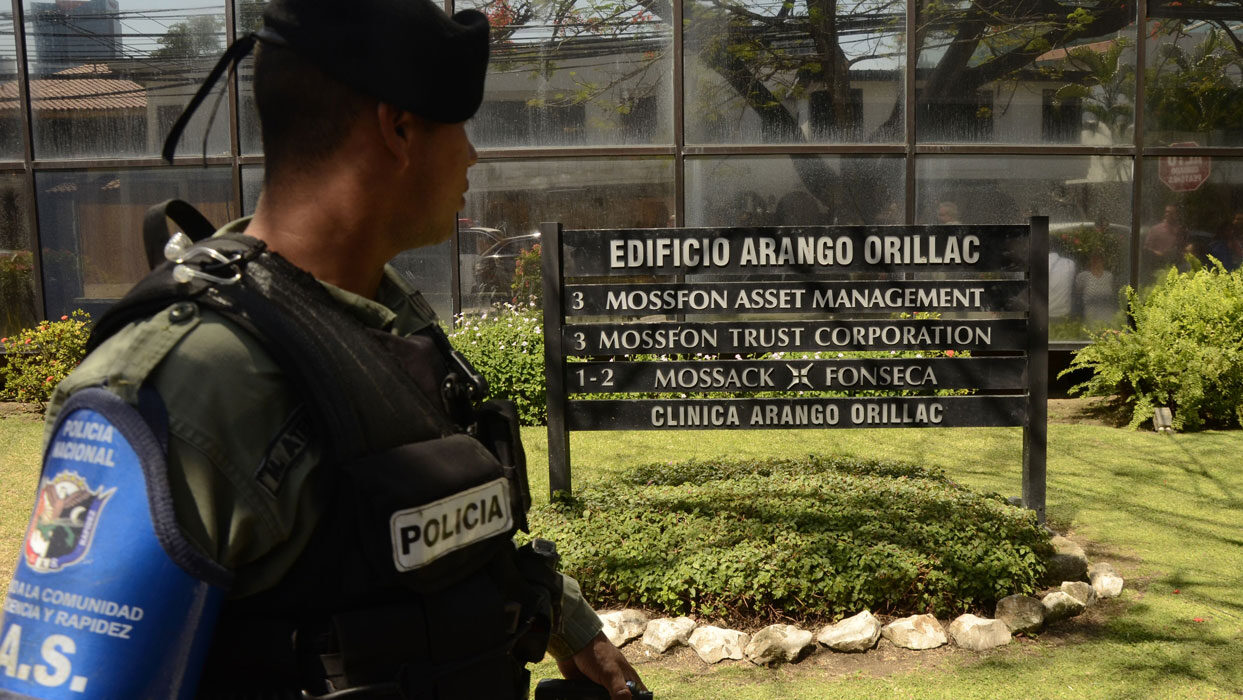

Thirty-two people will be prosecuted for their alleged involvement in money laundering in Panama following revelations made in the explosive Panama Papers investigation.

The trial was announced as transparency activists expressed concern over a separate Panamanian court ruling that they fear could hinder efforts to hold lawyers accountable in cases involving the offshore industry.

