In December 2024, criminals stole thousands of dollars from Steve Beckett at a Circle K convenience store in Indiana. The robbery happened in broad daylight.

The thieves didn’t use a gun or a knife. There was no getaway car. The instrument of the crime was a machine, much like an ATM, owned by Bitcoin Depot and placed in the convenience store as part of a nationwide agreement with Circle K.

Beckett, 66 at the time, had been paying bills at home when his computer froze and a message directed him to call what turned out to be a phony Microsoft service hotline.

On the phone, a man named “Josh” told Beckett that someone had hacked his computer and used his credit cards and bank accounts to purchase child pornography. Soon, Beckett was speaking to another man, who claimed to work at his bank, and then someone else, who said he represented the Federal Reserve. His life savings were at risk, the men said, and there was only one way to protect them: converting the money into bitcoin.

Over the course of two days, the men cajoled and threatened Beckett, warning him he could go to prison. He had spent years working in management at a casino and selling securities and felt something was wrong, but he was terrified.

“My heart was racing, my blood pressure’s going through the roof,” he said.

Panicked, Beckett withdrew $4,000 from his bank and, at the men’s direction, drove to a Circle K with a Bitcoin Depot ATM. Beckett had never bought bitcoin and knew little about it, but he didn’t ask too many questions. On the phone, one of the men walked him through how to deposit the funds. “I was shaking like a leaf,” he said. The next day, he deposited another $3,000.

The machine, often called a crypto ATM or bitcoin ATM, converted the cash into bitcoin and transferred it to a digital address the men provided. For completing the transaction, Bitcoin Depot received about $2,000 in fees.

Beckett lost every dime.

The machine at Beckett’s local Circle K was one of more than 8,000 operated by Bitcoin Depot in gas stations, grocery stores and other retailers across the United States. In a recent SEC filing, Bitcoin Depot said it had bitcoin ATMs in “approximately 750 Circle K stores” in the U.S. and Canada as of the end of September.

As crypto ATMs have multiplied — there are nearly 40,000 machines operated by companies worldwide, according to the online industry publication Coin ATM Radar — scams have proliferated alongside them. In 2024, the FBI received nearly 11,000 fraud complaints involving crypto ATMs, a 99% increase from the previous year. The complaints represented about $247 million in alleged losses. Those numbers are slated to rise even higher this year, with around $333 million lost to the same type of fraud between January and November 2025.

The surge has become a problem for the entire crypto ATM industry and raises questions about whether the retailers that host the machines are doing enough to protect consumers. Circle K’s deal with Bitcoin Depot is one of the largest collaborations between a retail chain and a bitcoin ATM operator in the world.

Circle K has made millions of dollars off the deal and continued the relationship even as complaints — both from customers and employees — have mounted, an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and media partner CNN found. In January 2025, Circle K extended its contract with Bitcoin Depot through mid-2026.

Since January 2024, more than 150 alleged victims have reported scams involving Bitcoin Depot machines at Circle K and Holiday gas stations — which are owned by Circle K’s Canadian parent company Alimentation Couche-Tard — amounting to at least $1.5 million in losses, according to an analysis of police reports, consumer complaints, court cases, news reports, and interviews done by ICIJ and CNN.

After police responded to a scam at a Circle K in Florida, a district manager was recorded on body cam footage telling the officers, “I hate these machines. I’d like to get them out of the stores.” The sentiment was shared by other Circle K employees in interviews with ICIJ and CNN. One manager, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, recalled how a victim returned to the store with a sledgehammer and tried to break open the machine and reclaim his money.

If we were to eliminate scams 100%, we would be hurting. — former Bitcoin Depot employee

