Nearly three years after their publication, the Panama Papers may have snared another former head of state.

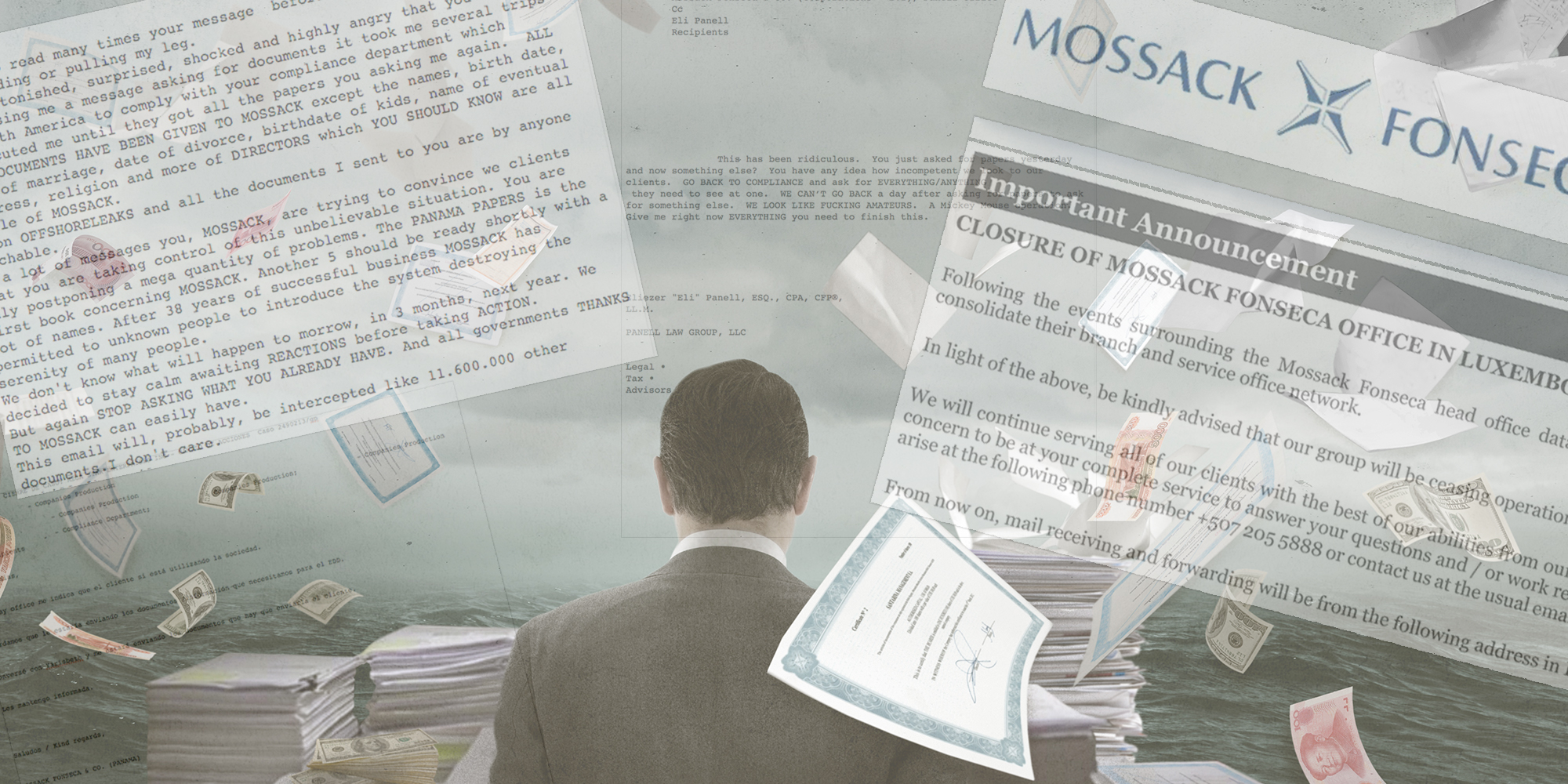

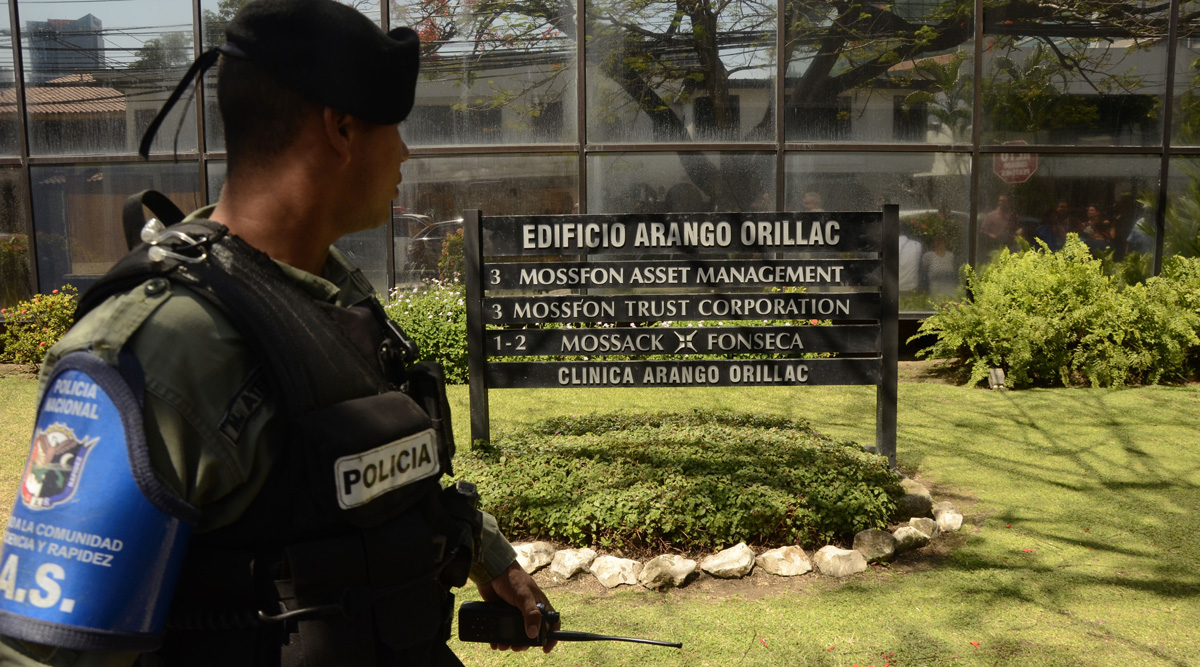

El Salvador’s Mauricio Funes was accused on Jan. 4 by the country’s attorney general of taking bribes while in office that were routed through offshore companies created by the now-shuttered Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. The former president and several associates were charged with money laundering for allegedly disguising $3.5 million that they received in bribes from a state contractor.

The offshore companies used in the alleged scheme were initially uncovered by El Faro, a leading digital news outlet in El Salvador that partnered with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists on the Panama Papers investigation in April 2016.

Jimmy Alvarado, a reporter with El Faro who reported on the Panama Papers, said that Funes was the third one-time Salvadorean president to be charged with money laundering or diversion of state funds.

“I think this shows that corruption in El Salvador is a structural issue,” Alvarado said. “It is happening on all sides.”

Funes and a close associate, coffee tycoon Miguel Menéndez Avelar, were charged with taking $3.5 million in bribes from an Italian construction company in exchange for steering inflated payments from a state contract to the company, according to statements by El Salvador’s attorney general Douglas Meléndez.

Meléndez said the men were accused of routing the funds through two companies, Headford Business S.A. and Rayne Services Corp., which were set up in Panama with the aid of Mossack Fonseca.

