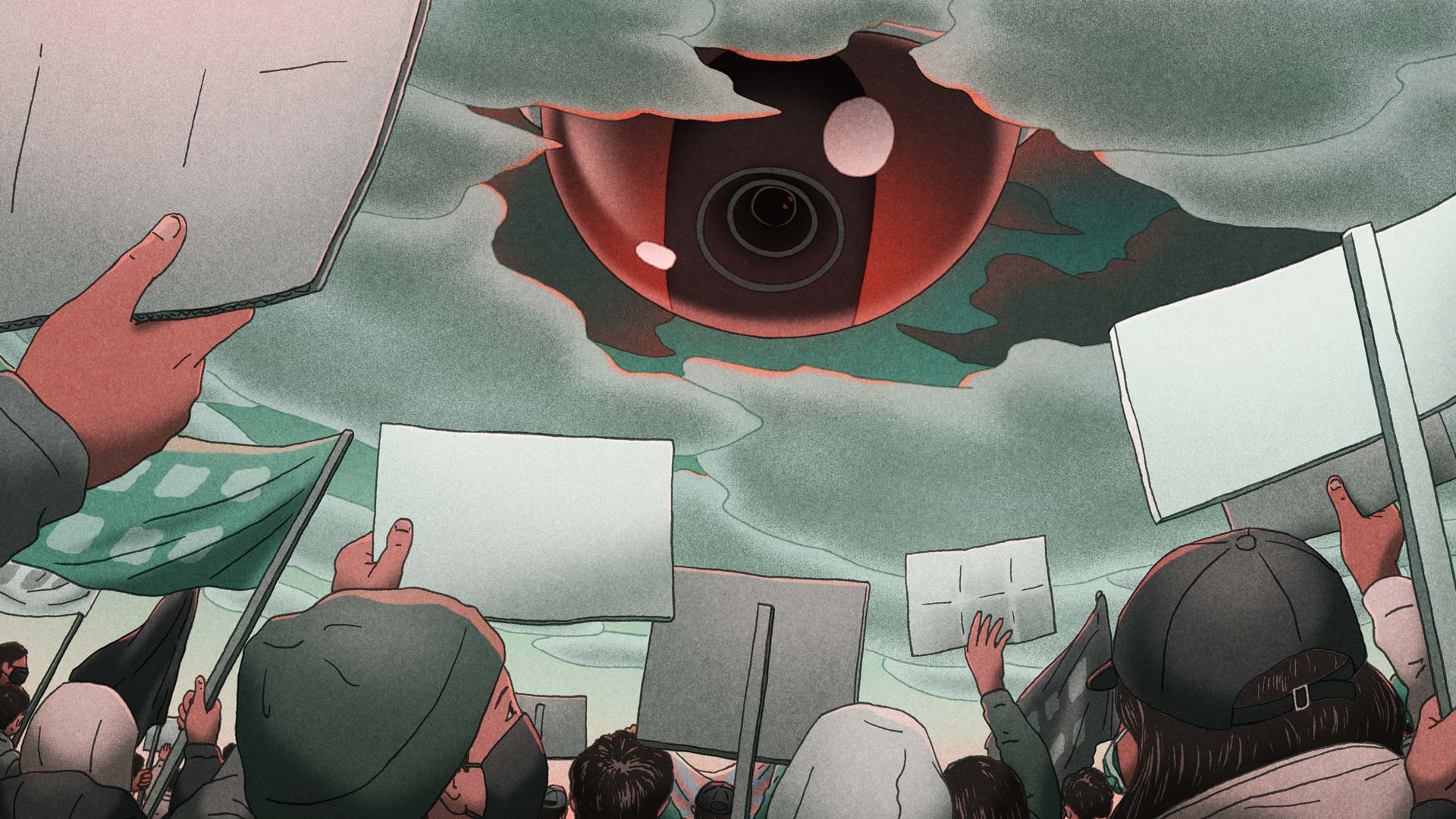

In recent months, at least two Europe-based Chinese students — Zhang Yadi, a Tibetan rights activist residing in France, and Hu Yang, in the Netherlands — were detained after they returned to China for the holidays on charges of “secession” and “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” respectively, allegedly for speaking up against the regime. According to human rights associations, the incidents indicate that they had been under surveillance by Chinese authorities while living overseas.

