“The patient XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX …

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXThe lead was discarded after explant, so was unable to be analyzed by the manufacturer.”

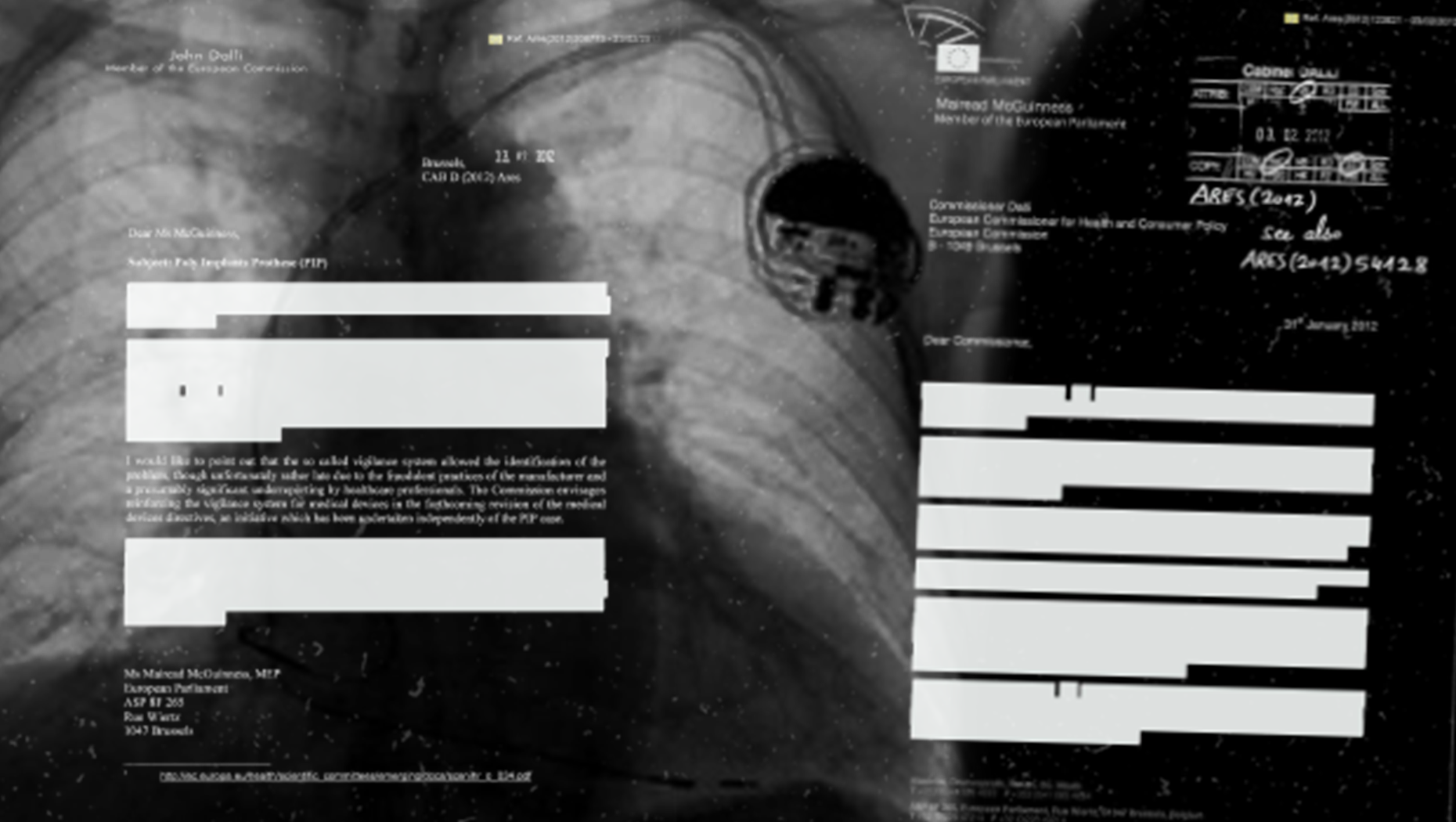

A glitch in this article? No. An example of what the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its partners in the Implant Files investigation received when they asked for public information on faulty medical devices.

This one from the Netherlands was typical in its redaction (or blacking out) of information that might have been more specific and revealing.

More than 250 reporters from 36 countries participated in the global investigation led and reported on by ICIJ. Over the course of the nearly year-long probe, they filed more than 1,500 requests for public records in their countries. But not even half were successful. In one that was strikingly not, Mexican reporters submitted 964 requests to federal agencies that produced only 44 responses.

Across the world, public bodies in charge of monitoring and regulating the medical device industry, as well as of keeping track of incidents caused by the devices, have fully or partly denied journalists’ requests for public records for a variety of reasons.

