Once again, a major journalism investigation was about to put the small Central American country of Panama in the spotlight.

More than 600 reporters around the world were preparing to reveal findings from the Pandora Papers, a trove of secret financial records obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The massive data leak from more than a dozen offshore service providers scattered around the globe included more than two million records from one of Panama’s most prestigious law firms, Aleman, Cordero, Galindo & Lee (Alcogal), as well as from a Panamanian offshore service provider called Overseas Management Co.

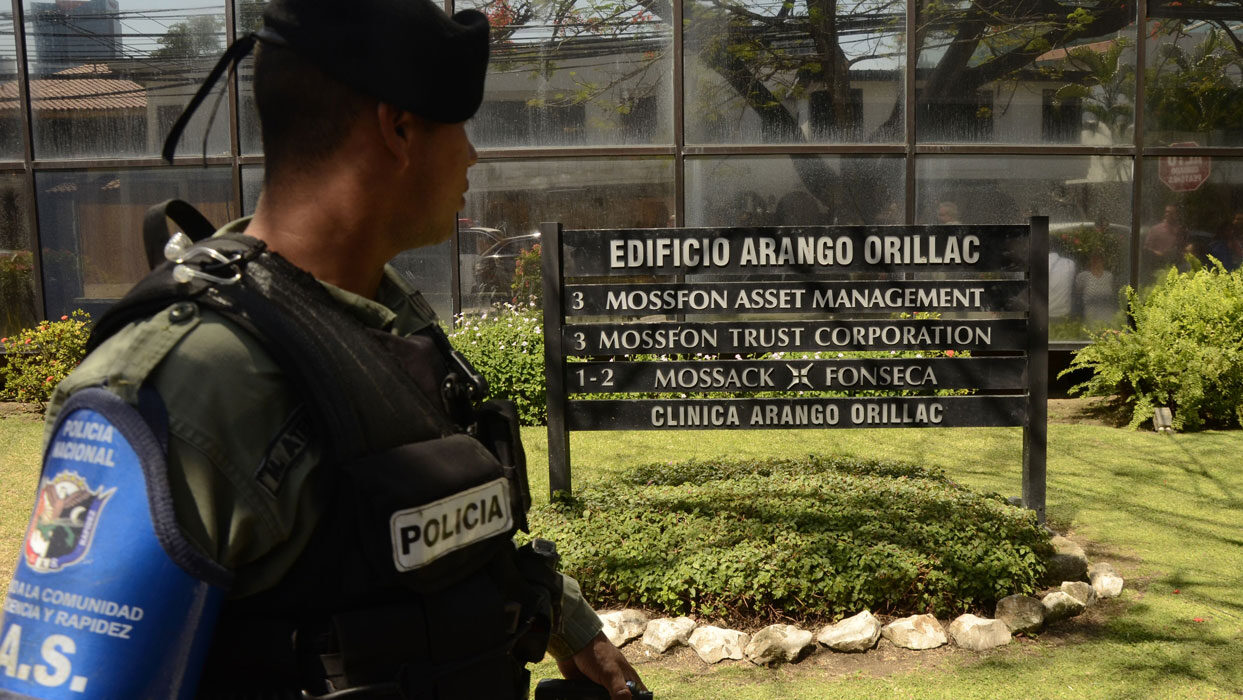

The documents showed the firms had set up shell companies for heads of state, including three Panamanian presidents, along with public officials later accused of corruption. It was the second major ICIJ investigation to reveal Panamanian firms playing a key role in the offshore industry. The Panama Papers in 2016 detailed how Mossack Fonseca had exploited its country’s loose regulations to provide offshore services to the world’s rich and powerful.

Word of the pending investigation sent Panama into crisis mode. After ICIJ asked Alcogal and OMC to comment on our findings, we received an unsolicited letter from a lawyer in the U.S. representing the Panamanian government.

The message: Please don’t tarnish our reputation more than you already have.

“Whatever perception the ICIJ had of Panama in 2016 – in terms of due diligence requirements and supervision of law firms – it is nothing like the Panama of today,” the letter said. “The Panama Government hopes the ICIJ fully understands that it has doubled down on its efforts for a more transparent international tax system in full collaboration with the international community.”

