In early 2006, Hushang Ansary — a former Iranian statesman who immigrated to Texas to make a fortune in the U.S. oil business — strode into the Curacao headquarters of Ennia, a private pension fund and the island nation’s largest insurance company. He had just purchased the business, and employees lined the walls and clapped loudly to welcome their illustrious boss. With a wide smile, Ansary clapped, too, and bowed in a show of respect for the old hands at his new enterprise.

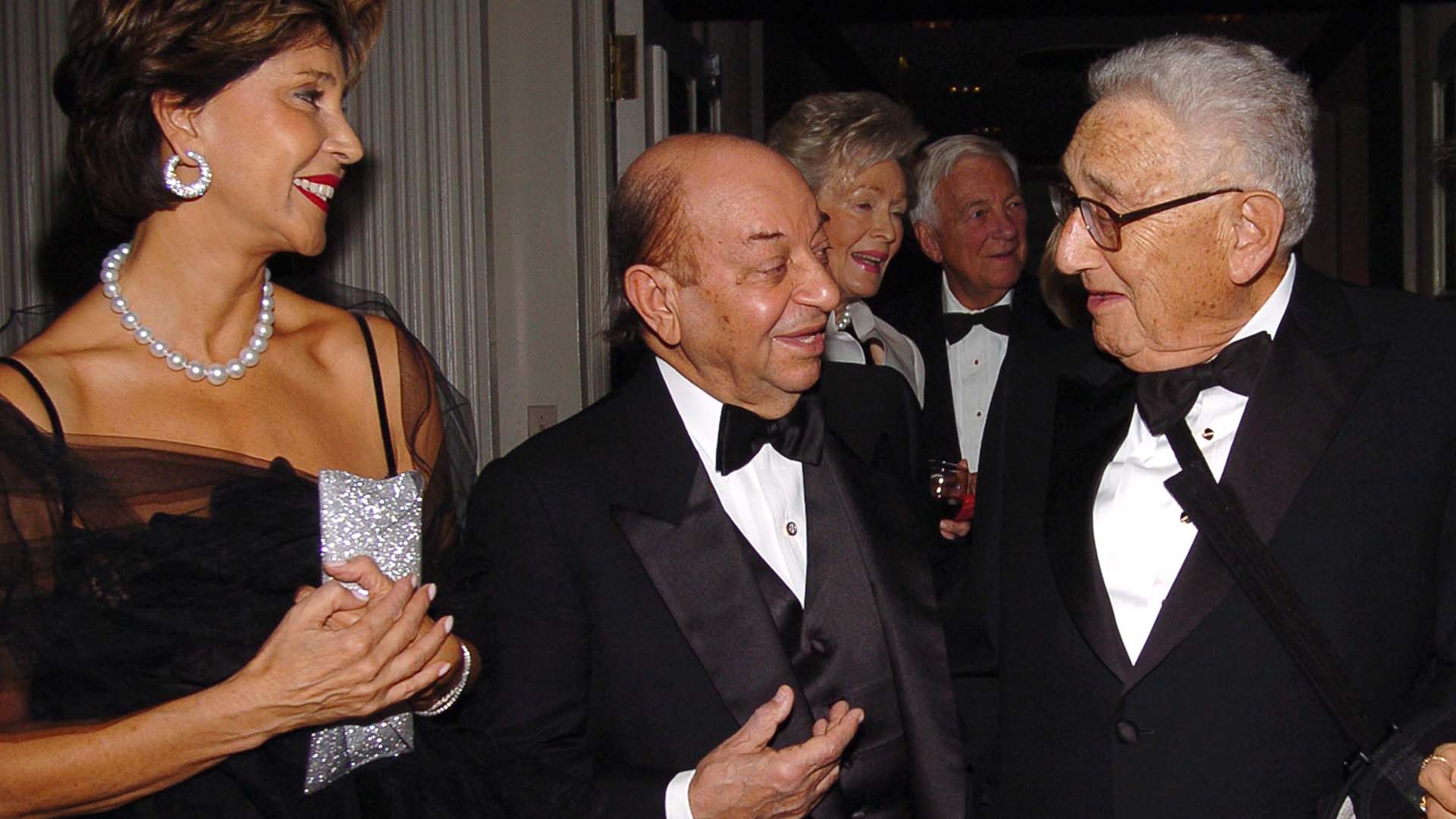

Longtime Ennia employees, though, found Ansary’s takeover curious. He was a powerful force in the United States, a major donor to Republican causes and a friend of the Bush family, Henry Kissinger and other conservative luminaries. The Texan had little known experience running an insurance and pension business like Ennia. What were his intentions?

