IMPACT

Brands drop Singapore-listed palm oil giant after Deforestation Inc. exposé

ICIJ partner The Gecko Project previously found evidence the company, First Resources, violated its sustainability pledges and secretly controlled companies that cleared swaths of Indonesian rainforest.

Eight companies say they have suspended sourcing from palm oil giant First Resources after ICIJ partner The Gecko Project found the billionaire family behind it secretly controlled a network of “shadow” companies that cleared more forest for palm oil than any other firm in Southeast Asia.

The brands include skincare company Beiersdorf, which produces Nivea moisturizers; cleaning and personal care company Procter & Gamble; food manufacturers FrieslandCampina, Danone and Vandemoortele; laundry and hair-care company Henkel; vegetable oils firm Lipsa and chemicals company BASF, The Gecko Project reported.

In November, the U.K.-based investigative outlet revealed evidence that a trio of ostensibly independent Indonesia-registered companies were controlled by the Fangiono family, the majority shareholders of Singapore-listed First Resources, in breach of the company’s “sustainability” pledges and claims.

Reporters interviewed 14 former staffers who were employed by at least one of the four companies, FAP Agri, New Borneo Agri, Ciliandry Anky Abadi, and First Resources. Most of them said they considered the companies to be part of the same corporate group. First Resources has denied controlling FAP Agri and told The Gecko Project that NBA and CAA were neither its “subsidiaries, associated companies, nor related parties.”

“It’s good to see that [consumer goods] companies have responded with suspensions,” Gemma Tillack, forest policy director at the nonprofit Rainforest Action Network told The Gecko Project. “It is critical that we see immediate action in cases where shadow companies are involved in deforestation, so the investigation is setting an important precedent for the palm oil sector.”

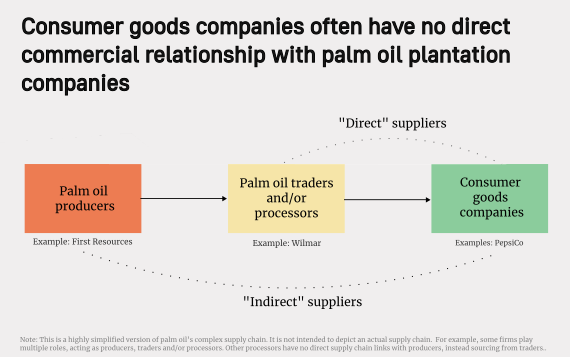

But not all of the 16 consumer goods firms and palm oil processors contacted by The Gecko Project are cutting ties with First Resources. Seven of the companies — including food and beverage company Pepsico, household and personal care company Colgate-Palmolive and Belgian chocolate-maker Barry Callebaut — claimed to be in the process of contacting the companies they buy palm oil from directly, citing complexities in their supply chains. Those companies, in turn, source palm oil from First Resources, according to The Gecko Project.

“While we request timely action, the timeline of the investigation is stipulated by our suppliers’ grievance processes,” Sara Thallner, Barry Callebaut’s head of corporate communications, told The Gecko Project.

The Gecko Project’s findings were part of ICIJ’s Deforestation Inc., a cross-border investigation that exposed how the lightly regulated sustainability industry allows human rights violations and deforestation to go unchecked.

The collaboration revealed how companies often rely on industry certifications based on flawed audits to claim compliance with labor laws and environmental and human rights standards. ICIJ found that in the past two decades, more than 340 forest-product companies touting products and operations certified as “sustainable” were later accused of environmental crimes or other wrongdoing by local communities, advocates and government agencies.

First Resources is not the only natural resources firm accused of using secretive companies to mask deforestation in its supply chain. This week, a new report from Greenpeace, Environmental Paper Network and other conservation organizations uncovered links between an Indonesian pulpwood concession operator allegedly responsible for mass deforestation and a conglomerate owned by Indonesian billionaire Sukanto Tanoto.

As part of its ongoing investigation of First Resources, The Gecko Project contacted six commodity traders that have direct commercial relationships with the company. Several said that they were waiting for the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, an industry group known as the RSPO, to rule on a formal allegation that First Resources controls FAP Agri and CAA.

But the RSPO has already spent three years investigating the complaint without conclusion, The Gecko Project reported. Meanwhile, environmental organizations have called for stronger regulations that would force companies to react more swiftly to reports of human rights and environmental abuses.

In the EU, a directive that would require companies to keep a closer eye on their supply chains, known as the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, has gained traction but suffered a setback on March 15, when the number of companies subject to it was slashed by almost two-thirds, according to The Gecko Project. If the European Parliament approves the directive in April, the bloc’s member states will have two years to implement the new law.

“It’s important that companies realize mandatory due diligence legislation is coming up everywhere in the world,” Amandine Van Den Berghe, a trade expert at environmental law nonprofit ClientEarth, told The Gecko Project.