INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM

Latin American journalists defy emboldened threats to press freedom in 2021

ICIJ partners in the region endured surveillance, raids, exile, smear campaigns by top politicians, laws targeting independent media and more.

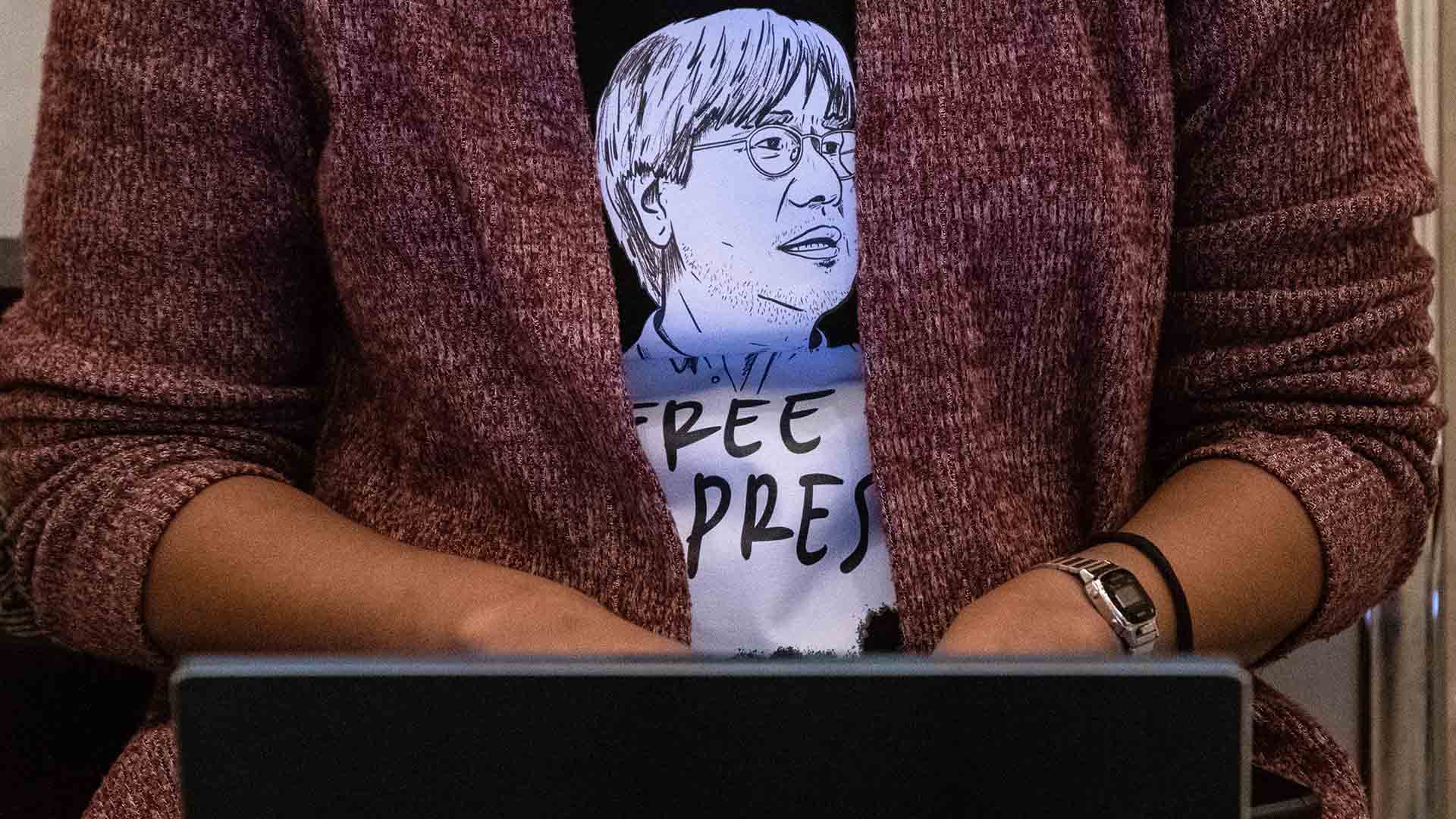

This spring, renowned Mexican journalist and ICIJ member Marcela Turati made a shocking discovery: she had been extensively surveilled by authorities amid her years of investigating the ongoing crisis of massacres and disappearances in Mexico.

From covering migrant murders to clandestine graves, Turati has stayed on top of the stories of those caught in the crossfires of turf wars between drug cartels that operate with impunity, sometimes with the complicity of police forces. Her 2015 series detailed how the process of identifying bodies found in mass graves was botched by the federal attorney general’s office. The AG, in turn, secretly opened a new file to investigate the journalist, records later revealed.

Investigators tracked the calls and text messages of Turati, as well as a lawyer for victims’ families and a forensic specialist, and traced their coordinates for more than a year. Authorities labeled them as suspects of organized crime and kidnapping in order to obtain phone records.

In May, after a years-long public records battle and an order from the Mexican supreme court to release the files, Turati and the other people targeted were able to review the documents in which they were listed as suspects.