The money was later allegedly used for the purchase of land by Funes’ partner, Ada Mitchell Guzmán Sigüenza, and for the construction of a luxury spa, among other spending. Guzmán is the mother of Funes’ youngest son.

Funes, a former television anchor, led El Salvador from 2009 to 2014. He belonged to the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front party, which was formed by a leftist guerilla movement established during El Salvador’s civil war in the 1980s, but he governed largely as a moderate.

Funes and Guzmán are currently living in Nicaragua, where Funes has been granted political asylum by Nicaragua’s autocratic president Daniel Ortega.

Meléndez announced the allegations against Funes the day before his term as attorney general expired on Jan. 5. El Salvador’s Congress recently rejected a second term as attorney general for Meléndez, who had forcefully tackled corruption and brought cases against two other former presidents, Antonio Saca and Francisco Flores.

Last September, Saca was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment after he pleaded guilty to money laundering and embezzlement involving more than $300 million in public funds.

The incoming attorney general, Raúl Melara, the former director of the trade group the National Association of Private Enterprise, has not yet stated how he will handle the Funes case, said Alvarado of El Faro.

Alvarado said the charges demonstrate the critical role of offshore finance in acts of corruption by members of government.

“I hope that this brings into the debate the issue of offshore accounts and the need for transparency,” Alvarado said. “And the use of offshore companies by public officials.”