The Metropolitan Museum of Art has agreed to repatriate two ancient sculptures from its collection to Nepal, in the museum’s latest effort to stem a tide of scrutiny over the dubious origins of some of its prized cultural relics.

The Met is making arrangements to return the two pieces — a 13th-century wooden temple strut and an 11th-century stone image, Vishnu Flanked by Lakshmi and Garuda — to the Nepali government after “receiving new information from colleagues in Nepal,” the institution said in a statement on its website.

The museum purchased the temple strut in 1988 and received the stone sculpture as a gift from a wealthy American collector in 1995. In 2021, an anonymous Facebook account, Lost Arts of Nepal, identified the statue of the Hindu god Vishnu as one stolen from a shrine in the Nepali village Bungamati in the early 1980s.

“We value the long-standing relationship we have fostered with scholarly institutions and colleagues in Nepal, and we are committed to continuing the ongoing and open dialogue between us,” Max Hollein, the museum’s CEO and director, said the statement.

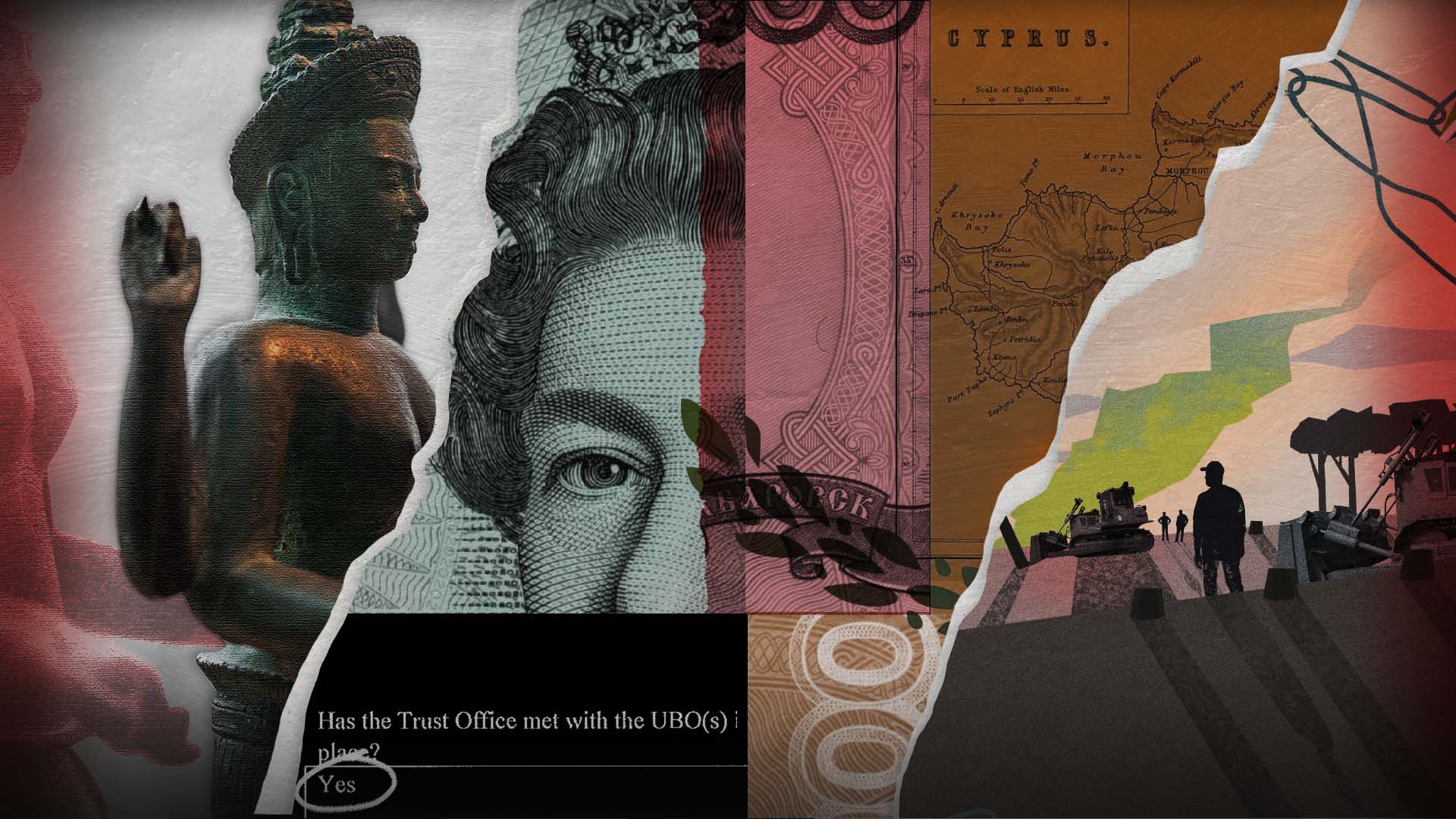

The statue of Vishnu was among several Nepali relics featured in an ICIJ investigation in March, which found at least 1,109 pieces in the Met’s collection were previously owned by people who had either been indicted or convicted of antiquities crime. Of the artifacts identified by ICIJ, 309 were on display at the time of the investigation.