Panama has been classified as a tax haven for decadesand some local offshore service providers leaned on that brand to market their business. In addition to the letter from the government, ICIJ’s outreach to people involved in the story before it published prompted a public commotion, with one former president taking to Twitter to denounce a “reputational attack” against Panama and urge the current president to defend the country.

Reputation matters. Panama doesn’t want to be seen as a haven for corporate secrecy and tax dodging, which can affect a country’s ability to attract international banking and investment. The Panama Papers project, the government said in its letter, had a “significant, negative impact” on the country that was undeserved, given that the focus of the investigation was the actions of a single law firm.

The Pandora Papers came at a time when the country is fighting to get out of the European Union’s tax haven blacklist — controversial, in part, because several European countries are themselves internationally known tax havens — and improve its standing with the Financial Action Task Force, the global watchdog for money laundering and terrorism financing.

In a follow-up letter, Víctor Delgado, the superintendent of a government entity created in 2020 to oversee offshore service providers and a myriad other industries, said the country has made substantial progress to make its corporate system more transparent, prevent money laundering and tax evasion and share information with other jurisdictions.

Experts note that Panama has a long history of enabling corporate secrecy and tax avoidance — a point that Alcogal’s founder acknowledged in a memoir — and that the suggestion that the country itself wasn’t culpable simply isn’t valid. But they agree that Panama has made changes and taken steps in the direction of meaningful reform.

We evaluated some of the reforms Panama says it has taken with the help of experts, including the country’s former tax chief.

Requiring offshore providers to know their clients

ICIJ’s reporting found that Panamanian offshore providers consistently relied on banks and other qualified intermediaries to vet the people behind the companies they set up. As a result, when authorities asked for information on the owners of companies under investigation, the firms scrambled to figure out an answer. This outsourcing of due diligence was allowed under Panamanian law. A 2015 law called on firms to do their own vetting — but without repealing legislation that had allowed for the outsourcing. In November, following the publication of the Pandora Papers, that earlier law was repealed.

Experts say that requiring offshore providers to have the information of real owners of companies is an important step in holding firms accountable and facilitating the investigation of financial crimes.

“This is a basic principle to not dilute due diligence responsibilities,” said Carlos Barsallo, an attorney and president of the Panamanian chapter of Transparency International. “What should follow now is supervision, for the industry to know that they are being constantly and severely audited.”

Creating a beneficial owner registry

In 2019, the Panamanian legislature took what some experts said was a big step toward corporate transparency:It passed a law that sets the framework for a registry of owners and shareholders behind companies and other corporate entities. The owners’ information must be provided by the registered agents — the lawyers who incorporate and act as middlemen between companies and the government. The database will be private and only a limited number of authorized officials will have access to the information, the law says.

With the creation of a registry, the country is making an effort to address international concerns, including from the Financial Action Task Force, about the government’s ability to access and verify information about the real owners of corporate entities.

Financial authorities and transparency advocates consider such registries a useful tool when investigating tax evasion, money laundering, the financing of terrorism and other crimes. Experts say that the creation of the registry is an important step in the fight against financial crimes. But fears of weak enforcement, and limitations on who can access it, may blunt its effectiveness, they say. There’s also been a long delay implementing the legislation.

The law became effective in March of last year and was amended last month. But Panama hasn’t created the registry yet. In his letter to ICIJ, superintendent Delgado said he expected the technological platform that will host the registry will be operational as of next year.

An analysis from Fundación Para el Desarrollo de la Libertad Ciudadana, Panama’s chapter of Transparency International, concluded that the corporate registry law had some loopholes. The group said the regulation doesn’t include effective supervision of those providing the information. Another issue, according to a report from the group, is “the lack of a responsible party to ensure the truthfulness or accuracy of the information provided.”Several articles of the law were amended in legislation approved last month, including to increase the maximum fine for noncompliance from $5,000 to $5 million, and tighten the deadlines to submit or update information.

Delgado explained that, even without a registry, Panamanian authorities can legally request information about the people behind corporate entities from the registered agents, who are obligated to provide it. “Recent experience has shown due compliance when requiring such information by the competent authorities,” he wrote.