The experience has left Turati traumatized and angry. Being spied on by their own government adds to a myriad of challenges already faced by journalists in Mexico, one of the most dangerous places in the world to practice the profession. The country remains one of the top ten deadliest for reporters with some of the highest impunity rates for crimes against members of the press. Thirty-six journalists were murdered there in the past decade, according to an annual index compile by the Committee to Protect Journalists.

“What angers me most is that, in Mexico, more than 20 people disappear daily and when family members ask that authorities track their phones to find them it takes months, if they do it at all,” Turati said. “Yet, in this case they found the resources to do … what they don’t do for the people.”

The risks of reporting in Mexico are among the most alarming signs of eroding press freedom in Latin America, where journalists have been murdered, jailed, restricted from accessing public information, and systematically harassed through social media campaigns this year. In several countries, governments limited or tried to criminalize funding for independent media. Yet, Latin America reporters, including many members of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and partner media outlets, have defied threats and censorship by continuing to publish work that exposes abuses and holds the powerful accountable.

Spying on cell phones

This year, several investigative reporters in Mexico and El Salvador found out their phones may have been infected with spyware to track their conversations and even access the phones’ cameras and microphones.

One of them was Turati, who learned in July that she might also have been under surveillance in a separate operation during the government of President Enrique Peña Nieto. Her name was on a list of journalists allegedly targeted by governments with the Israeli-made spyware Pegasus. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador – whose associates were also allegedly targeted when he was a political candidate – said the current government is not spying on journalists. But Turati and others remain doubtful and insist that authorities should formally close any pending investigations.

“It is so concerning, this poses many questions for investigative journalism,” Turati said. “How are we going to do our job? How can we protect victims who want to tell their stories or sources inside the government who want to expose wrongdoing? What will happen if they are discovered?”

Turati was not the only ICIJ partner affected in the region. In November, journalists from six media outlets in El Salvador, including 12 staff members of ICIJ partner El Faro, received an email from Apple warning that “attackers sponsored by the State”, might be spying on them through their cell phones. Apple sent the notification the same day it sued NSO Group, the Israeli company that created Pegasus, according to media reports.

NSO Group has insisted that Pegasus was developed to combat terrorism and organized crime, not to spy on journalists and dissidents. But journalism investigations exposed how the software has been used by governments to spy on reporters and critics. For Salvadoran journalists, the alert was the latest blow in a series of escalating government attacks.

Journalists under siege in El Salvador

This year, El Salvador experienced the steepest fall in Reporters Without Borders’ annual press freedom index. The group reported that officials harass and threaten journalists investigating corruption and some of the attacks come directly from the country’s president.

“Nayib Bukele has attacked and threatened journalists critical of his government, has blocked many of them on social media, and has used the extremely dangerous tactic of trying to portray the media as an enemy of the people,” Reporters Without Borders said.

#HumanRights | The @CIDH has determined that @_elfaro_ has been subject to harassment, threats & stigmatization in its journalistic endeavors, issued protective measures, & called on the Salvadoran state to preserve the “life and safety” of El Faro staff.https://t.co/iSZBqnlL4w

— El Faro English (@ElFaroEnglish) February 5, 2021

Last year, Bukele announced that El Faro was allegedly under investigation for money laundering, prompting more than 600 journalists and intellectuals from 47 countries to send a letter to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in defense of the outlet. Meanwhile, El Faro has been placed under extraordinary audits by the country’s finance authorities since September 2020, a process that started as the outlet was preparing to publish an investigation detailing how Bukele negotiated prison benefits with the criminal organization MS-13, in exchange for both a reduction in homicides and electoral support. Bukele denied having negotiated with the gangs and called El Faro a “pamphlet.” The outlet’s leaders have called the audits “aggressive,” saying tax officials are requesting communication exchanges with donors, years of meeting minutes and information for all subscribers.

Reporters pushed out

El Faro experienced further challenges this summer when editor and ICIJ member Daniel Lizárraga was expelled from El Salvador to his native Mexico after authorities denied him a work permit. El Salvador also denied a work visa to Roman Olivier Gressier, an El Faro journalist from the United States.

Other ICIJ partners have also been expelled or had to flee Latin American countries.

Leading Nicaraguan journalist and ICIJ member Carlos Fernando Chamorro announced on Twitter in June that he left his country to “preserve his freedom” amid escalating repression and imprisonment of journalists, presidential candidates and critics of the Ortega regime, leading up to the November presidential elections. One of the presidential candidates under house arrest since June is Cristina Chamorro, Carlos Fernando Chamorro’s sister.

Carlos Fernando Chamorro, currently residing in Costa Rica, said that police officers were harassing his family members and surveilled the house of his mother, former Nicaraguan president Violeta Barrios de Chamorro. The day before he left his country, his home was raided by police. In recent years, police forces have raided the newsroom of his outlet, Confidencial, at least two times. Chamorro previously had to leave Nicaragua in 2019 after another newsroom raid.

