MEET THE INVESTIGATORS

Behind the scenes of the Panama Papers story that brought down Iceland’s PM

In this special fifth Panama Papers anniversary edition of Meet the Investigators, Iceland’s Jóhannes Kristjansson relives an infamous TV interview and shares insights on telling stories from the heart.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists collaborates with hundreds of members across the world. Each of these journalists is among the best in his or her country and many have won national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

This month to mark the fifth anniversary of the Panama Papers, we speak with Jóhannes Kristjansson, a multi-award winning investigative journalist and documentary filmmaker from Iceland. Jóhannes has been honored for investigations into black market gun trade, sexual abuse of minors, government corruption, and more, and became an ICIJ member in 2016 after his Panama Papers story led to mass protests and the resignation of Iceland’s leader. In this interview, he takes us behind the scenes of his now infamous interview with the Icelandic prime minister, and shares insights and personal stories about reporting from the heart.

Sean McGoey: Welcome back to the Meet the Investigators podcast. My name is Sean McGoey, and I’m an editorial fellow with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

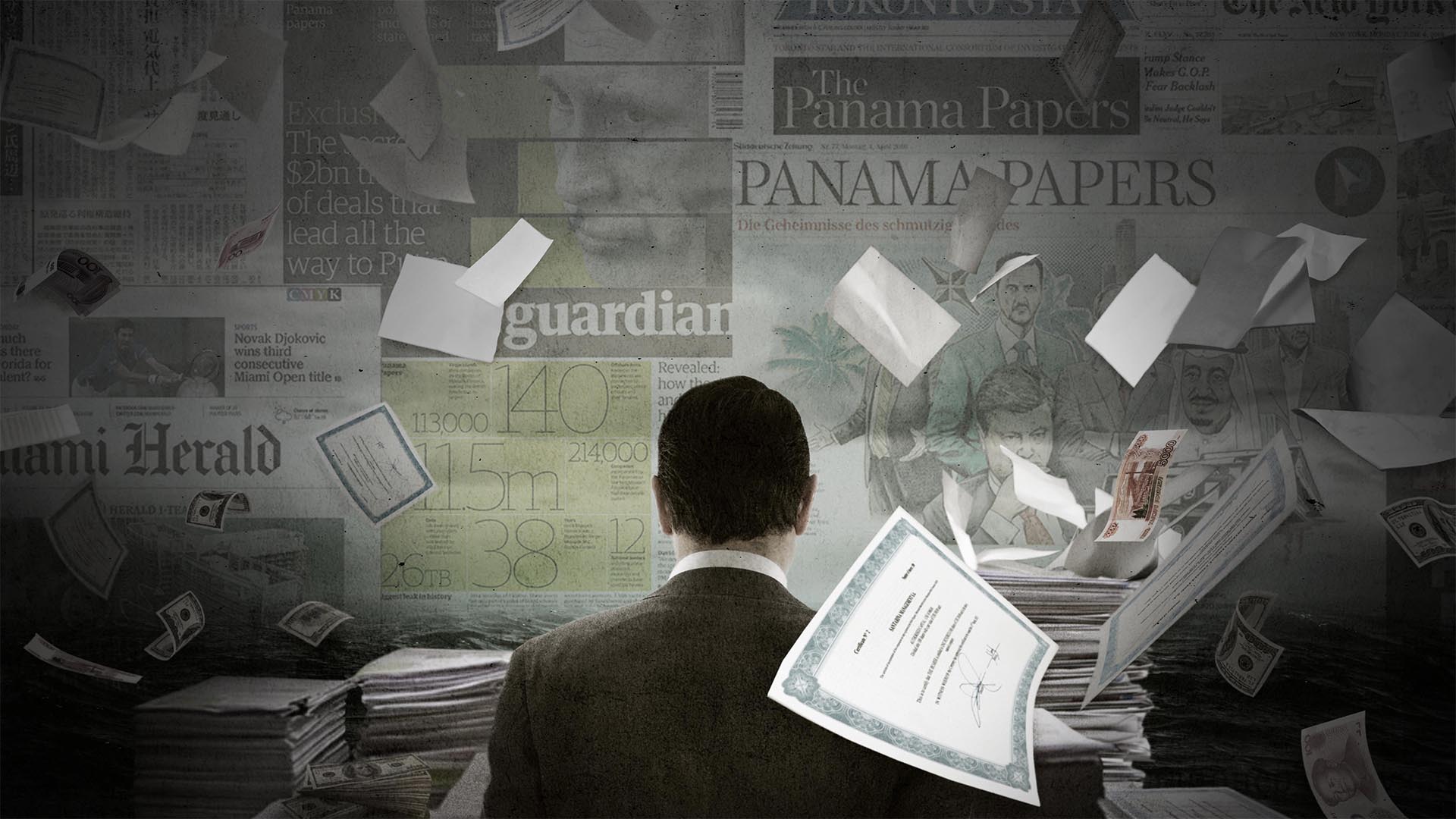

It’s hard to believe that it’s been five years since the world was introduced to the Panama Papers, a stunning collection of more than 2 terabytes of data leaked to reporters at the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung. The source of that leak remains anonymous to this day.

Over 11 million documents shone a light on the inner workings of the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, who facilitated the creation of offshore shell corporations for a list of wealthy clients including star athletes and heads of state.

One of the first major names discovered in the data was that of Iceland’s former prime minister, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson. He failed to disclose his ownership of an offshore company when he became a member of parliament amid the country’s banking crisis.

My guest this month is an Icelandic journalist and ICIJ member who pursued Gunnlaugsson’s story.

Jóhannes Kr. Kristjansson: My name is Jóhannes Kr. Kristjansson. I live in Reykjavik, and right now I am working as a documentary filmmaker.

McGoey: Kristjansson may have set in motion a chain of events that toppled a prime minister, but he says that if he weren’t working as a journalist, he would be doing something completely different.

Kristjansson: I think I would be a farmer in Iceland, in a remote place somewhere, because I partly grew up on a farm. Yeah, I think I would be a farmer.

McGoey: Tell me a bit about what inspired you to want to become an investigative journalist and how you got your start.

Kristjansson: I was constantly asking my father questions about everything. I wanted to know everything and how things work. I’ve been that kind of a guy since I was a child.

