FINCEN FILES

Controversial shell-company ‘factories’ seek a role cleaning up UK’s reputation

It would ‘put the fox in charge of the henhouse’, anti-money-laundering experts warn, after FinCEN Files identified thousands of U.K. shell companies linked to suspicious transactions.

A trade group representing firms that specialize in corporate secrecy has been lobbying the British government to give its members a central role in efforts to counter the country’s reputation as a leading provider of front companies to organized crime groups, corrupt regimes and other criminals.

The proposal is being pushed by the United Kingdom’s Association of Company Registration Agents, which is urging government ministers to hire ACRA members to carry out identity verification checks on the owners of all firms listed at Companies House, the U.K.’s much-abused register of companies.

The plan was immediately met with skepticism by anti-money-laundering experts who noted that several members of ACRA specialized in setting up the kinds of anonymous U.K. companies — including “limited liability partnerships” and “limited partnerships” — that had long been popular with money launderers and had damaged the U.K.’s reputation internationally.

“It’s a bit like asking the fox to look after the chickens,” said Graham Barrow, an expert who has advised several global banks on combating money laundering.

Helena Wood, of the Centre for Financial Crime & Security Studies at U.K.-based think tank the Royal United Services Institute, has long argued that responsibility for all verification checks should be removed from company formation agencies and carried out independently. “We know loads of these [agencies] don’t check ID. Of course they’re not doing it. They’re absolute cowboys, some of them,” she said.

ACRA, which claims its members process close to a quarter of incorporations in the U.K. each year, is among a handful of organizations that have been appointed to an expert panel, advising the U.K. government on how best to implement Companies House reforms promised by ministers. Others on the panel include the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, the Institute of Directors, the Law Society, the National Economic Crime Centre and Transparency International.

We know loads of these [agencies] don’t check ID. Of course they’re not doing it. They’re absolute cowboys, some of them — Helena Wood

Last month, U.K. ministers hurriedly outlined Companies House reforms, two days before the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 109 media partners published the results of a 16-month international investigation known as the FinCEN Files.

