ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia — Hotels along the Djibouti corridor, Ethiopia’s main trade route to the Red Sea, are lately undertaking an unexpected and disturbing role as hospices for commercial sex workers infected with HIV/AIDS.

“There were three girls working with me, and the three tested positive,” said Selam Aregaya, a 21-year-old who dropped out of school after her parents died and now is a commercial sex worker in a hotel in Nazrēt, one of the busiest towns along the Djibouti corridor, 55 miles from the capital city of Addis Ababa.

“The hotel owners help the girls that are sick and let them stay there and even allow them to die there,” she said on a May morning, her head covered with a bright yellow scarf. Occasionally, Aregaya said, the sex workers have been able to pool money to send some of their HIV-infected friends to die at home.

There’s no systematic collection of HIV data among sex workers in Ethiopia, but the latest government survey, in 1998, found that about 70 percent of Addis Ababa sex workers were HIV-positive. A 2006 report by the Ethiopian government identified sex workers as one of the groups with “high or increasing rates of HIV.” Others include refugees, mobile populations and youth.

In a country crippled by poverty and famine, rural girls and women migrate to cities in search of jobs. Unable to find steady work, many wind up engaging in sex work along the country’s main transportation corridors. Even those who get a waitress job or make it to high school often have sex in exchange for money or gifts to supplement their income. They don’t identify themselves as sex workers, and they don’t insist on condom use with their clients, groups working with sex workers in Ethiopia say.

Save the Children, a U.S. nongovernmental organization (NGO), reaches out to women like Aregaya and members of other at-risk groups in the Djibouti corridor with HIV prevention information, counseling and testing, and condoms. The program, called High Risk Corridor Initiative (HRCI), also cares for people infected with HIV.

But former and current program officials said their efforts have been hampered by U.S. policies that emphasize abstinence and faithfulness messages and restrict how they can use funding they receive from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

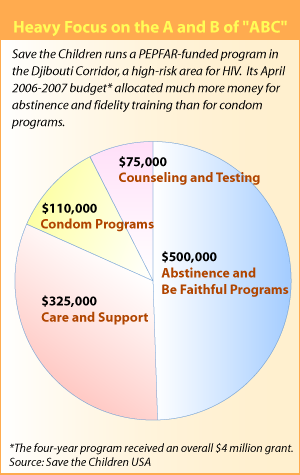

More than 80 percent of HRCI’s prevention budget is allocated by PEPFAR for abstinence and fidelity activities, thus limiting Save the Children’s ability to fully address the needs of sex workers, truck drivers and other at-risk populations they serve.

PEPFAR is a five-year, $15 billion initiative to fight AIDS in more than 120 countries. The majority of the money is spent in 15 “focus countries,” the bulk of which are in Africa. President Bush announced the program in his 2003 State of the Union address, and the first prevention, care and treatment grants were distributed the following year.

The largest commitment ever of U.S. taxpayers’ dollars to fight a disease abroad, PEPFAR applies the so-called ABC approach to HIV prevention: Abstinence, Be Faithful, and correct and consistent Condom use.

This approach was engineered in Africa in the 1980s and has been credited with reducing HIV rates in countries like Uganda. But PEPFAR critics say that the U.S. government has placed more weight on the first two components of the ABC approach at the expense of condom education, thereby leaving at risk those who don’t, or can’t, abstain from having sex.

The U.S. government counters that social marketing of condoms by UNAIDS, the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, and the United Nations Population Fund, among other groups, has not been effective because there are more new HIV infections and condom use continues to be low. According to PEPFAR guidelines, condoms are to be promoted only among high-risk groups such as sex workers, truck drivers, couples in which one of the two members is HIV-infected and youth older than 14 who are sexually active.

In an unprecedented earmark, Congress mandated that starting in 2006 one-third of PEPFAR’s prevention funds be spent on programs promoting abstinence until marriage and fidelity, leaving all other prevention programs to divide the rest of the money. Other programs include condom promotion, safe medical injections, prevention of HIV transmission from pregnant women to their babies, and blood safety.

