When the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht S.A. admitted in December 2016 to a massive corruption scheme that the United States Justice Department described as the “largest foreign bribery case in history,” it set off a wave of political scandals across Latin America.

Governments toppled. Former presidents and other senior officials, along with Odebrecht executives, went from the halls of power to prison cells. Odebrecht confessed to a detailed accounting of its misdeeds and is cooperating with prosecutors across the region who have vowed to bring its collaborators to justice.

But Odebrecht’s confession didn’t tell the whole story.

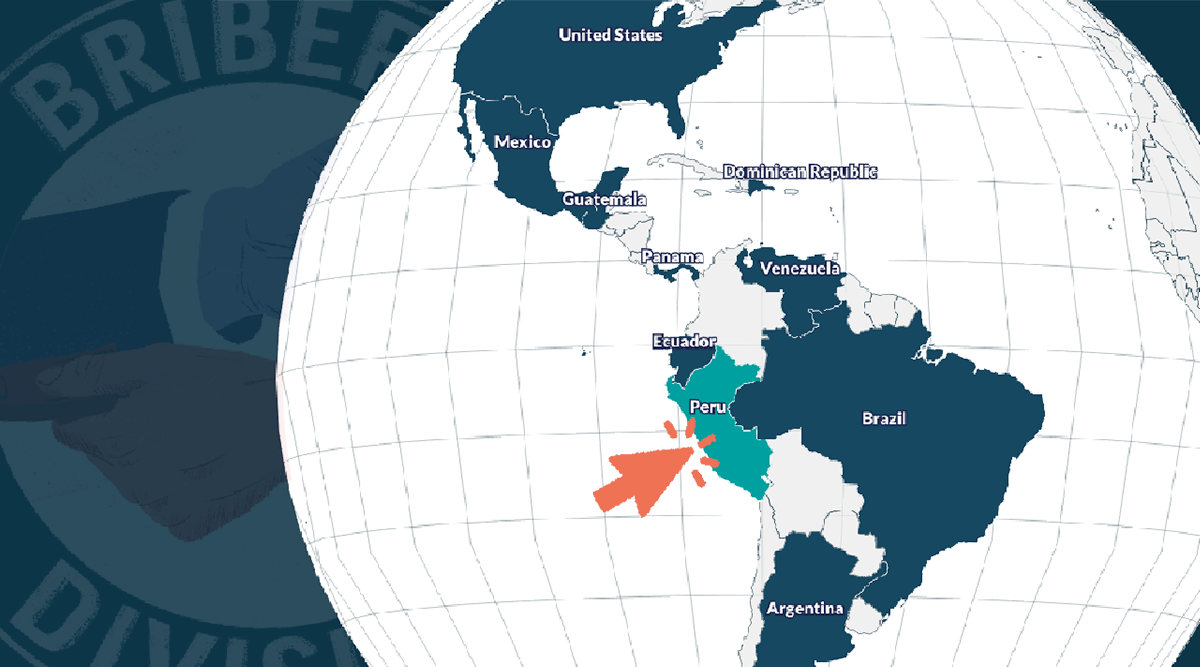

The Bribery Division, a new investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, reveals that Odebrecht’s cash-for-contracts operation was even bigger than the company has acknowledged, and involved prominent figures and massive public works projects not mentioned in the criminal cases or other official inquiries to date.

These discoveries were made in a fresh trove of leaked records from an Odebrecht division created primarily to manage the company’s bribes. The records were obtained by the Ecuadorian news organization La Posta and shared with ICIJ and 17 media partners across the Americas. The leaked records reveal hidden payments across the region that extend far beyond what has been publicly reported, including:

- More than $39 million in secret Odebrecht payments made in connection with the Dominican Republic’s giant Punta Catalina coal-fired power plant. Two official investigations into the project that reported finding no wrongdoing didn’t mention these payments.

- Seventeen payments totaling more than $3 million related to a Peruvian gas pipeline. Among those slated to receive payment was a company owned by a Peruvian politician who, in an unrelated recording recently aired by a local news station, appeared to plot the assassination of a rival.

