At ten minutes past midnight on Aug. 5, 2000, police from the Milanese suburb of Cinisello Balsamo received a tip from a confidential source about a man known as “Leo” or “Leon.” He was said to be hanging out at a smart party in room 341 of the Hotel Europa, where substantial quantities of cocaine were being consumed.

The tip turned out to be excellent. As they entered the room at the hotel, the officers found four scantily clad women gathered around a man. They searched the room and found 58 grams of the highest quality coke. One of the girls, a Russian, was diluting it.

The policemen had no idea who it was they hauled back with them to the station. The name Leonid Minin, a 52-year-old Israeli industrialist originally from Odessa in the Ukraine, meant nothing to them. Minin is, in fact, an Israeli citizen with an Israeli passport, but also has passports from the former Soviet Union, Russia, Germany and Bolivia.

The initial investigation in Monza, the Milanese suburb where Minin was held, revealed little of interest. Some prostitutes had been pampering a businessman, who was fond of cocaine and sex. Under questioning, he admitted to sniffing 30 to 40 grams a day. He spent about $1,500 a day on his habit. But he could afford it: he also had bank deposits worth up to $3 million. He told the investigators he had come from Sofia and traded precious wood from Liberia and owned companies in China, Liberia and Gibraltar.

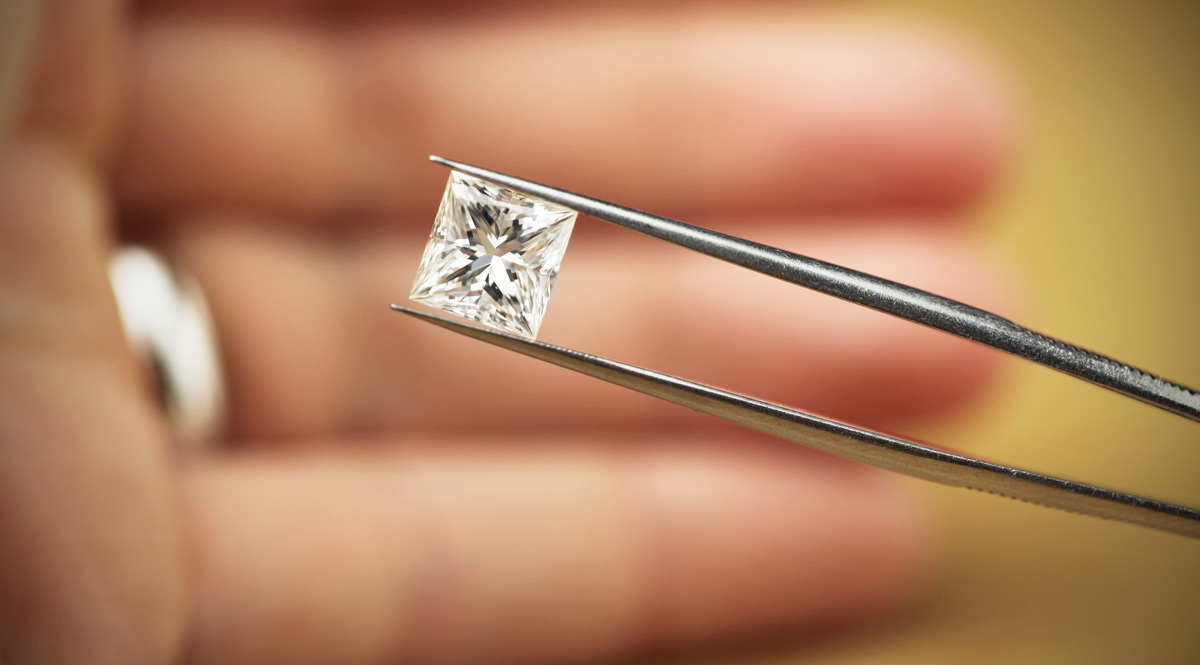

The police knew that Minin was hardly a pauper. When they arrested him, he had $25,000 and 12.5 million Italian lira (almost $6,000) in cash on him, as well as Mauritian rupees, Hungarian forints and some polished diamonds, worth nearly $500,000. “Some of those diamonds come from the selling of my shares in a company I own on the island of Mauritius,” Minin told them. But despite his wealth, he wasn’t able to get out on bail because of the seriousness of the drug possession charges.