Nearly two decades later, many more people across the Caribbean island are asking the same question.

The Central Bank of Curacao and Sint Maarten has accused Ansary of draining assets from Ennia, threatening the income of 30,000 pension holders in Curacao and neighboring islands. Authorities say Ansary used the money to invest in his other businesses, for private jet travel, to dispense millions in questionable payments to acquaintances and to send donations to conservative causes in the United States. Now the central bank is suing Ansary in Texas to recover the hundreds of millions of dollars it says he owes Ennia.

Like with most white-collar scandals, behind the high-profile names in the Ennia controversy are the accountants — often at global firms — who inspect companies’ books and create transactions of such complexity it can take years for investigators to untangle them.

The global giant KPMG, for example, audited key parts of Ennia’s business during Ansary’s reign, signing off on financial statements during its now-controversial years. But in its exploration of the Ennia turmoil, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists focused on the role of the London-based accounting giant PwC, formerly known as PricewaterhouseCoopers.

ICIJ spent hours speaking with Ansary and reviewed extensive financial records and court documents that paint a troubling picture of PwC’s role with Ennia. Six years into running the company, Ansary had PwC set up offshore shell companies. Those companies helped Ansary minimize taxes and participated in complex maneuvers that Curacao authorities later said wrongfully deprived Ennia of hundreds of millions in assets.

In 2018, the Central Bank of Curacao and Sint Maarten, which also serves as a regulator of financial businesses on the two islands, declared that Ennia was going broke and seized control of the insurer from Ansary. Even after the central bank had taken over Ennia’s day-to-day operations, PwC helped to incorporate new shell companies in Cyprus and Texas tied to Ennia — for exact reasons that, so far, no one has been able to explain to ICIJ.

Ansary, who is 96 years old, told ICIJ that he is staying healthy in his advanced age in large part so he can fight back against Curacao authorities.

He said the central bank is leading an international scheme that seeks to take his honestly earned money. “I think this is the Ponzi scheme of the century, and I cannot do anything about it,” Ansary said.

The offshore movements of Ennia-linked money are detailed in internal records of the Cyprus office of PwC. The findings are part of Cyprus Confidential, an investigation led by ICIJ and Paper Trail Media with 67 media partners. They come in large part through ICIJ’s analysis of 3.6 million leaked records that show the key role the firm played in helping Russian oligarchs and others accused of crimes and financial misappropriation.

The 3.6 million leaked files at the heart of the Cyprus Confidential investigation come from six financial services providers and a website company.

The providers are: ConnectedSky, Cypcodirect, DJC Accountants, Kallias & Associates, MeritKapital, and MeritServus in Cyprus. The MeritServus and MeritKapital records were obtained by Distributed Denial of Secrets. Leaked records from Cypcodirect, ConnectedSky and i-Cyprus were obtained by Paper Trail Media. In the case of Kallias & Associates, the documents were obtained from Distributed Denial of Secrets, which shared them with Paper Trail Media and ICIJ. DJC Accountants’ records were obtained by Distributed Denial of Secrets and shared by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. The partner organizations shared all the leaked records in the project with ICIJ, which structured, stored and translated them from several languages before sharing them with journalists from around the world. Additional records came from Latvia-based Dataset SIA, which maintains the i-Cyprus website, through which it sells information about Cyprus companies, including Cyprus corporate registry documents.

