The Denver Art Museum is preparing to return four antiquities to Cambodia following a news media collaboration that reported the pieces are linked to a man charged with trafficking looted artifacts.

The four antiquities to be returned came to the museum through Douglas Latchford, who in 2019 was indicted by U.S. prosecutors after decades of alleged trafficking in looted artifacts from the Khmer empire, which flourished in Southeast Asia a thousand years ago.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the Washington Post and other media organizations in the Pandora Papers collaboration began contacting museum officials about pieces in their collection linked to Latchford in July and followed up with letters in September. The museum removed the four artifacts from its collection after receiving a letter from the news organizations seeking comment about the items.

“The museum is now working with the government to return the pieces to Cambodia,” museum spokesperson Kristy Bassuener said in an email.

The collaboration reported that 10 museums around the world held at least 43 relics that passed through the hands of Latchford or those of his associates identified by prosecutors.

The four relics from Denver are of “extraordinary cultural significance,” said Bradley J. Gordon, one of the lawyers representing the Cambodian Ministry of Culture.

Gordon is part of a team the ministry assembled to track down pieces looted from Cambodia during the decades of tumult around a civil war and the genocidal regime of Pol Pot.

While the Cambodian officials said they welcomed the Denver announcement, the protracted negotiations over the four pieces reflect the general reluctance of museums to return Khmer artifacts that Cambodian officials assert were stolen from the country.

As far back as nine years ago, the Latchford pieces at the Denver museum were highlighted by a blog devoted to looted antiquities. Latchford had not been indicted at that point, but the blog, Chasing Aphrodite, noted that prosecutors had linked him to other allegedly looted pieces.

After Latchford was indicted in 2019, officials with the Denver Art Museum contacted Cambodian officials about the four pieces but, according to Gordon, the museum “did not agree” to return them. Cambodian officials also requested ownership records for all of the museum’s Khmer Empire relics.

“To date, we received no response to our request for these records,” Gordon said.

The decision by the Denver museum was earlier reported by the Colorado Sun, and that is where Cambodian officials learned of the announcement, Gordon said.

One of the four relics to be returned — a prehistoric bell — likely belongs to a set of 12 that had been looted from Prasat Province, north of the capital Phnom Penh, experts say. According to the Cambodian team’s research, Latchford likely owned at least half of the stolen set, Gordon said.

“When you put them together they made different sounds, and it is believed that they were used to call warriors to battle,” said Gordon. “Now they are spread around the world, which means it’s impossible for musicologists to study them.”

Another one of the relics to be returned is a sandstone Prajnaparamita, the goddess of transcendent wisdom — one of the antiquities named in the Pandora Papers investigation. According to a 2019 indictment, Latchford gave the museum documents with conflicting ownership history at the time of the relic’s acquisition in 2000.

One document stated that Latchford had purchased the piece from a man identified in the indictment as the “false collector.” Another document showed that Latchford had been in possession of the relic five years earlier.

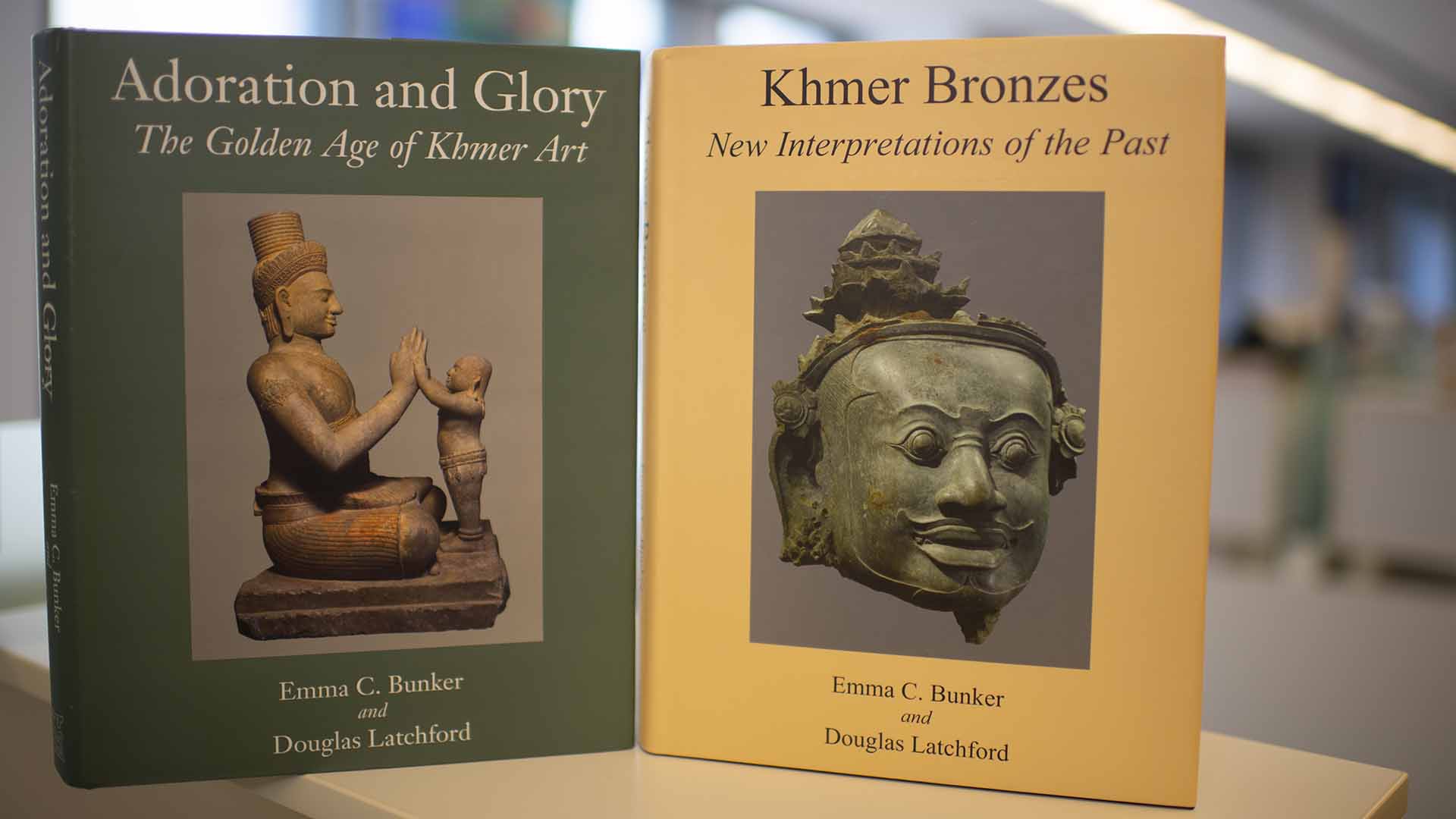

According to an archived page on the museum’s website, the Prajnaparamita had been purchased in honor of the late Emma C. Bunker, a scholar who co-authored three books with Latchford.

The two other relics that will be returned include a sun god, and a lintel with carvings of the Hindu gods Vishnu and Brahma. Both relics were published in one of Latchford’s books — a technique that prosecutors said he used to give looted items an air of legitimacy to ease their sales.

Other museums said that as needed, they continue to investigate the ownership histories of the objects in their collections that have Latchford links. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example, holds 12 pieces directly linked to him. In 2013, it returned two pieces to Cambodian officials.

“The Met has long been reviewing objects that came into the collection via Douglas Latchford and his associates,” a statement from the Met said, noting the previous return and ongoing research. “As we continue our research, we will continue this approach, as is appropriate.”