- Emails discussing secret payments that a bank owned by Odebrecht operatives made to shell companies related to the construction of a $2 billion subway system for Ecuador’s capital, Quito. The documents don’t say who received the money.

- Payments related to more than a dozen other infrastructure projects in countries around the region, including more than $18 million linked to the subway system in Panama City and more than $34 million connected to Line 5 of the subway system in Caracas, Venezuela.

Odebrecht paid off public officials on such a scale that it created a special unit, the Division of Structured Operations, for the primary purpose of handling bribes. The files obtained by La Posta and ICIJ contain more than 13,000 documents that had been stored by this division on a secret communications platform known as Drousys. These files were obtained separately by the Ecuadorian news outlet Mil Hojas, which then joined in the project.

In Brazil, the epicenter of the scandal, former two-term president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, once described by Barack Obama as “the most popular politician on earth,” sits in prison serving a lengthy sentence for corruption and graft, including Odebrecht-related offenses. On June 17, Odebrecht announced it was filing for bankruptcy protection to restructure $13 billion in debt.

For more than four months, ICIJ has worked in partnership with more than 50 journalists in 10 countries to investigate the ledgers of Odebrecht’s bribery division.

In a statement to ICIJ, Odebrecht said it was committed to full cooperation with authorities investigating corruption associated with the company, and that it had shared the Drousys files with U.S. and Brazilian prosecutors. “Odebrecht will continue to make all efforts in a process of unrestricted collaboration with the competent authorities,” the company said.

The company declined to answer questions about individual cases.

Why did some remain hidden?

The Odebrecht scandal has been a continuing political earthquake shaking Latin America.

Revelations about illegal payments have toppled governments in Brazil and Peru and led to the imprisonment of former presidents of both countries. Across the region, prosecutors have filed a steady stream of indictments of public officials and others as new bribe recipients are uncovered.

But the leaked files make clear that Odebrecht’s web of corruption extended to many public works projects and public figures that have not been addressed by law enforcement, raising questions about whether Odebrecht has been fully candid with authorities and about the political will of some prosecutors to pursue cases.

Carlos Pimentel, executive director of the Dominican anti-corruption group Participación Ciudadana, said the graft associated with the Dominican power plant and the inadequacy of the government’s response undermines the credibility of the country’s political institutions.

“There is a system of complicity in the country for the enrichment of a minority, in the public and private sectors, based on the impoverishment of the majority,” Pimentel said. “That is what the Odebrecht case has left.”

The unmasking of the company’s corrupt practices has also caused political upheaval, sparking anger at established politicians and fueling growing instability.

“When all the traditional parties are delegitimized, it opens a lot of space for an insurgent populist,” said Yascha Mounk, a Johns Hopkins University political scientist who studies the global decline of liberal democracy.

After Brazil’s da Silva was barred from running for president again because of his conviction, voters decisively elected an ultraconservative former military officer, Jair Bolsonaro, who railed against corrupt elites and who once said that the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985 should have killed 30,000 more people.

The leaked files also laid bare the role played by the shadowy world of offshore finance, which made Odebrecht’s bribery division possible. While bribe beneficiaries were almost all in Latin America, the payments invariably flowed through a secretive archipelago of offshore shell companies and bank accounts.

It’s mind-boggling to even understand how this went on for so long

– Shruti Shah, Coalition for Integrity

Opaque offshore entities funneled hundreds of millions of dollars in secret payments through companies and banks in countries around the world, including the United States, China, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United Arab Emirates, Panama and Antigua. In one instance, payments passed from Odebrecht through a company incorporated in the Bahamas to one with an address in the Dominican Republic, which later bought a $2 million apartment in midtown Manhattan.

All told, Odebrecht paid more than $788 million in bribes from 2001 to 2016, resulting in $3.3 billion in ill-gotten benefits, according to the U.S. Justice Department.

“It’s mind-boggling to even understand how this went on for so long,” said Shruti Shah, president and CEO of the Coalition for Integrity, a Washington-based nonprofit group that advocates stricter controls to curb corruption in business and government.