I started as a news reporter at Channel 2, a TV station here in Iceland. On the evening news, you do the routine stories about things that are going on in Iceland. But soon I realized that I wanted to do something more. I wanted to dig into stories.

Just a few months after I started, I got permission to do my first investigative story for television. That was about organized crime in Iceland.

McGoey: Your curiosity is a quality that I think a lot of journalists share, but how do you translate that for an audience and get them as interested in your topic as you are?

Kristjansson: When you’re doing a story as an investigative reporter, you try to get all the information out. You try to find the hidden documents or the link between some aspects of the story that has never been told. Especially here in Iceland where 380,000 people live, a big story will be noticed, and everyone is talking about the story, so that is an important factor in everything a journalist should do.

I knew instantly that this was a big story — maybe the biggest I ever worked on. It was a shock, and I was really excited to work on it.

McGoey: Complex stories based on government documents can sometimes be a little dry and hard to follow visually, so working in TV and film, how do you try to make those stories as eye-catching as possible for viewers?

Kristjansson: I always try to have people telling the story, by interviewing people who know something about the story or have some inside info or know something about the documents you are presenting. The attention span for the viewer is better when there’s a person telling you about what’s on the documents.

Sometimes it’s really hard to present a story when you only have the documents and you have to use graphics and voiceover — people can fade out easily. So it can be quite hard to present a complicated story based [only] on documents.

McGoey: The Panama Papers stories all around the world were based on complicated documents, but in Iceland, there was something else that caught the world’s attention — a made-for-TV moment in which the country’s leader stumbled his way through a disastrous interview.

What was it like when you first learned that there was a link to the then-prime minister of Iceland, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, in the Panama Papers?

Kristjansson: I remember where I was, because I was sitting in my car when Marina Walker [ICIJ’s project manager] called me. I parked my car outside a gas station in Reykjavik, and when she told me that the prime minister was involved in the Panama Papers, time froze in my mind. I knew instantly that this was a big story — maybe the biggest I ever worked on.

It was a shock, and I was really excited to work on it, of course. When you have a link to the prime minister in documents like that, you know it’s a big story. Everyone wants a big story.

McGoey: The documents showed Gunlagugsson had an interest in an offshore company named Wintris. But such a revelation is only the beginning. How do you take a piece of explosive information like that and work to turn it into a compelling story?