The authorities in Monza were, at first, unaware whom they had arrested. It was not until weeks later that they learned that the man with the expensive drug habit and the fondness for beautiful women was under investigation in five countries for various crimes. It would take even longer to piece together the documents that he carried with him: the papers would tell the story of his illegal arms trading, including selling weapons to the most brutal of Africa’s rebel insurgencies, the Revolutionary United Front in Sierra Leone.

Before his arrest for drug possession, Minin operated with near impunity as an illegal arms dealer and an ally of brutal regimes. He was also a high-ranking member of a Russian organized crime syndicate. His arrest was fortuitous, but also a disturbing illustration of the inability of law enforcement agencies to prosecute criminals whose operations are international in scope.

A lack of international coordination among law enforcement and intelligence agencies has allowed arms dealers like Minin to develop complex businesses involving individuals, companies and governments in dozens of countries, a nearly two-year global investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has found.

While the Italian police who arrested Minin had no idea who he was for several weeks, intelligence services across Europe had no idea that the infamous mobster had been arrested on a mundane drug charge. Unlike the police in Monza, the spy agencies had lengthy dossiers on Minin.

Switzerland, for example, banned him from entering the country in February 2000 and recorded his aliases: Leon Minin, Wulf Breslav, Igor Osols and Leonid Bluvshtein. According to the Swiss authorities, he had been arrested in Germany in the mid 1970s for falsifying stolen identity documents, and had a record of fraudulent dealings in the art world.

The Swiss were sketchy about his more recent activities, but did know that “for several years he has been depositing millions of dollars in Europe and Switzerland – according to him, from international oil trades.” Other European intelligence agencies helped fill in the gaps – the money, they had discovered, was laundered from sales of oil stolen from Russia.

Belgium, too, had intriguing files on Minin: on Dec. 18, 1994, in a smart Brussels suburb, three men had assassinated a certain Vladimir Missiourine, who had connections to the “oil mafia” of Odessa – an international organized crime group. Investigators traced calls made by Missiourine to a company in Rome, Galaxy Energy, which was owned by Minin.

Another Belgian judge suspected Minin “of giving $200,000 to a [Philippe] Rozenberg, [a member of parliament] in order to obtain identity documents to allow him to set up a base in Belgium,” according to court documents in the case. Rozenberg is still under investigation, has not been charged, and has not commented publicly on the investigation.

France, which had issued a public intelligence report on Minin for possession, transport and use of cocaine, also had a large file on him. One intelligence report stated that Minin “left the USSR in 1967, where he was known for racketeering.” France claimed he had moved on to Bolivia, Switzerland, Germany, Monaco and Italy. Once again, he was dealing in oil products, and once again with oil mafia connections — “maintaining relations with confirmed members of the (criminal underworld) originating from CIS [the Commonwealth of Independent States, the successor entity to the Soviet Union], such as Viatcheslave Ivankov, considered by the American authorities as the Russian Mafia kingpin in the United States, and Andrei Skrylev, suspected of being an important drug trafficker in Eastern Europe.”

Like Switzerland, Monaco had declared him a prohibited immigrant on June 18, 1997. The French docket also referred to information from the Italians themselves: “At the end of 1998, the Italians authorities regarded Minine [sic] as the head of a criminal group of Ukrainian origin, close to the criminal organization Solnstevo [sic] and specializing, among other things, in the international trafficking of weapons and narcotics, money laundering and extortion. In Ukraine, Minine [sic] maintains close relations with Alexandre Angert, the head (pivot) of organized crime in Odessa.”

And while the public prosecutor’s office in Monza had never heard of the man, the Italian national police were very familiar with Leonid Minin. As far back as October 1998 the Italians had compiled a detailed report, which declared that Minin was “one of the most important members of the ‘Neftemafija’ ” – that is, the oil mafia, based in Odessa.

