Nepal has accelerated the pace of reforms aimed at curbing financial crimes, under pressure by international anti-money laundering watchdogs and media exposés, over the last few years. Now the country has to prove the new policies are working.

After the then-central bank governor warned in 2019 that Nepal could be labelled as a country with “significant deficiency” in its anti-money laundering practices if its financial institutions didn’t step up their game, the country introduced disclosure rules for high ranking officials.

Under review by a regional watchdog, the country also updated its guidelines on how banks can identify and flag suspicious transactions ー after which, Nepal’s financial intelligence unit saw a 50% increase in suspicious activity reports filed, according to media reports.

Just a decade ago, the Asia-Pacific unit of the Financial Action Task Force found that Nepal lacked due diligence laws for financial institutions and other measures to prevent money laundering, citing government figures in a report that documented an “horrific picture of impunity” and “slow” government response.

“The first step in countering anti money laundering and illicit behavior in general is to have policies in place,” said Kasper Brandt, a Copenhagen University researcher and economist who studies illicit money flows in developing countries. “It’s great to see that they are trying to adhere to international standards.”

But that’s not enough to prove the policies aren’t just “for the show,” Brandt said. The next steps, he said, should be enforcement and data collection to be able to monitor, prevent and punish potential crimes. “You need to dig deeper and see: what are they actually doing?”

In 2019, Kathmandu-based journalists at the Center for Investigative Journalism Nepal analyzed thousands of confidential records leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and other media partners between 2013 and 2017, including Panama Papers and Swiss Leaks.

Access to the documents allowed CIJ Nepal to document the use of tax havens by Nepalese business people and politicians for the first time, and examine its impact on the country’s economy.

Their NepaLeaks investigation showed how a big part of funds flowing into Nepal as foreign direct investments came from tax havens and that some of that money belonged to companies that had previously been charged with tax evasion.

In response to CIJ Nepal’s exposé, the government established a committee to review potential irregularities in the foreign direct investment system and later found that 27 companies had brought more than $90 million into the country unlawfully.

ICIJ’s Scilla Alecci spoke with Nepalese partners Krishna Acharya and Ramu Sapkota to learn more about the reforms and the status of financial reporting in the country.

What is the biggest challenge in reporting on financial crimes in Nepal?

The concept of digital governance has just started in Nepal. The Office of the Company Registrar publishes general information related to companies on the website and other financial sectors where money laundering takes place have not been digitized yet in Nepal and their details cannot be found in public. Those include cooperatives, banks and financial institutions, real estate, revenue and tax administration, import-export, gold and precious metals traders. To see some details related to this, we have to go to the concerned government office and turn over the file, where there is a risk of not getting full details.

Financial sector reporting is often based on data made public by government agencies. For example, there has been a lot of reporting on whether foreign direct investment (FDI) has increased or not. But finding out the details is challenging. Details of how much foreign direct investment has flowed into Nepal from the British Virgin Islands are easily available but it is difficult to find out information on the investors, how much money has been deposited and which policy decision taken by the government has favored such investment. It is also difficult to find out which banks were punished by the Nepal Rastra Bank [Nepal’s central bank] for facilitating money laundering.

What’s the level of data transparency in your country?

Many government agencies do not have electronic record keeping systems so we have to look for the files manually. Information on beneficial ownership is available if we file the application of Information at the Office of Company Registrar. But even if data is available, we can’t be sure whether it is complete or not.

Not only data, overall transparency in our country is very weak. The Constitution of Nepal has a provision that says that “every citizen shall have the right to seek and receive information on any matter of his or her own or the public interest.” A provision also allows journalists to request information to public bodies on the basis of the right to information but some information cannot be obtained easily.

At the same time, some laws and constitutional provisions have created more problems for financial reporting.

The constitution itself states that “no one shall be compelled to disclose information which is required by law to be kept confidential.” According to this provision, laws have been made to keep investors’ property confidential. That means that a public body is not obliged to give details on how much money a person has received in the form of remittance or FDI from another country, how much tax has been paid and in which companies that person has invested.

Despite all this, we are still reporting. And that is possible thanks to reporters’ personal relationship with their sources and the support of the government officials who want good governance.