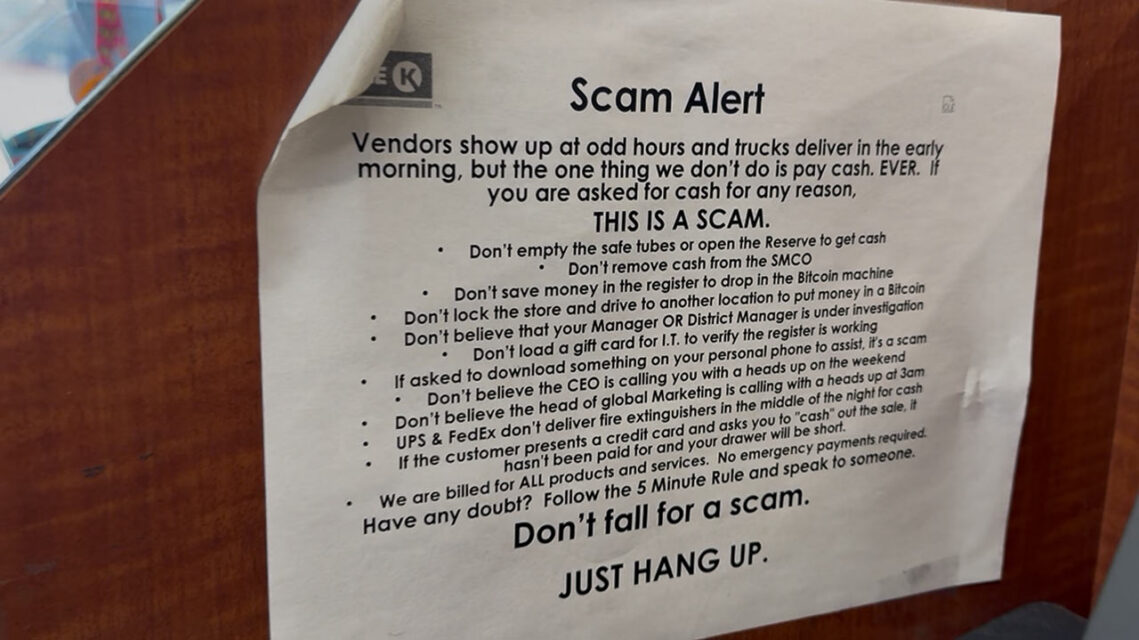

Circle K has warned its workers to be on the lookout for scammers; employees said management has sent emails about the problem and conducted training. In one Circle K in Indiana, a sign by the register warned clerks against depositing the store’s money into Bitcoin Depot’s machines.

In response to detailed questions from ICIJ and CNN, a Circle K spokesperson said that the company’s staff receive training on recognizing common scams, but the workers are not responsible for overseeing customer transactions on Bitcoin Depot ATMs, which are “owned and managed solely by third parties.” The company said it works closely with Bitcoin Depot “to ensure their services consistently meet our standards, regulatory requirements and customers’ needs and expectations.”

Bitcoin Depot said in a statement “the vast majority of our customers use our kiosks for legitimate purposes. Protecting consumers is central to our model, which is why we invest heavily in compliance, blockchain monitoring, scam warnings, and partnerships with law enforcement.”

The findings about Circle K and Bitcoin Depot are part of The Coin Laundry, an ICIJ-led cross-border investigation that exposes how cryptocurrency companies make money off the proceeds of scams, theft and other crimes — while those who’ve lost their savings or livelihoods are left with little hope of justice.

“If we were to eliminate scams 100%, we would be hurting,” according to one of several former Bitcoin Depot employees who asked for anonymity to discuss the company.

In a lawsuit against Bitcoin Depot filed in early 2025, Iowa’s attorney general wrote that an analysis of transactions conducted in the state on the company’s machines between October 2021 and July 2024 suggested that more than half involved scams.

Authorities have also accused other crypto ATM industry leaders of facilitating high levels of scam transactions. About 90% of transactions on the CoinFlip ATM network examined by Iowa’s attorney general were scam-related, according to court filings. And prosecutors in Washington, D.C., drew similar conclusions about transactions in their jurisdiction made on machines operated by Athena Bitcoin. The companies are the second- and third-largest ATM operators, respectively, according to Coin ATM Radar.

A CoinFlip spokesperson told ICIJ that the company invests heavily in preventing scams and fraud. Athena did not respond to requests for comment. In court filings, Athena Bitcoin said that it was a “neutral intermediary” that is not liable for abuse of its system by criminals.

Industry representatives say that their customers buy bitcoin to send to family abroad, make online purchases and as an investment, among other reasons. Some critics of the machines, however, question whether they are useful for anything other than money laundering and scams.

“When we talk to Bitcoin Depot and we talk to these other places, they’re insistent that their ATMs are investment machines, that they’re for people to make legitimate investments,” Gerard Lotz, a police detective in Louisiana who has investigated many scam cases involving the company, said in a recent interview. “Yet, I don’t know any investment firm anywhere that charges 30%.”

In 2024, Bitcoin Depot collected between 15% and 50% of each transaction made through its ATMs, according to corporate filings. Its relationship with Circle K accounted for nearly a quarter of its revenue that year.

