A business executive in Luxembourg behind a successful effort to roll back corporate transparency in Europe owned companies in high-profile tax havens, leaked documents show.

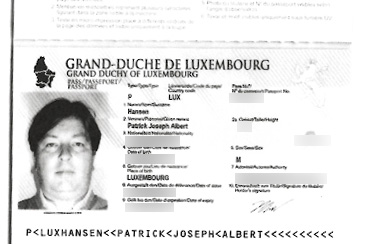

Patrick Hansen, 50, was one of two plaintiffs who last week persuaded the highest court in Europe to rule that making public the names of company owners violates personal privacy and the right to the protection of personal data.

Records from the 2021 Pandora Papers investigation show Hansen owned a holding company in the British Virgin Islands with activities in Luxembourg, Cyprus and Russia and assets valued at more than $3 million. Hansen also co-owned a company registered in the Central American tax haven of Belize, records show.

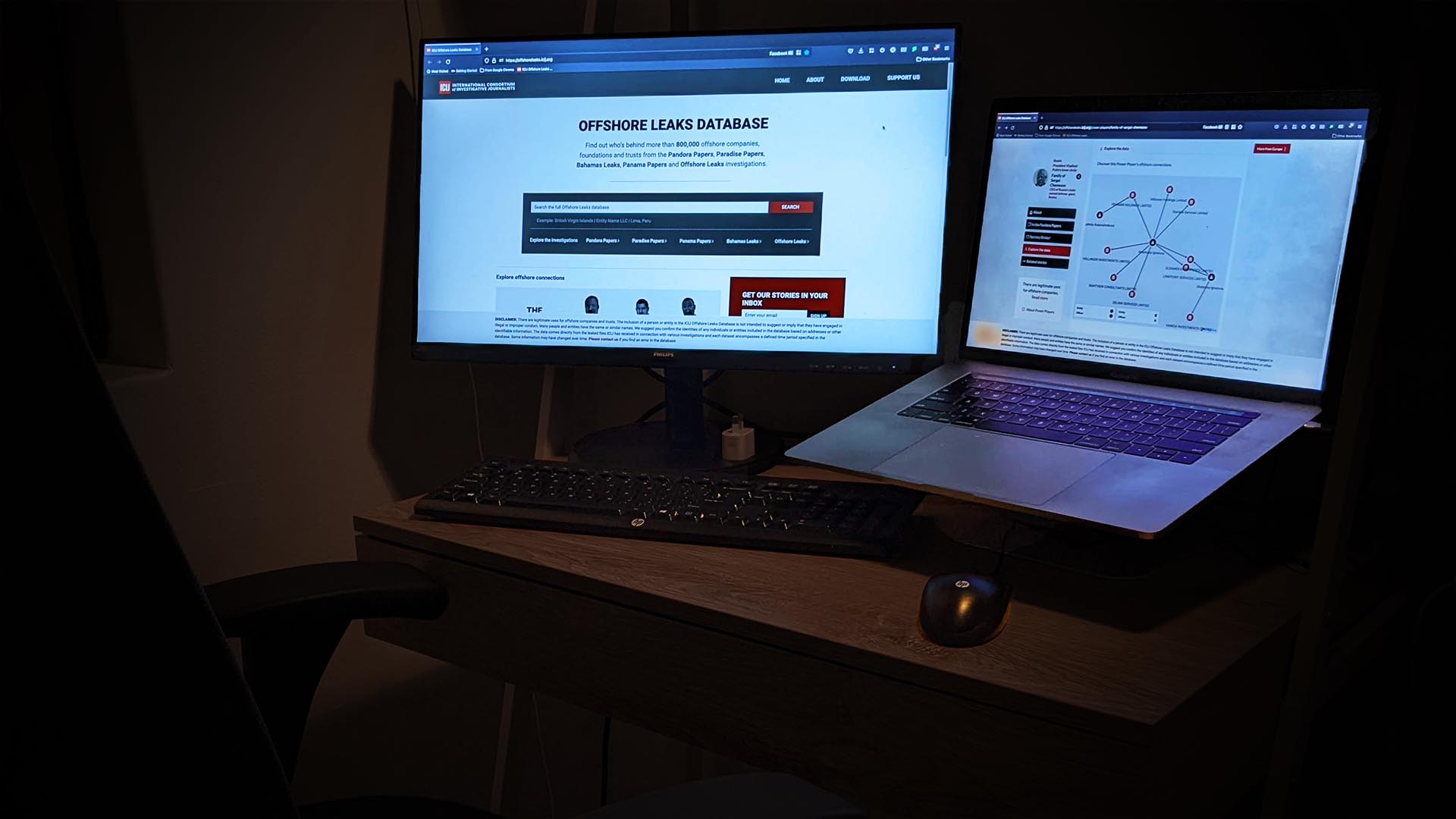

The Nov. 22 ruling from the Court of Justice of the European Union struck down a 2018 requirement that member states establish and publish databases of company owners. In recent years, those databases have allowed journalists, lawyers and members of the public to better identify whose money is flowing into shell companies and other vehicles for corporate secrecy.

Transparency advocates, many of whom have long pressed governments to adopt public registries, immediately criticized the ruling.

“Access to beneficial ownership data is vital to identifying – and stopping – corruption and dirty money,” Maíra Martini, an anti-corruption expert at Transparency International, said in a statement. “The court’s decision takes us back years.”

Following the ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria and Belgium announced suspensions to websites that had hours earlier allowed members of the public to identify the owners of companies registered in those countries.

The transparency rollback across Europe came even as other regions have embraced public databases of company owners. Governments in Latin America, Africa and Asia have in recent years introduced ownership registries, in some cases citing revelations from investigations into offshore finance by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

“The European Court of Justice’s decision ignores all the lessons learned over the past decade from leaks like the Pandora Papers and Panama Papers,” Moran Harari, a senior researcher at Tax Justice Network, said in a statement, calling on governments to open a hearing on the judgment.

