In June 2014, Syria’s civil war was entering its bloodiest phase. Rebel militias had seized large swaths of the country. The Islamic State had set up a de facto capital in the city of Raqqa and would soon rampage across Syria and Iraq.

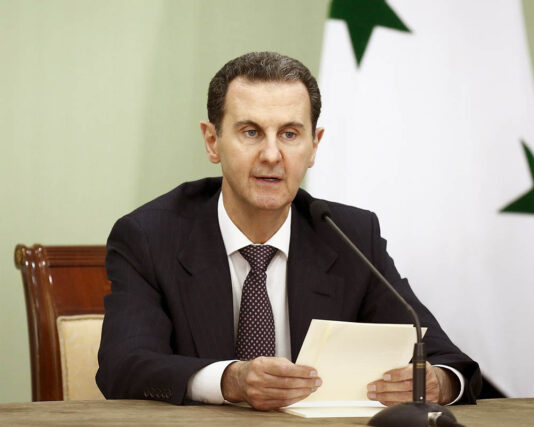

In Damascus, Syria’s capital, President Bashar Assad was running out of money and clinging to power through increasingly brutal means. His regime had launched sarin gas attacks on the city’s suburbs and was subjecting rebel-held areas to indiscriminate shelling and bombing.

That same month, an official for Syria’s state-owned oil company, Syrian Petroleum Co. (SPC), sent a terse request via fax to H.A. Cable Export Co. Ltd., an import-export firm registered in Cyprus.

The Syrian government wanted help buying drilling equipment — crucial to keep the regime’s oil revenue flowing — from an American oil equipment giant, NOV Inc.

The SPC official said he had received a letter from National Oilwell Varco (NOV’s name at the time) that referred all sales inquiries to H.A. Cable Export. The Cypriot firm, the official wrote, had been “authorized by National Oil Well Company to supply National Oil Well S/Ps [spare parts] of American Origin.”

Over the next five years — some of the most brutal of the civil war — the SPC and the Cyprus firm, working as a middleman, would discuss buying equipment from NOV.