Fewer than half had records describing how they left their country of origin — even those from places with strict and longstanding export laws. For example, the museum’s catalog included more than 250 antiquities from the heavily-looted regions of Nepal and Kashmir but only three were listed with any origin records explaining how the objects left the regions.

“Nepal has a living religion where these idols are actively worshipped in temples. People pray to them and take them out during festivals for ceremonies,” Roshan Mishra, a volunteer with the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign, told ICIJ in March.

“When relics are stolen, those festivals stop. Each stolen statue erodes our culture. Our traditions fade and are eventually forgotten.”

Less than two months after ICIJ’s investigation, the Met announced the creation of a new four-person team to bolster its existing provenance research efforts and scour the museum’s 1.5 million-piece collection to root out artifacts of questionable origin.

In a separate statement, Hollein said recruitment for the positions — including a leadership role — was “well underway,” with announcements expected in the coming months.

“Mindful that there are no quick or easy solutions, I am happy to report that we are making sustained and significant progress,” Hollein said in the statement.

The Met is among several world-renowned art institutions reckoning with catalogs littered with relics that may have been stolen and smuggled overseas. In recent months, there’s been a spate of high-profile art repatriations to Cambodia, India and elsewhere as governments seek to retrieve long-sought lost treasures.

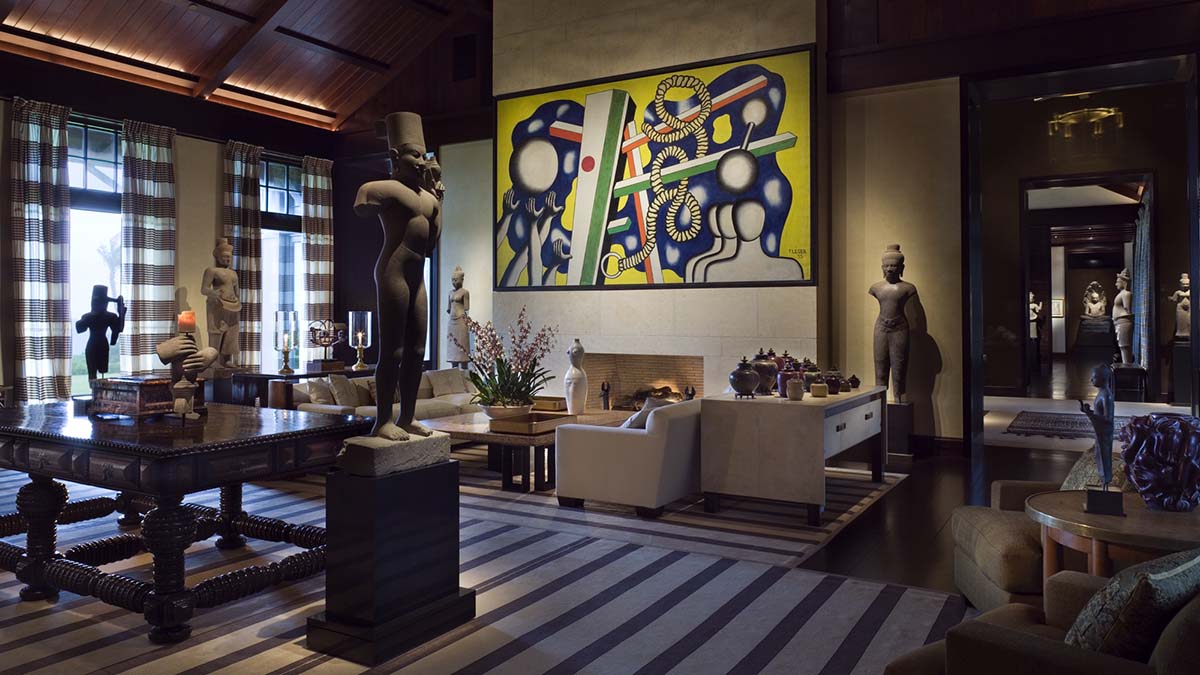

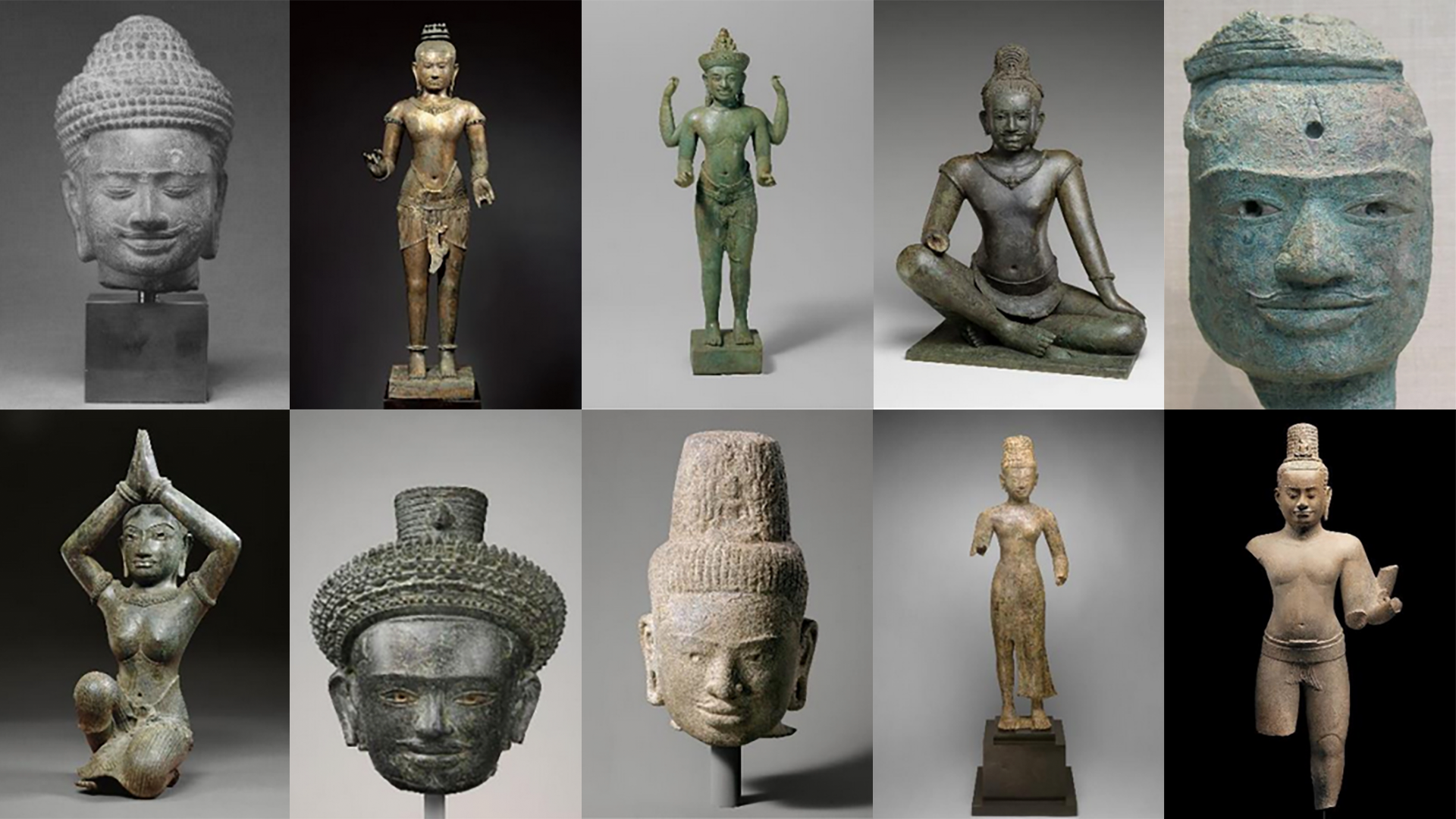

Private collections are also under increased scrutiny. Last month, the family of billionaire George Lindemann agreed to turn over 33 ancient statues to Cambodia, including some officials said were stolen and trafficked to the United States.

A previous ICIJ investigation linked some of the 10th to 12th-century statues to late disgraced art collector Douglas Latchford, who was accused of overseeing a booming trade in looted ancient art from conflict-riven Cambodia and its neighboring countries for decades. In June, his estate agreed to pay $12 million and return a 7th-century bronze statue as part of the largest-ever forfeiture of money linked to allegedly stolen antiquities.

Art historian Angela Chiu told the Washington Post at the time that the forfeiture was a “signal” from U.S. authorities.

“They’re not just going to seize the artworks,” she said. “They’re going after the ill-gotten gains these smugglers have made.”