“The problem we see is that with all the secrecy surrounding the industry, the systems in place have failed. When those who are supposed to have the information are asked for it, sometimes they simply don’t have it, they can’t provide it,” Barsallo said. “That has been the case for Panama and other countries with a similar system, which is why we have asked for a registry to exist.”

Experts and transparency advocates said that besides centralizing beneficial ownership information, the registries should be open and searchable by everyone, not just certain government entities.

“If the registries were public we wouldn’t need any more leaks, because the information would be available,” said Andres Knobel, a researcher from the Tax Justice Network.

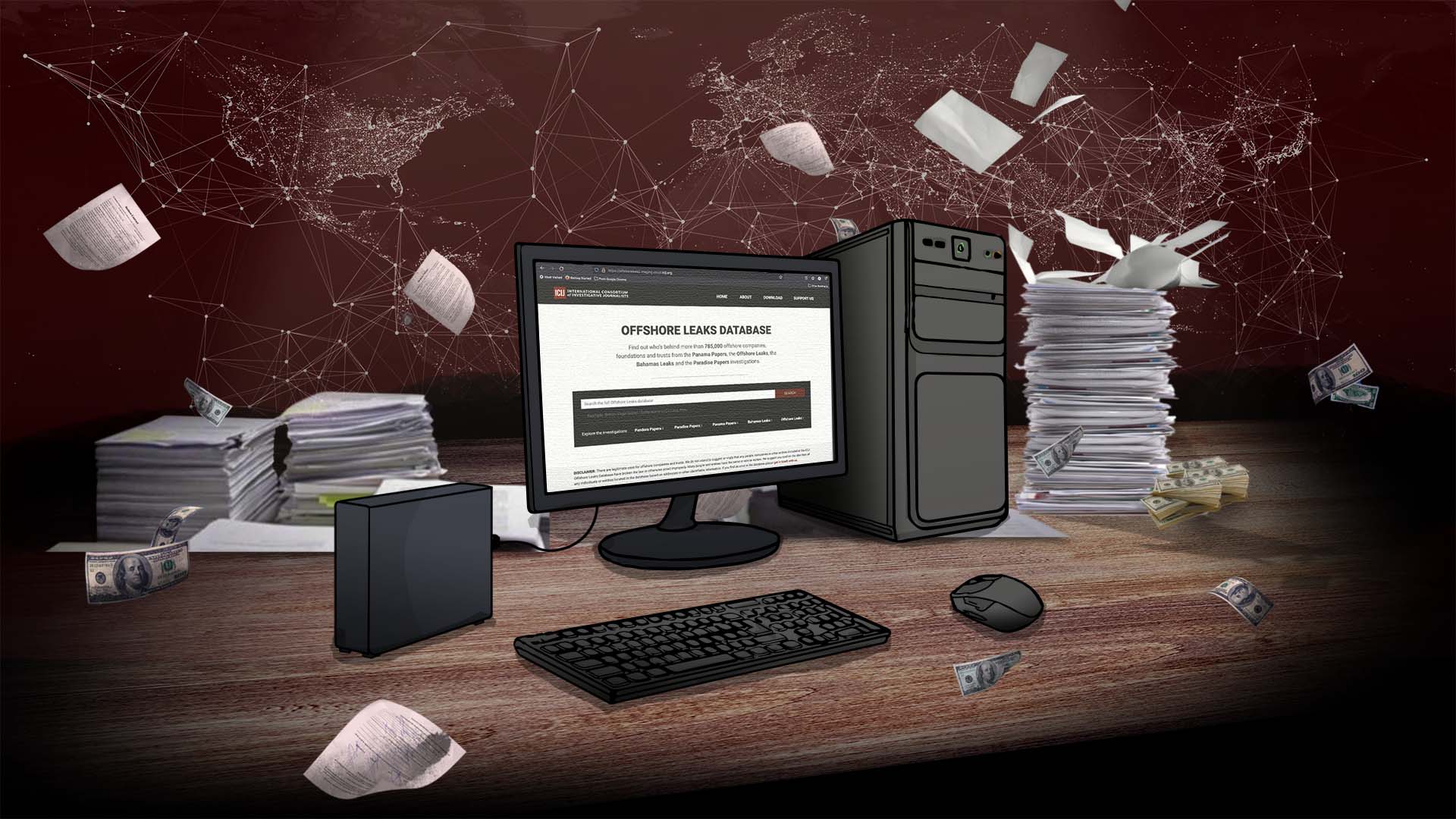

The Panamanian law firm Alcogal is one of two offshore service providers in the Pandora Papers whose records are newly incorporated into ICIJ’s Offshore Leaks Database.

