The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists collaborates with hundreds of members across the world. Each of these journalists is among the best in his or her country and many have won national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

This month, we spoke with Colm Keena, a reporter at The Irish Times, who’s been covering business and political corruption for decades. He even wrote a story that resulted in a landmark Supreme Court ruling in Ireland, defending the right of journalists to protect their confidential sources. Keena has been a member of ICIJ since 2014, and most recently worked with ICIJ just last month on a story about one of Ireland’s most notorious crime gangs.

ICIJ’s award-winning Meet the Investigators series is emailed exclusively to ICIJ’s Insiders each month before being published on ICIJ.org, and is one of a number of ways we like to thank our community of supporters who are so integral to our independent journalism. You can join our Insiders community by making a donation to ICIJ. Thanks to all our ICIJ Members who have shared their stories with us, and to all our supporters for helping ICIJ continue its work.

TRANSCRIPT

Nicole Sadek: Welcome back to Meet the Investigators from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. I’m Nicole Sadek, ICIJ’s editorial fellow.

Today I’m speaking with an Irish journalist who was once a public affairs correspondent-turned legal defendant. I know, it sounds like a movie — and a good one. But before we get into that, let’s start, as we always do, with introductions.

Colm Keena: My name is Colm Keena, and I’m a reporter with The Irish Times in Dublin, Ireland. I’ve been working for The Irish Times since the middle of 1990s. And I’ve been a member of the ICIJ for many years.

Nicole: I’ve learned since beginning this podcast that most journalists don’t have a very straightforward path into journalism. Is that something that applies to you? How did you get into it?

Colm: I studied zoology in university. I then traveled around, did odd jobs, and then I thought I’d like to get a proper job and applied for a course in the law or a course in accountancy or a course in journalism. And only the third journalism college responded to me, so I became a journalist.

Nicole: Today, Colm is a leading Irish journalist who’s broken some of the biggest business and political corruption stories of his generation. His career-defining story kicked off in 2006. That’s when he received classified documents indicating that an Irish tribunal was quietly investigating improper payments made to the leader of Ireland, Bertie Ahern. Colm took the documents from his confidential source, or sources, and published a front-page story for The Irish Times. It was a bold move, and the tribunal wasn’t happy about it.

Colm: The tribunal wrote to us, and told us to hand over any documentation that we had. And then we took legal advice — myself and the then-editor Geraldine Kennedy, a very well-known journalist here in Ireland. The advice was that we have to obey the law just like everybody else. Having received legal advice, we then shredded the documents and told the tribunal that we’d shredded the documents. And then we were ordered to appear before the tribunal. And we explained that we really, really didn’t want to be put in a position where we were defying the tribunal, but that we had felt there was an obligation on us to protect our sources. So the matter then went to court because we wouldn’t answer any questions that went to the topic of the source or help them identify the source. I felt very, very uncomfortable about it and still do.

Nicole: Even though Colm was deeply uncomfortable — and facing possible jail time for being in contempt of court — he also found the process fascinating. The court, usually an opaque institution for Irish journalists, was suddenly very transparent.

Colm: I’ve always been interested in public life, usually from the back of the room, you know, scribbling in a notebook, and suddenly I was in the public life. As a reporter, you often find yourself trying to find out what happened when they went into the meeting. You know, and you try to ask people when they come out, you know, privately, “What did he say? What did she say?” But this time, I was actually in the meetings, you know, inside, talking to people and so on, so I enjoyed that.

Nicole: Colm and his editor Geraldine lost at the High Court.

But then they appealed. To the Supreme Court.

Colm: The Supreme Court decided that under the European Convention of Human Rights, we did have a right to defend the confidentiality of our sources, but that we’d been wrong to take the law into our own hands, and we should have trusted the legal system. But it did establish a landmark judgment in Ireland in terms of defending the right of journalists to protect the identity and anonymity of their sources.

Nicole: Colm stands by his decisions until this day, and says he’s proud of the story.

Colm: The editor held a meeting in the newsroom to address the staff about it, you know, and said, it was the best story in a quarter of a century. So I was really proud. And I’ll just tell a funny anecdote. I went on a trade mission with the government about a year after the story, and it was led by Bertie Ahern who was still taoiseach [prime minister]. And he came up to me and said, I’m glad to see you’re coming on the trip, and gave me a friendly little tap on the shoulder, but it wasn’t really. It was quite a forceful tap on the shoulder with a fist. I was a little bit sore actually. And you know, I live not too far away from where he lives now. And we bump into each other in the butcher shop and so on. So you know, Ireland’s a small enough place, but yeah, so I was proud of the story.

Nicole: Even though Colm and Geraldine won the right to protect their source, the Supreme Court reprimanded them for shredding the documents and said they would have to pay the legal costs for the tribunal — remember, the one that the documents came from in the first place. It was a whopping €550,000.

Colm: It was a lot of money, and it was a lot of money for The Irish Times. Although The Irish Times is a very influential institution in Ireland, it’s not a hugely powerful one financially. But I must say, the commercial side of the house were fully behind the editorial side of the house. In fairness, the staff generally of The Irish Times, saw that it was the right thing to do. And it was in that way, it was kind of morale boosting for the organization.

