After the Copenhagen stalemate

Modest progress expected at climate talks in Cancun

International climate change negotiations resume at a UN meeting in Mexico, but gains are expected to be modest and focused on narrow issues such as forest protection and climate financing for developing countries.

International climate change negotiations resumed today at a UN meeting in Mexico, but gains are expected to be modest and focused on narrow issues such as forest protection and climate financing for developing countries.

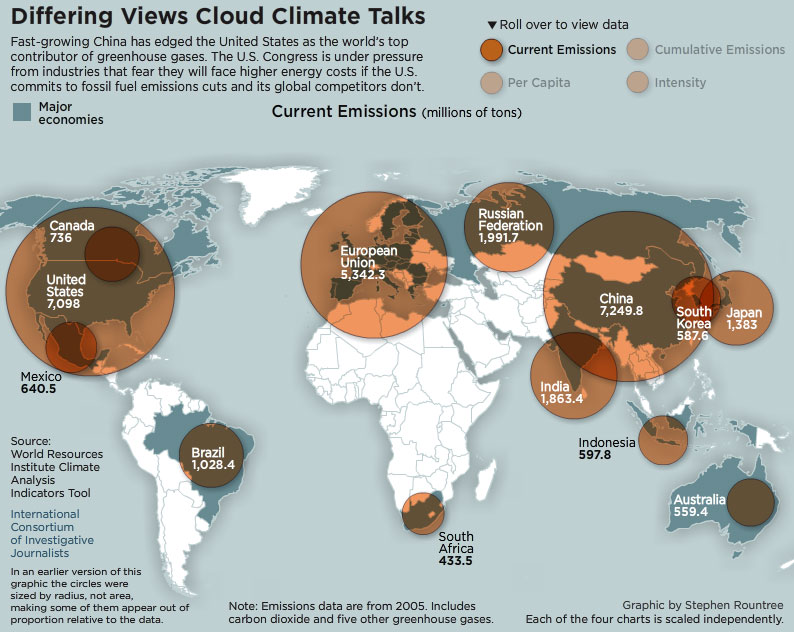

No binding international treaty on emission cuts is yet in sight as many disagreements that led to a stalemate in Copenhagen last year remain on the table. Some differences may have even deepened in the past year due to the economic downturn and strains between the world’s top emitters: the US and China.

Today, U.S. Energy Secretary Steven Chu said the United States risks falling behind China if it does not seize the opportunity to invest in clean-energy technologies. The green technology race with China and other countries is a “Sputnik moment,” he said at a news conference in Washington “We should not, can not, and will not play for second place,” Chu said.

In the meantime, the slow pace of the climate negotiations in Mexico may be just what large carbon emitters in the developed and developing world are counting on.

Last year, an eight-country probe by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists revealed a far-reaching, multinational backlash by fossil fuel industries and other heavy carbon emitters aimed at slowing progress on limits for greenhouse gas emissions. Companies replaced a frontal assault on climate science with a strategy employing thousands of lobbyists, millions of dollars in political contributions, and fear tactics to slow down commitments at the national level, the ICIJ investigation showed. In the weeks leading up to the Copenhagen talks last year, there were 2,810 climate lobbyists in the United States— five lobbyists for every member of Congress.

The lobbying efforts plus the success of Republicans in regaining control of the U.S. House have buried any chance of American climate legislation in the near future. Without a domestic law, analysts say, Washington is even less likely to support an international binding agreement in the event that one surfaces in the next few years.

Looming over all this is the expiration of the Kyoto protocol – the landmark 1997 agreement that set binding targets for industrialized nations to cut greenhouse gas emissions – at the end of 2012.