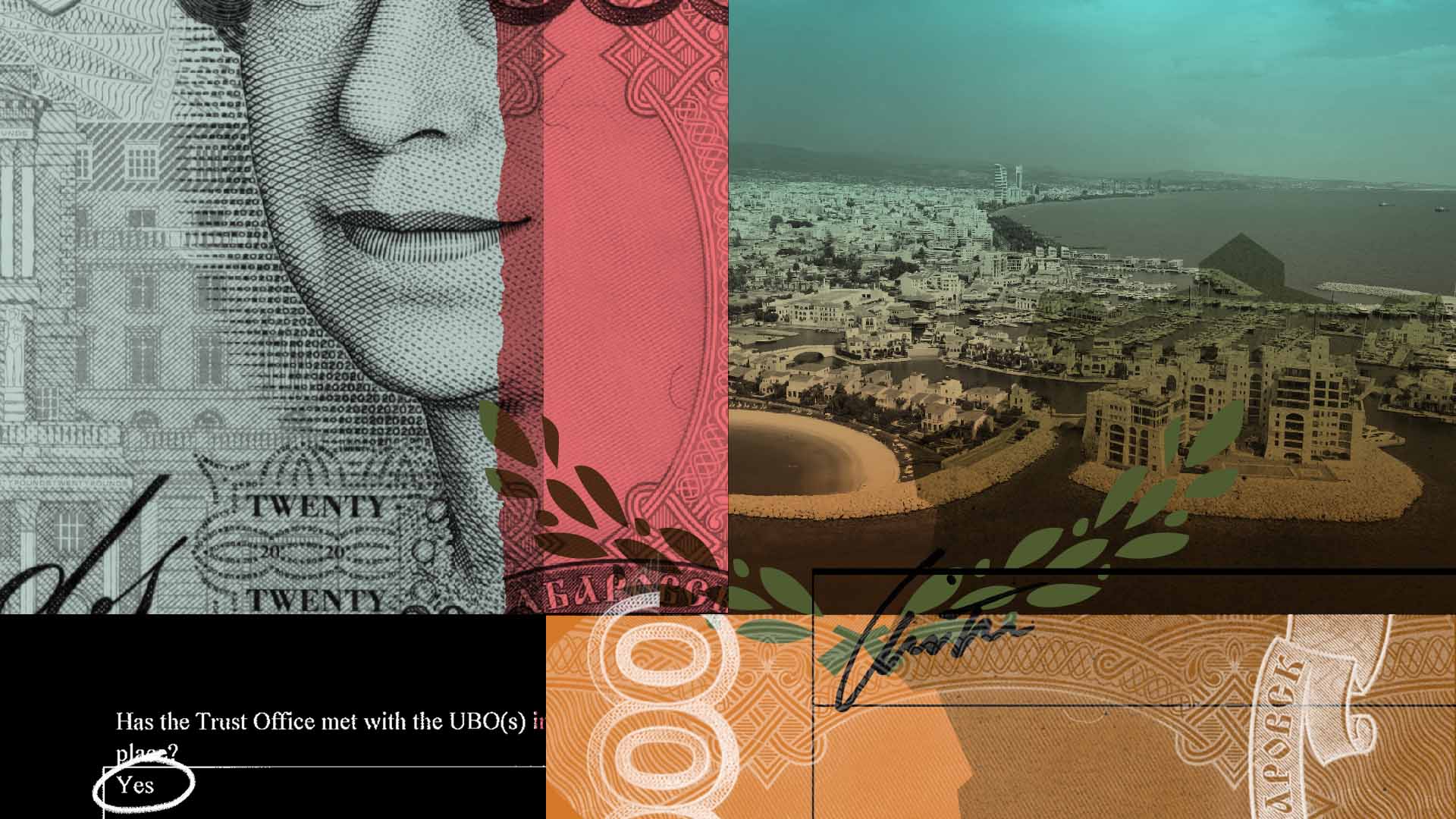

The correspondence involving the NOV equipment emerged from a review of data as part of Cyprus Confidential, an investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which brought together more than 60 media partners, including the Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism project and investigative news outlet Daraj. Based on leaked documents, including records from six Cyprus corporate services providers, the project shines a light on the island nation’s role in helping authoritarian actors evade Western law.

The 3.6 million leaked files at the heart of the Cyprus Confidential investigation come from six financial services providers and a website company.

The providers are: ConnectedSky, Cypcodirect, DJC Accountants, Kallias & Associates, MeritKapital, and MeritServus in Cyprus. The MeritServus and MeritKapital records were obtained by Distributed Denial of Secrets. Leaked records from Cypcodirect, ConnectedSky and i-Cyprus were obtained by Paper Trail Media. In the case of Kallias & Associates, the documents were obtained from Distributed Denial of Secrets, which shared them with Paper Trail Media and ICIJ. DJC Accountants’ records were obtained by Distributed Denial of Secrets and shared by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. The partner organizations shared all the leaked records in the project with ICIJ, which structured, stored and translated them from several languages before sharing them with journalists from around the world. Additional records came from Latvia-based Dataset SIA, which maintains the i-Cyprus website, through which it sells information about Cyprus companies, including Cyprus corporate registry documents.

The correspondence between the SPC and H.A. Cable Export had been obtained from the Cyprus law firm Demetrios A. Demetriades LLC, also known as Dadlaw, one of 14 additional offshore services providers whose leaked documents formed the basis of ICIJ’s 2021 Pandora Papers investigation. H.A. Cable Export was a Dadlaw client.

The Dadlaw records contain confidential communications that discuss five separate transactions to provide American drilling equipment to the Syrian firm between 2014 and 2019 in violation of U.S. sanctions. Assad’s government was an international pariah throughout this period: The United States had prohibited the export of any goods or services to Syria’s oil industry since 2011. NOV, which admitted in 2016 to sanctions violations involving deals with Iran, Sudan and Cuba, had declared to U.S. authorities that it ceased all business with Syria before 2014.

But while NOV publicly claimed to be following U.S. law, the documents show Syrian officials seeking to buy NOV equipment through the Cypriot import-export firm in order to evade sanctions.

In a June 2016 fax to H.A. Cable Export, for instance, the officials write that a transaction to purchase drilling equipment had been “turned to yr. company due to USA sanction imposed on Syria.”

The leaked documents, which don’t say if the discussed transactions were completed, consist of scanned digital copies of faxed correspondence between the SPC and H.A. Cable Export, which was owned by a Damascus-based businessman.

These documents raise questions about why the SPC, a sanctioned Syrian company, would claim that NOV directed it to a middleman to purchase NOV equipment; whether the American firm actually sold the gear to the middleman; and, if so, whether it was aware that the middleman was buying it on behalf of the sanctioned Syrian firm.

If, in fact, the SPC did buy the equipment through a middleman, any such purchases would violate U.S. and EU sanctions. They would also have come at the expense of Syrian lives, providing the Syrian regime with the means to conduct its vicious crackdown.