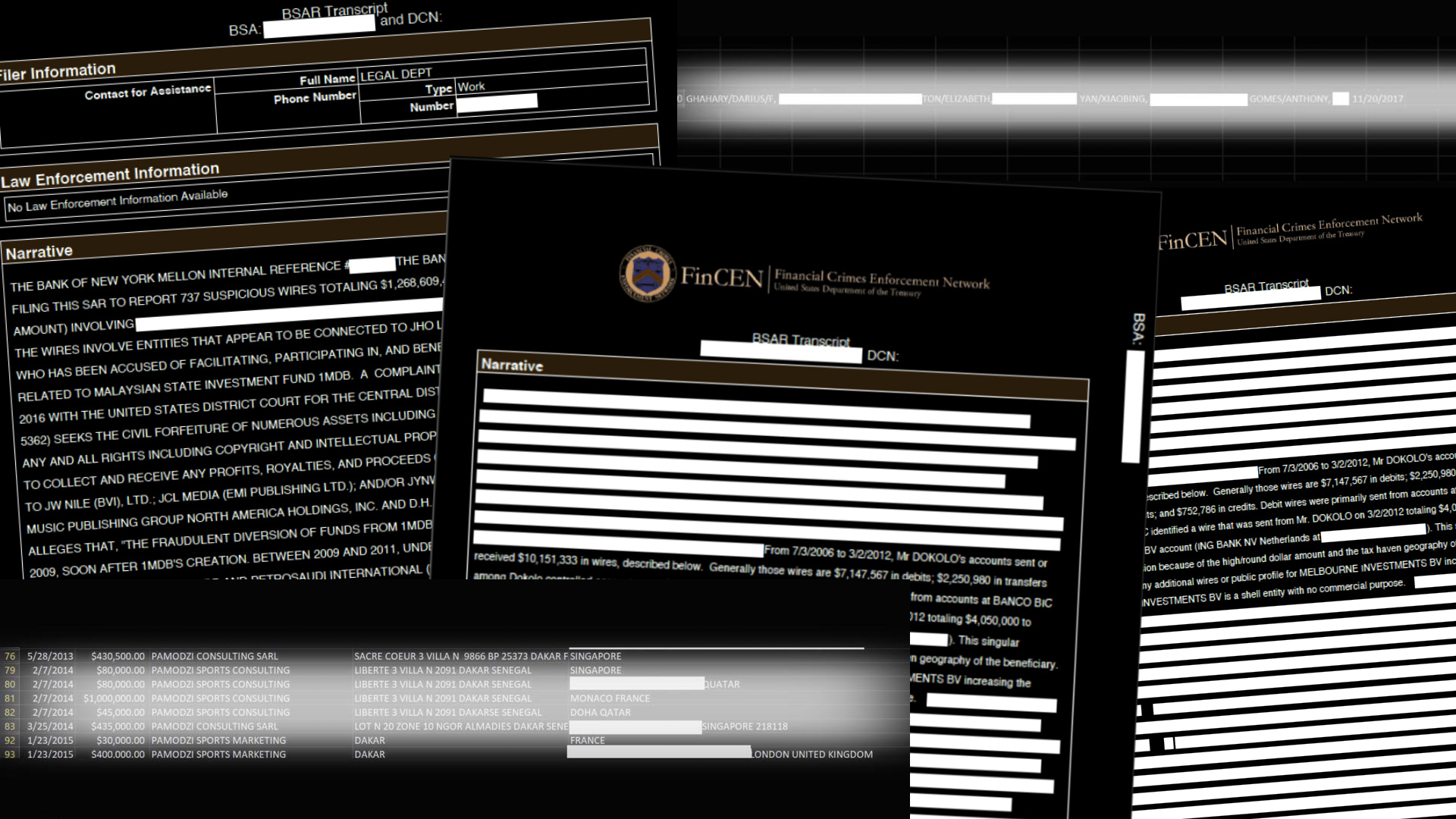

The investigation was based on a cache of secret documents, largely made up of more than 2,100 suspicious activity reports, secretly sent by banks to a unit of the United States Treasury Department called the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN. Obtained by BuzzFeed News, and shared with ICIJ and media partners, the FinCEN Files detail suspect money flows of more than $2 trillion between 1999 and 2017.

The secret documents are peppered with the names of 3,267 U.K. shell companies, most of which were created and maintained by a small number of company formation agencies, including at least one ACRA member. In one secret intelligence assessment, FinCEN analysts described the U.K. as a “higher risk” country for money laundering, on a par with Cyprus.

As part of its FinCEN Files research into U.K. company formation agencies, ICIJ found one individual who admitted signing off hundreds of financial statements, sent to Companies House, without knowing whether or not they were correct. Another said he had acted as a shadow director, setting up scores of firms from his flat in north London on instructions from a lawyer based overseas. Another denied knowledge of dozens of anonymous companies registered to her home address.

FinCEN Files reporters tracked down a dentist in Brussels, whose signature appeared on thousands of UK shell company financial statements. Leaked documents show that for nine shell companies alone, these financial statements had failed to record $4.1 billion of suspicious income flowing into the firms’ bank accounts. The dentist claimed his signature had been forged.

Not all of the formation agencies in ICIJ’s analysis were ACRA members, but some were. Comform Solutions, an agency set up by three old rugby teammates from a prestigious English boarding school, created and maintained 380 U.K. shell companies featured in the FinCEN Files, linked to suspicious transactions.

Another ACRA member, Armadillo Corporate Solutions, is owned by Manny Cohen, the flamboyant former owner of the U.K. franchise for Mossack Fonseca, the Panamanian law firm at the center of the Panama Papers scandal.

Also among ACRA’s membership is Markom Management, owned and run by Mark Omelnitski. Markom has repeatedly been linked to sanctioned members of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s inner circle Arkady and Boris Rotenberg, most recently in a U.S. Senate report about the use of expensive art to evade sanctions.

At the center of the plan to reform Companies House is an effort to verify information submitted to the register, in particular the details of who ultimately owns each U.K.-registered company.

Gareth Jones, chair of ACRA, told ICIJ, “We continue to say to government, ‘Well, this is going to cost a lot of money, so implementing all these checks in Companies House is not going to be pain free.’ …We continue to say wouldn’t it be better to rely on a third party to undergo those checks… [Companies House] should rely on our members to do their identification and due diligence checks for them.”

Jones, who served as chief executive of Companies House between 2007 and 2015, insisted ACRA members abided by a code of conduct and were not engaged in the worst practices seen in the industry.

“Our members, and we as an organization, are keen to be part of, and to be associated with, anything that’s prepared to bear down on any use of U.K. corporate vehicles for the wrong purposes,” he said.

He pointed out that several non-ACRA formation agencies that created U.K. companies were based overseas, beyond the reach of U.K. anti-money-laundering regulation.

“My members are all regulated,” he said. “Overseas agents, by and large, don’t have to demonstrate their regulation credentials in the way that we do. That’s another of the issues we have concerns about and we’ve passed those concerns on to [the U.K. government].”