Rise of Odebrecht

Odebrecht was founded in 1944 by Norberto Odebrecht, a descendant of 19th-century German immigrants, in the Brazilian port city of Salvador da Bahia. His father had owned a construction company that shut down under pressure from high wartime materials prices.

Over the decades, Odebrecht became Latin America’s largest construction company, and governments across the region relied on it to carry out major public works from dams to highways to power plants.

The company attributes its success to a lofty set of “principles, concepts and criteria” it calls Odebrecht Entrepreneurial Technology, developed by its founder. These tenets include “Education through Work,” “Partnership among Members” and “Trust in People”. Its leadership has stayed in the Odebrecht family, with its presidency passing from Norberto to his son, Emilio, in 1991, and his grandson, Marcelo, in 2009.

Under the leadership of Marcelo, a slim, bespectacled executive once known as “The Prince,” the company’s annual revenues skyrocketed, from $17.5 billion in 2008 to $45.8 billion in 2014. Bidding successfully for blockbuster projects — including the $7 billion gas pipeline in Peru, the $2 billion Dominican coal-fired power plant and the $2 billion subway system in Quito — Odebrecht solidified its status as the dominant contractor in Latin America and became one of the largest contractors in the world.

Odebrecht benefited from close ties to the influential Brazilian President da Silva, whose administration tapped the company to carry out infrastructure projects that were part of his ambitious anti-poverty and development agenda.

But the company’s rapid growth under Marcelo Odebrecht was also powered by another factor: massive graft.

The scale of Odebrecht’s bribery operation became such that in 2006 the company created a specialized unit to manage it. The Division of Structured Operations “effectively functioned as a bribe department,” according to a statement of facts that the company acknowledged to be “true and accurate” as part of its plea agreement with the U.S. Justice Department. All of the unit’s payments were off the books, the division’s former treasurer Fernando Migliaccio would later testify to Peruvian prosecutors, and therefore illegal.

However, not all payments by the division were bribes, the company has said.

“Various works by the company are registered in these systems,” Odebrecht’s Peruvian division said in a July 2018 statement, in reference to Drousys and another off-the-books platform used by the Structured Operations unit. “This does not mean that all of them involved corruption or bribes.”

Inside the bribery division

The Division of Structured Operations combined the stealth of a criminal conspiracy with the bureaucracy of big business.

To communicate secretly, the bribery division created the Drousys system, an off-the-books platform including secure emails and instant messages.

Odebrecht employees and bribe recipients are referred to only by code names, many of which have yet to be cracked. Employees go by names such as “Gigo” and “Waterloo,” while recipients are often assigned more colorful monikers, such as “Bambi,” “Robocop,” “Darth Vader” and “Stalin.”

The documents include frank and explicit discussions about how to ensure the secrecy of the system. One email string is a discussion of the need to break multimillion-dollar payments into smaller increments to avoid making banks suspicious.

There also are spreadsheets that track the bribery division’s payments. One lists more than 600 outlays totaling more than $230 million issued from late 2013 through 2014.

Among the projects that the unit’s secret payments helped steer to Odebrecht, criminal investigations would reveal, were the rapid-transit system in Lima, Peru; a dam in Michoacán state, Mexico; and a hydroelectric power project in Ecuador.

Odebrecht’s system of corruption was finally brought down by Brazilian prosecutors in the famous anti-corruption investigation called Operation Car Wash. Launched in March 2014, the probe initially focused on money laundering at small businesses such as car washes, but it expanded when the dirty money led investigators to a huge bribery and bid-rigging conspiracy involving Brazil’s state-owned oil company, Petrobras, and Odebrecht.

In June 2015, Brazilian authorities investigating bribery, bid-rigging and overbilling on state contracts arrested Marcelo Odebrecht. In March 2016, a Brazilian court sentenced him to 19 years in prison, which was later reduced and converted to house arrest in return for his cooperation with authorities.

In December 2016, the Odebrecht company reached a plea agreement with prosecutors from Brazil, the U.S. and Switzerland, the latter two countries having joined the case upon finding that the company’s illegal payments had passed through Swiss and U.S. banks. The firm avoided prosecution by consenting to a detailed public statement of its crimes and agreeing to pay a fine of $2.6 billion.