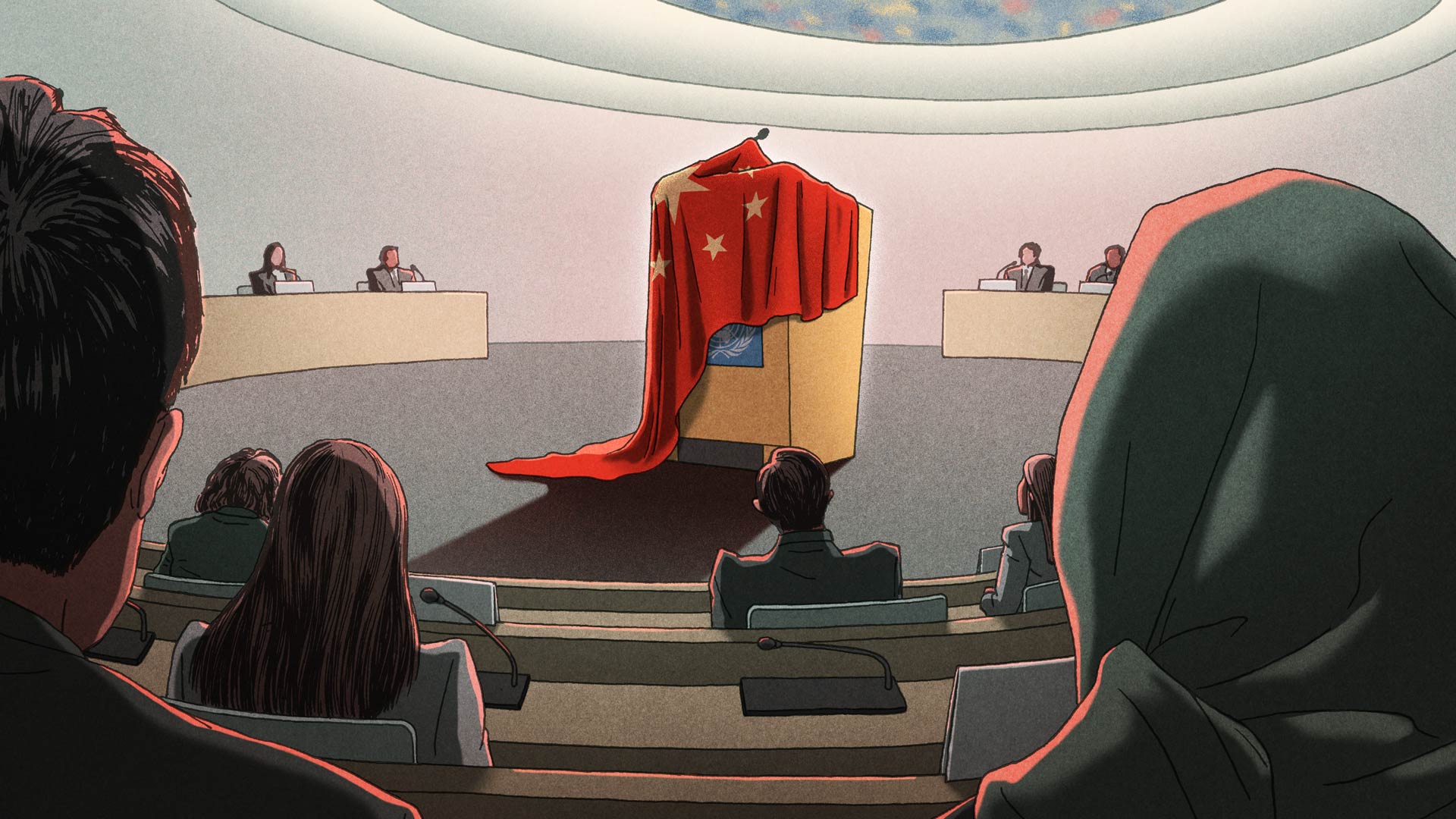

A Chinese spy at the U.N. mission?