That’s how we were living. Paying for things, paying for bills, paying for our mortgage, buying our daughters stuff for their birthdays for Christmas. We can’t do any of that. — scam victim Steve Beckett

For Bitcoin Depot and Circle K, the $7,000 Beckett lost isn’t even a rounding error on their annual earnings. But for the Indiana senior, who is an ordained minister and volunteer firefighter, the funds meant security.

“That money was our livelihood,” he said. “That’s how we were living. Paying for things, paying for bills, paying for our mortgage, buying our daughters stuff for their birthdays for Christmas. We can’t do any of that.”

Both the crypto ATM companies and the stores that host them need to be held responsible, Beckett said. He is suing Bitcoin Depot as part of a lawsuit, one of at least three aimed at the industry’s major player.

Bitcoin Depot has denied any wrongdoing, saying that it “cannot be held liable for the criminal acts of third-party scammers, especially considering the robust warnings and safeguards provided” on its machines and during transactions. In February, a federal judge sent one of the cases, which also included allegations against Circle K, to arbitration.

Circle K is not named in Beckett’s suit, but he still believes the retail chain shares responsibility for what happened to him and others.

“I think they do know what’s going on,” he said. They’re “reaping the benefits of having the machine in there and making the money from it.”

‘The biggest deal’

From the early days of the crypto ATM industry in 2013, the machines were largely hosted at small, independently owned businesses such as liquor stores, gas stations and corner groceries.

Bitcoin Depot’s founder and CEO, Brandon Mintz, installed the company’s first ATM in 2016 at a vape shop in Atlanta.

Mintz’s pitch to retailers was simple: Businesses would get a monthly payment and increased foot traffic. Customers would get convenience and privacy.

The company was also selling trust, Mintz believed. People were understandably suspicious of exchanging cash for virtual currency, he said at an Atlanta bitcoin conference in 2019. But that would change “once you have a physical machine sitting somewhere next to an ATM that you’ve used all the time at a store you always go to,” he said.

In the summer of 2021, with bitcoin rapidly becoming mainstream, Bitcoin Depot and Circle K signed an exclusive agreement, a major step toward achieving Mintz’s vision.

“It was the biggest deal and remains the biggest deal in that space,” according to a former Bitcoin Depot employee.

With the deal, Circle K became “the first major retail chain to deploy Bitcoin ATMs within its stores,” Bitcoin Depot said in a press release.

That gave the chain “an important, early presence in the fast-growing cryptocurrency marketplace,” Denny Tewell, a Circle K senior vice president, said in the release.

The agreement with Bitcoin Depot was lucrative for Circle K, which was initially paid as much as $700 a month in rent per machine, according to two people familiar with the payment system and notes reviewed by ICIJ.

With more than 6,300 stores in the U.S. alone, Circle K represented a potential goldmine for Bitcoin Depot. By the end of 2021, the convenience chain’s stores accounted for over 20% of the company’s transaction volume.

Bitcoin Depot also gained something potentially even more valuable than increased revenue: the opportunity to move the business to locations with high name recognition.

Problems soon surfaced, however, as store managers began reporting issues with scams involving the machines and asking Bitcoin Depot for guidance, according to two people familiar with the situation.

Scams and money laundering had been a problem since the crypto ATM industry’s early days. In a 2018 post on its website, Bitcoin Depot warned that it had “stopped fraudsters that use many different scams to steal, and new routines are used daily.”

Seeking to protect customers and reduce their own liability, crypto ATM operators placed scam warnings on machines and increased network monitoring. Bitcoin Depot’s 2019 compliance handbook required employees to keep detailed records of known scams that occurred on its ATM network and, when cases topped $2,000, send a suspicious-activity report to the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, according to a copy obtained by ICIJ. The company would blacklist known scammers and close victims’ accounts.

Still, the problem continued to grow, and by 2021 crypto ATMs had become the preferred tool for tech-support and government-impersonation scams — the same kind that targeted Beckett — according to Mike McGillicuddy, a special agent at the FBI who specializes in financial crimes and led a task force aimed at recovering scam victims’ funds.

Scammers favor the machines over other methods because there is no need to use intermediaries, he said, explaining that “the money can instantaneously be put into a wallet under their control and transferred overseas,” where it is beyond law enforcement’s reach.

To buy and sell cryptocurrency, you need to use a digital wallet. Crypto wallets have public and private keys. The public key is similar to a bank account number, while the private key is more like a password. Whoever holds the private key controls the cryptocurrency linked to it.