Nicole: Press laws have always been a sore spot for Irish journalists, especially those surrounding defamation. Are the defamation laws so constraining that it almost enables corruption?

Colm: It does inhibit journalists from doing their job and holding power to account, and that’s just not special pleading. I mean, it really is a problem. Really what we need is for some way that, you know, public interest journalism that’s done in good faith can’t involve defamation cases that, you know, close newspapers down or damage them severely.

Nicole: Colm joined ICIJ as a member in 2014. Since then, he’s contributed to various projects.

Colm: I really enjoy working with other journalists from other jurisdictions and other cultures, or the media, like TV and so on. Ireland’s kind of a small place, so it’s just good to get off the island every now and then.

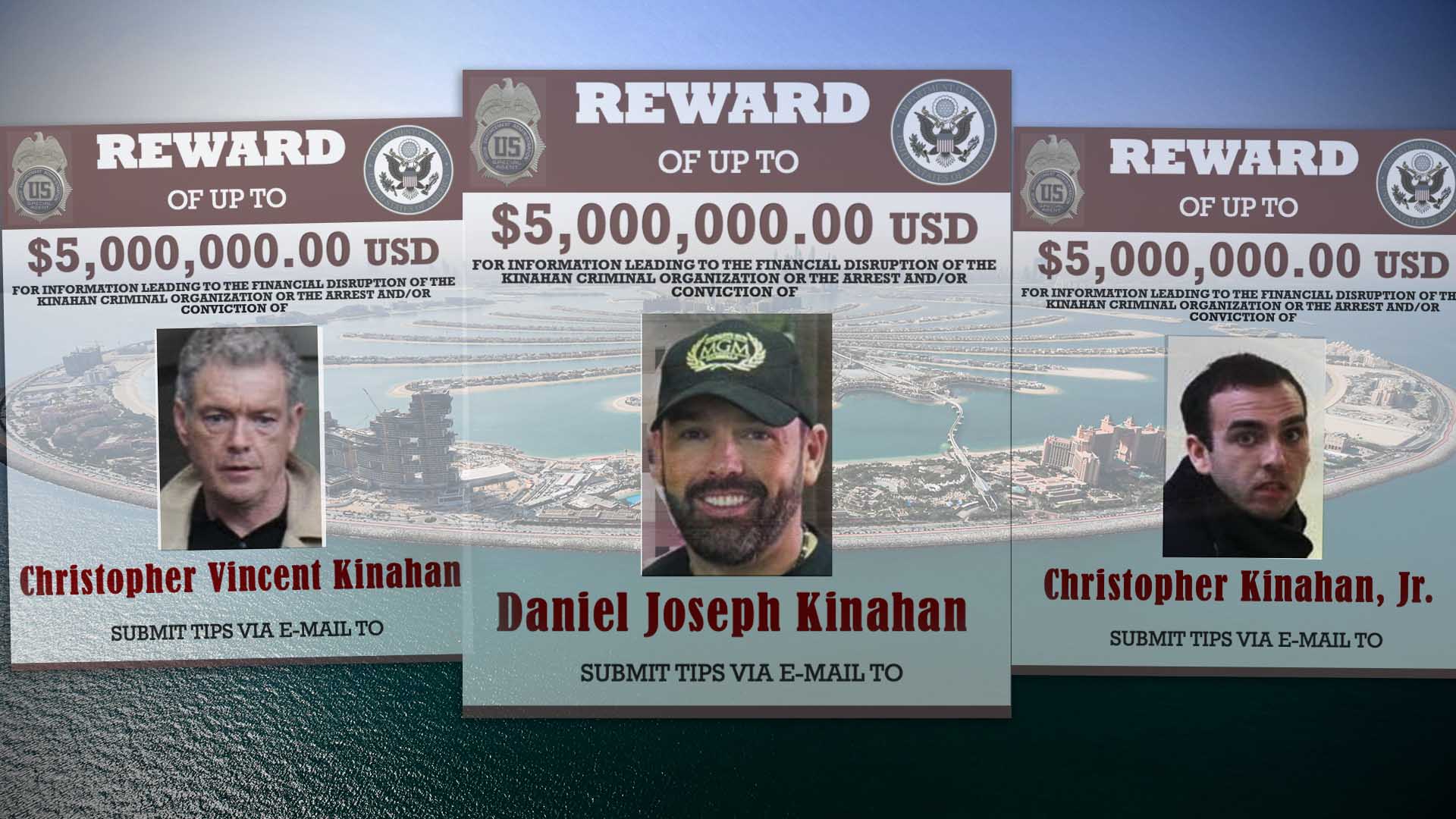

Nicole: Colm’s most recent project with the consortium involved uncovering the companies behind one of Ireland’s most notorious crime families. They’re called the Kinahans and they’re known for their drug smuggling empire. Earlier this year, U.S. authorities sanctioned some members of the Kinahan family.

