SOLITARY VOICES

‘Solitary Voices’ detainee wins big, but remains in immigration limbo

Now a World Poker Tour champion, Ilyas Muradi still faces the threat of deportation after spending more than two years in immigration detention, including months in an isolation cell.

With a bandana-style face mask pulled up over his nose, and a black Los Angeles Raiders cap shading his eyes, the poker player’s face was almost totally obscured. So I concentrated on his words. “Let’s gooooo,” he shouted, jumping from the table and high-fiving an onlooker after winning a crucial hand.

It was a voice I recognized, but heard in a situation that seemed totally improbable.

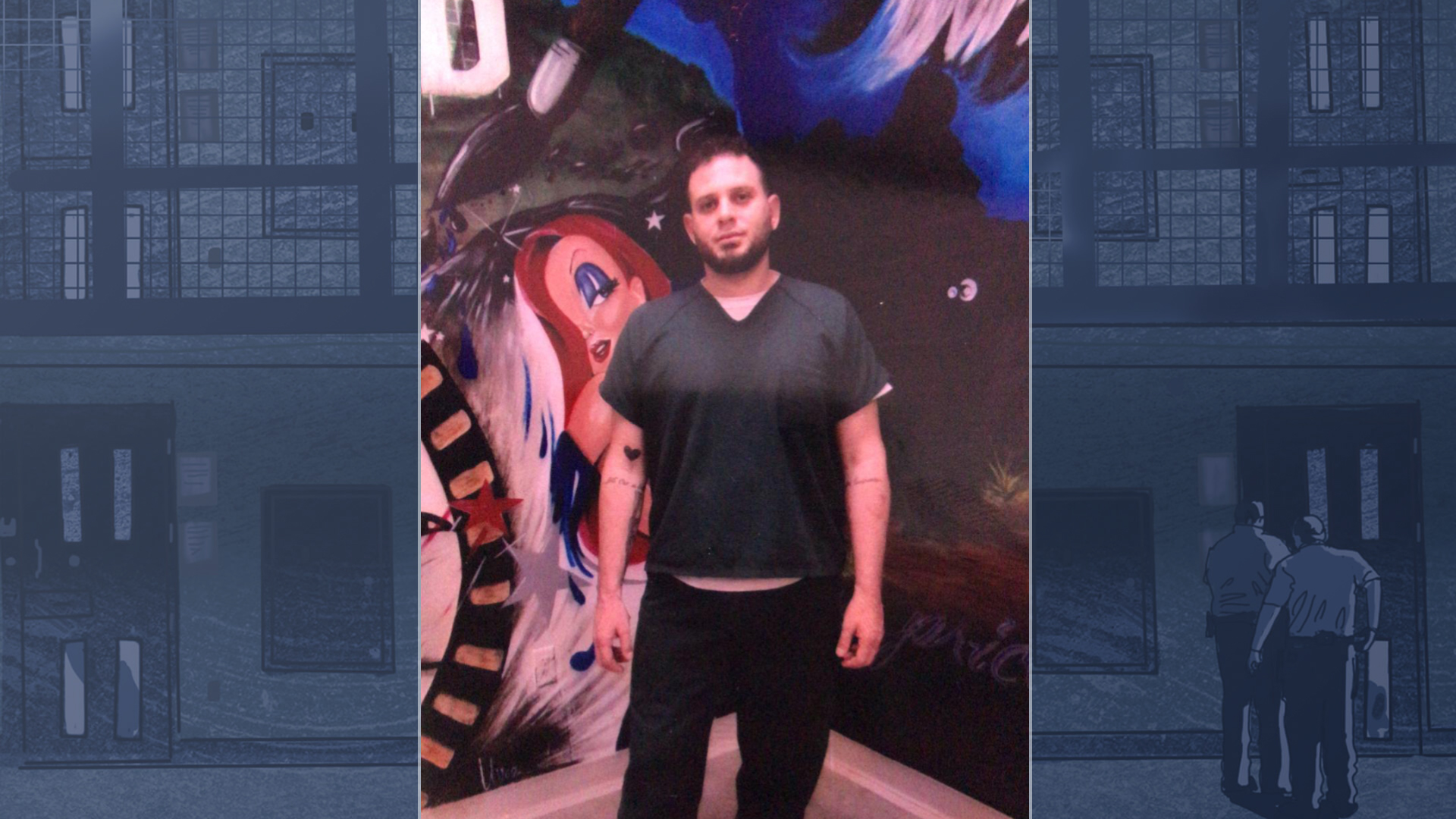

Ilyas Muradi is a 32-year-old Afghan immigrant. When I last spoke with him, in March 2019, he had languished for more than a year in a Texas immigration detention center while the U.S. government tried to deport him. He had spent most of the previous four months confined to a tiny isolation cell battling loneliness, dread and despair.

Muradi’s case would feature in Solitary Voices, an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists into the abusive use of solitary confinement by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. Extended stays in isolation are analogous to torture, according to the United Nations.

Muradi desperately wanted to return home to Indiana to his wife and children. But that seemed unlikely. He was steeling himself to be deported to Afghanistan, which he hadn’t seen since he was a child, and where he feared he’d be killed. “It’s like I woke up in a nightmare,” Muradi told me at the time.

Two years after that conversation, I got an email from an official at the World Poker Tour, which runs high-stakes tournaments across the world. He wanted to confirm: was the Ilyas Muradi in the video the same person I had interviewed from solitary confinement?

LET’S GOOOOOO 💪💪💪 pic.twitter.com/5dmgy6nCQB

— World Poker Tour (@WPT) January 27, 2021

It was. Muradi had shot out of obscurity to beat more than 1,500 contestants to win a national championship. His prize came to $620,000. “This is amazing, it’s making me want to cry,” Muradi said to the camera. “Anyone’s dream can come true.”

The victory stunned the poker world. It was the first national tournament Muradi had ever entered. “Almost everyone who comes to these events has some kind of previous success,” Matt Savage, the World Poker Tour’s executive tour director, told me. “This is not really heard of.”