Most centralized cryptocurrency trading services, or exchanges, provide users with a deposit wallet that they host. This means that the exchange holds their private keys, and users must instruct the exchange about what to do with their cryptocurrency.

With unhosted wallets, users hold both the private and public keys, and are the only ones who can access their wallets.

The prevalence of scams made it clear that the industry needed to reform itself, according to Marc Grens, whose business DigitalMint operated a nationwide network of the machines for nearly a decade.

Grens tried to establish an industry group to self-regulate the machines and improve compliance standards. But other ATM operators weren’t interested, he said. Ultimately only one other company joined his campaign. Today, both DigitalMint and that company have abandoned the business.

Grens concluded it was impossible to remain profitable without facilitating scams. The more money his company spent on fraud prevention, the more fraud it found, he said. When it came to the largest transactions on the network, “95% of the customers you end up talking to were victims,” he said.

Moeses Streed, who worked at Bitcoin Depot’s customer service hotline in 2021, said 40% of the calls he received on any given day would be scam-related.

“Some days it would be the only call you would get,” he said. “The job felt more like live scam prevention than customer service.” (Bitcoin Depot told ICIJ that it does not agree with this description.)

Nevertheless, marketing materials on Bitcoin Depot’s website assured potential ATM hosts that the machines would create “ZERO RISK. ZERO COST. MONTHLY REVENUE,” an archived version of the site shows.

That wasn’t the case for Circle K.

On the surface, things appeared fine: In March 2022, a Circle K vice president told a trade publication that the machines were a “big hit” and that customer feedback had been “overwhelmingly positive.” That August, Bitcoin Depot reported that it had placed more than 1,900 ATMs in the chain’s stores in the U.S. and Canada.

But behind the scenes, the volume of scams was becoming impossible to ignore and frustrated Circle K employees were flooding Bitcoin Depot with complaints, recalled two people familiar with the situation.

CNN and ICIJ spoke to a total of 30 Circle K current store clerks and managers who were aware of crypto ATM scams. Of those, 17 said they witnessed scams happen in their stores; 13 employees mentioned communication from corporate about crypto ATM scams either in the form of emails or employee training, according to a CNN analysis.

One store manager, who asked for anonymity to discuss their employer, said that nearly all of the clients who used the ATM were being defrauded. This manager said “98% are on the phone being scammed one way or the other.”

Scammers even snared Circle K workers, according to interviews with current store employees and police records. Pretending to be Circle K management, scammers persuaded clerks in multiple locations to put money in the Bitcoin Depot machines. The convenience store chain was forced to caution its staff to not fall for the schemes. At a store in Indiana, a sign behind the register warned clerks, “Don’t save money in the register to drop in the Bitcoin machine.”

Inside Bitcoin Depot, employees had long debated how to address the broader problem of scams, according to people familiar with the issue. In early 2023, the company changed the refund policy on its website, writing that scam victims would be eligible to have fees returned to them on a “case-by-case basis.” By late October that year, the language had been removed.

In response to questions about the situation, Bitcoin Depot said that “bad actors attempt to misuse many types of financial self-service terminals,” and “the issue is not unique to any one retailer.” The company said it has “refunded millions of dollars in attempted scam transactions” and that the language was removed because it “prompted individuals who were not victims to seek refunds for legitimate, completed transactions.”

Emails sent in response to consumer complaints showed that even when refunds were available, onerous requirements made it difficult to get them. One Florida victim said she was denied a refund when she wasn’t able to get a police report by Bitcoin Depot’s deadline. And refund instructions on the company’s website led to a form that didn’t exist, one person wrote in a complaint to the Connecticut Department of Banking. Bitcoin Depot ignored a victim’s refund request while two of its competitors promptly returned lost funds, according to state records.

In its responses to consumer complaints and lawsuits, Bitcoin Depot repeatedly blamed victims for falling prey to scammers, arguing that they failed to heed the company’s warnings and policies, according to court records and documents ICIJ obtained through public records requests. Scam warnings are prominently placed on Bitcoin Depot’s ATMs, and users are shown additional messages during the deposit process, cautioning them against sending money to people they don’t know. Users must also verify that they are depositing funds into their own wallet and accept that all transactions are “final and irreversible,” the company says.

But the messages often aren’t sufficient to deter victims, who are typically distraught and not thinking clearly, according to law enforcement officers, consumer advocates and industry insiders interviewed by ICIJ. That was the case for Beckett, who said that he didn’t notice the warnings until after he had lost his money.