Among the rationales for rejecting requests or redacting documents: classified information or absence of data in Mexico and France; a year-long backlog of requests in the U.S.; lack of staff who can redact sensitive details in Belgium; trade secrets in Japan, Europe, the U.K. and many other countries.

Disclosure and public scrutiny are very important in finding what is wrong in our community

When reporters did get data on incident reports, it wasn’t always in a format that could be used to do trend analysis or advance any reporting leads.

In France, the list of incidents associated with medical devices that was provided by health authorities looked like “a spreadsheet filled by an intern,” said Le Monde’s Stéphane Horel. The file didn’t include any information on incident outcomes, such as deaths or injuries, and had many empty rows, she said. “That’s how we realized the system is broken.”

If authorities can’t keep track of possibly harmful incidents, who can?

In Canada, it took two years for David McKie, a data journalist with Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, to obtain adverse event data from the national regulatory agency.

The breakthrough came last summer when a frustrated McKie decided to apply a strategy basketball players use when a victory is uncertain. “I exercised a ‘full-court press’ where you pull out all the stops in order to achieve success,” McKie said. “I complained and inundated [the agency] with requests. I became one of their bigger problems.”

Just a few months before publication, his efforts were successful. CBC obtained a copy of Canada’s medical device adverse event data since 1977, which went on to become the “heart” of the reporting team’s investigation.

“The database gave us an unprecedented window into the medical device regulatory process,” McKie said. It also “highlights that lack of transparency is at the heart of the system.”

CBC created Canada’s first medical device incident database and made it available for the public on its website. ICIJ created another database, also from public records. The International Medical Devices Database permits users to explore more than 70,000 recalls, safety alerts and field safety notices in 11 countries. Users can search by device name, by manufacturer, or by country, and the database will grow as ICIJ acquires and records more information.

More than one hundred countries around the world have legislation on freedom of information, but its application “leaves a lot to be desired,” said Toby Mendel, director of Halifax-based Centre for Law and Democracy and specialized in freedom of expression law.

Some reporters also fear that corporations’ concerns tend to prevail even when public health is at stake.

Jet Schouten, a reporter with Dutch TV show Radar, who has been covering safety issues tied to medical devices for years, said she was “flabbergasted” when her country’s authorities explained the reason they weren’t publishing all the adverse event reports they receive.

Their response to Schouten and the daily Trouw put it simply: “The relationship between the inspectorate and manufacturers of medical devices, which is indispensable for the effective monitoring of the profession, will be disproportionately damaged by the disclosure of medical data.”

“It’s a system based on fear,” Schouten said. Regulators “listen to the industry and not to patient safety.”

A week after publication, in countries such as France, Spain and Japan, ICIJ’s media partners’ fight — and long wait — for open records continues.

“Disclosure and public scrutiny are very important in finding what is wrong in our community,” said Yasuomi Sawa, a reporter with Japanese news agency Kyodo, who is still waiting for a response to his team’s 76 requests. Just because the government has information on medical device safety it doesn’t mean the public is safe, he said.

Read (some of) the FOIA responses ICIJ and partners received

The Netherlands

- Manufacturers Incident Report

- FOIA Response, The Netherlands – Ministerie van Volksgezondheid Wlzijn en Sport

Mexico

France

- Team NB- EC on Notified Bodies – 2012

- EC document on Notified Bodies – 2012

- EC “revision of MD legislation” – 2012

- Draft report of EP on MD regulation – 2013

- EC Medtech Europe – 2013

- Eucomed – 24 Ares(2013)3050282

- EC Mimica’s Hearing in the EP – 2018

- France NCARs 2012 2018

ICIJ

- European Commission’s rejection letter

- Medtronic FDA Inspection Document – 2013

- Baxter Auto Syringe AS50A 501(k) Review – 1994

- Response – Infusion Systems LLC Request for Summary of Safety and Effectiveness – 2010

- Infusion Systems LLC Request for Summary of Safety and Effectiveness – 2008

- FDA Response – University of Washington request for Medtronic SynchroMed research and studies – 2008

- University of Washington FDA request for Medtronic SynchroMed research and studies – 2005

- Medtronic SynchroMed Recall Action Memo

- Covidien pension complaint

- Codman Infusion Pump FDA Summary of Safety and Effectiveness – 1991

- Medtronic SynchroMed Summary of Safety and Effectiveness – 1988

- Medtronic SynchroMed Intraspinal Morphine Supplement – 1991

- Medtronic FDA Inspection Document – 2013

- Medtronic Parmadigm Complaint – 2016

- Dexcom Consumer Fraud Complaint – 2008

- Recall recommendation review SynchroMed – 2018

- CDRH’s Health Hazard Evaluation SynchroMed II – 2011SynchroMed II – 2011