Citing client confidentiality, PwC declined to answer detailed questions about its work with Ansary and the shell companies. But in an email to ICIJ, PwC spokesman Mike Davies said that the firm strives to maintain the highest professional ethics. “PwC’s internal standards are reviewed and updated to reflect both lessons learned and changing circumstances,” Davies wrote, “and we do not hesitate to take action when our standards are not met.”

Meanwhile, in Curacao, many thousands are awaiting definitive action. Ralph Koch, a 77-year-old former teacher and government worker, said that if he loses his Ennia pension income he will survive, but what bothers him most is the sense of unfairness.

“The people [at] Ennia took the money,” Koch said. “That’s the pain I have from this situation.”

A winding path to prosperity

Ansary was born in 1927 to middle-class parents living in Iran’s coastal Khuzestan province, far from the country’s power center of Tehran. His father, a bank clerk who had studied in India, taught Ansary to look outside Iran for his destiny. “I’d like you to leave this country as fast as you can,” Ansary recalls his dad telling him. After school on Fridays, Ansary’s father had him take typing classes that used English-language typewriters, Ansary said. “He would tell us: English, English, English.”

In his early years, Ansary’s gift for mastering languages landed him jobs with foreign wholesalers shipping goods to merchants in the country’s sprawling bazaars, he said. In his 20s, after a stint as a correspondent covering the Soviet invasion of northern Iran for the International News Service and other international news organizations, Ansary visited Japan. He ended up spending years there. The country was in the midst of a massive economic restructuring after its World War II defeat. “In Japan, making money was the easiest thing in the world,” Ansary said.

When the Shah of Iran arrived in Japan for a state visit, he was impressed by the young Iranian and invited Ansary to come back to Iran to join his government. Ansary agreed, and in less than a decade he vaulted through the ranks of Iran’s ruling class, a fast ascent that commentators could attribute only to a legendary intellect and a sharp instinct for locating and seizing opportunity.

“His mind was more agile than erudite, his determination was relentless, and his generosity was calculated,” wrote Abbas Milani in his book “Eminent Persians: The Men and Women Who Made Modern Iran, 1941-1979,” published in 2008. “He had a knack for surrounding himself with good lieutenants and assistants and, though he was a stern and demanding task master, he showered those around him with gifts and bonuses.”

In 1967 Ansary became Iran’s ambassador to the United States. By 1975 he had advanced to finance minister. That year, wearing a plaid necktie and sitting next to Kissinger, President Richard Nixon’s secretary of state, Ansary signed a major deal that included an agreement for the U.S. to help Iran develop nuclear energy. The following year Ansary made headlines when he projected that the U.S. would soon “occupy the first position among Iran’s trading partners.”

As Kissinger and Ansary orchestrated a major arms and trade deal, The New York Times pointed to their relationship “as underscoring the growing political, economic and military ties” between Washington and Tehran.

In 1977, Ansary took the helm of Iran’s national oil company, cementing his place as one of the most powerful men in the country. But in another show of intuition, Ansary resigned his post in 1978 and left the country just months before a revolution unseated the shah. He ended up in Houston, the heart of a booming Texas oil industry, where he had made powerful friends. They were apparently eager to work with the wealthy new arrival who had a penchant for getting things done.

One of Ansary’s new ventures included going into business with Kissinger and Frank Carlucci, who would later become President Ronald Reagan’s defense secretary. In the early 1980s, Ansary invested in a Caribbean resort and casino on a piece of beachfront land in St. Maarten, a former Dutch colony with close ties to Curacao. Kissinger would sit on the board, and Carlucci would become a part owner.

Ansary, who has become a U.S. citizen, told ICIJ that his interest in doing business in the Caribbean was motivated by goodwill toward U.S. allies rather than profits. “The idea was not to go and make money on the islands,” he said, adding that he wanted to take money he made in the U.S. “and allocate a portion of it for job creation and job security and economic benefit to these islands. The intention was to give them a helping hand.”

The new boss

Part of the Netherlands Antilles group of islands, Curacao is a former Dutch colony that, along with St. Maarten, was granted independence in 2010. Although now autonomous, Curacao remains a part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, which helps oversee the island’s national defense and foreign relations. Curacao’s central bank, which also regulates financial institutions in St. Maarten, is tasked with keeping tabs on major insurance and pension firms like Ennia.