It was the same for Danny Foret, who was lured into putting nearly $20,000 into a Bitcoin Depot machine at a Circle K in Louisiana. “I was so upset, I didn’t worry about looking at the machine,” he said.

“That’s where the vulnerability of the victims shows,” said Brad Williams, a police detective in Peachtree City, Ga., who has investigated bitcoin ATM scams and is working to regulate the machines. “These scams can go on for days and days and days,” he said, and when a victim has been broken down psychologically, “it doesn’t matter what’s in front of them.”

Bitcoin Depot told ICIJ that it believes scam warnings are “beneficial” and that it reviews each scam report. “In many instances, we are able to block a transaction before funds reach a bad actor or provide some relief,” the company said, adding that while it believes customers need to protect themselves from scams, it “recognizes that customers should not bear this burden alone.”

Refund requirements, it wrote, are “not intended to burden customers, but to ensure requests are handled responsibly and in compliance with applicable legal and regulatory obligations.”

‘Not our problem’

Some retailers have become disillusioned with the machines and tried to have them removed or turned off.

In April 2024, Fareway Stores, a chain of grocery stores, signed a deal with Bitcoin Depot to install 66 machines in its stores in Iowa and other states. By the following February, it had unplugged them all.

The machines, Fareway alleged, had become “instrumentalities of massive fraud.” By the beginning of 2025, customers were being defrauded almost weekly, and not long after Fareway found itself under investigation by both the Iowa Attorney General and the state lottery agency.

Bitcoin Depot sued for breach of contract, demanding Fareway turn the ATMs back on and pay damages for lost business and reputational harm.

As of September, 18 states have passed laws or regulations to protect consumers against crypto ATM scams, and more are considering legislation, according to AARP. The changes include maximum transaction limits and, in some cases, mandatory refunds for victims.

But even heavy restrictions have failed to stop scammers from using the ATMs. After Minnesota introduced a $2,000 daily transaction limit for new ATM users in August 2024 as part of a broader law regulating the machines, the state’s Department of Commerce continued receiving complaints about them. In one such instance, the victim wrote that the perpetrator had stolen nearly $15,000 by instructing them to make 15 transactions and use a different name for each one.

New legislation enacted in Iowa, where Fareway is headquartered, has limited transactions to $1,000 a day and no more than $10,000 a month for first-time crypto ATM users. It has also capped operator’s fees at $5 per transaction or 15% of the value of purchased cryptocurrency, whichever is greater.

With the law coming into effect in summer 2025 and legal pressure from Bitcoin Depot, Fareway decided to turn the ATMs at all of its stores back on in May, according to court filings. The law, it hoped, would at least limit future damages to its customers.

It’s usually an older or elderly person on the phone with someone and has a bank envelope with them, but the last person… was in her 30s or 40s and she got scammed. — Debbie Joy, assistant manager at a Circle K in Florida

Fareway and Bitcoin Depot settled the suit in November, shortly after Bitcoin Depot announced that it would begin requiring ID verification for every transaction and would add “additional protections for seniors.” The company did not provide details about the measures.

Debbie Joy, an assistant manager at a Circle K in Port Orange, Fla., told CNN that she estimates she has intervened in at least 10 scams involving the Bitcoin Depot ATM in the store during her four years of working there, and now she can spot the warning signs.

“It’s usually an older or elderly person on the phone with someone and has a bank envelope with them, but the last person was about my age,” Joy said. “She was in her 30s or 40s and she got scammed. I had just walked into work and it was too late. She was outside crying.”

The scams happen so often that Joy has saved the cellphone number of a local police investigator. Rather than dialing 911, she calls him directly.

“I don’t think as much has been lost in my store because I try to intervene,” she said.

The city council gave her an award in April for stepping in to stop an elderly couple from depositing $10,000 into the Bitcoin Depot machine. Joy thinks she has helped three or four other people who were going to be scammed on the machine.

“Circle K policy is it’s not our machine, it’s not our problem,” she told the council, “but I see it all too often.”

Contributors: Patricia DiCarlo, Tim Elfrink, Matt Lait (CNN); Agustin Armendariz, Denise Ajiri, Sam Ellefson, Miguel Fiandor Gutiérrez, Whitney Joiner, Delphine Reuter, Annys Shin, Richard H.P. Sia (ICIJ)