Suspending tens of thousands of delinquent corporations

Panama’s history as a popular destination for company incorporation dates back to 1927 when the country passed the law known as ley de sociedades anonimas. According to some historians, the legislation — which allowed the creation of anonymous corporations that pay minimal to no taxes — responded in part to the interests of Wall Street.The Panamanian offshore services industry born out of that and other laws facilitating financial secrecy and tax dodging flourished in the 1970s. In the following decades, hundreds of thousands of companies, trusts and private interest foundations were incorporated.

In recent years, Panama has suspended more than 385,000 companies — more than half of all those incorporated in the country, government officials told ICIJ.

Officials say that removing so many companies of uncertain purpose from the registry will reduce the overall risk that a company incorporated in Panama will be used to dodge taxes or move illicit money. In most cases, the suspensions appear to have been triggered by the failure of the companies to pay registration fees.

Companies that are suspended lose corporate rights, like their ability to conduct new business or access assets. Owners of suspended companies have to submit a request and pay a fine to reactivate them. If this is not done within two years, the company is dissolved.

“We are certain no other country has taken a step as bold as suspending 50% of all its corporations,” said superintendent Delgado in his letter to ICIJ. “This clearly shows this government’s resolve to ensure transparency and reduce the risk that companies registered in Panama are used for tax evasion or other illicit ends.”

“My rebuttal to that assertion would be: how could we let it get to this point?” said Publio Cortés, who served as Panama’s tax chief from 2014 to 2018, the period during which the Panama Papers was published.

The registry clean up likely started almost six years ago, when Cortés published a list of more than 290,000 corporations that hadn’t paid an annual fee for nearly a decade, depriving the treasury of tens of millions of dollars, and could be dissolved. Cortes said many owners rushed to catch up and avoid suspension, while others simply let the companies dissolve.

“For many years in Panama, there were active companies that did not meet the basic minimum requirements of transparency, many of them did not even have lawyers as registered agents and did not pay the annual fee to the state,” Cortés said. “Neither attorneys nor the country won. On the contrary, there was a high risk that these corporate vehicles were sheltering bank accounts or assets in other countries, without anyone reporting them.”

Experts say paring down the corporate registry is a good start, but that authorities also need to do more to target companies suspected of laundering money or evading taxes.

Increasing international cooperation

For authorities investigating financial crimes like tax evasion and money laundering, being able to request and receive information from other countries is key. Historically, Panama was reluctant to share financial data with authorities in other countries.

The impact of the Panama Papers empowered reformers, leading the country to strengthen its information-sharing agreements.

In October 2016, Panama adopted international information sharing standards set by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Panama has also agreed to exchange tax information with several jurisdictions.

In his letter to ICIJ, Delgado said that since December 2020, Panama “exchanges automatic information of financial accounts” under the OECD’s standards. This enables tax authorities to obtain data on accounts held offshore by residents.

Beyond sharing fiscal information, the Financial Action Task Force recommended in October that Panama take urgent action to show the country is able to “investigate and prosecute money laundering involving foreign tax crimes” and continue “to provide constructive and timely international cooperation for such offences.”

Law changes approved by the Panamanian legislature last month addressed what Cortés, the former tax director, said is an important part of international information sharing: financial authorities will now be able to ask registered agents for the accounting records of corporations.

“In my experience exchanging information with other countries, I learned that this is crucial,” said Cortés. “How can we investigate how much a person owes in taxes if we can’t figure out what assets or how much money their company owns in the first place? How can we help authorities in other countries without those details?”

While Cortés is hopeful the new changes represent steps towards a more transparent system, he said he will remain vigilant.

“It isn’t a matter of approving laws just to approve them, they have to be enforced,” said Cortés, a fervent believer in reforms. “Those in charge of enforcing them need to be supported and given the resources to do their job well.”