Muradi’s story is a rare positive outcome for the dozens of immigrants I interviewed for Solitary Voices. But to characterize it simply as a tale of perseverance and luck would overlook a great deal: lost years, lost time with family, lost income, trauma — and still, even now, the possibility of deportation.

Muradi was released from ICE custody because Afghanistan had no record of him living there and could not claim him as a citizen, according to his immigration attorney. As it stands, Muradi is a citizen of no nation: Stateless, he doesn’t have a passport and remains stuck, as he has since he was a child, in immigration limbo.

Stateless in solitary

Muradi was born in Afghanistan as the country was moving from a brutal war with the Soviet Union to a devastating civil war. When he was four years old and shortly after his father was killed by a bomb, his family fled the country, he says. “It was a war zone, they were attacking our neighborhood,” Muradi told me. “We were lucky to leave to save our lives.” The family first went to Pakistan, and, in 2001 they settled in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

In 2007, Muradi was charged with selling marijuana to a police informant. The sale happened when he was 16 or 17, and involved marijuana he had bought for his personal use, according to court filings by Muradi’s attorney. The subsequent conviction would cause years of hardship.

After serving a short sentence in state prison, he was detained by ICE and held in detention for several months. Muradi started playing poker as a way to pass long days with fellow detainees, he says. It quickly grew into an obsession. “Once I learned, it was so interesting that I never wanted to stop learning,” Muradi says.

After he was released, he scoured YouTube for poker stars. “I’d watch all their videos, watching how they play, how they win.” In his 20s, he played with friends at local events and sometimes with people he met along the routes he worked as a long-haul trucker. “Whenever I had any chance to play, I was playing,” Muradi said.

In August of 2017, while driving through Texas on a trucking route, Muradi went to Mexico to hit some bars with a few other truckers. He had a green card and thought nothing of re-entering the country. But U.S. authorities detained him at the Laredo border crossing, citing his prior drug conviction. “They just told me that there’s a ‘red flag’ on my record. They said that I had just self-deported to Mexico,” Muradi told me.

