How US lawyers and bankers aided powerful Haitian tycoons now sanctioned over corruption by Canada

Two wealthy Haitians recently sanctioned by Canada owned or had other links to almost 20 companies and trusts created in some of the world’s most secretive tax havens, according to documents from the Pandora Papers.

Two Haitian millionaires accused by Canada of corruption and enabling murderous gangs to run rampant across the long-suffering island nation were helped for years by U.S. lawyers and bankers to buy offshore companies and such luxuries as a multimillion-dollar ocean-view home in Florida, records show.

In December, the foreign ministry of Canada sanctioned Gilbert Bigio, who is often referred to as Haiti’s richest person, and insurance magnate Sherif Abdallah, calling them “members of the Haitian elite who provide illicit financial and operational support to armed gangs.”

Together, Abdallah and Bigio owned or had other links to almost 20 companies and trusts created in some of the world’s most secretive tax havens, according to documents from the Pandora Papers, a global investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Lawyers and bankers in Miami provided the men with tax advice, letters of reference and other services, according to leaked files that formed the basis of the 2021 investigation by ICIJ and media partners.

“Canada has reason to believe these individuals are using their status as high-profile members of the economic elite in Haiti to protect and enable the illegal activities of armed criminal gangs, including through money laundering and other acts of corruption,” the government said in announcing the sanctions.

