A growing number of United States prison systems are dramatically limiting the use of solitary confinement — putting them at odds with U.S. immigrant detention centers, where the overuse and misuse of isolation remains widespread.

A recent investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and its partners found that thousands of the most vulnerable immigrant detainees, including the mentally ill, are being isolated in facilities overseen by the U.S. Homeland Security Department’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for weeks and months at a time.

While tens of thousands of inmates remain locked in solitary confinement for 22 hours a day or longer in U.S. prisons, a reform movement is taking hold — even in some states with notoriously harsh prison systems.

Last year, Texas outlawed the use solitary confinement to discipline detainees in its correctional institutions, restricting it to cases in which a detainee presents a threat due to gang affiliation or other security risks. Mississippi has also sharply curtailed its use of solitary confinement, entirely closing one of its most notorious segregation units.

Other states are weighing reforms. Just last week, lawmakers in New Jersey advanced legislation to reduce the use of isolation cells.

The message for ICE is: Putting people who have not been convicted of a crime in solitary confinement is just wrong.

– Rick Raemisch

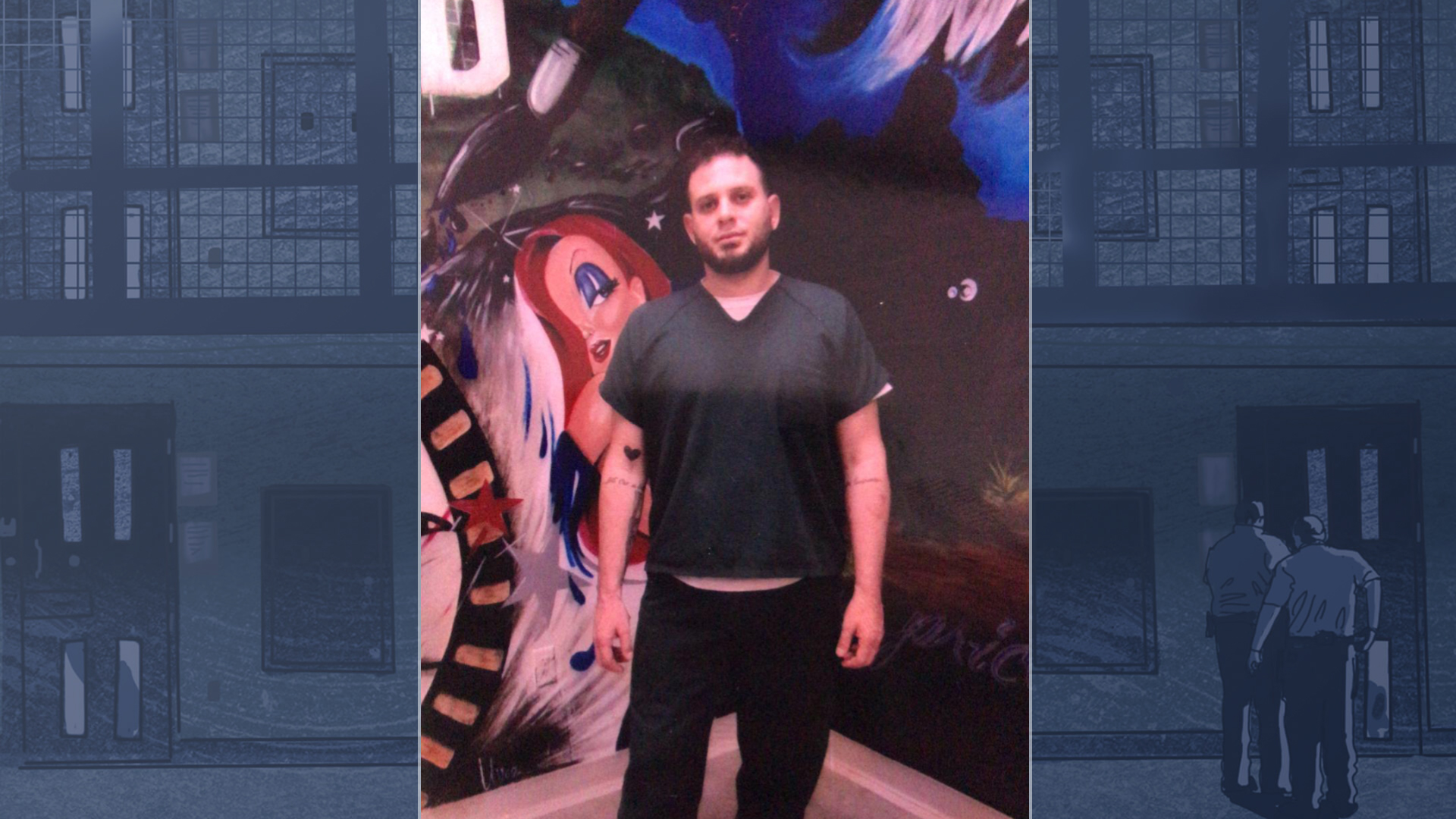

The state that has perhaps taken the most steps to limit solitary confinement use is Colorado. Rick Raemisch, who served as the director of the Colorado Department of Corrections from 2013 to earlier this year, spearheaded the effort.