The report was based on the work of the Servizio Centrale Operativo, the elite investigative unit and the nerve center of the Italian National Police, which at the time had spent almost a year on a complex investigation of a Ukrainian criminal group associated with the Russian mafia and involved in international arms and drug trafficking, money laundering, extortion and other offenses. The leader of the group was listed as “Minin Leonid.” The report chronicled Minin’s taste for cocaine, but the 1998 investigation focused on Minin’s activities at the oil terminals in Odessa and on the laundering of his oil money.

The investigators were also interested in his role as head of an organization, the Neftjemafija, that included top members of the Ukrainian mafia, such as Alexandre Angert, alias “Angel,” and Nicholay Fomichev, alias “Kolija.” The report said these men had “a large quantity of weapons such as guns, machine-guns, pistols, hand grenades [sic] and explosives.”14 The report also described assassination attempts on some politicians at election time in Odessa.

In July 1997, Angert, Fomichev and two bodyguards had been intercepted on the main road encircling Brussels, the investigators noted. In a video camera the men had been carrying, the police found a cassette that appeared to have just been recorded in Eastern Europe – of a training camp for bodyguards and assassins. Minin appears on the tape, which also shows armed men in training, shooting targets and using pump action shotguns.

When the report was compiled – between 1997 and 1998 – its analysis of Minin’s phone and travel activity did not reveal any connections to Africa.16 But when he was arrested in Milan, investigators discovered clues about his new life: contracts, faxes and letters related to Liberia, weapons catalogs and price estimates, and end-user certificates issued by the Ivory Coast, price lists for weapons, ammunitions and military goods.

Yet before those clues could be studied, there was still the matter of Minin’s arrest in the Hotel Europa and subsequent trial. In 2000, Minin was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison for possession of drugs. Minin’s appeal failed. With the drug case finished, Walter Mapelli, the public prosecutor, turned his attention to investigating the documents found in Minin’s luggage that threw light on his arms sales, including sales to some of Africa’s most brutal thugs.

No living thing

Ostensibly created to challenge the corrupt regime of Joseph Momoh in Sierra Leone, the Revolutionary United Front never managed to construct a coherent ideology. At best, its leader, Foday Sankoh, a former army corporal who had been exiled to Libya after leading a failed coup, spouted a half-baked version of pan-Africanism inspired by Col. Moammar Gadhafi’s “Green Book,” the Libyan leader’s political manifesto. Published in 1976, the book is replete with the Libyan leader’s own brand of revolutionary ideas on economics, political theory and social musings.

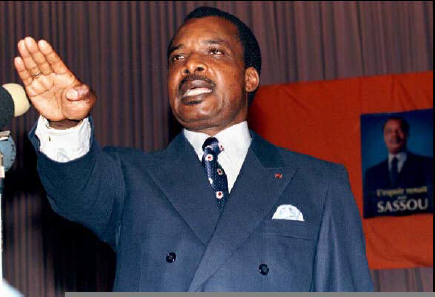

The origins of the war in Sierra Leone had more to do with the frustrated ambitions of Charles Taylor, a warlord in neighboring Liberia, than any ideology of the RUF to better the country. In 1990, a peacekeeping force assembled by the Economic Community of West African States – including two units of troops from Sierra Leone – thwarted Taylor’s attempt to seize the Liberian capital, Monrovia. An angry Taylor warned in a radio broadcast that neighboring Sierra Leone would “taste the bitterness of war.”

At the time Taylor, though not a head of state, was in control of a large part of the Liberian interior, a territory known as Greater Liberia. He ran his fiefdom as a business, exporting timber, iron ore and other commodities through the port of Buchanan. As he took control of trade in the interior, he soon became interested in the rich deposits of diamonds on the Sierra Leone side of the border. The RUF became the instrument of Taylor’s vengeance and greed.