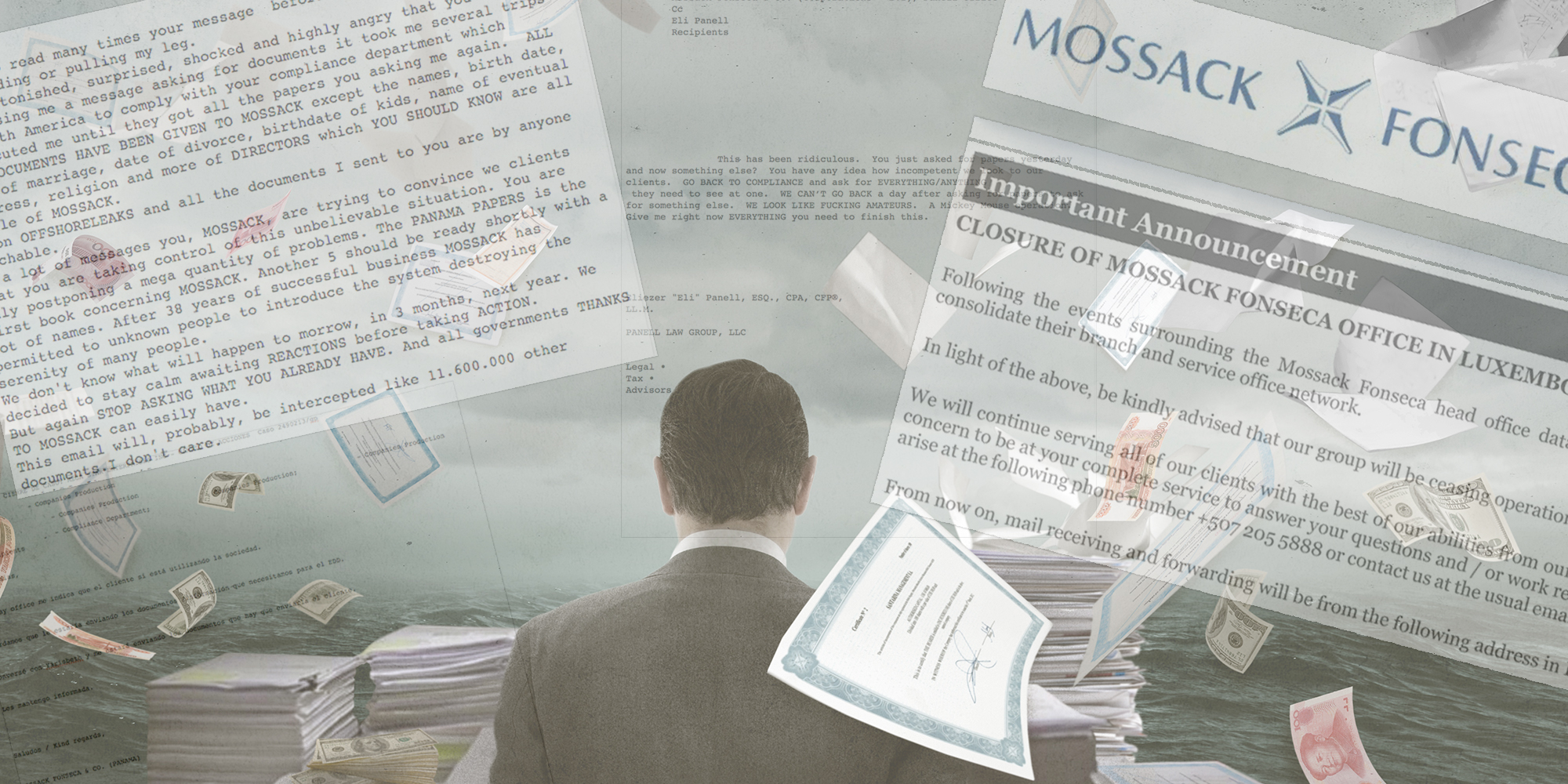

The Panamanian justice department said Tuesday that the trial of the unnamed 32 charged with “crimes against the public economic order” will be held on Nov. 15, 2022. News agencies AFP and EFE reported that Jüergen Mossack and Ramón Fonseca are among the defendants. Both men founded Mossack Fonseca, the influential Panamanian law firm whose 11.5 million leaked internal records formed the basis of the Panama Papers.

Led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the German outlet Süddeutsche Zeitung, the 2016 investigation involving more than 100 media partners around the globe exposed offshore financial secrets linked to world leaders, politicians, criminals and celebrities.

Mossack Fonseca closed two years after the Panama Papers scandal broke. Its founders have insisted that they weren’t involved in illegal activities.

