Arriving in Diriamba, Nicaragua, cameraman Ricardo Salgado was greeted by menacing scenes following the brutal government crackdown of a local uprising.

“Paramilitaries and hooded police were already there,” Salgado recalled. “Even the police were covering their faces.”

Cardinal Leopoldo José Brenes Solórzano and two bishops were leading a delegation seeking safe passage for protestors opposed to Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega.

The protestors had taken refuge in the San Sebastian church after they were assaulted by state security forces and government supporters — in the midst of nationwide clashes that resulted in the deaths of 31 protesters, four police officers and three government supporters.

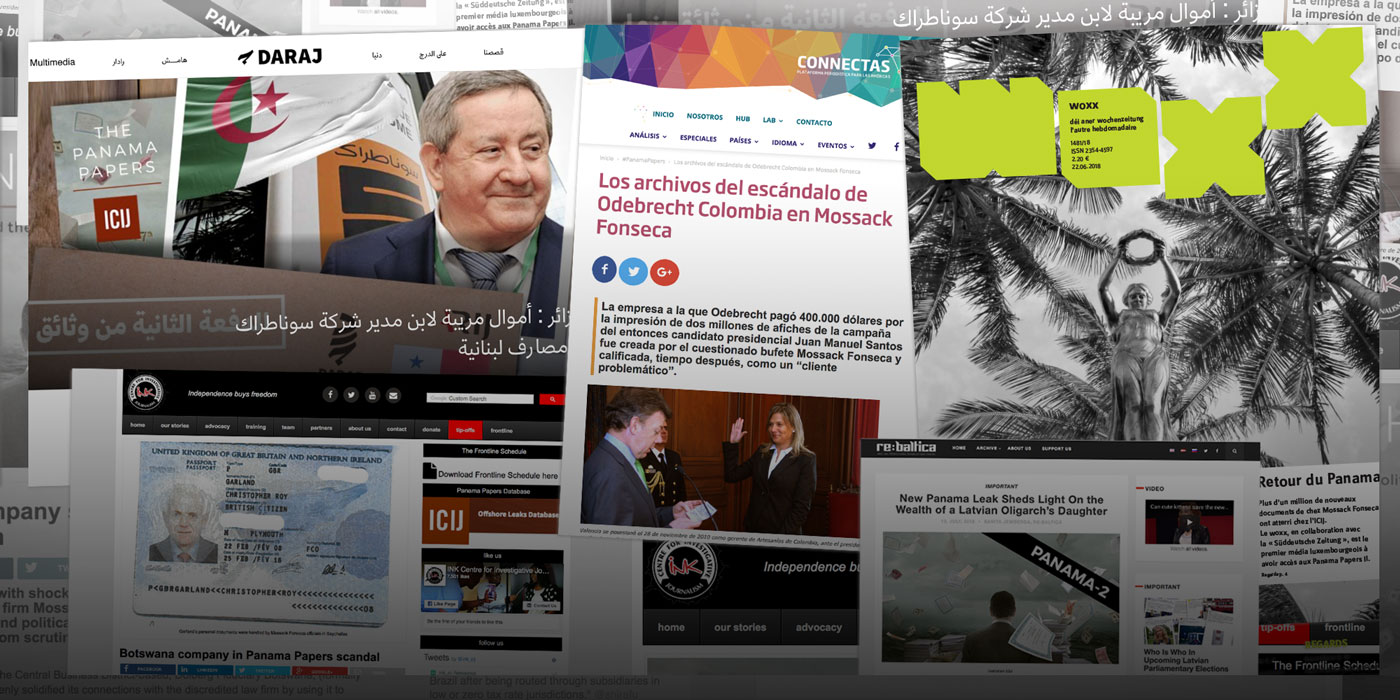

Salgado was there to capture the moment for Confidencial, a leading Nicaraguan news program headed by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists member Carlos Fernando Chamorro.

It was a very terrible situation… I was in the mouth of the wolf

As Salgado’s camera rolled, the paramilitaries forced their way into the church alongside the rescue delegation. Some were armed with machetes and shouted insults at the churchmen, calling them “killers” and “sons of whores.”

Then, Ortega’s fighters set upon the clergymen as they tried to leave the sanctuary. They rained blows on priest Edwin Román and slashed bishop Silvio Baez, leaving him with cuts across his arm.

“For me there is not even a name for that,” Salgado said. “It is a direct war against the Catholic church.”

Realizing the events were being recorded, the fighters turned violently on Salgado and the other journalists. They punched Salgado in the face twice and stole his video camera. Fearing that Ortega’s men would start shooting, he fled nearby on foot.

The cameraman hid for two hours in the home of a local man who offered him refuge, as paramilitaries roamed the streets surrounding the church in Toyota Hiluxes, searching for protestors and journalists.

“It was a very terrible situation,” Salgado said. “I was in the mouth of the wolf, as we say in Nicaragua.”

The following day, July 10, Confidencial released a video with dramatic footage of the confrontation at the church – compiled in large part from numerous other Nicaraguan outlets whose equipment was not seized.

Foreign media, including the BBC and Associated Press, also covered the assault on the clergy. Their equipment was returned to them after the attacks, according to Salgado.

The incident reflects a remarkable pattern that Salgado’s boss Chamorro says is unfolding in Nicaragua: as the regime’s repression grows increasingly brutal, the media has become more and more independent.

“The media independence that exists now in Nicaragua was not a gift,” Chamorro said. “It was won by journalists and the people.”

Since this spring, Nicaragua has been in a state of upheaval. Massive protests in April against a government plan to reduce social security benefits sparked a wave of violent repression by the Ortega regime.

Human rights groups say that nearly 450 people have been killed, mostly by state security forces and government-allied paramilitaries, and a military crackdown in July cemented Ortega’s control of the country.

Ortega has been president of Nicaragua since 2007. He first came to power in 1979 as leader of the leftist Sandinistas but, in his second stint in power, has suppressed civil liberties, abolished presidential term limits, cut social services and won support from the business community.

One result of the current wave of state violence is that reporters are now working together with greater solidarity across media outlets, Chamorro said. As a security measure, his reporters now travel in groups of at least three that include journalists from other outlets.

Foreign journalists provide an additional measure of protection. In the community of Monimbó, an indigenous neighborhood in the city of Masaya, locals barricaded the streets until they were violently driven out by police and paramilitaries.

Confidencial editor Carlos Salinas Maldonado gained access shortly after the crackdown together with The New Yorker’s Jon Lee Anderson. Salinas wrote a lyrical dispatch about how the occupied city had quietly “closed its doors and resisted,” including burying the protesters killed by the military after a somber procession through the empty streets.

“This is not a war between two armed groups,” Chamorro said. “It’s a massacre.”

The regime’s brutality has reduced its popular support and prompted more media outlets to cover its abuses, Chamorro said. He said the country’s most widely watched network, Canal 10, was largely uncritical of the Ortega regime prior to the recent upheaval. But the severity of the government’s violence and the insistence of Canal 10 reporters on covering the reality has brought about a major shift in its coverage.

Mauricio Madrigal, the news director for Canal 10, said his station had significantly increased its political coverage and was determined to hold the government accountable.

“We have a social commitment to inform the people at this historic moment for our country,” Madrigal said.

Chamorro said Confidencial’s coverage during what he described as a gradual eleven-year shift from democracy toward authoritarianism during Ortega’s rule had earned the outlet additional authority for its reporting of the current crisis.

“We are now reaping the credibility we have sowed for 11 years,” Chamorro said.