In March 1991, the RUF struck across the border with several units of Taylor’s armed forces, as well as mercenaries from Burkina Faso. The first target they hit was the diamond-rich district of Koindu. Throughout the 1990s, as the United Nations and other international agencies have documented, Taylor and his foreign partners used the RUF to profit from Sierra Leone’s diamonds, while the RUF launched a campaign of unprecedented brutality against the population of Sierra Leone.

Among the worst episodes was the January 1999 campaign aptly called “Operation No Living Thing.” Over four months of slaughter, RUF thugs killed 5,000 people, and amputated the arms, hands, feet and ears of thousands more. Some 150,000 people were left homeless by the RUF’s rampage; they burned down more than 80 percent of Freetown’s buildings – including mosques, churches and schools.

There were both motive and method to the madness of the RUF. A confidential intelligence report from the former British Foreign Secretary Robin Cook in 2000 concluded that Taylor’s strategy was to maintain his influence over the diamonds of eastern Sierra Leone through the RUF, capitalizing on the breakdown of all state authority in the area. Minin’s bag of documents provided a rare window into the details of the arms deals that fueled the conflict.

A frequent flyer, with cargoes of arms

A closed hearing on Nov. 28, 2000, opened the way for Mapelli to indict Minin. On June 20, 2001, he was charged with weapons trafficking, and for delivering a hundred tons of weapons, spare parts, ammunition and explosives to the Revolutionary United Front. Minin was charged with using false end-user certificates, and for delivering 68 tons of weaponry from Eastern Europe supposedly destined for Burkina Faso, and 113 tons marked for the Ivory Coast, to Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Documents from Minin’s luggage illustrated his methods. One fax sent to Minin on March 23, 1999, discusses missiles with a range of more than 4,000 meters. “The procurement can be done with ‘end-user’ or without. If we can declare that we can deliver without the Certificate, the Buyer can realize the procurement without going through a bidding procedure.” The advantage of this would be to keep costs down.

Another fax, sent to Minin on April 28, 2000, expressed an interest in communication satellites and launchers: “Rostelesat is planning to launch its 24 (plus 4 back up satellites) into orbit with SS-18 rockets. These rockets are converted from intercontinental ballistic missiles and our company obtained access to them for launching its satellites.”

Some of the letters and faxes appeared to be in code, discussing matters like the trade of flowers between Amsterdam and Israel — a reference, the prosecutor in Monza believed, to illicit diamonds. The United Nations, which was also investigating Minin’s involvement in arms trading, provided background that helped Italian authorities make sense of Minin’s role in two operations alluded to in the documents. In December 2000, a panel of U.N. experts determined that there was “conclusive evidence of supply lines to Liberia through Burkina Faso. Weapons supplied to Burkina Faso by governments or private arms merchants have been systematically diverted for use in the conflict in Sierra Leone. For example, a shipment of 68 tons of weapons arrived in Ouagadougou [in Burkina Faso] on 13 March 1999. They were temporarily off-loaded in Ouagadougou and some were trucked to Bobo-Dioulasso [in Burkina Faso]. The bulk of them were then trans-shipped within a matter of days to Liberia. Most were flown aboard a BAC-111 owned by an Israeli businessman of Ukrainian origin, Leonid Minin.” Those shipments violated international sanctions. In 1997, the United Nations slapped an arms embargo on the RUF. (It was less than effective. Arms continued to reach the movement through Liberia, which led the United Nations to put that country under an embargo in March 2001, with the intention of preventing the arms trafficking to the RUF.) On Jan. 10, 2001, Johan Peleman, one of the U.N. experts and a co-author of the December 2000 report, went to Mapelli’s Monza office to make a statement. Peleman told Mapelli about the delivery to Ouagadougou. According to Ukrainian documents, the weapons had been sold under the terms of a contract between the Ukrainian state-owned arms exporting company Ukrspetseksport and a Gibraltar company representing Burkina Faso’s defense ministry. An airplane belonging to the British company Air Foyle then delivered the weapons to Ouagadougou, on behalf of Antonov Design Bureau, a Ukrainian cargo shipper.