When Muradi spoke with ICIJ in 2019, he had spent most of the preceding four months locked in a tiny solitary confinement cell at ICE’s South Texas Detention Complex in Pearsall, Texas. He said he was accused of entering a shower without authorization, and threatening a guard.

Muradi denies that he threatened a guard, but acknowledged having gotten into fights with other detainees. He said he believes guards had begun to punish him simply because they didn’t like him.

ICE did not respond to questions about Muradi’s case.

In May of 2019, Muradi’s attorney sent ICE a letter, pleading with the agency to release him from solitary confinement. “We believe this amounts to inhumane treatment and urge you to release him from isolation without delay,” the letter said.

Later that month, Muradi was released from solitary confinement and back into the general population at the detention center.

Meanwhile, he appeared to be losing his immigration case. The Trump administration frequently attempted to return asylum seekers to dangerous and war-ravaged countries. This aggressive approach posed practical problems for deportation agents. The previous January, a judge had found that — although there was no dispute that Muradi had no real connection to Afghanistan — Muradi had not provided enough evidence to establish that he would be in danger if he were deported.

Yet weeks and then months passed. Behind the scenes, U.S. immigration authorities were apparently struggling to arrange the paperwork for Muradi’s removal. The Afghan government said it had no record of Muradi living in the country and could not establish him as a citizen, according to Muradi’s lawyer.

Muradi was a citizen of neither his home country nor his adopted one.

Roughly 10 million people in the world are stateless, according to the United Nations. Many people become stateless after their country dissolves or because they are deliberately excluded from citizenship because of their ethnicity or religion. For others, like Muradi, paperwork or other administrative obstacles are to blame — a problem especially present for immigrants from countries mired in the chaos of prolonged conflict. Stateless people, as a group, are especially vulnerable to human rights abuses, the U.N. says.

The U.S. does not formally recognize people as stateless, including for purposes of immigration proceedings.

Detainees who fall into this gray zone are often released. That’s what happened, finally, to Muradi. On Oct. 30 2019, after more than two years in custody, he was allowed to return to Fort Wayne to live with his wife and two children. He began to look for work at trucking companies and in warehouses, he says. Once the pandemic struck a few months later, his job prospects tried up. “It became a whole new kind of struggle,” Muradi told me.

“I just survived longer than they did”

In January, Muradi flew to Seminole, Florida, site of the Lucky Hearts Poker Open, one of the country’s first in-person poker tournaments since the start of the pandemic. He could not afford to enter the main event, which comes with a $3,500 buy-in, but joined a so-called satellite tournament for smaller-time players. These ancillary tournaments cost just a few hundred dollars to join, and players face long odds of getting onto the main floor to play the pros.

But Muradi won over and over again. He was playing 12-hour days. He advanced from the satellite into the championship’s main room. He amassed a larger and larger pile of chips. He was playing against — and beating — poker stars he had watched on TV but had never seen in person. “I was really nervous,” Muradi said. “These were champions.”

As he advanced, the championship’s organizers at the World Poker Tour began to take note, and plugged his name into a database of previous poker champion entrants. His name did not appear in any previous game. “We were like ‘who is this guy?’” Savage, the World Poker Tour executive, said.

Muradi is hesitant to say he “beat” his numerous opponents, saying instead “I just survived longer than they did.” Eventually there was no one left to play. He had won the entire tournament. Muradi’s win that week vaulted him to fame in the poker world, with the World Poker Tour website declaring that he had risen from “Detention to Domination.” Muradi also won entry into WPT’s upcoming Tournament of Champions.

Surrounded by comically large trophies and stacks of poker chips, Muradi could hardly believe it. “If you want to get something you’ve got to go get it,” he said in a video released by the poker tour.

When I caught up with Muradi after his big win, he told me he hopes to buy his family a home with the earnings. He is considering launching his own trucking business — investing, perhaps, in smaller Sprinter-style trucks that he used to drive on cross-country routes hauling automotive parts.

He also expects to spend some of his winnings on immigration lawyers. Muradi’s wife and children are citizens, but he is fighting for permanent residency. “I need to get this off my shoulders.” Muradi says. “This is my country.”