Data methodology

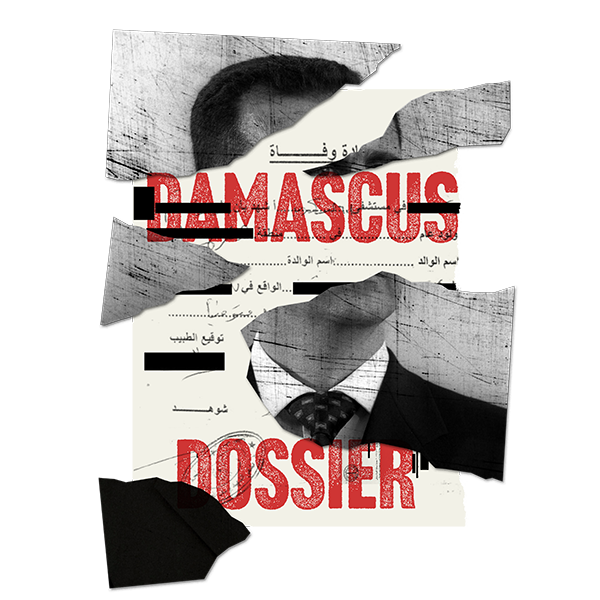

Inside the Damascus Dossier: From leaked images to verified data

ICIJ and its partners organized and analyzed thousands of chilling photographs to assemble comprehensive victim lists and quantify the human toll behind a sensitive data leak.

One year after the fall of former Syrian president Bashar Assad, a new leak shines a light on the brutality of Assad’s rule and the lengths his regime took to catalog the bodies of those killed during his last decade in power.

The Damascus Dossier is an investigation based on a cache of more than 134,000 records obtained by German broadcaster NDR and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 24 media partners. The leak contains the largest photographic archive of bodies of Syrian detainees who died between 2015 and December 2024 — more than 10,200 bodies in 33,000 photographs. This is how ICIJ and its partners arrived at those figures.

The Syrian civil war began in 2011 following the Arab Spring protests and ended on Dec. 8, 2024, when the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham militia toppled Assad’s government, leaving Assad and his top officials to flee to asylum in Russia. At least 160,000 Syrians were arrested and disappeared during those 13 years.

The chilling archive of photos, taken inside Assad’s system of incarceration, includes images of thousands of bodies, nearly all men and what appear to be a few teenage boys. A cross-border team of reporters and editors reviewed hundreds of these images and found that the bodies were mostly naked, emaciated and appeared to have been abused, lying on the floor, and sometimes covered in flies or fly droppings. Some appeared to have been starved to death; others likely died under torture. All died at the hands of Assad and his functionaries. The dead included at least one newborn.

Stripped of their dignity even in death, prisoners were also stripped of their names, reduced to a detainee number visible on white labels usually placed on their chests or foreheads.

Counting the dead

As part of the investigation, members of the ICIJ technology and data teams received a dataset of folders containing photos. To assess how many people were among those photographed, the data team analyzed the folder structure, as each folder was organized by year, then month, then day and photographer. Each directory within the dataset shared with ICIJ was named with Arabic characters and numbers representing the detainee numbers assigned to each victim. Some folders were named with a single detainee number; some with several detainee numbers, and some had more than a dozen detainee numbers in a single folder name.

ICIJ’s data team mapped out the file paths from the dataset. Reporters separated out the year folders, then the months, then the folders containing the detainee photos. They then created a list of the long Arabic folder names and put them into a spreadsheet. Once the team translated the folder names to English, they included all those labeled “detainees,” or “detainee,” eventually arriving at the figure of more than 33,000 detainee photographs.

The data team then analyzed the photos and manually counted the detainee numbers in each folder name. That process allowed us to determine that the photographs in the leak contained more than 10,200 bodies, 70% of which were dated from 2015 to 2017.

This dataset was different from any other ICIJ has received in its 25-year history. The challenges were emotional as well as intellectual.

Such work has a cumulative effect. One member of the data team, having seen thousands, reached a point at which she could not bear to look at any more.