The plea deal’s 23-page “statement of facts” lays out in detail the creation of the Division of Structured Operations and its purpose. Odebrecht admitted that the division funneled off-the-books funds through offshore companies and banks based in financial-secrecy havens, sometimes using fictitious contracts to cover its operations. The money was ultimately used to pay bribes to politicians, other public officials and political parties.

As part of the mandatory disclosures, Odebrecht handed prosecutors documents including spreadsheets tracking hidden payments, statements from offshore bank accounts, emails, transaction records, contracts and computer logs, all stored on its Drousys system.

Odebrecht’s revelations sparked outrage and unrest across Latin America. The arrest of former Brazilian President da Silva on Odebrecht-related charges touched off street clashes between his supporters and detractors. In the Dominican Republic, anti-corruption protesters in the Movimiento Verde (green movement) demanded an end to impunity for politicians entangled with Odebrecht.

The cooperation agreements and confessions generated high-profile charges. Former Ecuadorian Vice President Jorge Glas sits in jail after being convicted of taking bribes from Odebrecht. Former Peruvian President Ollanta Humala faces corruption charges carrying a potential 20-year prison sentence.

In April 2019, police carrying an Odebrecht-related arrest warrant arrived at the door of Humala’s predecessor, former two-term Peruvian President Alan Garcia. As they tried to arrest him, Garcia locked himself in a bedroom, pulled a gun and killed himself.

Prosecutors said the Odebrecht case was a landmark in the fight against public corruption in Latin America and globally.

Robert L. Capers, then the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York, said in a statement announcing the Odebrecht plea deal: “The message sent by this prosecution is that the United States, working with its law enforcement partners abroad, will not hesitate to hold responsible those corporations and individuals who seek to enrich themselves through the corruption of the legitimate functions of government, no matter how sophisticated the scheme.”

The fine print

But, it turns out, the sweeping deal with Brazil, U.S., and Switzerland had some significant limits.

Odebrecht, in fact, was not made to tell all. Its detailed statement of facts, for instance, discloses how much the company had paid overall in bribes across the region, but it doesn’t specify which projects were the subject of the payoffs or who had received them.

Prosecutors in other countries are working with Brazilian authorities to build their own cases and some have filed charges against politicians and others who have been implicated. in Odebrecht’s scheme. Odebrecht and its executives, meanwhile, are negotiating deals for immunity or leniency in exchange for cooperation. So far, agreements are in place in Peru, the Dominican Republic, Panama, Ecuador and Guatemala, along with Brazil, the U.S., and Switzerland.

One catch is that the countries must agree not to prosecute Odebrecht executives who already made plea deals with Brazil.

But much depends on whether governments have the resources to investigate and prosecute these crimes and, analysts say, whether they have the political will. Odebrecht’s bribery operation reached into the highest levels of politics and society across the region, and national responses have varied widely. For instance, over the last two years, Peruvian prosecutors have made 68 document requests of Brazilian authorities; Dominican prosecutors have made three.

The Dominican economist

Much remains to be discovered about the array of companies, consultation and service agreements, and secret bank accounts employed by Odebrecht’s bribery division.

But one thing is clear: The division’s Drousys files contain the names of prominent figures in positions of trust who have never been openly questioned about their relationships to Odebrecht — until now.

Andrés Dauhajre is a well-known member of the Dominican Republic’s political elite.

The bespectacled, silver-templed economist writes a weekly column in the newspaper El Caribe. He was part of a delegation of business leaders that accompanied Dominican President Danilo Medina on a state visit to China in November.

He also leads the Economy and Development Foundation, an economic consultancy, based in the Dominican capital of Santo Domingo, that often wins contracts from the state.

In late 2013, when the Dominican Republic’s state utility company was awarding a contract to build the Punta Catalina coal-fired power plant, a 770-megawatt facility on the Caribbean coast, it tapped Dauhajre’s consulting firm, along with two others, to evaluate the bidders’ financial proposals.

By then, the state utility had disqualified several bidders, citing poor technical proposals, and the only remaining candidate for the job was a consortium led by Odebrecht.