The 2006-2007 allocation of funding for the HRCI program in Ethiopia reflects the U.S. government priorities in HIV prevention. Even though the Djibouti corridor is considered a high-risk area for HIV transmission, with a steady sex industry and abundant truck transit, the U.S. government allocated $500,000 of the program’s annual prevention budget for abstinence and fidelity activities, including prevention classes in 28 area schools. In 2006, only $110,000 was allocated for condom programs for commercial sex workers and other high-risk groups such as truck drivers.

Nolawi Abiy, Save the Children’s HRCI prevention programs coordinator, accompanied ICIJ in a May visit to the Djibouti corridor program, which includes 21 HIV information sites along the route’s 570 miles. “A lot of the money is allocated already for ‘AB,’ ” Abiy said, referring to the “Abstinence” and “Be Faithful” components of the ABC approach. “Even if we want to do something else, we cannot.

“It’s really hard to talk to PEPFAR about these things,” he added.

-

The four women on the right say they engage in commercial sex work in hotels - The former Djibouti corridor program manager, Beverly Stauffer, can attest to that. Promoting HIV prevention in a high-risk area with a big portion of the budget earmarked for abstinence programs, she said, was “tough.” She tried “pretty drastically” to persuade PEPFAR to increase the money going to other forms of prevention, which include condom promotion, as well as to care programs aimed at people infected with HIV, but her efforts were unsuccessful.

“[I] was informed that funding would not be increased for either of these areas of need,” she said. Specifically, Stauffer was hoping that the funding would enable clinics to reach commercial sex workers and other vulnerable women with care for sexually transmitted diseases, specialized voluntary counseling and testing, and family planning services.

The U.S. State Department’s Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator, which runs PEPFAR, did not respond to numerous calls seeking comment on the HRCI program.

Stauffer left the Djibouti corridor program in March 2006 after nine months on the job. A former public health officer in Kansas who had worked on HIV programs in Egypt, Jordan and India, she remained in Ethiopia doing consultancy work.

Stauffer said she complied with PEPFAR rules and earmarked funding while also using her creativity to get out other prevention information she thought important. Her abstinence programs in school areas took the form of a “life skills” curriculum that taught young people about relationships, how to deal with peer pressure and the basics of HIV transmission. She also set up out-of-school groups where those same students could get information about condoms. “I was trying to stay fairly pure to my funding,” she said. “At the same time, you have to have integrity and you have to say that’s not enough programming for youth, you have to find ways to reach those youth who need family planning or condoms or whatever.”

The HRCI program predates PEPFAR. It was launched in 2001 by Save the Children and the International Organization for Migration, with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development. It was Save the Children’s first grant for HIV work in Ethiopia.

PEPFAR took over the funding of the program in 2005. A series of conditions and rules was attached to the new four-year, $4 million grant.

The new rules, Abiy said, required the program to include abstinence and fidelity in all of its HIV prevention messages, including those aimed at sex workers. “When we give a ‘C’ message [referring to the “Condom” component of the ABC approach], they [PEPFAR] want us to include that ‘AB’ [“Abstinence/Be Faithful”] is the only 100 percent effective method,” explained Abiy, who said he was not talking on behalf of Save the Children. “We told them that that is not a feasible situation. It’s against their business. You can’t expect a commercial sex worker to be faithful.”

In response to written questions, Eileen Burke, a Save the Children’s spokeswoman, said the organization does not teach commercial sex workers about abstinence and fidelity.

Another PEPFAR requirement is that participating programs emphasize condoms’ failure rates, a provision Abiy said can be dangerous in a country like Ethiopia, where misconceptions about condoms abound. According to UNAIDS latest statistics, only 15 percent of women and 36 percent of men ages 15-24 in Ethiopia reported using a condom the last time they had sex with a casual partner.

