The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ exploration of the secretive world of offshore companies and trusts began after a computer hard drive packed with corporate data and personal information and e-mails arrived in the mail.

Gerard Ryle, ICIJ’s director, obtained the data trove as a result of his three-year investigation of Australia’s Firepower scandal, a case involving offshore havens and corporate fraud.

The offshore information totaled more than 260 gigabytes of useful data. ICIJ’s analysis of the hard drive showed that it held about 2.5 million files, including more than 2 million e-mails that help chart the offshore industry over a long period of explosive growth. It is one of the biggest collections of leaked data ever gathered and analyzed by a team of investigative journalists.

The drive contained four large databases plus half a million text, PDF, spreadsheet, image and web files. Analysis by ICIJ’s data experts showed that the data originated in 10 offshore jurisdictions, including the British Virgin Islands, the Cook Islands and Singapore. It included details of more than 122,000 offshore companies or trusts, nearly 12,000 intermediaries (agents or “introducers”), and about 130,000 records on the people and agents who run, own, benefit from or hide behind offshore companies.

When ICIJ further analyzed the data using sophisticated matching software, it found that about 40 percent of files and emails were duplicates.

The people identified in ICIJ’s analysis of the data are shareholders, directors, secretaries and nominees of companies and trustees, “settlors” or “protectors” of offshore trusts, as well as power-of-attorney holders who direct the actions of third parties. Many of the structures are designed to conceal the true ownership and control of assets placed offshore. Their identified addresses are spread across over more than 170 countries and territories.

A large number of positions are held by so called “nominee directors,” whose names appear again and again, sometimes in hundreds of companies. Nominee directors are people who, for a fee, lend their names as office holders of companies they know little about. It is a legal device widely utilized in the offshore world – akin to having your motor vehicle registered in the name of a stranger.

The records indicated that company directors and shareholders were often nominee companies, law firms or other types of “corporate persons,” some of which were managed and owned by still other nominees and companies.

ICIJ’s data analysis showed that the people setting up offshore entities lived most often in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Another important group of clients comes from Russia and former Soviet republics. This helps explain why the second-largest source of capital investment flowing into China is the tiny offshore tax haven of the British Virgin Islands. Similarly, a large source of investment flowing into Russia is from Cyprus, a country that also features heavily in the data – and whose financial stability was recently undermined by a crisis precipitated by Cypriot-based banks being bloated by Russian money.

ICIJ’s team of 86 investigative journalists from 46 countries represents one of the biggest cross-border investigative partnerships in journalism history. Unique digital systems supported private document and information sharing, as well as collaborative research. These included a message center hosted in Europe and a U.S.-based secure online search system. Team members also used a secure, private online bulletin board system to share stories and tips.

The project team’s attempts to use encrypted e-mail systems such as PGP (“Pretty Good Privacy”) were abandoned because of complexity and unreliability that slowed down information sharing. Studies have shown that police and government agents – and even terrorists – also struggle to use secure e-mail systems effectively. Other complex cryptographic systems popular with computer hackers were not considered for the same reasons. While many team members had sophisticated computer knowledge and could use such tools well, many more did not.

Tackling the data

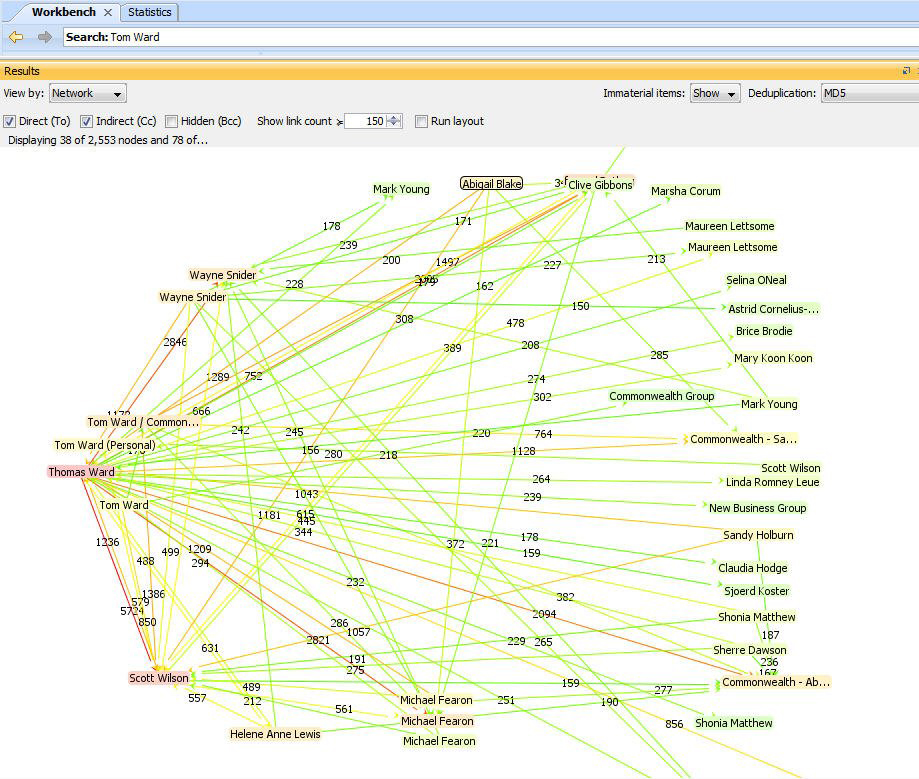

Analyzing the high volume of information was the team’s first and central challenge. With this much data, relevant information, and good stories, cannot be found just “going and looking.” What’s needed is to use “free text retrieval” (FTR) software systems.