Kristjansson: In the first months of the work on the Panama Papers, I just tried to get every document related to Wintris and the prime minister. When we were sure that we had found every email and every document, we started to tell the story of the prime minister and what he had been doing in the month before the company was founded and tried to get some background information.

McGoey: After months of reporting, Jóhannes was ready to confront the prime minister, so he paired up with a Swedish colleague, and did an interview that raised more questions than it answered.

Tell me about how you prepared for the big televised interview with the prime minister.

Kristjansson: We always wanted to confront the prime minister with this information. We discussed that for a long time and decided to do the interview like we did because we wanted to get him by surprise.

Then I knew we were doing the right thing, because he was not doing the right thing. He should have answered all the questions.

Iceland is a small country, and if I would have started to call the prime minister’s office or the tax office or any office in Iceland and ask about a company called Wintris, the story would be out in days. So we decided to do it like we did.

It was ideal for TV, but the main purpose was to get his first reaction because as prime minister, he should have declared that he owned this company.

McGoey: That was a clip of you asking the prime minister about Wintris, and him starting to react in a way that ultimately led to him walking out of the interview. What was going through your mind at that point, when you started to be able to tell that you had caught the leader of your country in a lie?

Kristjansson: Me and Sven [Bergman, of Swedish television station SVT], we discussed this. What would happen? We had some scenarios. We had plan A, plan B, plan C. What I was thinking? I was really stressed. My adrenaline was way up. My heart was pumping.

I remember I was sitting there and I was listening to Sven ask some general questions. Then he asked about Wintris, and I wanted to be out of the room. But I knew that I had to stand up and continue to ask questions.

Right after the first question I asked the prime minister and his answer, he just wanted to walk out and didn’t want to answer. Then I knew we were doing the right thing, because he was not doing the right thing. He should have answered all the questions. It was a stressful time.

McGoey: That stress is actually exactly what I want to ask you about. You’ve mentioned that in a small country, word gets around quickly, so in order to conduct an investigation like this, you must have had to maintain an incredible level of secrecy. Can you tell me about the loneliness and isolation that came with working on the Panama Papers?

Kristjansson: That’s a hard question. Working on a story like this in Iceland, where if you go out you always meet someone you know, I knew from the start that I had to be isolated working on this.

I couldn’t talk about the story with almost anyone, so me and my wife, we isolated ourselves. Because my office was at my home. I didn’t have any other office.

My mother-in-law asked my wife, “Why are you living with this man, Jóhannes? Because he’s not working, he’s not doing anything.” Of course they didn’t know I was working on the Panama Papers, and she couldn’t tell them, so my mother- and father-in-law, they really thought I was just a lousy bum or something, not working on anything.

Of course, when the Panama Papers were released, then they understood and were quite happy about it. But it was quite hard.

McGoey: Was there anything that helped you manage your stress during this time?

Kristjansson: I went to a summer house in my family to work there, and I did go out for a walk. That was basically the things I did.

McGoey: One of the results of the investigation was that Sigmundur Gunnlaugsson is now the former prime minister of Iceland, after thousands of Icelanders took to the streets to demand his resignation.

Is there a special responsibility that you feel knowing that your work can help bring about major changes like that?

Kristjansson: That’s the great thing about journalism. The only thing you do as a journalist is gather the information, whatever it is — data or documents or people talking on camera — and then you put the story together and present the information to the public, and the public reacts. That is exactly what journalism is about.

In this case, the general public was mad about the information they received, and they demanded that the prime minister should step down. That is the beauty of journalism.

McGoey: We’re speaking as the fifth anniversary of the first Panama Papers stories approaches. Looking back on the last five years, what do you think the legacy of this investigation has been?

Kristjansson: When people see the story about Iceland and the Panama Papers, of course the prime minister will be the headline. But it was so much more, and this interview is just a tiny part of the work. The main work was in finding the documents, reading the documents, trying to put all the things together.

But of course I am proud of my work and the others on the Icelandic side of the Panama Papers.

McGoey: What was it like working on a project that required truly global collaboration, with reporters and journalists in countries all over the world working on their own Panama Papers stories?

Kristjansson: This cross-border journalism, it’s a really great thing. It’s the future of journalism, I think.

I’m really proud of being a member of ICIJ and knowing all the people, all the journalists around the world who worked with me on this, because we worked together — I helped a lot of journalists, and a lot of journalists helped me.