According to Panamanian newspaper La Prensa, prosecutors have investigated whether Mossack Fonseca facilitated the creation of shell companies to move funds that its clients used to pay bribes. Prosecutors claim there is evidence of irregularities. Defense attorneys reject the allegations, La Prensa reported.

Supreme court decision

In a related case, the Panamanian supreme court has exonerated a former Mossack Fonseca employee, Sara Montenegro, who faced money laundering charges linked to the Panama Papers investigation.

Montenegro and other Mossack Fonseca associates were charged with covering up the illicit origin and ownership of money and assets, according to court records.

In the decision, the Supreme Court concluded that services related to the creation of an anonymous corporation, a popular product in the offshore industry, are protected under a Panamanian law created in 1927 and cannot be considered crimes. The 1927 legislation helped transform Panama into an offshore destination for financial secrecy and tax avoidance.

The court also concluded that the creation of corporations or private interests trusts that are used for tax fraud cannot be considered a crime in Panama if the companies were incorporated before 2019. The country changed its laws that year to include fiscal fraud as a crime precedent for money laundering.

“I believe this part of the decision will be hard to understand for the international community,” said Carlos Barsallo, an attorney and former president of the Panamanian chapter of Transparency International. “It will be a challenge for Panama to be part of an international fight against money laundering because nothing that happened before 2019 will count.”

Legal observers noted concerns that the court also ruled that some evidence in the case ought not be considered because it was protected under attorney-client privilege.

One leading Panamanian lawyer, Ramón Arias, said the decision could impact the larger case of the thirty-two defendants facing trial.

“It seems to me that the supreme court in its decision was exaggeratedly simplistic in the analysis of the conduct of the person [Montenegro]. It should have looked deeper into the exercise of the legal profession and the times of the attorney-client privilege,” said Arias, a former president of the Panamanian chapter of Transparency International.

Arias said that while the incorporation of companies is legal, wider ethical expectations need to be taken into account also.

“What needs to be analyzed is the behavior of the legal professional when they create these companies, or in some way find themselves in a situation where they have to help clients in questionable operations,” he said in an interview with ICIJ. “It is in those situations that the attorney then has to exercise discretion and a sense of ethics.”

Panamanian authorities launched the investigation in 2016 following accusations in Brazil that Mossack Fonseca’s local subsidiary had helped create financial structures to hide the proceeds of corruption and tax evasion between 2010 and 2014.

Montenegro was employed as a lawyer by Mossack Fonseca until July 2016, according to court records. After Montenegro moved to a new firm, Mossack Fonseca retained her as outside counsel to represent it in government actions sparked by the Panama Papers, the court records said.

ICIJ was not able to reach Montenegro for comment prior to publication. In an email sent to ICIJ on Tuesday, Feb. 1, Montenegro said that she was not mentioned in the investigation in Brazil and that she did not create companies or provide legal services for the Brazilian citizens involved in that probe.

Two weeks before her May 2019 indictment, Montenegro was elected as substitute deputy for a member of the Panamanian national assembly. As a result, her case had to be transferred to the supreme court under Panamanian law.

The supreme court decision said that emails and voice messages from 2015 to 2017, which prosecutors had intended to rely upon as part of their case against Montenegro, were inadmissible because they were protected by attorney-client privilege.

In an email to ICIJ, Montenegro said that the communications were not related to the alleged crime. (In its ruling, the Supreme Court concluded that the dates of the alleged crimes did not correspond with the dates of the emails and voicemails that the prosecutors intended to use as evidence.)

In a statement sent to ICIJ, the Fundación para el Desarrollo de La Libertad Ciudadana, Panama’s chapter of Transparency International, called the court ruling “unfortunate” and said that it quashes hopes for meaningful systemic change.

“It is clear that the ruling has had both an international and local reputational impact on the perception of widespread impunity, and that the opaque structures that allow the so-called “facilitators” of illicit flows to act are still in force,” the statement said.

This story was updated on Feb. 1, 2022, with comment from Sara Montenegro.