The Djibouti corridor program is an example of the frustrating situations PEPFAR rules can create in the field. While Bush’s initiative is credited with giving thousands of HIV patients access to treatment, it is criticized by AIDS activists and the Government Accountability Office for imposing rigid rules that might end up hurting prevention efforts.

A 2006 GAO investigation concluded that the abstinence earmark challenges country teams’ ability to respond to local needs, epidemiology and cultural patterns. The U.S. government granted exemptions to the abstinence spending requirement to eight of the 15 countries after the countries’ PEPFAR teams said, among other things, it would affect their ability to fund prevention programs for high-risk groups and pregnant women. Ethiopia, like other countries with larger PEPFAR budgets, was not on the list of those eligible to apply for a waiver.

Local and foreign NGOs in Ethiopia worry that PEPFAR’s heavy funding of abstinence-only programs deepens misconceptions about the disease and denies young people critical information to protect themselves. Even American faith-based groups working in Ethiopia and other African countries have started to debate whether to include a session on condoms in their PEPFAR-funded abstinence programs. They say data from the field are showing that young people have many “barriers” to abstinence and faithfulness.

“Human beings are complex, holistic,” Tatiana Shoumilina, UNAIDS monitor and evaluation adviser, said in an interview at the United Nations compound in Addis Ababa. “Abstinence and fidelity work as long as you are also saying use condoms, diminish the number of partners, eliminate the most risky practices.” In her opinion, if people are presented with all the prevention options, they can choose the one that may best help them in their situation.

Abiy lamented the lack of a more flexible approach, especially in the programs that target young people along the Djibouti corridor. “We need a broader perspective; we need to tell them about condoms, about sexuality,” he said.

Rules vs. reality

-

This information center is one the 21 HIV/AIDS sites set up by Save the Children along the Djibouti Corridor

The first cases of HIV infections in Ethiopia were reported in the mid-1980s — a time when condoms were a social taboo, advertising of family planning was illegal and some government officials didn’t hesitate to call HIV “a disease of prostitutes” or bluntly deny its existence.

Despite those hurdles, Mengistu Haile Mariam, the longtime dictator who overthrew the last Ethiopian king, established the first HIV/AIDS program in Ethiopia — one of the first in Africa — in 1985. Among other measures, he allowed the distribution of about 2 million condoms among public servants.

Political unrest and other government priorities such as reducing poverty significantly weakened the HIV efforts in the ’90s, when the epidemic spread into the general population. It wasn’t until 1998 that Ethiopia came up with a comprehensive national HIV policy.

Today, in this country of 77 million people, about 1.3 million are living with HIV — one of the largest groups of infected people in the world. Infection rates have stabilized in some urban areas in the past few years and are starting to level off in the countryside, where 85 percent of the population lives, UNAIDS and Ethiopian government figures show.

Despite support among Ethiopians for abstinence-until-marriage messages — which are taught by the two main religions, Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and Islam — many young people engage in premarital sex. A 2002 survey showed that 49 percent of high school dropouts and 16 percent of high school students had had sex. The figures may be low by U.S. standards, but they stand out in the context of a conservative country like Ethiopia.

HIV rate in the 15- to 24-year-old group is the highest in the country. At 8.6 percent, it is more than double the national rate. In a country that ranks 134th in the world in gender-related development, according to the United Nations Human Development Report, it’s no surprise that women’s HIV rate is higher than men’s.

PEPFAR rolled out here in 2004 and in January 2005 started the first-ever free antiretroviral treatment in the country. It also awarded handsome HIV prevention grants to the powerful Orthodox Church and the Muslim community, the two groups that by far can reach the largest number of people in the remotest places through their networks of churches and mosques.

Muslim and Orthodox officials said in interviews that teaching about condoms leads to adultery or “illegal sex.” They said they don’t talk against condoms in their HIV prevention work, but they don’t address them either.

In documents obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests, PEPFAR officials described as “a major success” of 2005 “the scaling up of the work of faith-based organizations in ‘AB’ [‘Abstinence’ and ‘Be Faithful’] programming representing all the major faiths in Ethiopia (Orthodox, Muslim, Catholic and Evangelical).”