In the world of global finance, nothing seemed wildly out of the ordinary about Ansary’s takeover of the firm in 2006, although some Ennia employees were uneasy about being managed by Americans rather than Dutch bosses, three longtime employees told ICIJ. Also, Ansary was known as an investor, not an insurance or pension professional.

Within two years, more concrete worries about Ansary’s leadership surfaced. In 2008, Herman Couperus, an Ennia actuary responsible for assessing risks the business might face, began to notice a series of startling decisions Ansary was making as he managed the firm’s assets, Couperus told ICIJ. These assets were crucial reserves to ensure future payments to thousands of policyholders, Couperus said. Ansary’s team had created a new company under the overall Ennia group but outside the company’s insurance and pension divisions called EC Investments BV, which would hold hundreds of millions of dollars in assets. Couperus said it appeared that the company’s investments were being moved to the separate entity, and he struggled to understand why.

“It wasn’t a logical management decision for any insurer, and it wasn’t for Ennia,” he said. “There was simply no business need for it.”

Even more troubling for Couperus was how the company’s investments were being used. Ansary had transferred his St. Maarten property to Ennia, Couperus said. According to former employees, questions swirled around the deal.

“There was a clear conflict of interest,” Servaas Houben, who led Ennia’s actuarial department from 2013 to 2018, told ICIJ.

The St. Maarten property, known as Mullet Bay, could have theoretically produced good income for Ennia, except that many of its attractions were largely destroyed by Hurricane Luis in 1995 and had been closed ever since, according to court records. What Couperus and Houben say they knew for certain was that Ansary benefited from a deal in which Ennia became saddled with a damaged asset of uncertain value.

Ansary told ICIJ that, while parts of the property had been damaged, “Mullet Bay has long been St. Maarten’s most valuable asset,” and pointed to its golf course that still hosts tournaments.

By early 2010, Couperus was growing even more troubled as he examined how hundreds of millions in Ennia money had been invested into Ansary’s Houston-based Stewart & Stevenson, a manufacturer of military, oil and gas equipment, he said.

In its lawsuit against Ansary, the central bank said the Mullet Bay investment represented an “obvious conflict of interest,” alleging that Ansary overvalued the property to make excessive distributions and withdrawals from Ennia accounts. According to the central bank’s litigation against Ansary and others, by 2010 the Mullet Bay property and the Stewart & Stevenson investment accounted for most of Ennia’s assets. The central bank alleges that Ansary and his management team deprived Ennia of its rightful share of profits from the Stewart & Stevenson investment, claiming that they pocketed $509 million “with an investment of USD 5 million.”

During more than four hours of interviews with ICIJ, Ansary rejected the claims that he mismanaged Ennia funds. To the contrary, he said, he took a poorly performing firm and made it more profitable. The activities of EC Investments, the new investment vehicle he created under the Ennia umbrella, had little to do with the insurance company’s solvency, he insisted — it was simply a separate investment firm that was off Ennia’s books. Ennia could, however, benefit from lending money to the new investment firm, Ansary said.

“This was designed in order for Ennia insurance companies not to be subjected to the shocks of the marketplace,” he said. “If they have the name of ‘Ennia,’ it doesn’t mean they’re all the same company.”

In court filings, lawyers for Ansary have called the central bank’s contention that Ennia was deprived of its fair share of Stewart & Stevenson proceeds “entirely untrue, unwarranted, and baseless.” Ennia policyholders “were in no way participants” in the Stewart & Stevenson investment and that Ennia never missed a payment to its customers, according to the filings.

In July 2010, Couperus emailed Ennia’s board outlining his concerns and urging that “we do need to intervene here.” He said the alarms he raised to the firm’s senior leadership and board resulted in no lasting changes.

“At that stage, I knew management could not be stopped,” Couperus said. Shortly after that Couperus stopped working with Ennia.

Couperus wasn’t the only one calling attention to the transactions. Later that year, Ennia’s chief lawyer, Ludwig Voigt, sent a memo to management citing “a very serious, worrying and alarming situation.”