The images “burn themselves into your mind,” said Benedikt Strunz, an investigative reporter and editor at NDR. “Because you see things in them that shouldn’t really exist.”

Analyzing the contents of the images

Twelve journalists from ICIJ, NDR and Süddeutsche Zeitung agreed to examine and analyze a random sample of the photographs of the bodies to provide deeper insight into the trove of images. Prior to the analysis, the journalists participated in an online training session to prepare themselves to report on potentially traumatic content.

To have a representative statistical sample, ICIJ’s data team selected 540 of the 33,000 photographs using the RAND Excel function created for that purpose. This sample size allows for a 98% confidence level that what the journalists saw in the sample set could be fairly used to describe the photos in the entire dataset.

Journalists accessed the photos in a folder marked “sensitive” on Datashare, ICIJ’s secure data platform, where each image was overlaid with a warning message. Each journalist checked an assigned list of photos and filled out a questionnaire designed with the help of a forensic expert. This provided a uniform dataset of what they saw in the photos, for example: whether a person was naked or clothed; what surface their body was on; whether there was a shroud or a body bag; if they showed signs of starvation; whether their body or face showed signs of physical violence, and, if so, what kind; and if a piece of white card, often displaying an identification number, had been placed on top of their body, or if one had been added to the photo.

Working in a shared online spreadsheet, reporters did a primary check of the 540 selected photos. A different journalist then reviewed each photo again. That system was designed to limit the number of photos each reporter analyzed. Finally, a third and final check was done to resolve any differences. The results showed that almost half of the bodies were naked, while three out of four bodies lay on a floor — sometimes on a metal surface, without a body bag, blanket or a shroud.

Nearly three-quarters of the bodies showed signs of starvation. This stood out as one of the most prevalent conditions captured in the images. Two-thirds had evidence of physical harm, such as bruises and lacerations. More than half included injuries to their face, head or neck — most often blunt-force trauma, but some showed evidence of cuts or stab wounds.

Almost all of the photos included a white card — either placed on the body, nearby or later added to the image — displaying the detainee’s number and noting that Assad’s security forces were responsible for their custody. Some victims were labeled with markings directly on their bodies. Photos rarely included the prisoners’ names.

Identifying victims

In hopes of helping families of victims find answers about their loved ones’ fate, ICIJ and NDR compiled lists of names from the records, where possible.

Using Arabic text in the cache of photos, along with death records, arrest reports and other records, journalists from ICIJ, NDR, ARIJ and Süddeutsche Zeitung extracted more than 1,500 names, including 454 names of people who died in detention and 1,099 names of people who were arrested. Journalists also examined hundreds of pages of arrest records and extracted the prisoner’s name, place of birth, mother’s name, year of birth, the military branch responsible for the arrest and arrest date in Arabic and translated this data to English. Then an Arabic-speaking reporter from Süddeutsche Zeitung fact-checked the translations.

From the cache of photos the project team was able to build a list of 323 names. NDR reporters used Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology to extract Arabic text from a selection of white text boxes superimposed on the images or sheets of paper placed over the bodies. Using those results, the ICIJ data team translated the text into English and extracted as many names as possible. Arabic-speaking journalists helped to fact-check our results.

To help victims’ families in their search for missing loved ones, ICIJ prepared lists of detainees’ names from the photos and other Damascus Dossier records; NDR then shared the list with the following four entities: the United Nations’ Independent Institution on Missing Persons in Syria; the Syrian Network for Human Rights; Ta’afi, an initiative that provides resources to Syrian victims of detention and torture; and the Syrian Center for Legal Studies and Research, a German NGO that works to expose Syrian human rights violations and defend victims.

The Syrian Center for Legal Studies had obtained the photos independently, as have German prosecutors, who have been at the forefront of prosecuting crimes against former members of the Assad regime.

Contributing reporters: Benedikt Strunz, Sulaiman Tadmory, Volkmar Kabisch (NDR), Hannah El-Hitami, Lena Kampf, Lea Weinmann (Süddeutsche Zeitung), Denise Ajiri, Agustin Armendariz, Jesús Escudero, David Kenner, Delphine Reuter, Nicole Sadek, Fergus Shiel (ICIJ)