U.S. Agency for International Development officials, who are part of the local PEPFAR team, said that different organizations choose to focus on different parts of the prevention work and that the PEPFAR program has to ensure that each organization feels comfortable delivering its message. “Now, we do everything we can to make sure that the comprehensive [ABC] message gets to as many places as possible,” Bill Hammink, the USAID director in Ethiopia, said in an interview at the U.S. Embassy in Addis Ababa.

PEPFAR’s plan for 2006 in Ethiopia was to reach 13 million people with abstinence and fidelity messages and 3.7 million youth with abstinence-only messages; an additional 8.3 million people were planned to be taught about condoms alongside “Abstinence” and “Be Faithful” messages, government records show.

An analysis of PEPFAR’s budget in Ethiopia shows that while the budget for both AB and C programs increased from 2005 to 2006, abstinence and fidelity funding went up 63 percent while condom funding grew 28 percent.

Evangelicals add condom teaching

From Addis Ababa, the capital, it takes a plane trip and a four-hour drive on a bumpy, dirt road to get to Simada, a rural district in the northeastern Amhara region. The area features a reality all too common for this country: no electric power, no potable water and no medical attention except for a stark health center. According to national 2003 estimates, Amhara has by far Ethiopia’s highest rural HIV infection rate (4.9 percent).

Abebe Awolu, a young nurse who works at Simada’s health center, can relate to this. He told stories of young men, many of them soldiers, who too often walk out of his office with an HIV-positive test result, and of those who arrive there already afflicted by diarrhea, herpes and weight loss. “Deep inside them, they know what they have, but they say it’s TB,” he said. He also knows that young women trade sex favors for food or money at the local beer stores. Those women rarely get tested, he said. “Until recently, there was almost a total lack of awareness” of HIV.

An American evangelical group, Food for the Hungry, does relief work in the area through a contract with the U.S. government.

On a recent afternoon, hundreds of people waited outside the Food for the Hungry compound to get their USAID sacks of wheat as well as their rations of cooking oil. Some had walked barefoot for days. Grandmothers were carrying on their backs their listless grandchildren, whose parents, the women said, had gotten sick and died of an unknown disease.

Many children and women wore Orthodox crosses around their necks, and a few men had Kalashnikov rifles tied to their backs — memorabilia from wars their ancestors fought and now a symbol of status among the poor. Almost everyone nodded when asked whether HIV/AIDS was spreading in their communities. The real urgency for them, though, was the wheat because they hadn’t eaten in days.

But while some Food for the Hungry employees organized the food delivery, there was more going on inside the humble compound of the Phoenix-based relief and development organization.

Half a dozen adolescents wearing white USAID-sponsored T-shirts that read in Amharic “through chastity and fidelity let’s save lives” hurried to learn a lesson they would have to teach other youth the next day. It would be the first of 12 classes of a PEPFAR-funded HIV program aimed at delaying the first sexual encounter among young people and teaching faithfulness in marriage — the first structured HIV intervention in this corner of the world.

That day, the class would include teachings about self-respect and self-confidence, and also the fictional story of a girl called Alamitu, who lost her virginity, contracted HIV and died.

The youth, chosen to be peer educators, were coached by Hika Alemu, a soft-spoken Ethiopian who says metakeb, abstinence in Amharic, is supported in Ethiopia “by the very culture, the sentiment.” He believes they will make a difference in Simada. “The only problem is the lack of money and the starvation,” he added.

With the belief that HIV/AIDS “is waiting for a Biblical solution,” Food for the Hungry expects to reach almost 170,000 young people in three districts of the Amhara region, including Simada, in the next three years. The program also covers other regions of Ethiopia.

The money comes from an $8.3 million PEPFAR grant to teach HIV prevention in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Mozambique and Haiti alongside other evangelical groups Food for the Hungry partners with. The funding is part of PEPFAR’s HIV/AIDS Prevention through Abstinence and Healthy Choices for Youth program, a $100 million pool of abstinence grants managed directly out of USAID headquarters in Washington, D.C. Nine of its 14 grantees are American faith-based groups.

