MEET THE INVESTIGATORS

‘All journalists should be investigators at heart’

ICIJ member Golden Matonga shares stories of exposing government corruption and doing his part to ensure democracy endures in Malawi.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists collaborates with hundreds of members across the world. Each of these journalists is among the best in his or her country and many have won national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

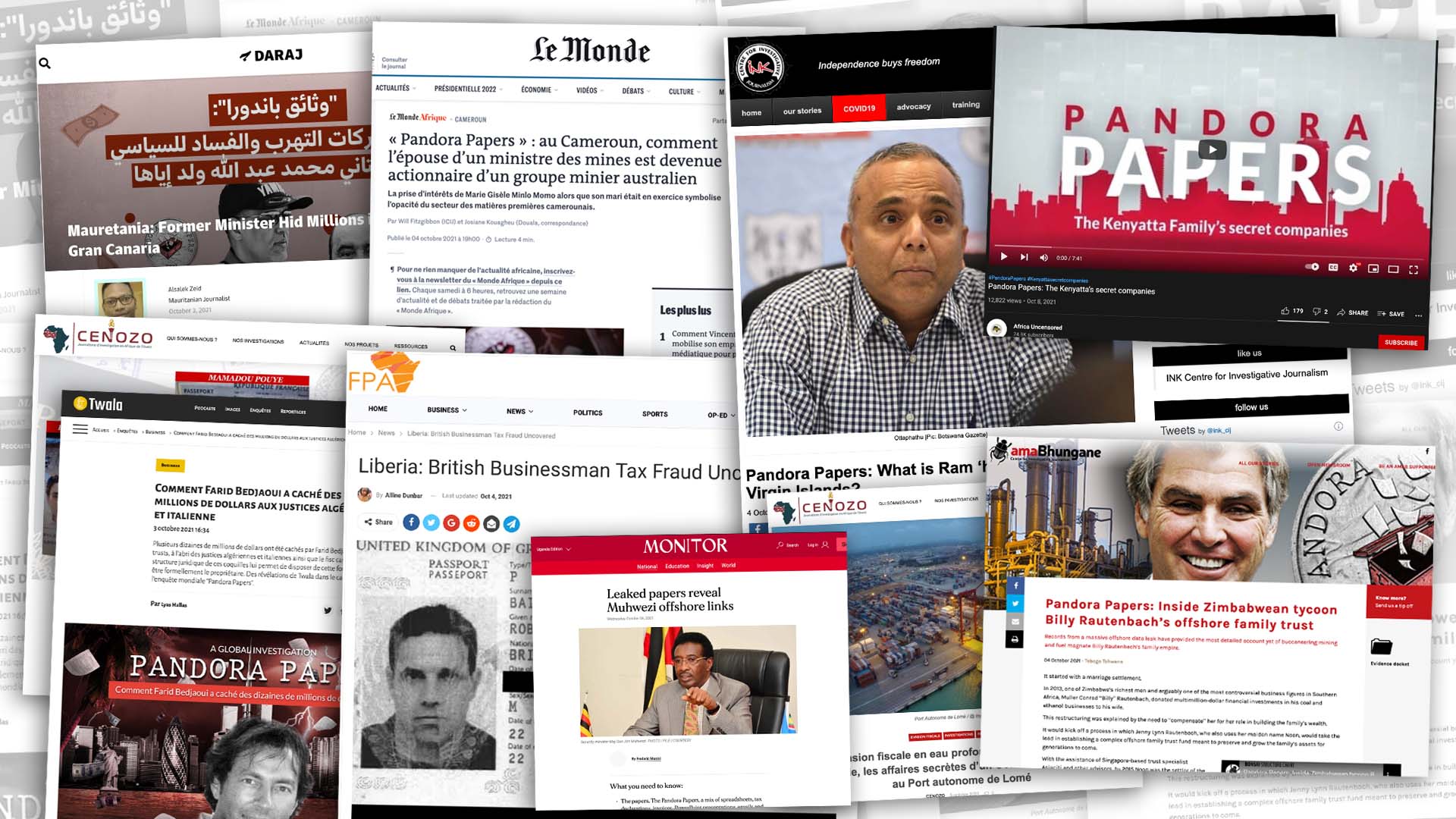

In August, we spoke with Golden Matonga, a Malawian reporter who is the investigations director at the Platform for Investigative Journalism in Malawi, and who’s written for various outlets, including Nation Publications Limited, the Telegraph and the Financial Times. Matonga has covered everything from an international criminal to a botched presidential election. As a member of ICIJ since 2021, he’s worked on the FinCEN Files and Pandora Papers.

TRANSCRIPT

Nicole Sadek: Welcome back to Meet the Investigators from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. I’m your host, Nicole Sadek, ICIJ’s editorial fellow.