EXIJO QUE CESE EL ASEDIO POLICIAL/1 . Mi esposa Desirée Elizondo y yo salimos de Nicaragua, para resguardar nuestra libertad. Hacer periodismo y reportar la verdad no es un delito. Seguiré haciendo periodismo, en libertad, desde fuera de Nicaragua.

— Carlos F Chamorro (@cefeche) June 22, 2021

Also this summer, the Nicaraguan government arrested Juan Lorenzo Holmann, publisher of La Prensa, the country’s only national daily. Authorities said Holmann was held under suspicion of customs fraud and money laundering, accusations he denied. Police raided the newsroom and the customs department confiscated the paper’s newsprint, causing it to stop distribution.

At least 70 journalists have left Nicaragua and gone into exile since 2018, after a social uprising against Ortega’s government followed by an ongoing wave of media repression, according to a report published by Carlos Fernando Chamorro in November. “Freedom of expression is effectively suppressed” in Nicaragua, Chamorro told news agency EFE.

Even when journalists go into exile, their families can face hostility. This October, Roberto Deniz, a reporter at Armando.info, an ICIJ partner outlet, announced on Twitter that his relatives’ home in Caracas was raided by authorities. Deniz has been exiled in Colombia since 2018, when he and three other colleagues, two of them ICIJ members, had to leave the country. The journalists were sued by mysterious Colombian mogul Alex Saab, in an attempt to muzzle reporting that Saab reaped millions of dollars via an offshore company in Hong Kong. The company artificially inflated food prices on packages provided to Venezuela’s poorest citizens under a government-run program, according to Armando.info.

En la residencia de mis padres en Caracas está mi hermano, mi cuñada y dos sobrinas menores de edad. Alerto y responsabilizo a las autoridades venezolanas de cualquier cosa que pueda pasarles.

— Roberto Deniz (@robertodeniz) October 15, 2021

In 2019, the United States accused Saab of money laundering in connection with a bribery scheme in Venezuela. U.S. officials have privately identified him as a frontman for Venezuela’s president Nicolás Maduro, according to PBS. As the U.S. finally nabbed Saab in October and he was extradited from Cape Verde to South Florida, the Venezuelan government targeted Deniz’s relatives and issued a warrant for Deniz’s arrest on charges of “instigating hate.”

Creating laws against independent media

Shortly after the publication of the Pandora Papers, the international exposé of the offshore financial system coordinated by ICIJ, lawmakers in Honduras approved legislative reforms that could affect nonprofit news organizations. One of those is Contra Corriente, an ICIJ partner in the country.

Jennifer Ávila, the outlet’s co-founder and director, exposed the offshore dealings of two men running for president, including the ruling party’s candidate. (Both subsequently lost the election.)

Days after the Pandora Papers investigation, the National Congress approved changes to the country’s anti-money laundering rules and other laws that would designate civil society organizations that investigate, evaluate or analyze public management, including the work of the government, as “politically exposed persons,” or PEPs. The law singles out groups that receive or administer foreign aid funds, which is necessary for any nonprofit media organization in Central America, where funders of quality journalism are scarce.

Nonprofit outlets maintain editorial independence from their funders, but that hasn’t stopped some countries in Latin America from using the law to criminalize independent journalists, declaring them foreign agents or accusing them of collusion if they received international funds. The government of El Salvador is seeking to pass a law that would require nonprofit organizations who receive international funding to register as foreign agents and pay 40% in taxes for each financial transaction. The law would sink independent media and human rights organizations, its critics said.

Nicaragua approved a similar foreign agent law in 2020 and Venezuela has been criminalizing international funding for independent investigative journalism since 2010.

The politics of covering the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has “exacerbated an already complex and hostile environment” for reporters in the region, with governments trying to control the narrative, according to a Reporters Without Borders analysis. “Journalists were publicly accused of exaggerating the gravity of the health crisis and spreading panic. Those who dared question the authorities’ handling of the pandemic were arrested, accused of “disinformation terrorism” and in some cases jailed,” the report said.

A glaring example is Brazil, where President Jair Bolsonaro has tried to minimize his administration’s disastrous response to the pandemic by vilifying the media, publicly humiliating journalists and blaming them for the crisis. In February, ICIJ partner Revista Piauí published an article detailing how Bolsonaro publicly downplayed the gravity of the virus and stalled timely vaccine distribution.

Still, Latin America’s investigative journalists aren’t deterred.

Turati said she will keep coordinating adondevanlosdesaparecidos.org, a platform where a group of journalists from different regions in Mexico tell the stories of the disappeared and document the struggles of families in search of their loved ones. The platform launched in 2018, with a data project entitled The country of the two thousand graves, which includes the most comprehensive map of clandestine graves found in Mexico between 2006 and 2016. The map has become a tool for people looking for their missing relatives.

“Journalism is a kind of truth commission in real time,” said Turati, whose work has been recognized internationally with multiple awards. “In a country where justice isn’t working and impunity is the norm I feel like, in a way, we journalists are showing the authorities that these atrocities can be investigated, they just don’t want to do it.”