That is the biggest thing about this project, gathering journalists from all around the world. I really hope that in the future, we will have a lot of projects like the Panama Papers, and in other fields also.

McGoey: And I think this might be my most important Panama Papers question of all. An ice cream shop in Reykjavik came out with a Wintris flavor after your stories were published. Did you have a chance to try it?

Kristjansson: No. I regret that because I really wanted to try it. I should contact them and ask them to do one piece for me!

McGoey: The Panama Papers is far from the only major story Jóhannes has worked on. His current project is a documentary on the response to the coronavirus pandemic in Iceland.

Tell me about this COVID-19 film you’re working on now.

Kristjansson: I got the privilege to get behind-the-scenes access to the people that are at the forefront of fighting the coronavirus here in Iceland. For a year, I’ve been with a camera and my partner, and we have been filming all around Iceland — I think we have been shooting for 270 or 280 days.

On the first meeting I had with the people who are working on this here in Iceland, they told me, “Jóhannes, we know what you have done in your work, and we respect that. You are going to get everything. We are just presenting the truth to the public.” And they have been doing that.

I’ve been filming what’s going on behind the scenes, and that is exactly what they are doing. They are just presenting the facts and the truth to the public, and that is a good thing to know when you are talking about officials working for the government.

McGoey: That must feel like a bit of an unusual approach after your experience with the prime minister. Are there any lessons from the Panama Papers that you carry with you in your work since then?

Kristjansson: When you work on a project like the Panama Papers, you’re working with journalists from all around the world and talking to them and getting information, getting messages, going to all the meetings we had, then you start to think bigger. You know that you can work on stories all around the world.

McGoey: In addition to the worldwide stories you’ve done, you’ve also worked on stories that have had a great deal of personal impact.

Kristjansson: My most personal and most difficult story I worked on was a year after my daughter died. She died from [prescription] drugs here in Iceland — morphine — and she was just 17 years old. As a journalist, working for the state television then, I wanted to dig into this world of young junkies here in Iceland, so I did that.

I went as a journalist with my camera, filming interviews and the daily life of really young people doing drugs here in Iceland, and then I told my daughter’s story on television. I told all of the story. It was really personal, and my hardest story.

It helped me a lot to be able to tell my daughter’s story, and to get to know all the young people doing drugs at the time. It was an eye-opener for Icelanders, because no one believed that children — 15, 16, 17, 18 years old — were doing hardcore drugs like morphine and other medicine or drugs. That was my way to get the information out so that the government could react, and they did in some ways, so it was a good thing.

Of course it was hard for me, but at the end of the day, I feel good, because a lot of people know about my daughter. They know her name, and her memory lives on, so that was also important to me.

Find stories that you work on from your heart, because those stories are the biggest stories.

McGoey: Jóhannes’s series on the underground drug culture in Iceland helped him find meaning in his daughter’s death, but it also touched the lives of many others. He helped get one of his reporting subjects into treatment, and the series set off a national debate that led to Iceland’s health ministry enacting new regulations on the prescription of opioids.

I have one more question: What is a piece of advice that you would give to aspiring journalists?

Kristjansson: My advice to young journalists just starting to work would be: Find stories that come from your heart. Find stories that you work on from your heart, because those stories are the biggest stories.

McGoey: I think that’s a perfect way to conclude our Panama Papers anniversary podcast. Thank you so much for talking with me, Jóhannes!

Kristjansson: Thank you, Sean!

McGoey: Thanks again to Jóhannes Kristjansson for taking time from his busy schedule to talk with us, and thanks to all the journalists who share their stories here on the Meet the Investigators podcast.

We hope you enjoyed this episode. It was produced by Scilla Alecci and me, Sean McGoey.

Send us your feedback at social@icij.org and tell your friends about the show! Please share it on social media and use the hashtag #MeetTheInvestigators to let people know what we’re doing here.

Thanks for listening. See you next time!

—

If you’re a fan of our Meet the Investigators series, please consider making a donation to support ICIJ. Not only will your donation help support our work with journalists like Johannes, but as an ICIJ Insider, you’ll also receive sneak previews, access to exclusive chats with reporters and behind-the-scenes content like this delivered straight to your inbox. Donate today, and support independent investigative journalism.