I’m excited to introduce you this month to ICIJ’s Malawian member Golden Matonga, based in the nation’s capital Lilongwe. Since he got his start in journalism 15 years ago, he’s become one of Malawi’s most respected reporters. He’s covered a disputed election, an international criminal and a fair share of government corruption. He was named Malawi’s Blogger of the Year three years in a row, and Columnist of the Year in 2018.

But like others we’ve met in this series, a young Golden had different plans for his career.

Golden Matonga: I thought I was going to be a soccer player. I only realized after high school when I had to start college that I needed to do something else to just make sure that I have a fallback plan. That made me look at what other things was I passionate about. And I realized that I had a passion for writing. There was one columnist, the late Ralph Tenthani — he used to write the Sunday column — and I fell in love with his column. Everyday, he was speaking truth to power, and that hooked me. That was way before I realized that I would have a passion in investigative journalism. For me, it was just more of being able to communicate to the leadership of a country and to communicate to decision makers, which really inspired me.

Nicole: Today, Golden is the investigations director at Malawi’s Platform for Investigative Journalism, or PIJ for short. PIJ reports wide-ranging stories on government wrongdoing. The organization’s original mission, however, was more than just publishing stories.

Golden: Resource is a big challenge, even in the advanced economies. Journalists everywhere, they’re always complaining that resources are not enough. But I think it becomes an even more pressing issue when you are looking into an economy like Malawi, where media houses are really struggling to make ends meet. So PIJ started providing these grants and also started providing trainings to journalists. So that was the core work of PIJ. But over the years, because of experience with the challenges with Malawian media outlets publishing some stories — particularly those that bring to account our corporate entities and powerful organizations — PIJ decided that it should start publishing most of the investigations itself. So we have shifted most of our focus away from just supporting journalists to do independent work to publishing most of the work ourselves. We do not subscribe to any interest groups. We do not have advertisers. We solely depend on the grants and donations to do our work.

For Malawi’s democratic experiment to be effective, we believe that we should provide the oxygen of information to the public.

Nicole: I noticed that the motto of PIJ is Digging Truth, Lighting Democracy. What does that mean?

Golden: For Malawi’s democratic experiment to be effective, we believe that we should provide the oxygen of information to the public. So we believe that only when the public knows the truth, that’s when we are going to hold duty bearers to account.

Nicole: Democracy was exactly what was at stake in 2019, when Malawians went to the polls to elect a president. Once ballots were cast, people started worrying that a correction fluid similar to White-Out had been used to manipulate the votes.

Golden: The election itself went peacefully, but it was only later when the counting of a vote started that rumor started circulating that the election had been doctored. There have always been all these rumors and allegations of election manipulation in the past in previous elections, as well. But something changed in this election. Because of technology, social media platforms, for the very first time, Malawians started seeing what was seen as evidence of the actual manipulation.

[Audio clip from Al Jazeera English]: Opposition supporters in Malawi say last year’s election was rigged to favor Peter Mutharika, who narrowly won reelection over opposition leader Lazarus Chakwera. For months, there’ve been demonstrations in several parts of the country, including the capital, Lilongwe.

Golden: I remember covering those elections, and I think it will be one of my strongest memories when I’m out of journalism. Some of the protesters were angered by the fact that I was taking pictures, and they harassed me, physically, almost assaulted me. And I lost some of my equipment along the way. So, it was a difficult time for journalists to tell the story from that perspective. But largely the media I think was free enough to report on what was happening. We had access to the court premises, we had access to the political players. So generally speaking, I wouldn’t complain knowing what challenges other journalists elsewhere face. That also reminds me that at some point I was arrested. I almost forgot that I was arrested while covering some of the election stories.

Nicole: Golden had been sent to the capital airport to interview a delegation of election observers from the EU, when police officers demanded that he and his colleagues stop their work. They were later arrested and thrown into a cell for hours.

Golden, were you scared when you were arrested?

Golden: I think the most prevailing feeling was anger. I was absolutely angry when I was arrested for not doing anything wrong. I was treated as a criminal, bundled into a police cell. I think, for me, fear was the last thing on my mind. I was angry, I was shouting at the police officers. I remember not being violent, but really being quite emotional in my reaction because I couldn’t understand in this day and age, why someone would consider journalism a crime. And Malawi has been a democracy for 25 years, one of the most stable democracies on the continent. And I just found it unacceptable that someone could decide to employ heavy handedness on journalists for simply doing their jobs. And we only released after media watchdogs released statements demanding our release. It didn’t really change the way I conduct journalism. I went on to do even more, more sensitive work than before after that. I think it inspired me that I had an important job to do, but it didn’t change my calculation in how I do it.

Nicole: In the end, the election was nullified. Malawians went to the polls once again, and the opposition leader was elected.