Despite the U.N.’s calls for an urgent global response to the threat of transnational repression, the organizations’ own premises are not safe either, advocates say.

ICIJ’s China Targets investigation found that Beijing transformed the U.N.’s Palais des Nations in Geneva into a hostile environment for critics of President Xi Jinping. Human rights activists and lawyers told ICIJ they had been surveilled, harassed or intimidated by people they believe to be Chinese diplomats or government proxies, including delegates from nongovernmental organizations, inside the Palais and in Geneva at large. U.N. officials have also reported activists and lawyers being threatened with physical assault, rape and death.

Some activists said their family members, who they believed were pressured by Chinese authorities, asked them to stop speaking out.

ICIJ also found that more than half of the 106 Chinese nongovernmental organizations that were granted special “consultative status” by the U.N. aren’t independent of the government or the Communist Party.

A new documentary by Yle, a Finnish broadcaster and ICIJ media partner, appears to confirm ICIJ’s findings about some of China’s tactics at the U.N.

Yle found that a Chinese military spy worked as a high-ranking official with China’s U.N. mission in Geneva before allegedly trying to obtain NATO secrets from an Estonian scientist.

The agent, identified in court records as a member of China’s Central Military Commission’s intelligence bureau named “Victoria,” was listed as the second secretary of China’s Permanent Mission between 2012 and 2014, U.N. records examined by Yle show.

About two years after ending her U.N. stint, “Victoria” was part of a team of agents who, operating under the cover of a think tank, allegedly tried to obtain secret information about cybersecurity and maritime strategy in the Baltic Sea and Arctic regions, according to Estonian prosecutors.

The revelations emerged from a case involving an Estonian legal professional convicted of helping “Victoria” and two other Chinese spies connect with a marine scientist who had access to classified information while serving on a scientific committee of the NATO Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation in La Spezia, Italy.

The Chinese officers allegedly paid the scientist and the lawyer more than $40,000 in cash, luxury trips to Asia and dinners at Michelin-starred restaurants, according to court records. The scientist was convicted of espionage in 2021. The lawyer was convicted in 2023. The Chinese agents, who were based in Beijing, according to the records, were not prosecuted.

Yle found “Victoria” ’s Chinese name and identified the officer in the U.N. annals listing representatives of countries’ missions in Geneva.

The findings indicate that the officer had likely been working for China’s intelligence services all along, even while appearing as a career diplomat in Geneva, experts told Yle and ICIJ.

According to Nicholas Eftimiades, a retired U.S. intelligence officer with knowledge of Chinese intelligence operations, the case confirms the U.N. as “a hub” for spying activities.

“Chinese intelligence officers have been documented operating in international organizations for decades,” Eftimiades told ICIJ. “In no way is the United Nations a safe space from espionage.”

The agency and the Chinese Permanent mission did not respond to ICIJ’s comment requests.

Need for action

Zumretay Arkin, vice president of the World Uyghur Congress, an NGO often targeted by Beijing for their advocacy on Uyghur rights, said she was not surprised to learn that a Chinese military spy had likely worked at the Chinese mission to the U.N.

“We’ve been followed by Chinese diplomats from the mission itself,” Arkin told ICIJ. “They’ve taken our photos, and our family members were retaliated against because of our presence in that [U.N.] space and our work, and people from the mission themselves were responsible for that.”

In one case earlier this year, Arkin said a Xinjiang camp survivor discovered that police had allegedly intimidated his sister and mother in China at the same time that he was testifying at the U.N. in Geneva. In another incident just last month, Arkin said that pamphlets on Uyghur forced labor were “mysteriously removed” from her exhibition table inside the U.N. building. U.N. authorities told her they are investigating the matter.

While she welcomed the agency’s recent guidelines on transnational repression and its overall commitment, Arkin said victims expect bolder actions and “more bravery” from democratic institutions engaging with Beijing.

Transnational repression is “a reality that we’ve lived for many years” and it’s also “contributing to the shrinking space for civil society,” Arkin said. “We need to see concrete action, concrete protection … steps taken by the U.N., not just policy briefings.”