In the past few years, Food for the Hungry has been involved in smaller HIV programs in Africa, some of them side efforts to the food and development programs that constitute the organization’s core work. To date, the PEPFAR grant is by far its biggest commitment in HIV prevention.

In Simada, Food for the Hungry’s prevention program, which includes a pledge of abstinence in the last session, has many locals excited. “We are very happy with it on behalf of the state,” said Abebe Chane, a young official with the regional government youth programs. When asked whether youth in the community were sexually active, he laughed. “Definitely! For sure,” Chane said. He added that condoms were available in the area but that many young people “are too shy” to acquire them. “If they were practicing safe sex, the HIV rate wouldn’t be this high.”

Chane hopes that through Food for the Hungry’s program, young people in Simada will be persuaded to change their sexual behavior.

Alemu agrees. He said youth can be convinced to practice “secondary abstinence,” a commitment to stop having sex that many PEPFAR partner organizations are promoting these days. “People are dying. Their friends are dying. So they want to abstain again,” Alemu said.

Condoms are not part of the HIV prevention curriculum called Choose Life, which features stories from the Bible and was borrowed by Food for the Hungry from World Relief, a faith-based group in Baltimore. When questions about condoms arise in the training Food for the Hungry officials answer them if those asking are older than 14.

Asked about the rationale behind suppressing condom information from older youth, unless they specifically ask for it, Andy Barnes, director of all Food for the Hungry programs in Ethiopia, said the group is filling “a niche that’s being ignored.” He added: “Condom teaching has been done. We are filling a gap.”

However, unlike other areas of the country, especially those close to urban centers, residents of Simada have no access to structured HIV prevention programs or media messages that teach about condoms. This is true for most rural areas in Ethiopia. A 2002 HIV/AIDS survey showed that farmers throughout the country said they didn’t use condoms because, among other reasons, they lacked basic knowledge about them.

That could start to change soon. At Food for the Hungry’s headquarters in the United States, researchers are pushing to expand the Choose Life curriculum to accommodate situations encountered in the field. In the works are chapters on condoms, sexual abuse and gender equality.

Tom Davis, director of Food for the Hungry health programs, said youth have many barriers to abstinence, including peer pressure and lack of the necessary skills to delay sexual initiation, and that his organization is working to figure out how to make abstinence and fidelity a reachable goal for them. Davis said some youth could be experimenting with oral and anal sex while they believe that they are abstinent and protected from HIV. He is conducting surveys in Ethiopia and other countries to learn more about sexual behavior among young people.

Davis said that a condom chapter will not be implemented without controversy among some of his faith-based colleagues in the field. World Relief and other faith-based groups, he said, know that it would be difficult to persuade the churches they partner with in Africa to teach about condoms. “It’s not a moral objection that I see in a lot of places; it’s more, how could we do this? Even if we wanted to, how can we get churches to talk about this?”

Davis, a United Methodist from North Carolina who says that “faith and science can coexist and do coexist,” said he hopes that data coming from the field will help his efforts to broaden Food for the Hungry’s prevention work in Ethiopia and other countries. “If we can show that 30 percent of youth are having oral sex, well, that will be a very good place to start with churches and say, ‘Look, this is what’s happening. We need to talk about it.’ ”

For now the new condoms chapter of the Choose Life curriculum will only be taught to those youth that choose not to take the abstinence pledge at the end of the training.

Meanwhile, other PEPFAR partners in Ethiopia are finding their own ways to deliver a message that includes all prevention options. Family Health International, a U.S.-based nonprofit public health organization, has received PEPFAR funding to run abstinence and fidelity programs, but it managed to supplement its “AB” funding with money it got from Impact, a USAID program that predated PEPFAR and allowed a more flexible approach.