The arms did not remain in Ouagadougou. At first, Burkina Faso denied to the United Nations that the weapons were meant for Liberia, but later admitted the truth to the U.N. investigators: the arms had been shipped to Liberia in March 1999 using a BAC-111 belonging to Minin. Peleman’s account was supported by Mapelli’s investigation. When the Italians arrested Minin on drug charges in August 2000, he had been trying to sell the very BAC-111 used to transport the arms. His luggage was full of papers documenting the aircraft’s history, which any prospective buyer would want before purchasing the aircraft. A summary of the plane’s flights found in Minin’s luggage matched the U.N. account of the route that weapons shipped from Ouagadougou to Monrovia in March 1999 had taken. On March 6, Minin had left Odessa for Kiev and, on March 8, he went to Monrovia via Ibiza, in the Mediterranean. The records suggested that Minin, himself, could have closely supervised the shipment of weapons from Ukraine to Burkina Faso. And, according to the papers, the plane made several roundtrips between Monrovia and Ouagadougou during March to carry “Liberian Gov Cargo.” The Monza police also got two pictures taken during March 1999 that showed Minin’s plane at Bobo-Dioulasso airport. Another photograph showed the inside of a plane filled with boxes of weapons The U.N. experts also concluded that in the weeks before his arrest, Minin was planning to deliver a massive amount of weapons to Liberia via the Ivory Coast.

Among the documents taken from him were several copies of a buyer’s certificate signed by Gen. Robert Guei, then the leader of the Ivory Coast. According to this document, which was authenticated by the Ivory Coast embassy in Moscow, on May 26, 1999, Guei authorized the following to be bought in his name: 5 million rounds of 76 2x39mm Ball ammunition; 50 M93 30mm grenade launchers; 10,000 30mm bombs for M93 launcher; 20 thermal image binoculars. The authorization for the deal was made out to a certain Valery Cherny, from the company “Aviatrend.”

When the prosecutor confronted him with this document during a judiciary interview, Minin sought to distance himself from Cherny. He said he had met him by chance, and the Ivory Coast document had come into his possession by accident.

Minin explained that he had come across Cherny in a hotel in Italy, and that Cherny had left some of his documents in a green wallet in Minin’s room. “Poco verosimile” (hardly credible), was the Italian judge’s opinion of Minin’s explanation.

The judge’s opinion was soon confirmed. Minin shipped wood through his Liberian company Exotic Tropical Timber Enterprise (ETTE) – logging is one of the prime sources of revenue in Liberia and was a mainstay of Taylor’s forces – using Cherny’s trucks. Minin was forced to concede that he knew Cherny as his supplier of trucks, but still denied any involvement in an arms deal with Cherny.

When asked to explain other documents in his luggage referring to weapons, Minin said: “These are photocopies of magazines. I do not and have never been concerned with weapon trading. My company Exotic Tropical Timber Enterprise deals with wood. Aviatrend is not a company you can link to me. It belongs to Valery Cherny and this company (Aviatrend) has a contract with a Ukrainian company that produces trucks. They have sold lorries to Exotic Tropical for my company to transport timber from the interior of the country to Liberia’s ports.”

Other documents found in Minin’s luggage were to shatter this defense, too. One fax, sent by Cherny on an Aviatrend Limited letterhead, offered to furnish weaponry that was identical to that listed on the buyer certificate from the Ivory Coast. The fax was sent to a certain “Leonid.” Aviatrend bought the weapons in Ukraine and then offered them to Minin, even though the buyer certificate was under the name of Cherny. Other documents confirmed the deception. Another fax specified: “Delivery terms: FCA airport Bourgas. Delivery time: up to 30 days from date payment is received and after EUC [end user certificate] submitted.” The weapons were to be shipped through Bulgaria, and the price, according to various notes on the faxes, varied between $910,500 and $1,071,350.