To win the contract, Odebrecht still needed to have its economic offer and financing plan approved. Dauhajre and the other consultants approved its plan, and Odebrecht was awarded a contract of more than $2 billion, hundreds of millions of dollars more than some of the bids by its sidelined competitors.

When the Odebrecht scandal exploded across Latin America, the company admitted to prosecutors in December 2016 that its corrupt payments included $92 million in bribes in the Dominican Republic. The Punta Catalina project immediately fell under suspicion.

A commission led by an influential clergyman, Monsignor Agripino Núñez Collado, was appointed to investigate the contract. Among the witnesses interviewed was Dauhajre.

On Feb. 5, 2017, three days after his testimony, Dauhajre indignantly dismissed suspicions that Odebrecht’s contract had been inflated.

“The supposed overvaluation of Punta Catalina is the best-marketed lie in the Dominican Republic in recent years,” Dauhajre wrote in his column in El Caribe, one of several pieces in which he publicly defended the power plant and its financing. These columns did not mention any financial relationship between himself and Odebrecht.

Ultimately, the commission found no proof of irregularities in the plant’s bidding or financing, handing a major victory to Odebrecht. The Dominican attorney general came to a similar conclusion upon announcing charges against 7 defendants in the Odebrecht case in June 2018, saying his team had thoroughly investigated Punta Catalina and found no evidence of corruption.

The ledgers of Odebrecht’s Structured Operations unit show dozens of payments that appear to have eluded investigators, who did not have access to the records obtained by ICIJ.

A spreadsheet tracking the unit’s hidden payments from December 2013 through December 2014 reveals 62 payments totaling more than $39 million related to a “Planta Termo,” or “Thermoelectric Plant.” Five of the payments, worth more than $3.3 million, were directed to a company listed at a Dominican address called Baker Street Financial Inc.

The spreadsheet indicates that at least two of the payments to Baker Street passed through a Bahamas-based company, Fincastle Enterprises Ltd., which has been cited by prosecutors in Peru as a vehicle for Odebrecht’s bribes. These payments were made in May and July 2014, several months after Odebrecht’s financial plan was approved.

On Dec. 7, 2015, Baker Street Financial paid more than $2 million for a 12th-floor apartment in a sleek glass-clad building in a posh midtown Manhattan neighborhood, around the block from Le Bernardin, the acclaimed French restaurant.

New York City records of the sale include a deed signed by Baker Street Financial’s sole director: Andrés Dauhajre.

Dauhajre told ICIJ that the payments he received from Odebrecht were for consulting services that he provided in connection to the financing of the power plant. Dauhajre said Odebrecht retained his services in early 2014 after one of the key funders expected to underwrite the project, the Export–Import Bank of the United States, pulled out due to a directive by then-U.S. President Obama not to finance coal-fired power plants due to their contributions to climate change.

Dauhajre said he helped Odebrecht find alternative sources of funding for the plant, and that Odebrecht had proposed Fincastle Enterprises as the vehicle for his payment.

“Baker Street Financial successfully and effectively provided the advisory service requested by Odebrecht during 2014 and 2015,” Dauhajre said in a letter to ICIJ. “It was this financial service that generated the remuneration.”

The cast grows larger

The files of the Structured Operations unit entangle public officials and prominent citizens who are connected for the first time to Odebrecht’s hidden payments.

One of those officials is Constantino Galarza Zaldivar, who in October was elected vice governor of Callao, an urban province that includes Peru’s leading port. A Panamanian company, CGZ Ingenieria Corp., received in late 2014 two payments totaling $240,000 related to a Peruvian gas pipeline, Drousys records show. Galarza, whose initials are CGZ, is the president and a director of CGZ Ingenieria, according to records from the Panamanian Corporate Registry.

Galarza also served as the company’s general manager for years, including at the time it received the payments, according to his LinkedIn page. CGZ Ingenieria offers support services in engineering, business intelligence, and legal, financial and institutional relations, and has offices in Lima, Panama, Colombia and Madrid, Galarza’s LinkedIn page states.

Galarza has not been linked previously to Odebrecht’s bribery unit. His name emerged in March in connection with another controversy. In an audio recording played on the Peruvian news program Panorama, Galarza appears to plot the assassination of his boss, the Callao governor, Dante Mandriotti.