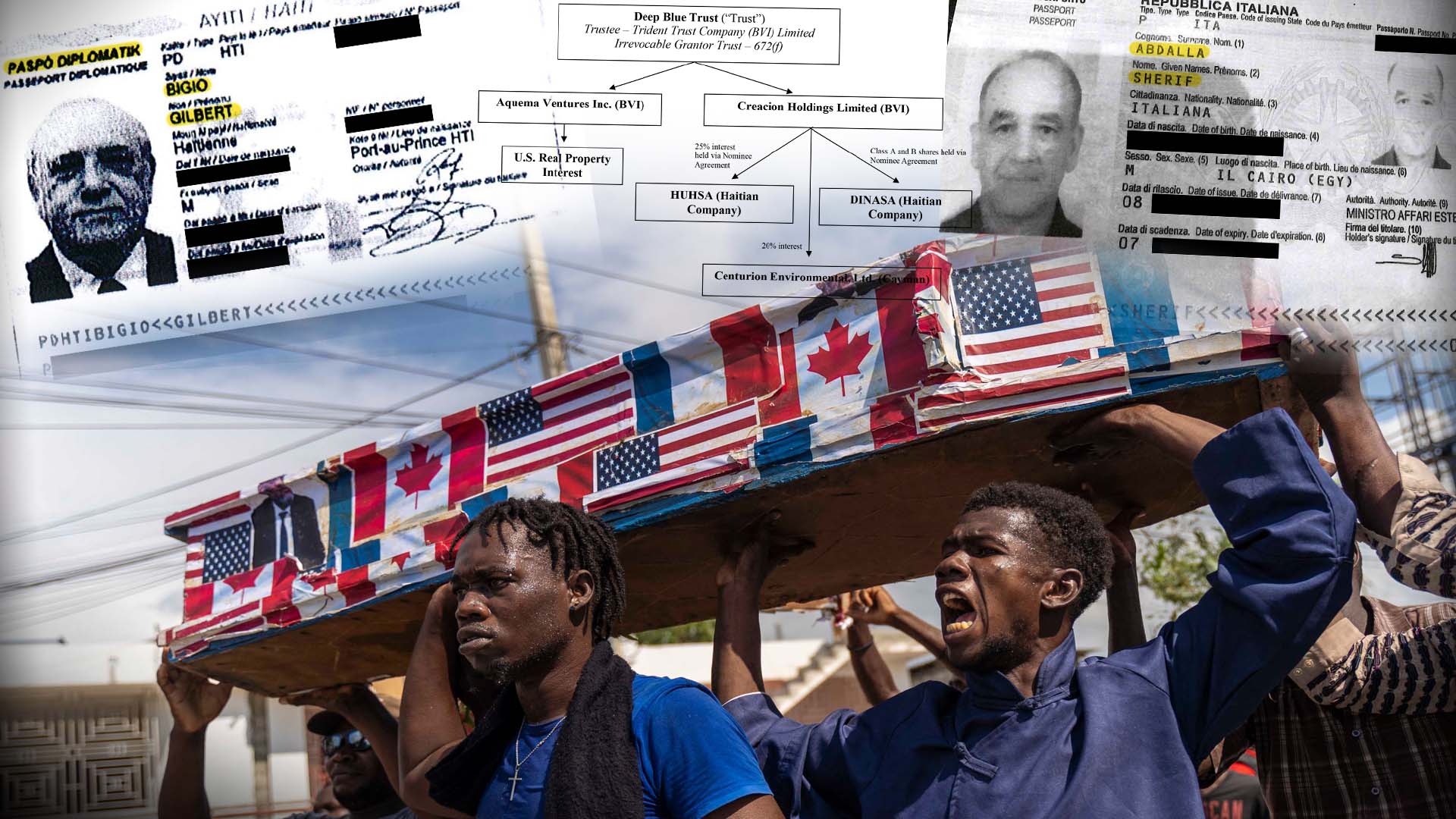

The blacklisting came in response to what experts are calling Haiti’s worst humanitarian crisis in decades. So far, the foreign ministry in Ottawa has sanctioned 15 Haitian politicians and business moguls, including Bigio and Abdallah.

“Those who invest in this economy at one level or another know they must be ready to have their own armed groups to protect themselves,” Jacques Jean-Vernet, a professor at Haiti State University in Port-au-Prince, told ICIJ. “We all know their practices, but no one dares do anything.”

Bigio and Abdallah did not respond to requests for comment.

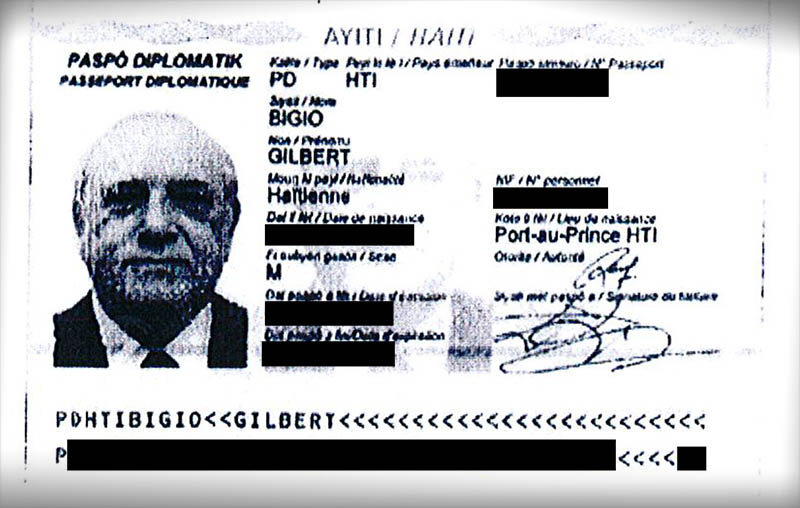

Bigio, 87, made his fortune through decades of major deals. He built a steel mill, opened a bottling company and acquired oil industry assets across the Caribbean.

In the early 1990s, the U.S. government sanctioned Bigio, his wife, son and others for their support of a military coup that ousted Haiti’s first democratically elected president. Years later, a member of a Haitian militia ‒ or private army ‒ accused Bigio and another businessman of paying for the 1993 assassination of a prominent democracy activist, according to Jeb Sprauge, author and University of California Riverside research associate. Authorities in Haiti did not charge Bigio with or accuse him of wrongdoing.

Years later, Bigio was the subject of positive reporting when a company of his provided medical relief after an earthquake that killed an estimated 230,000 people. The Israeli government set up a hospital on property owned by the Bigio family, according to media reports at the time.

Publicly, Bigio stays focussed on making money. “Our principle, which we respect daily, is to not mix in Haitian politics,” he said in a 2007 newspaper interview.

In August 2020, Haiti’s court of auditors criticized a government deal with a company owned by the Bigio family that was scrutinized as part of a broader probe into the alleged mismanagement of more than $2 billion in state funds. The company, Repsa SA, received a $30 million dredging contract despite a government decision to limit the contract to half that price.

“Is it favoritism? Is this a poor needs assessment?” the court asked. “This way of managing development projects … has caused harm to the project and to the community.” Repsa did not respond to requests for comment.

Abdallah, 64, owns one of Haiti’s major insurance companies, and he was reportedly a close ally of a former president, Jovenel Moïse. Abdallah is the honorary consul for Italy; Bigio is the former honorary consul for Israel. Honorary consuls are part-time volunteer diplomats who receive some of the perks and protections afforded professional diplomats.