This year, Golden’s reporting on a businessman’s connection to Malawian officials made a big splash. Zuneth Sattar, a Malawian-born Brit, ran a massive bribery campaign in exchange for lucrative contracts from Malawian ministers. The story involved some of the highest members of government. After it was revealed that ministers in his own cabinet had corrupt dealings with Zuneth Sattar, the president made a bold move and dissolved his entire cabinet.

[Audio clip from Make Afrika Great]: In exercise of the powers vested in me by the constitution, I have dissolved my entire cabinet effective immediately, and all the functions of cabinet revert to my office until I announce a reconfigured cabinet in two days.

Nicole: Golden, what’s been the experience of covering this story?

Golden: This is a story beyond the normal, everyday corruption that we report on. This is a story about state capture corruption. So it means the involvement in the levels of government is way higher up. It means almost every level of government which you have been looking into has been involved in one way or another in the alleged corrupt dealings with Zuneth Sattar. We were able to acquire the contracts, we were able to analyze how the procurement was done, does it make financial sense for a poor country like Malawi to make payments to this guy? Most of the contracts were grossly overpriced in most circumstances. Most of the contracts did not follow any procurement laws.

Nicole: How were you able to obtain those contracts? Do the information laws in Malawi allow for access to those types of documents?

Golden: So primarily, all those contracts which we acquired, we acquired them through our sources. Through the access to information laws, we haven’t been successful yet, but we have been able to get the contracts through a number of our sources.

Nicole: After the attorney general stated publicly that the government should terminate the contracts with Sattar, Golden and his colleagues, got ahold of documents showing that the official had issued a private legal opinion saying the government should pay Sattar.

Golden: My boss, Gregory Gondwe, was arrested for the reporting because the Office of the Attorney General was mad, and they wanted to know the source of the official document. So, Gregory was arrested, handcuffed, and taken into a police car after the police came to our office and he told them that he couldn’t comply with their demands. And again, they forcefully grabbed his phone and laptop so that they could check for themselves who provided us the information which we published. So that was a huge attack on our independence because the whistleblowers could be in danger. People’s jobs were at risk, even possibly, their lives were at risk.

Nicole: Why is there so much government corruption happening in Malawi?

Golden: Accountability systems haven’t been functional for some time. And so there are a lot of incentives for people to conduct collaboration. And most of the corruption as well is connected to political financing. So we have politicians who are working with the business people to conduct political campaigns, and it’s these business people who are financing political campaigns, and this is not being regulated.

Nicole: Corruption has even reached the highest office in Malawi. Golden and his ICIJ colleagues discovered in 2020 that the former president, Joyce Banda, was implicated in the FinCEN Files, an investigation into how banks and the U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network did little to stop illicit financial activities. The leaked files suggested that the owners of an arms company called Paramount Group had made payments to a PR firm to prop up Joyce Banda’s image in exchange for government contracts.

Golden: The evidence wasn’t conclusive from the documents which we acquired. So we reached out to the former president and asked her questions. And we also reached out to to Paramount Group and they basically denied any wrongdoing, but at least for the first time, we were able to provide some evidence coming from the banks, indicating a relationship between the former president of Malawi and a major supplier who had provided the supplies to Malawi’s defense forces.

Nicole: How was the experience of working on your first international collaboration?

Golden: So the principle of radical sharing was one of the most eye-opening things that happened during my initial work with the ICIJ. So radical sharing basically means that ICIJ doesn’t believe in the parachute journalism, where they send someone from London to go to Malawi and do the interviews but believe that the local knowledge is much better for its work to be effective. I wasn’t a financial reporter. I still cannot say I’m a financial reporter, but over the years, the knowledge which I have attained from covering complex cross-border reporting financial crimes, like banking secrets, I’ve been able to translate to some of the work which I’m doing at the moment and my normal investigations because I’ve now developed contacts, I know the terminology, I have data sets which I have acquired over the years. So that as well enriched the work we have been publishing.

Nicole: Having all that experience, what advice do you have for younger or newer journalists?

Golden: Try to learn as much as possible, read what the best are writing, be able to ask where you don’t feel like you have adequate knowledge. And I think the rest will take care of itself along the way. Every journalist should be an investigator at heart. So what’s important is to be able to push yourself to see what can you get beyond the story which everybody else is getting?

Nicole: Are you reading anything now to enrich your knowledge of any subjects?

Golden: I’m still trying to understand how the world economy works. So I’m reading a book called The Wealth of Nations. It’s a book written by Adam Smith, one of the preeminent economists. So that’s a book I’ve been delving into the past couple of days.

Nicole: That’s the wrap of another episode of Meet the Investigators. Thanks to Golden Matonga for stopping by the podcast and for sharing insights into journalism in Malawi.

Meet the Investigators is a production of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. This episode was produced and edited by me, Nicole Sadek, with help from Hamish-Boland Rudder. Don’t forget to share the episode on social media using the #MeetTheInvestigators. We’ll be back next month for another installment.