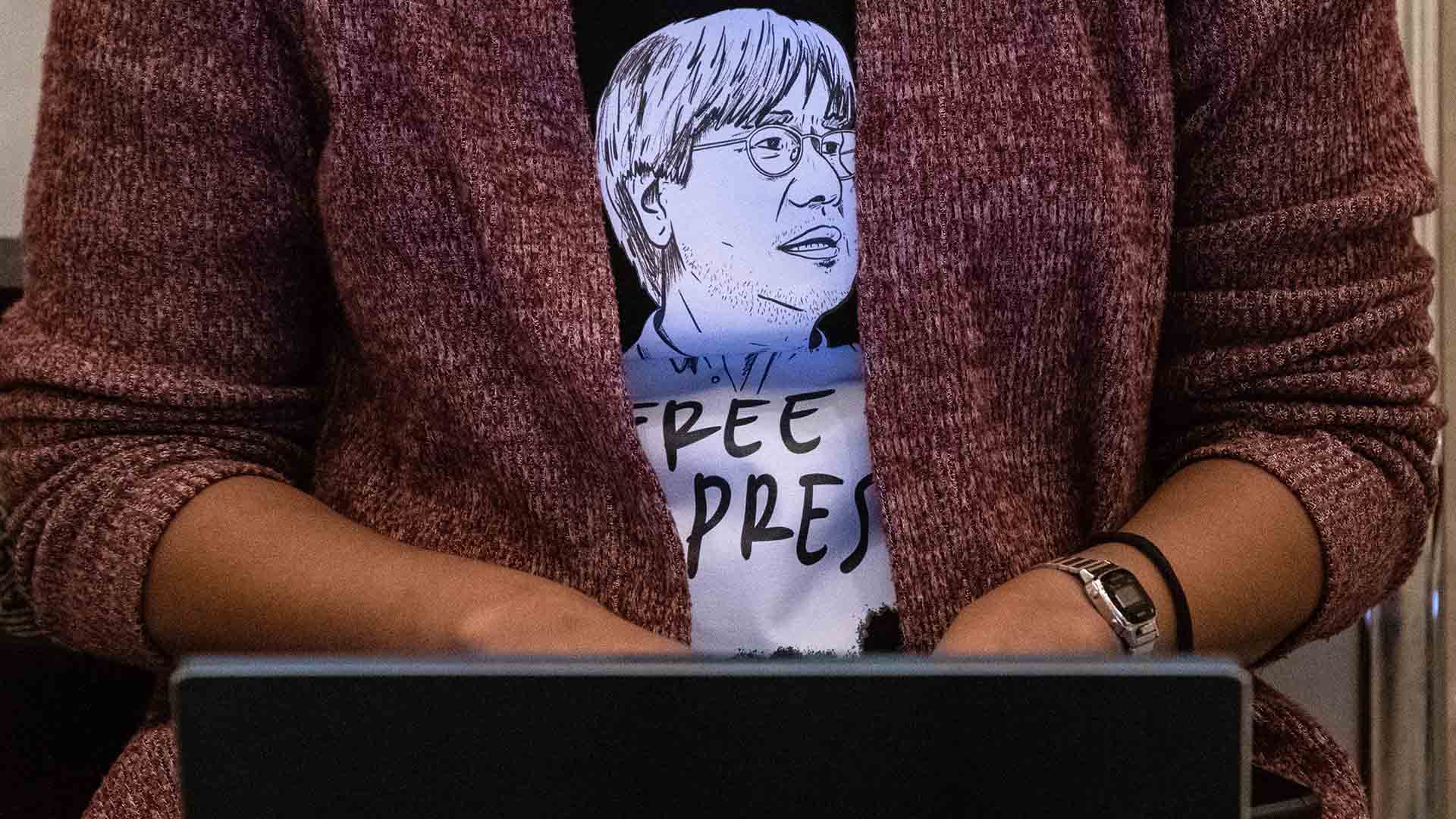

Did you face threats or intimidation for your NepaLeaks or FinCENFiles reporting?

While we were trying to get comments from Nepali business people, sometimes we would get threats from them. Some of them told us that they would file a case against us with the police. Others pressured us not to publish the news about them. Sometimes they used other people to know about our reporting and would call us to learn about our identity. Somehow it feels like psychological pressure on us.

After NepaLeaks was published, in February 2019 a businessman named Rajendra Bajgain filed a defamation suit against Shiva Gaunle, the then-editor of the Center for Investigative Journalism, in the Lalitpur District Court, alleging that our article had insulted him. But the Court found in favor of CIJ Nepal saying that the plaintiff’s “claim cannot be sustained.” [Editor’s note: Gaunle is an ICIJ member.]

How have the leaked data published by ICIJ helped you report on Nepali businesspeople and uncover potentially illegal transactions?

The leaked data published by ICIJ is useful for our reporting and it is the backbone of our stories. In the past, the revelations of ICIJ’s Swiss Leaks, Offshore Leaks and Panama Papers were of interest as soon as Nepal’s name came up, but simply searching on ICIJ’s public database wouldn’t allow us to obtain many details. Because there are so many people with the same name, it was difficult to tell who was involved in what crime.

When ICIJ gave us access to the data, we got to do in-depth research and were able to link the financial crimes committed by people linked to Nepal. ICIJ’s data also boosted our confidence during the reporting. Nepal’s Department of Money Laundering Investigation and other regulatory bodies have also conducted research on the basis of the news published using the ICIJ data.

How do you view the new bill on disclosure requirements for high-ranking officials and your government’s recent actions regarding money laundering?

The new bill is a landmark decision and was released by the government after we published NepaLeaks.

But in the case of Nepal, the rules brought by the government regarding anti-money laundering are not enough, because all the laws that have been enacted so far have been made binding.

These have been brought in to comply with the standards set by international organizations such as the European Union, the Financial Action Task Force and the Asia Pacific Group.

The FATF and APG are assessing Nepal’s money laundering practices Some of the current policies are also motivated by the objective of avoiding ending up on the black list. Nepal has yet to work on real issues of corruption, opacity and financial malpractice rather than showing off by endorsing rules and regulations. Therefore, we still need to wait to see how the government implements this new bill.=

This interview has been edited for clarity.