Modern FTR systems can work with huge volumes of unsorted data, many times larger than even in this landmark investigative project. They pre-index every number, word and name, making it possible for complex queries to be completed in milliseconds. The searches are akin to using advanced features on Google or other internet search engines but are more sophisticated – and, critically, are private and secure.

The use of FTR, as well as relevant features such as timelines that tools can extract and display, have been critical to the success of the project. It sounds complicated, but still boils down to asking one of the most important questions that investigative journalists ask: “Who knew what, when?”

In their modern form, high-end FTR and analysis systems have been sold for more than a decade, in large quantities, to intelligence agencies, law firms and commercial corporations. Journalism is just catching up. Many of the tools are too expensive for most journalism organizations and may be too sophisticated for most to use. Perhaps the best-known intelligence analysis system, i2 Analysts Notebook, has been used by very few journalists or news organizations.

The major software tools used for the Offshore Project were NUIX of Sydney, Australia, and dtSearch of Bethesda, Md. NUIX Pty Ltd provided ICIJ with a limited number of licenses to use its fully featured high-end e-discovery software, free of charge. The listed cost for the NUIX software was higher than a non-profit organization like the ICIJ could afford, if the software had not been donated.

Computer programmers in Germany, the UK and Costa Rica designed sophisticated data mining and cleaning software for ICIJ to support data research. Before it was used, though, manual analysis had established much country-by-country identification of clients and thus provided an initial look at the scope and range of clients. This painstaking work was done in New Zealand and it proved crucial in early decisions on what countries ICIJ needed reporters to work in.

ICIJ’s online search and retrieval system – named Interdata – was developed and deployed by a British programmer in less than two weeks in December 2012 to support an urgent need to get relevant documents and files out faster for research by dozens of new journalists who were joining the expanding Offshore Project.

Interdata allowed team members to access and download copies of any of the offshore documents that were relevant to their countries and interests. Journalists using the Interdata system have to date made over 28,000 online searches and downloaded more than 53,000 documents.

Unreadable documents

Before loading Interdata or using NUIX or similar analysis tools, the team’s data experts had to deal with a major problem affecting tens of thousands of the leaked documents. Computers could not automatically read them because they were photographs or other images that do not contain text.

The solution was large scale re-scanning of unreadable files by optical character recognition (OCR) software that identifies and writes in the names and numbers on top of the images. This brought to the surface dozens of important new documents, including passports, contracts and letters explaining how companies were controlled.

ICIJ’s offshore 260-gigabyte data collection is more than 160 times larger in size as measured in gigabytes than the U.S. State Department cables leaked to and published by Wikileaks in 2010. The formats of the data that ICIJ’s team worked with were more complex and diffuse than the collected U.S. State Department cables passed to Wikileaks, and needed more levels of analysis.

One specially built program has been prepared to check and match names and addresses, and has spotted thousands of cases where the same person’s data has been entered numerous times in different ways for different companies. Another special program identifies the country associated with each person and company, even when geographic data has not been entered fully or correctly.

Unlike the U.S. cables and war logs released by Wikileaks, the offshore data was not structured or clean. As delivered, it consisted of a large and mainly unsorted collation of company and trust documents and instructions, e-mails, large and small databases and spreadsheets, personal identity documents, accounting information and agents’ and companies’ internal papers and reports.

As might be expected in any office computer network, many documents and e-mails had been shared and copied many times over. Some of the programs ICIJ used could automatically sift out duplicates, but others could not.

Large databases detailing offshore companies and the people who had set up and operated them were found in the data. Over three months, ICIJ recovered and rebuilt the databases in an effort to run them in their original format. When the database reconstruction was done, there were surprises. The databases had been built to record and check who really lay behind each company and trust, as required by international regulations on money laundering and “due diligence.” ICIJ’s journalists hoped the data as to who was behind a company was a click away.

In fact, database entries for “beneficial owners” were often empty. Often too, the offshore services providers had passed the legal responsibility for holding the information to intermediaries in other countries who had brought the client to the service provider. The lesson was that the empty fields were not an accident; it was the design.

A frustrating but rewarding road

In the rebuilt databases, researchers were excited by occasional electronic flashes. Sometimes, on accessing a company record, an alert screen popped up over the registered data, giving a name and contact details for the person or persons who really owned the company and its assets. A further feature in one database masked a deeper layer of secrecy, identifying thousands of people as hidden stand-ins.

ICIJ’s fundamental lesson from the Offshore Project data has been patience and perseverance. Many members started by feeding in lists of names of politicians, tycoons, suspected or convicted fraudsters and the like, hoping that bank accounts and scam plots would just pop out. It was a frustrating road to follow. The data was not like that.

But persistently following leads through incomplete data and documents yielded some great rewards: not just occasional and unexpected top names, but also many more nuanced and complex schemes for hiding wealth. Some of the schemes spotted, although well known in the offshore trade, have not been described publicly before. Patience was rewarded when this data opened new windows on the offshore world.

Duncan Campbell (U.K.), a founding member of ICIJ, is the ICIJ Data Journalism Manager for the Offshore Project and a contributing journalist. Programmers Sebastian Mondial (Germany), Matthew Fowler (UK), Rigoberto Carvajal and Matthew Caruana Galizia (Costa Rica) provided custom software design, programming and data support. The initial manual analysis of the client names was done by ICIJ member Nicky Hager and Barbara Mare (New Zealand). ICIJ member Giannina Segnini oversaw the work in Costa Rica.