“The picture has emerged of very dominant officers” governing Ennia, Voigt added, “initiating financial transactions without any benefit to Ennia, with the management board following without any protest.”

In early 2011, Ansary, who lives in Houston but periodically visited Ennia’s headquarters in Willemstad — Curacao’s capital — convened Ennia’s senior management, according to court records. “The outcome of the meeting,” a summary of meeting minutes states, “was that Ansary made it extremely clear that he would make the investment decisions himself.”

Ansary said court records mischaracterized this meeting. He was chairman of the Ennia board, and his lawyers note that he always voted with the majority of board members, which included prominent figures such as Carlucci and former Republican politician and football player Jack Kemp.

Ansary’s time at Ennia overlapped with a period of significant political giving. Since 2006, Ansary and his wife, Shahla, have donated more than $13 million to politicians in the United States, mostly Republicans, including $2 million in donations to Donald Trump’s 2017 inauguration, according to OpenSecrets, a Washington-based research nonprofit that tracks money in politics.

In its litigation against him, the central bank accused Ansary of using millions in Ennia funds to support unrelated causes in the U.S., including contributions to George W. Bush, a foundation associated with the Bush family, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston.

A spokesperson for the Museum of Fine Arts said Ansary had donated but that Ennia was not a donor. Ansary said that EC Investments, the Ennia investment firm he set up, never made a political donation in the United States.

One manager who spent decades at Ennia told ICIJ that upper management instructed him to wire a $1 million donation to the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library. The former manager, who asked to remain anonymous to avoid business repercussions on the small island, said he carried out the order but added: “I never got an explanation for this.”

The George & Barbara Bush Foundation, which receives private donations for the Bush library, did not respond to multiple requests to comment on the donation.

“Our business had absolutely nothing to do with the United States,” the former Ennia manager said. “It was strange. It was part of a lot of strange things I saw.”

A partner in secrecy

As a Big Four accounting firm, PwC is a key player in the global financial system, performing audits and other services for some of the world’s largest companies. It has also brought some of the world’s wealthiest citizens on as clients. In some cases that has led to major legal and ethical lapses.

A 2014 ICIJ investigation revealed how PwC Luxembourg helped giant companies shift profits around the globe to slash billions from their tax bills. Six years later, ICIJ detailed the way the firm disregarded accounting red flags to work with Isabel dos Santos, an Angolan billionaire who had reportedly engaged in corrupt deals.

Last week, ICIJ published a wide-ranging project looking at the Cyprus office of PwC and its role in Russia’s wartime financial machine, including moving money for oligarchs and figures involved with President Vladimir Putin’s military operations. The firm’s Cyprus operations also helped those outside Russia, including tyrants and criminals, around the world.

In 2012, amid internal alarms being raised at Ennia, Ansary turned to PwC to help construct a set of shell companies owned by EC Investments.

“PricewaterhouseCoopers was brought in by us because, number one, they were the largest accounting firm in the world,” Ansary said, adding that the offshore companies were used to navigate global taxation treaties. “We had no tax obligations in Curacao as a result of that network.”

PwC administered one of the firms in Cyprus that owned a shell company in Luxembourg, a well-known destination for clients seeking low taxes and secrecy. The firms held more than a hundred million dollars in the Stewart & Stevenson investment. Curacao officials later alleged that this investment was the subject of complex manipulation by Ansary and others that deprived Ennia of hundreds of millions in proceeds.

At first, few knew about the shell companies, according to former Ennia employees. Houben, from the actuarial department, said he was surprised to learn Ansary’s team had created a stack of offshore shell companies within Ennia’s already complex corporate structure. But what was most surprising to Houben was how he learned about the shell companies — from news reports.

“We were left in the dark,” Houben said. “Myself and the risk manager should have been aware of those things. It’s crucial to know what’s happening on the asset side.”

In June 2016, news outlets in Curacao and the Netherlands reported that the government of the Netherlands, where Ennia has some operations, believed Ansary siphoned money out of the company, leaving a major deficit in Ennia’s core business and threatening tens of thousands of pensions. Regulators had begun closing in on the firm.