Lawsuit challenged transparency reforms in tax haven

The court issued the decision following a lawsuit brought by Sovim S.A. and an individual who went by the initials W.M. The Luxembourg Times subsequently identified W.M. as Patrick Hansen, chief executive of private jet company, Luxaviation. Hansen co-founded the company in 2008 alongside Nicolay Bogachev, a former Soviet KGB officer, according to media reports. Bogachev is no longer involved with the company.

As part of the lawsuit in Europe, Hansen and Sovim S.A. successfully argued that Luxembourg’s public registry, established following a European Union requirement for member states to grant public access to company ownership information, exposed company owners to risks of “fraud, kidnapping, blackmail, extortion, harassment, violence or intimidation.”

The British Virgin Islands and Belize have for years been criticized for their lack of transparency by anti-corruption campaigners, tax inspectors and law enforcement officials.

Hansen did not respond to requests for comment.

Filippo Noseda, an attorney who helped lead the case against the public registry, said in a statement after the ruling that the judgment “represents a victory for data protection and the Rule of Law in an extremely politicized context.”

Noseda’s firm, Mischon de Reya, has previously represented clients with a long track record of corporate secrecy, including Dan Gertler, an Israeli businessman sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department for his alleged involvement in corruption.

Luxembourg, a tiny tax haven in the heart of Europe, has long played an outsized role in corporate secrecy.

In 2014, ICIJ and media partners revealed that Luxembourg had signed secretive deals that allowed multinational corporations to slash tax bills. Two years later, as part of the Panama Papers investigation, reporters revealed secretive offshore wealth and deals of politicians around the world, including in Luxembourg.

“Public access to beneficial ownership information can lead to more investigations by public authorities,” Transparency International said in a recent brief submitted to the same European court as part of a separate lawsuit, citing the Panama Papers investigation.

Governments have used revelations from the Panama Papers to identify and prosecute citizens who owned secretive companies, recouping more than $1.36 billion in unpaid taxes, fines and other penalties as of 2021.