The Italian prosecutor also managed to get hold of a bank order from Minin. On June 7, Minin had told his contact at Banco di Lugano, a Mr. Pessina, to pay $850,000 to Alpha Bank Ltd, in Nicosia, Cyprus, in the name of Aviatrend Limited. The transfer was purportedly for the “purchase of engineering for a wood industry.”

The delivery of the weapons eventually took place in the middle of July 2000, according to faxes sent by Aviatrend to the Ivory Coast defense ministry. Copies of the faxes went to Minin, who, at that time, was staying in room 204 of “Hotel Atlantic” in Sofia. Via fax, Minin received a blow-by-blow account of the weapons transaction. One telex dated July 11, 2000, sent to room 204, said an Antonov 124-100, registered as UR82008 and belonging to the Ukrainian company Antonov Design Bureau, would deliver on the following day 113 tons of cargo “cartridges UNOO14, 1.4S” from the Kiev-based military company Spetstehnoexport. According to the document, the captain of the plane, Vitalii Horovienko, would be assisted by 18 other Ukrainian citizens, and had to deliver the goods officially to the defense ministry of the Ivory Coast. The Italians then managed to prove that the buyer certificate dated May 26 – which was used for that July weapons delivery – was falsified. Marius Assemian, a counselor at the Ivory Coast embassy in Italy, testified to that on June 7, 2001.

There was plenty of circumstantial evidence to back up the hunch that the weapons were destined for Sierra Leone. Through his timber business, Minin had met with Taylor. The arms dealer was even closer to Taylor’s son, known as “Chucky” and “Junior,” who has been known to be active in Sierra Leone.

On July 27, 1999, a business contact of Minin’s (the same one who had written to him about “flowers”) sent a fax: “I flew from Spain straight to Turkey to start work on (.) special package for JUNIOR. We can deliver provided he can pay for it (.) Kindly arrange that I have a line of communication with JUNIOR in case I will need it. The package consists of 20-30 items, in addition to the 100 units you know about.”

Mapelli believed the figure of 100 referred to 100 missiles.

Another fax sent to Minin, dated Feb. 5, 2000, and signed by one of Minin’s associates in Liberia, shed further light on the relations between the arms dealer and the younger Taylor. The fax said: “Dear Leo, I’m just coming from Chucky’s house. He called me this morning for a business proposal …. Nature of the business: to be the sole importer of crude oil by-products to Liberia. Duration of the business: 2 to 3 years (.) so estimated profit would be around: 3,000,000 US$/month.”

Minin even paid expenses for Taylor’s son. The Italian investigation came across a fax, sent by the younger Taylor to “Minin-Switzerland” on Feb. 15, 2000, concerning the expenses he had incurred on a trip to Trinidad. Inscribed on the top of the fax was the single word “Pessina,” an apparent reference to Minin’s contact at the Banco di Lugano, which Minin used to pay for arms purchased from Aviatrend.

It is unclear on what else the two men were collaborating, since the younger Taylor cut off all ties with Minin after his arrest. Among the last documents seized and analyzed by the Italians was a hand-written fax by “Charles McArthur Taylor Junior.” The Liberian president’s son wrote to Minin: “And from this day forward never in your life ever contact me again.”

From bullets to ballots

British forces, acting as part of a U.N. peacekeeping force, entered Sierra Leone in 2000 after other U.N. troops had been forced to surrender to the RUF.

Step by step, they began to recapture the country’s districts and demobilize the rebel forces – about 47,000 fighters were disarmed.

By May 2002, the situation had finally turned around. Foday Sankoh was in jail in Freetown awaiting trial for murder; Leonid Minin was in jail in Italy, awaiting trial for gunrunning, scheduled for December 2002; Charles Taylor was warding off an offensive by rebels from the Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy and had seen the war move to within 25 kilometers of his own capital, Monrovia.

On May 14, citizens of Sierra Leone went to the polls and peacefully re-elected Ahmad Tejan Kabbah as president. Ed Royce, the Africa subcommittee chairman in the U.S. House of Representatives, commented: “One can’t help but be moved by the photos of Sierra Leoneans who had their hands amputated managing to cast ballots.”