In the recording, Galarza discusses plans for a hit on Mandriotti with an unknown associate, saying “a high-level professional from Mexico or Colombia” would be needed to do the job. “They need to put a lot of bullets in him,” Galarza says in the recording.

After the recording’s release, Mandriotti called on prosecutors to charge Galarza with attempted homicide, conspiracy and other offenses. Prosecutors in Callao indicated that they will investigate the matter.

In a news conference, Galarza admitted that his voice is heard in the recording, but he said he had spoken in a moment of anger with no intention of carrying out an assassination.

In an initial telephone conversation with an ICIJ journalist on June 21, Galarza denied any business dealings connected to Odebrecht or the Gasoducto Sur pipeline. Then, in an interview on June 24, Galarza said that his company was paid for financial consulting indirectly related to the pipeline. He said his firm was hired by an Indian construction company, ECI Engineering & Construction Company Ltd, that was working on a pipeline for liquids that would run parallel to the Gasoducto Sur. This second pipeline, Galarza said, was a private project also led by Odebrecht. He said his firm was not paid by Odebrecht directly, and that the parallel pipeline was not ultimately carried out.

In the interview, Galarza also cast doubts about the recording in which he discussed assassinating Mandriotti. He said that while some parts of the recording were authentic, he said that other sections of the recording were false and likely manipulated.

The Structured Operations Division’s reach extended across Latin America. The files show a payment of $200,000 in January 2014 to a Panamanian company called El Facilitador Holdings, related to a public works project referred to as “LE LM” in the unit’s files. It is unclear what “LE LM” is or what the payment was for.

The president and a director of El Facilitador is a Salvadoran radio executive, Jose Luis Saca. He has served since 2015 as the president of the International Association of Broadcasting, a group that represents some 17,000 radio and television broadcasters across the Americas.

Saca, who advises the United Nations on media issues in his capacity as the association’s president, travels Latin America advocating press freedom.

Saca did not respond to ICIJ’s inquiries, which included repeated emails, telephone calls and a letter to the International Association of Broadcasting, and a hand-delivered letter to Radio Corporación, the Salvadoran radio company where he serves as vice president.

Unrevealed projects

It was a Friday morning in the waiting room of the Dr. Robert Reid Cabral Children’s Hospital in Santo Domingo. About 50 people — mostly babies and other young children and their anxious parents — waited on rusted metal seats to see a doctor. The room was hot. The sound of children crying was constant, swelling and receding in different parts of the room.

Families like these, said Pimentel, of Participación Ciudadana, are the true victims of the kind of corruption practiced by Odebrecht. As governments squandered money on public contracts inflated by graft, vital public services were starved.

While it is not possible to attribute specific incidents to the effects of corruption, the dollar figures involved are massive and the stakes are high. For example, in 2014, the Structured Operations unit’s hidden payments may have helped the company win billions of dollars in contracts for the Punta Catalina power plant and other projects. In the same year, 11 children died at the children’s hospital because it ran out of oxygen. The hospital had fallen deeply in debt to oxygen suppliers.

“What is lost in corruption is that the Dominican state can’t invest in public policies that guarantee people’s rights,” Pimentel said.

The Dominican Republic is one of a half-dozen countries in which major infrastructure projects are tied for the first time to Odebrecht’s corruption.

A subway system for Quito — the high-altitude capital city that is home to more than 1.5 million people — was Odebrecht’s most important project in Ecuador. The project’s construction budget came in at just over $2 billion. The 14-mile system, slated to open in December, is expected eventually to transport as many as 530,000 commuters a day.

When Odebrecht’s international bribery was exposed, local prosecutors launched an investigation into whether the company’s work on the Quito Metro had been tainted by bribes. In March 2018, after more than a year on the case, prosecutors closed the investigation, saying there wasn’t evidence to support charges.

The files of the bribery division might reopen it.