Colm: The ICIJ then contacted myself and The Irish Times a while ago and said they had some leaked documents that come from Dubai and mention the Kinahans. And you could see that around the time that these Kinahans had moved to Dubai, they started to set up these legitimate companies and have dealings with the Dubai authorities to get special tax free zone. And it was obvious from the documents that there were even know-you-client-type documents in it. So, you know, there was no doubting that they knew it was Daniel Kinahan, Christopher Kinahan that they were dealing with. So despite it being obvious who they were dealing with, it’s obvious the Dubai authorities had no concern at all.

Nicole: How was this project different from previous stories you’ve written about offshore companies?

Colm: I’ve been writing about the offshore world for quite some time, but I’d never really focused in on on the extent to which the United Arab Emirates is part of that offshore world and not just part of that offshore world, but shamelessly so, and perhaps sees it’s in its interests to deal with what one of the experts I spoke to calls the gray economy. It would rather deal with the dodgy business people and dodgy business practices and low standards and so on because it thinks there is more money in it out there.

Nicole: It seems that in Ireland you and your colleagues have been covering it maybe more intensely for a longer amount of time than people elsewhere in the world.

Colm: Like I say, I live in Dublin, and we have an area of the city that’s full of all these American multinationals: Google, Facebook, you know, Twitter. They’re all here, and we call it Silicon Docks. It’s down at the docks. And the model is that you set up these headquarter operations here in Dublin, and if you want to avail of the tax advantages of being here in Dublin, you really need a substantial business operation. And so that’s why they have these very substantial business operations here and people getting very well paid. But it has a great tax advantage to them. And they set up these elaborate global networks where all the money flows into Dublin, from around the world for sales outside the United States. And this money ends up in places like the Cayman Islands. And I as a reporter in The Irish Times business section used to spend a lot of time covering that.

Nicole: One of the larger projects Colm took part in was the Implant Files, a 2018 ICIJ-led investigation that involved more than 250 journalists from around the world.

Colm: I mean the focus of the Implant Files was about maybe the requirement for better regulation of medical implants because when it goes wrong, it’s such a disaster.

Nicole: But his contributions to this project went beyond traditional reporting. As he was secretly working on the project, he suddenly learned he’d have to get a medical device implanted into himself, so he decided to write a first-person account.

Colm: I was walking in the mountains outside Dublin. And I noticed when I was going up steep slopes, I had a strange sensation in my chest. And then when I was on the level I was fine. So I went to my GP and she said, “Okay, I want you to leave here and not go to work and go straight down to the hospital.”

Nicole: After conducting some tests, doctors found one of his arteries was 80% blocked. A surgeon recommended a stent.

Colm: So then he brought me into the theater, and they don’t knock you out. They have to keep you awake. But they do give you something to calm me down. And then they put this thing in your wrist, and go up through your arterial system, and look into your arteries going into your heart, and you can see it all on the big screen, you know, and discuss it with the guy. He was a really nice guy. And so I was ready to tell him that I’ve been working on an implant files story. And, and that, you know, the stents that he was how going to put in were one of the topics we covered, and we had a good laugh about it, you know, and, but the whole thing was over in 45 minutes, you know, and, you know, that was a good few years ago. And you know, and the benefits for me have been huge. On a personal level, I thought what happened to me just showed you how wonderful these implants are.

Nicole: In addition to his investigative work, he’s also an author. He’s written a handful of books about Irish politicians, but he also published a novel, called “Bishop’s Move,” about a bishop who lands in trouble with the church and with the government.

Colm: I took some time out. I went traveling with my family and then I think I just had the mental capacity and space to focus on the story that I’d made up, and try to write it start to finish. And I just found it a really satisfying thing to do. Part of the narrative that I wrote has to do with political corruption and powerful figures in our society. And I also introduced the Catholic Church into it, which, of course, is a huge story, maybe the biggest story over my lifetime for us journalists here. So I just I found that of interest. I wasn’t trying to make any political point or any point in public affairs when writing the book, but I really enjoyed working on it.

Nicole: Have you thought about writing any other novels?

Colm: Yes. And next week, I’m disappearing off the grid for three months on paid leave, and I shall, that’s exactly what I’ll be doing. Whether I’ll succeed in doing anything or not, I don’t know. But I decided it was time to give it another go. So, you know, the COVID we’re all working from home since COVID started and so on. It’s been a difficult enough few years. So I gotta give myself a bit of a break.

Nicole: Good, I think we all deserve it at this point.

Big thanks to Colm Keena for joining me today. Don’t forget to share this episode on social media using the hashtag #MeetTheInvestigators.

Meet the Investigators is a production of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. This episode was produced and edited by me, Nicole Sadek, with help from Hamish-Boland Rudder. We’ll be back again next month.

If you’re a fan of our Meet the Investigators series, please consider making a donation to support ICIJ. Not only will your donation help support our work with journalists like Colm, but as an ICIJ Insider, you’ll also receive sneak previews, access to exclusive chats with reporters and behind-the-scenes content like this delivered straight to your inbox. Donate today, and support independent investigative journalism.