Francesca Stuer, Family Health International country director, said all of its programs in Ethiopia are “fully comprehensive” and tailored to the needs of the specific groups they assist. A native of Belgium, she said that by mingling funds, Family Health International officials feel “more free and less stressed about helping our target groups address the realities they face in their day-to-day life.”

One example is Family Health International’s HIV prevention program for taxi drivers in Addis Ababa.

An estimated 28,000 taxi drivers, inspectors and assistants interact with as many as 1 million Addis Ababa residents every day. A majority are men, and many are young and single. They usually have cash at their disposal — almost a rarity in this country. Several studies have concluded that they are at high risk of contracting HIV.

On a May morning, about a dozen taxi drivers had gathered in a small shop in the Kalfe Efoita Market, a busy commercial area in the heart of Addis. They were chewing khat, a popular leafy stimulant, and having an animated discussion about HIV. The lesson of the day, taught by two of their fellow taxi drivers, was on the correct use of condoms.

“We shouldn’t be shy of having condoms in our pockets,” Assegid Mandefro, a 32-year-old peer educator said while producing a condom and showing how to check the expiration date on the cover. “We should not be shy buying condoms, holding them in our hands or using them.” To the attentive eyes of his colleagues, Mandefro blew into the condom to show its capacity and strength.

There were laughs and some jokes in Amharic, and the training continued for about 20 minutes, touching on sexually transmitted diseases, the price of condoms and other practical advice. The meeting finished with a characteristic double clap of hands by all the participants.

“Before these discussions, we didn’t use condoms all the time,” Ashenafi Mekonnen, a 24-year-old taxi assistant with curly hair and lively black eyes, said after the training. “Now we use condoms consistently. This is what we are taught to do.” He added that they have also learned about abstinence and fidelity, and some of his friends have chosen to follow those principles.

U.S. government funding for the taxi drivers program ended in June of this year, but the Dutch government has picked up part of the tab for the program to continue. At the same time, Family Health International is bidding for more PEPFAR money to continue the training.

As PEPFAR enters its fourth year in Ethiopia, some of its new programs will be addressing serious social issues such as cross-generational sex, early marriage and the HIV situation among refugees.

New abstinence-only projects are planned, but some programs with an “Abstinence” and “Be Faithful” focus are now being complemented with the “C,” or condom education, component. A project aimed at Addis Ababa University students, for instance, shifted from AB to ABC in 2006. Government documents describing PEPFAR’s “other prevention” activities (which include condom education) for Ethiopia state: “One new target population is university students who engage in risk behavior despite AB interventions.”

Meanwhile, in the Djibouti corridor, there isn’t a lot of good news for the commercial sex workers assisted by Save the Children’s program. The American NGO submitted a proposal to USAID requesting PEPFAR funds for a program that would create small business opportunities for women engaged in sex work.

“Most commercial sex workers are in the business because of poverty, family problems or early marriage,” said Abiy, the HRCI prevention programs coordinator for Save the Children. “They tell us: ‘Why don’t you help us get out of this life?’ ”

Abiy said USAID turned down Save the Children’s proposal. When asked about that, USAID officials didn’t offer an explanation but said they are funding other similar initiatives in Ethiopia, although not for sex workers.

All the women interviewed by ICIJ in the Djibouti corridor said they would leave commercial sex work if they were given another job opportunity. “We want to be self-reliant,” said Selam Aregaya, the woman whose three friends tested positive for HIV. “We left our families in search for a better life. If we get funding, we could organize ourselves and open a small cafe or make injera [a pancake-like bread eaten in Ethiopia] for the local restaurants.”

Aregaya and the three young women with her said they could relate to PEPFAR’s teachings on abstinence and fidelity if they had a different job.

“Anybody can abstain and be faithful if they have shelter and food,” said Alma Legesse, a 23-year-old sex worker and a mother in NazrÄ“t, who has been trained on HIV prevention by the PEPFAR-funded program. “But if I sleep in the street with no work and no one to protect me, I need to have condoms.”