In Drousys system emails, Odebrecht employees, code-named “Silver,” “Fred” and “Wilson,” discuss payments for the Quito Metro that were routed through their department. In July 2015, for instance, Silver asks Fred whether payment for the Metro had been issued and if it had been made via Meinl Bank, a bank whose Antigua branch was acquired by Odebrecht operatives in 2010 to facilitate corrupt payments, according to prosecutors. Fred replied in the affirmative.

“The Metro payment was also made through Meinl,” Fred wrote in an email to Silver.

The message notes that the payment was made through the company Fortress Investors Ltd., which appears repeatedly in the bribery division’s files as a conduit for payments. The records don’t say who received the secret payments or their purpose.

Mauricio Rodas, the former mayor of Quito whose administration approved Odebrecht’s contract, told an ICIJ journalist that Odebrecht was chosen solely because it offered the least expensive economic proposal, and that the project would reshape transportation in Quito.

The leaked Drousys files include other secret payments related to projects that so far have not been connected to the Odebrecht scandal. The Gasoducto Sur, a gas pipeline in southern Peru and the most prominent project of former Peruvian President Ollanta Humala’s administration, is mentioned in connection with 17 payments in 2014 totaling more than $3 million.

A Peruvian prosecutor indicted Humala and his wife, Nadine Heredia, in May for allegedly laundering assets provided by Odebrecht. Payments related to the $7 billion pipeline have not been disclosed by Odebrecht.

The Ruta Viva, a highway between Quito and Ecuador’s largest airport, is not mentioned in Ecuadorian prosecutors’ filings but is named in the new trove of documents in connection with a payment of 915,000 in an unspecified currency made in October 2012, several months after the city awarded Odebrecht the contract to build the road. The leaked documents don’t say who received the hidden payment.

In Panama, the country’s first ever rapid-transit system, in Panama City, and an expansion of the city’s airport, Tocumen International, are linked for the first time to millions of dollars in hidden payments made in 2014.

In Venezuela, new details emerged showing more than $34 million in secret payments in 2014 linked to Line 5 of the Caracas Metro, for which only one of 10 planned stations has been built.

It’s not clear why hidden payments found in Drousys documents have not come to light in public investigations. In response to ICIJ’s inquiries as to why it had not acted on the payments revealed in the Dominican Republic, the Dominican Attorney General’s office called on the consortium to turn over any documents relevant to Dominican investigations.

“It raises the interest of this law-enforcement body that a consortium of journalists has in its power information that is relevant to a criminal investigation,” anti-corruption prosecutor Laura Maria Guerrero wrote to ICIJ. “We order you to deposit to the Public Prosecutor’s Office any documents that support your statements.”

(ICIJ’s policy is not to collaborate or share materials with law enforcement agencies.)

Jessica Tillipman, an assistant dean at George Washington University Law School who specializes in government contracts and anti-corruption issues, said that the payments could be the subject of ongoing criminal probes or that Odebrecht might have argued successfully that the payments didn’t violate the law.

If Odebrecht, for whatever reason, withheld information about its crimes from authorities, the consequences could be dire. “If the government finds out after the fact, it could blow up the terms of the agreement,” Tillipman said.

Pimentel, the anti-corruption activist, said Dominican prosecutors’ failure to pursue wrongdoing in projects such as Punta Catalina represents a failure of political will in a country where political and economic elites are closely intertwined.

Citizens have long known that corruption and impunity were serious problems, Pimentel said, but the Odebrecht case has revealed that it reaches the highest levels of government. The meager results from official investigations, he said, demonstrate the government’s continuing inability to banish Odebrecht’s stain.

“The Odebrecht case,” he said, “has served to strip bare the Dominican Republic’s institutions.”

Contributors: Andersson Boscán, Mónica Velasquez, Alicia Ortega Hasbún, Romina Mella Pardo, Mónica Almeida, Emilia Diaz-Struck, Dean Starkman, Tom Stites, Joe Hillhouse, Richard H.P. Sia, Fergus Shiel, Margot Williams, Delphine Reuter, Mary Triny Zea, Joseph Poliszuk, Milagros Salazar, Gustavo Gorriti, Ben Wieder, Kevin Hall, Jimmy Alvarado, Nora Gámez-Torres, Amy Wilson-Chapman and Hamish Boland-Rudder.