On July 4, 2018, alleging Ennia was nearing collapse due to Ansary’s withdrawals, Curacao’s central bank seized Ennia’s insurance and pension business in an attempt to stop the outflow of cash. The central bank took over the day-to-day operations of the firm and began hunting for the money that it believed belonged to Ennia.

Ansary asserts that Curacao authorities took over his company illegally, depriving him of due process under Curacao law. He said that the central bank stacked the deck against him, presenting him with hundreds of pages of court records in Dutch just minutes before hearings.

The central bank began to seize assets it argued belonged to the firm. On Jan. 22, 2019, central bank officials told a bankruptcy judge in Manhattan that the situation was urgent. “We would go under” if the negative cash-flow problem isn’t fixed, an Ennia officer told the judge. Days later, the judge ruled in the central bank’s favor, granting Ennia access to some $240 million in accounts associated with Ansary.

The money would strengthen Ennia’s business, including payments to its pension holders in the short term. Curacao authorities would say, though, that much more needed to be recovered from Ansary and others to keep the business afloat for decades to come.

The Texas branch

In late 2018, with Ennia’s business operations under central bank control, PwC oversaw a series of strange transactions connected to the company. At the time this story was published, ICIJ had not found anyone who could or was willing to explain these transactions.

In December 2018, PwC registered a new Cyprus shell company linked to Ennia called Onafield Ltd., a secretive appendage to Ennia’s preexisting offshore structure. It remains unclear who directed Onafield to be incorporated.

In its public filings, Onafield’s only officers are Cyprus-based stand-in directors affiliated with PwC.

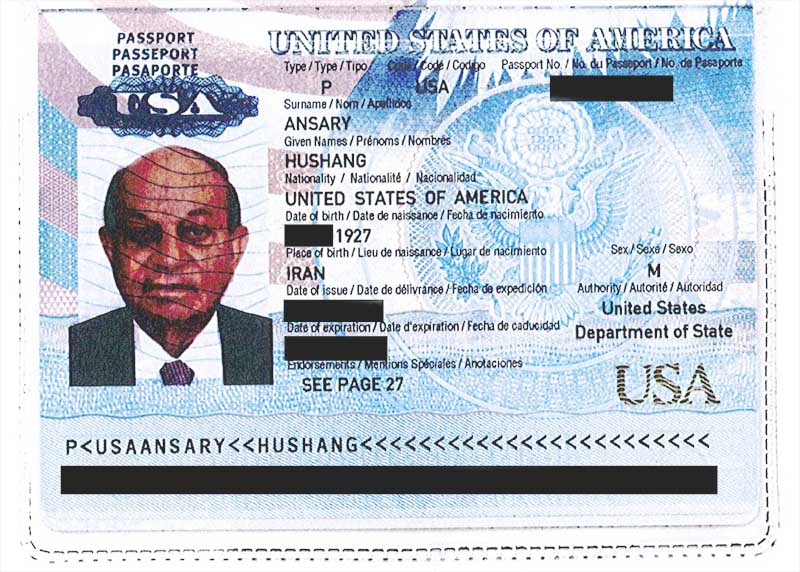

Leaked internal PwC records that ICIJ reviewed present a seeming and central contradiction around Onafield: Ansary was listed in PwC files as Onafield’s owner, even though it was a subsidiary of Ennia — under the control of Curacao’s central bank — which is suing Ansary. PwC’s “know your customer” files on Onafield contained a copy of Ansary’s passport as well as a chart stating that he owned the firm, but in interviews Ansary repeatedly denied any knowledge of Onafield’s incorporation.

The central bank did not directly answer ICIJ’s repeated questions as to whether it, or Ennia under its control, incorporated Onafield. But an official close to the central bank indicated that circumstances around Onafield were under investigation. “Our understanding may be further informed as investigations continue,” the official said. The official said in an email that Onafield had been incorporated for “tax purposes based on a preexisting tax advice from PwC Cyprus.” The official did not provide a clear explanation of what that tax purpose was.