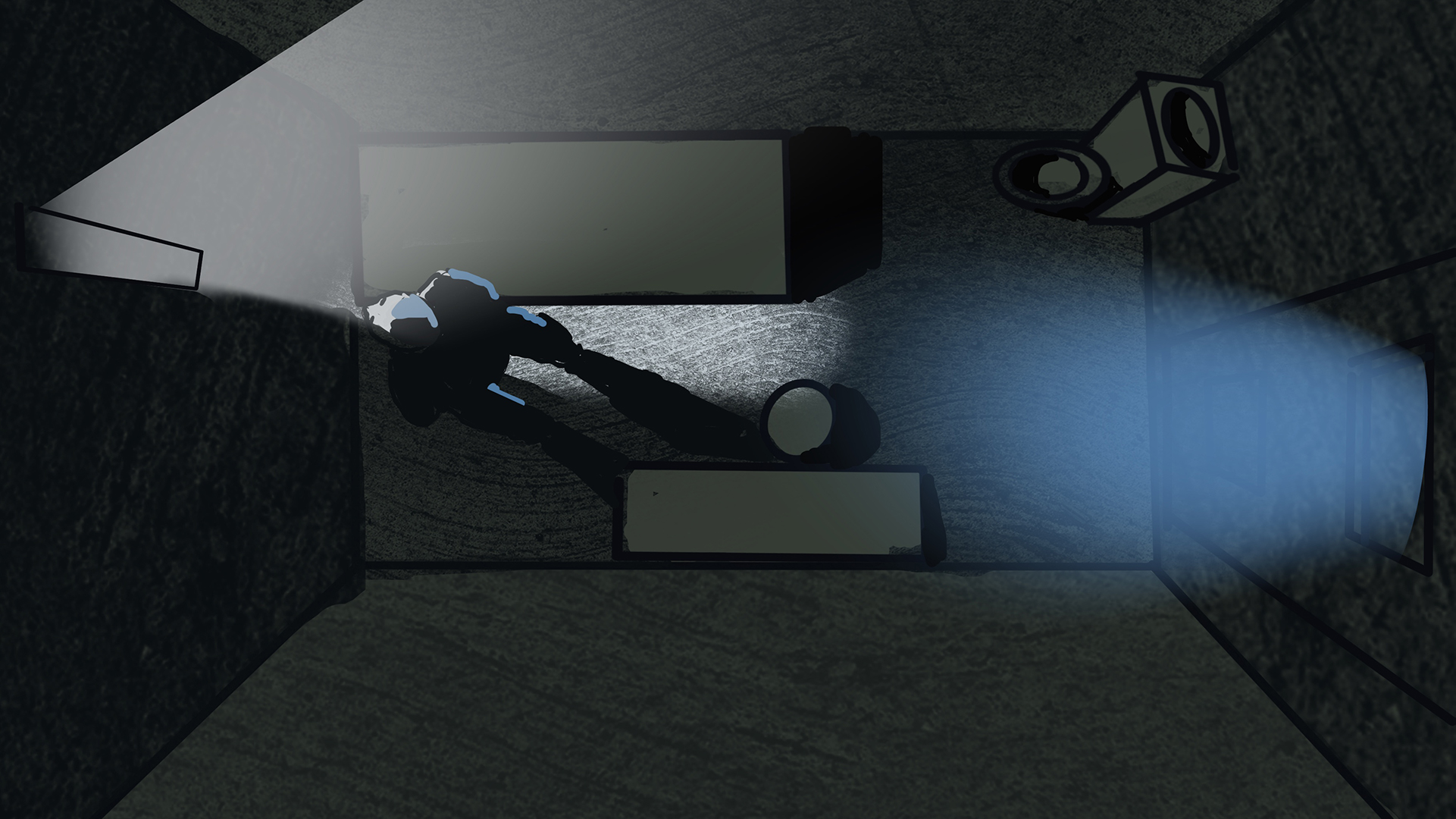

Raemisch, who went so far as to lock himself in one of the state’s solitary confinement cells, spoke with ICIJ’s Spencer Woodman about what his experience, and about what ICE might be able to learn from it.

How did you become interested in changing the way prisons use solitary confinement? Why did you care?

With all my years in the criminal justice system, when you look at locking someone up for long periods of time in a cell the size of a parking space: It’s immoral. It’s unethical. It’s torture. And we’re both multiplying and manufacturing mental illness when we’re doing that. I’m absolutely convinced of that.

What are some examples of reasons why you saw people being placed in solitary in the prison systems you took over in Wisconsin and Colorado?

A good number of those with mental health issues, for example, end up in solitary because they’re so disruptive. Instead of treating the mental illness, you see what I call “the steel-door solution” — you lock a person in a small cell and slam the door. You let the demons chase them around in that small cell 23 hours a day. That’s inherently wrong.

Is solitary confinement a problem with a solution? And can you tell me what you did in Colorado when you took over as corrections director in 2013?

It is. When I got to Colorado, there was a prison dedicated to those who have mental health issues, but solitary was still being used at that facility. So I banned it. A sergeant at one of the facilities emailed my deputy and said: “you’re going to get someone killed.” That sergeant was later asked whether incidents at the facility had decreased after we stopped putting offenders in solitary. He smiled and said: “yeah, by 80%.”

We had turned what were the former solitary cells into what we called “de-escalation rooms” that had soft colors on the walls, murals, waves, wind piping in on speakers, or whatever they wanted. These rooms were open to them 24 hours a day seven days a week — and the doors were unlocked. They had the ability to open the doors and leave. And some individuals were using these five to seven times a day. And that was five to seven times a day that they were not exploding at somebody.