NOV Inc.’s chief compliance officer, Brent Benoit, told ICIJ in an email that the company reviewed its transactions and found no evidence that NOV was involved in any sales to H.A. Cable Export during the period in which the discussions between H.A. Cable and the SPC occurred. He did not address a question about the letter the SPC said in June 2014 it had received from NOV referring it to H.A. Cable Export.

Benoit said that while NOV identifies the end user of its goods for each sale, such equipment can be resold over time. He said that the equipment described in the leaked faxes could refer to secondhand or even counterfeit goods. “What we can tell you is that we have no record of [the equipment] coming directly from us to anyone in Syria or to HA Cable Export Company,” he wrote.

Oil and the Assad Regime

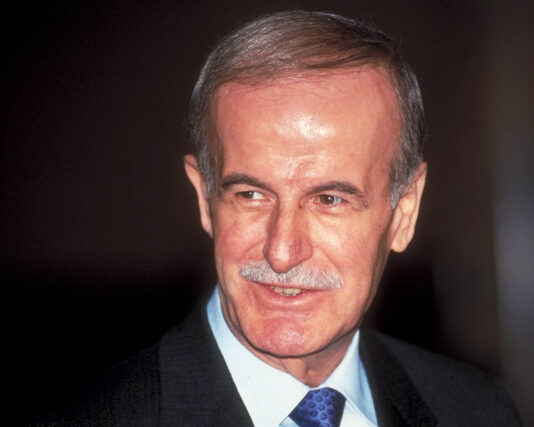

The Assad family has ruled Syria since Bashar Assad’s father, Hafez, seized power in a coup in 1970. In 1979, Syria became one of the first countries designated by the U.S. State Department as a state sponsor of terrorism and was placed under U.S. sanctions, which have escalated over the years. The civil war began in March 2011 with nonviolent protests against the younger Assad’s rule and gradually transformed into an armed uprising that saw parts of the country fall from government control.

In August 2011, as part of a sweeping sanctions package, President Barack Obama signed an executive order singling out the SPC. While U.S. energy firms had conducted some business in Syria before that date, the new sanctions rendered any commercial relationship with the Syrian oil industry illegal. That same year, the European Union also imposed stringent sanctions on the Syrian oil industry.

As the SPC struggled to maintain production in the fields still under regime control, Syrian oil and gas revenues — which made up 25% of the state budget before the war — dropped sharply. Syria’s currency plunged from roughly 50 Syrian pounds to the dollar to more than 13,000 pounds today, while 90% of the population fell below the poverty line. Given the collapse of the Syrian economy and the devaluation of its currency, revenue from oil and gas — which generates U.S. dollars — was vital to regime finances.

Any drilling equipment therefore represented a lifeline for the regime.

Ayman Asfari, a Syrian-born former oil executive and founder of an opposition-aligned organization supporting Syrian civil society, told ICIJ that the oil revenue flowed directly to the Assad family, as well as an elite army unit led by the president’s brother and pro-Assad militias.

“It was very important,” Asfari says. “The regime managed to circumvent sanctions to keep the oil flowing through third parties.”

A Global Player

NOV grew out of a drilling and equipment maker founded in 1862, and the firm has expanded through acquisitions ever since. The Houston-based company went public in 1996 and in the past two decades has been on a buying spree, completing dozens of acquisitions to become a global player alongside larger rivals Halliburton and Baker Hughes. It now has operations in more than 550 locations across the world, according to its annual report, and more than 250 subsidiaries.

Its reach has also brought it to conflict zones around the globe, including in Syria before the civil war and the imposition of the strictest U.S. sanctions. The leaked documents include a 2008 invoice from H.A. Cable Export, billing the SPC roughly $450,000 for NOV-manufactured equipment: spare parts for drilling rigs.

After NOV issued its 2011 annual report, it disclosed to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission that it had conducted legal business in Syria prior to that year and for a short period after the imposition of more-stringent U.S. sanctions. The company said it was “winding down” its business in Syria and had applied to the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control for a license to collect roughly $141,000 owed to it by a Syrian client.

Benoit, NOV’s chief compliance officer, told ICIJ that his department’s review had not been able to identify the NOV subsidiary involved in the transactions under the waiver.

NOV later declared to the SEC that, since 2014, neither it nor its subsidiaries had made any sales to Syria. “[T]he Company completed its winding down process and its sales directed into Syria are zero,” its general counsel wrote in 2017.