In 2018, as President Moïse came under pressure from growing unrest in the country, he reportedly sought refuge in a home owned by Abdallah. Local media reported that the home benefited from diplomatic protections given to Abdallah in his position as honorary consul. Moïse was assassinated in 2021.

‘Of the utmost integrity’

Records from the Pandora Papers show that Bigio and Abdallah were owners, directors or shareholders of at least 20 offshore companies.

While owning an offshore company is not in itself illegal, such companies are used to evade taxes and commit other crimes. Offshore companies present particular challenges for poor countries, including Haiti, where tax inspectors, police and judges often face difficulties obtaining information about the wealthiest citizens.

Bigio was connected to at least a dozen such companies, many of which were created in the Bahamas. He also set up two trusts, secretive entities that can provide tax benefits and that often do not require disclosure to governments.

The trusts were used to benefit members of Bigio’s family living in the United States, records show. One trust invested in the fuel industry. Another, the Deep Blue Trust, had a $31 million stake in Haitian companies and owned a $3 million home in the Bal Harbour enclave in Miami-Dade County.

One of Bigio’s most active helpers was the Miami-based law firm Packman, Neuwahl & Rosenberg. “My firm has been doing business with Gilbert for over 10 years and we have found him to be of the utmost integrity, to be extremely moral and professional,” wrote firm co-founder Todd Rosenberg in a 2010 letter of reference as he helped Bigio open a bank account in Switzerland.

“Gilbert Bigio has always demonstrated a high degree of integrity and capability, and has been well esteemed by his colleagues and friends,” wrote Richard Bajandas, a founding partner at another Florida law firm, Perlman, Bajandas, Yevoli & Albright.

Rosenberg did not respond to requests for comment. Bajandas told ICIJ that he stands by his firm’s assessment of Bigio’s reputation.

“No evidence has ever been provided (nor to our understanding exists) that Mr. Bigio had anything to do with the gangs in Haiti,” Bajandas said, commenting on the Canadian sanctions. He added that gang violence in Haiti has caused economic harm to Bigio and his businesses.

“Pointing fingers without any proof is equally damning and is a continuation of the misinformation that has ravaged Haiti for years,” Bajandas said.

Abdallah owned at least four companies registered in the Bahamas, records show. In 2017, according to one document, Abdallah established a company in the British Virgin Islands to own a $1 million yacht named Karisa.

In setting up the company, Abdallah listed his home as a 20th-floor apartment in downtown Miami.

Not far down the road worked his longtime private bankers at Santander Bank. “In all my dealings with Mr Abdallah, I have found him to be of the highest personal integrity and honesty,” one banker wrote in 2017. “I can unequivocally state that Mr Sherif Abdallah is a person of the highest character.”

Santander Bank did not respond to requests for comment.

After Canada imposed sanctions, Abdallah resigned as a vice president of Sogebank, one of the largest financial institutions in Haiti.

‘Diplomatic power’

Bigio and Abdallah also moved together in another close-knit circle: diplomacy.

Abdallah has represented Italy as honorary consul in Haiti for more than a decade, records show. Bigio was Israel’s honorary consul in Haiti for more than twenty years; a large Israeli flag once flew outside his home, according to media reports.

The protections enjoyed by honorary consuls include the diplomat’s ability to shield certain communications and properties from searches by law enforcement officers.

In 2016, according to the Pandora Papers, Bigio and his wife, Monique, used diplomatic passports to help set up an offshore company.

Honorary consuls do not automatically receive diplomatic passports, but some countries provide them. And diplomatic passports can come with travel benefits, including special treatment by customs officers and police at airports.

“Many of those who dominate the economy in Haiti are also honorary consuls,” said university professor Jean-Vernet. “Police won’t search their homes or their places of work because they believe them to be protected as part of the honorary consulate. They have diplomatic power.”

Ben Moore, a spokesperson for Israel’s foreign ministry, said it vets the background of all its honorary consuls but declined to comment on why it had appointed those previously sanctioned by the United States. Moore said Bigio’s son, Reuven, replaced his father as honorary consul more than a decade ago.

The foreign ministry in Italy told ICIJ media partner, L’Espresso, that it promptly learned of the sanctions against its honorary consul, who chose to “self-suspend” himself from the role. Italy is now seeking an honorary consul in Haiti to replace Abdallah.

Contributors: Leo Sisti (L’Espresso, Italy)