In early 2019, PwC Cyprus helped create another shell company serving as a branch of Onafield and registered in Dallas. Its name was also Onafield Ltd. It remains unclear who directed this firm to be registered. In a meeting held at PwC’s Nicosia, Cyprus, office on Jan. 22, Onafield’s directors authorized plans to transfer a $301.8 million “loan receivable” to the new Texas-based Onafield. Documents show that the move entitled this company to be paid the entire balance of the loan, although it’s unclear how much of the loan, if any of it, was ultimately paid to the newer Onafield. The entity responsible for paying the loan to Texas — at least on paper — was EC Investments, the Ennia investment company.

In an initial interview, Ansary said he hadn’t heard of the large loan receivable. Then in mid-October, he told ICIJ that he had passed the information “to PwC in Houston immediately for explanation,” adding, “I was told that they have asked Cyprus for information.”

A few days later, Ansary told ICIJ that the loan receivable transfer was a “deferred tax benefit,” though he was vague about the details. In a subsequent statement he indicated that this was only a guess at what it could be. Weeks later, Ansary told ICIJ that PwC had given him no answer about the loan receivable transfer to Texas.

Reuven Avi-Yonah, a University of Michigan law professor and international tax expert, told ICIJ that a business in the United States that holds a loan receivable can take tax deductions if the loan goes into default.

Emails from mid- to late-2020 show an official at Ennia communicating with PwC Cyprus employees about paying taxes on a $760,496 profit that Onafield in Cyprus was estimated to make that year. The emails indicate that Ennia employees had at least a degree of control over Onafield in 2020.

The official close to the central bank said that the Cyprus-registered Onafield also made payments to PwC Cyprus and to Centralis, a corporate services firm that helped administer some of Ennia’s shell companies, including the Onafield incorporation in Texas.

Centralis did not respond to repeated requests for comment about Onafield and the loan transfer. PwC also declined to comment on the loan transfer.

Internal PwC documents contain unsigned invoice payment records for the Cyprus-registered Onafield between 2019 and 2022 that list as an intended signatory the name of Abdallah Andraous, a co-defendant of Ansary’s in the central bank’s litigation and one of Ansary’s co-investors in Ennia. In response to ICIJ’s questions, his attorney, Rutsel Martha, said Andraous had nothing to do with Onafield, writing in an email: “Mr Andraous has never heard of this company.”

Bankrupting a company ‘in perfect shape’

In late 2021, Curacao authorities won their initial case against Ansary, with a court on the island ordering Ansary and others to pay $563 million to Ennia. Ansary appealed, asserting that his investments were sound and that funds the central bank was seeking were never part of the insurance business.

In a partial ruling this past September, an appeals court affirmed Ansary’s liability but lowered the sum that he and his co-defendants owe. The appeals court reduced the amount they must pay relating specifically to Ennia’s Stewart & Stevenson dealings from $415 million to $117 million. In addition, the appeals court said Ansary and some of his co-defendants must pay Ennia $11 million for an improper investment in oil rigs and another $14 million for using Ennia money to dispense donations to political figures, pay consultants and “phantom staff” in the U.S.

The appellate judges said Ansary and others are potentially liable to pay tens of millions more in what they call improper uses of Ennia money for private jet travel, consultancy fees, supervisory directors’ fees, dividend distributions and other purposes unrelated to Ennia’s business. But the court delayed calculating those additional damages pending a review by independent experts.

Ansary said that the changing calculation called the entire case against him into question and contended that he never allowed Ennia to pay for his air travel. He told ICIJ that he believes Curacao’s central bank is responsible for “bankrupting a company that was in perfect shape” by mismanaging Ennia and scaring off potential customers through declarations of insolvency.

“You can take any company that is in excellent financial condition … and declare that it is in bad business, declare that it cannot have the confidence of its policyholders,” Ansary said of the central bank’s management of Ennia, “and it doesn’t take more than five years to push it into bankruptcy if that is your intention. And that, we will show, was their intention.”