We also banned solitary exceeding 15 days for all of our prisons across the board. [The United Nations said that isolation for more than 15 days constitutes “inhuman and degrading treatment.”]

The results were miraculous. Incidents of violence and self-harm fell.

In addition to creating these “de-escalation” rooms, what were some other alternatives that you instituted to replace solitary confinement?

For those with mental health issues, we began treating them more like patients. We spend a lot more effort treating the mental illness than focusing on the punishment aspect of it. What we emphasized was more of a focus on what caused them to do whatever they did to get them in solitary to begin with and asked: “How can we stop that?” So it was a lot of anger management programs, cognitive programs, programs that teach you to be responsible for your own actions. If there’s a need for punishment, you can take away canteen privileges you can take away phone calls, things of that nature.

And a good number of those who had been in solitary for years were released and never even came back for the 15-day maximum. They behaved.

It’s interesting how we major reforms in solitary confinement practices at state prison systems — which house the majority of US prisoners — and these same types of changes appear to have barely touched ICE detention. Do you have any comment on that?

The data now is so overwhelming on the harmful mental and physical effects of solitary and there is no question that a good number of states are well advanced of the federal system. Period.

The message for ICE is: Putting people who have not been convicted of a crime in solitary confinement is just wrong. I think that they need to understand that there are other alternatives that can be used. This is a practice that needs to stop.