But the leaked documents raise questions about the company’s declaration. The Syrian national oil company told H.A. Cable Export in the June 2014 fax that it had received the letter from NOV asking it to go through the Cyprus firm. And three months later, the SPC’s top official, General Director Omar al-Hamad, followed up on the potential sale, asking H.A. Cable Export’s lawyer for a final invoice for two shipments.

Al-Hamad told ICIJ in an email that H.A. Cable Export never completed the sales and that the company’s lawyer told him that the import-export firm couldn’t procure the equipment due to U.S. sanctions. He said that H.A. Cable had not supplied any material to the SPC since 2008 — the year it billed the state-owned company for NOV-manufactured parts for drilling rigs.

The SPC again contacted H.A. Cable Export in the June 2016 fax that said it wanted to conduct the purchase through the Cyprus firm “due to USA sanction.” The note refers to a deal for drilling equipment it had already “concluded with ‘Oilwell – U.S.A.,’” an apparent reference to NOV.

In that 2016 fax, al-Hamad’s successor as SPC general director, Trad al-Salem, told H.A. Cable Export that a letter of credit had been opened at the Central Bank of Syria to pay for the purchase of spare parts for so-called drawworks used to raise and lower equipment into and out of the drilled hole. He said the letter of credit had been extended until late July — meaning that the transaction needed to be completed seven weeks from the date of al-Salem’s fax.

The same year, NOV paid $25 million to settle allegations it had violated U.S. sanctions on Iran, Sudan and Cuba in a case involving sales to those countries between 2002 and 2009. In that case, the Treasury Department found that a NOV subsidiary had exported equipment to Iran through an intermediary and wrote in its enforcement action that senior executives had “willfully blinded” themselves to their subsidiary’s “deliberate non-identification of Iran” as the end user of the equipment.

The regime managed to circumvent sanctions to keep the oil flowing through third parties.

— Ayman Asfari, a Syrian-born former oil executive

Byron McKinney, the director of trade finance and compliance solutions at S&P Global Market Intelligence, told ICIJ that sanctioned entities often use front companies connected to them to evade sanctions. “In certain occasions more than one front is used to further mask the real end user of the goods,” he says. “With the masking of the ‘real’ individuals [involved in the transaction], U.S. services and financial institutions can be used to facilitate the movement of goods and funds.”

That may be the role played by H.A. Cable Export, which was owned by Ahmad Hadaya, a Damascus businessman who was born into a prominent family best known for selling imported Suzuki and Isuzu cars in Syria. Hadaya incorporated H.A. Cable Export Co. Ltd. in Cyprus in 1989, and the firm at first shipped a wide variety of goods to Syria before turning in the mid-2000s to equipment and chemicals used in drilling.

In response to questions from ICIJ, Hadaya’s lawyer wrote that Hadaya “has no comments on the transactions you have questioned other than to indicate that no purchases were made from National Oilwell/Varco and no shipments were made to Syrian Petroleum Company. The project never took place and was not completed.”

According to two Syrian businessmen who spoke to ICIJ and its media partner SIRAJ on the condition of anonymity, Hadaya became involved in the oil industry through his involvement with Mazen Kanama, a Syrian businessman who operates a large oil services company in the eastern province of Deir Ezzor, home to most of Syria’s oil resources. A former manager of an oil company in Syria, also speaking on the condition of anonymity, told ICIJ that regime-connected businessmen were managing the oil sector on behalf of Assad, including operating companies in neighboring countries to import equipment.

The leaked records show H.A. Cable Export’s discussions with the SPC about NOV purchases continued until at least 2019. In January of that year, the SPC and the Cypriot middleman tried to buy spare parts for NOV pumps and drawworks. In a fax, the SPC told H.A. Cable Export to supply the materials “as soon as possible,” giving it 10 months to deliver them.

By then, Assad’s fortunes had improved dramatically. With the help of Russia and Iran, the Syrian regime had won key military victories across the country and received a diplomatic boost the month prior when the United Arab Emirates reopened its embassy in Damascus. Oil revenue made possible through the purchase of drilling equipment had helped pull the regime through.

By 2019, Hadaya’s lawyers seemingly lost contact with him: That year, one of Dadlaw’s attorneys submitted a sworn affidavit to a Cyprus court saying that H.A. Cable was ignoring her requests to resign as its secretary. According to Cyprus’ corporate records, H.A. Cable Export was dissolved in 2020.

Contributor: Mohammad Bassiki (SIRAJ)