‘It is everything to us’

Curacao is widely known as a place where tourists flock to beachside villas, but for decades its economy centered on a vast oil refinery in the heart of Willemstad. There, neighborhoods were blanketed by downwind sulfurs and other toxins, raising complaints from residents and environmental groups. The refinery operated for roughly a century, giving Curacao a major income source outside of tourism. In 2018, though, the refinery’s main customer, Venezuelan conglomerate PDVSA, ceased its business on the island and left the country’s huge oil system mostly idle. Unemployment spiked to more than 20%.

Two years later, the COVID-19 pandemic battered the tourism industry, sparking fears of an economic crisis. Although tourism is recovering, there is widespread angst across the island about its economic future. The drop in oil and tourism revenue has been coupled with high inflation that has outpaced Curacao’s Caribbean neighbors. The unaffordability of basic living necessities — food, water, air conditioning — is a constant topic of conversation. In this way, the dependency of the approximately 30,000 residents of Curacao and neighboring islands on their pensions, which provide fixed monthly payments to retired workers of firms that used Ennia as their pension provider, has become all the more crucial.

Signs of Curacao’s hundreds of years as a Dutch colony pervade Willemstad, from its baroque Dutch architecture to a visible show of wealth by the remaining European population. The two- and three-story 17th-century buildings of the city center are either assiduously maintained with bright pastel exteriors or look like ancient ruins, weathered by a constant salty wind known to shorten a structure’s lifespan.

Only a few modern office buildings rise above the low-slung city. The most prominent building on Willemstad’s east side is the Ennia headquarters, the massive glowing letters of its logo a reliable landmark for orienting tourists. Ennia, which is the largest source of health, life and car insurance in Curacao, also looms large over tens of thousands of livelihoods on an island that is wary of meddling from powerful outside forces.

Across the country, most everyone knows the problems with Ennia and its importance to the island. In conversations, the name “Ansary” is invariably enunciated out of the mix of languages: Dutch, Spanish, English and Papiamento, the creole language common on the island.

ICIJ spoke with more than a dozen Ennia pension holders, including teachers, nurses, a mechanic, a hospital janitor and people who worked in the country’s financial sector. Lisette Croes, a 74-year-old Curacao resident, now draws $500 per month from her Ennia pension from when she worked at a bank in Willemstad in the 1990s and early 2000s. “It is a serious thing,” Croes said of the pension worries, since she also uses the money to pay for her electric and water bills as well as school supplies for her daughter. “If it stops, I may go to Holland. Maybe they can help me with social security.”

Croes was sitting in the spartan dining area of a popular Dutch grocery chain. A few feet away, just inside the constantly moving sliding door, a 70-year-old woman sat on a steel folding chair selling rolls of bright purple lottery tickets. She, too, lives partly on an Ennia pension. “I already live as cheaply as I can,” the woman, who asked to remain anonymous, said. “I have to eat.”

“If Ennia goes down, we go down,” said an 80-year-old woman in Willemstad who relies on the pension with her 81-year-old husband. “It is everything to us.”

Over the summer the Netherlands was in talks with Curacao to loan the country $650 million to make Ennia whole. The deal sought to ensure that no one would lose their Ennia pensions. But Curacao is already struggling to pay the Netherlands back for billions of dollars’ worth of COVID-era loans.

On Oct. 5, the Curacao Chronicle reported that Curacao had decided to reject the loan, writing that the central bank appeared to be interested in gradually shutting Ennia down. “Under this approach, policyholders would receive compensation from the government to offset the expected reduction in their pension payouts,” the Chronicle reported. “However, the exact amount of compensation remains shrouded in uncertainty.”

Peter de Groot, who worked as a claims investigator at Ennia for 28 years until he retired in 2014, said he’s worried about his own pension from his former employer. If his pension indeed gets cut, he said, he may immigrate to the Netherlands, which has a more robust social safety net.

Regardless of what happens with his pension, de Groot hopes Curacao will prevail in its actions against Ansary.

“One way or another,” he said, “the money has to come back.”

Contributors: Dick Drayer, Delphine Reuter, Jesús Escudero