Cobblestone walkways line the quiet canals of Sète, a French community of 40,000 nestled along the Mediterranean about 85 miles west of Marseille. It is a picturesque place, bounded on one side by Mount Saint Clair and the other by the clear turquoise water of the sea. But there is more to this seemingly sleepy tourist town.

Anchored in the harbor are dozens of multimillion-euro fishing boats — vessels that comprise the world’s most productive tuna fishing fleet, with 36 vessels targeting the prized, and increasingly at risk, Eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna. Fed by ravenous demand in Japan, Mediterranean fishing fleets — led by those in Sète — have fished out as much as 75 percent of the Eastern Atlantic bluefin. Half of the stock, say scientists, has disappeared during the past decade.

If there is a ground zero in the controversial trade in bluefin, it is here in Sète. The port’s captains are steeped in generations of bluefin fishing — a regional vocation that predates the time of Christ. Their great-grandfathers emigrated from southwestern Italy — most from the same fishing village of Cetara on the Tyrrhenian Sea. As bluefin grew in popularity and price, the captains of Sète topped the hierarchy — the richest, most well-connected fishermen in France.

But Sète’s fishermen suddenly find themselves under unaccustomed scrutiny. So decimated are stocks of bluefin that regulators are considering a moratorium. Prosecutors are dissecting captains’ records, looking for evidence of fraud and fishing beyond legal quotas. Even their biggest buyers in Japan are starting to verify the source of the bluefin they’ve bought for years with no questions asked. “Everyone cheated,” acknowledged Roger Del Ponte, one of the bluefin captains under investigation who denied the charges pending against him. “There were rules but we didn’t follow them.”

The captains of Sète are not alone. For more than a decade, southern Europe’s fishermen went on a feeding frenzy with help from an emerging cast of North African and Turkish affiliates. Widespread fraud and a lack of official oversight have fueled a massive black market, in which, at its peak, between 1998 and 2007, more than one in three bluefin was caught off-the-books, according to an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Through dozens of interviews with fishermen, divers, ranchers, enforcement agents and ministry officials, plus additional information gleaned from inspection reports, internal regulatory data and court files, ICIJ’s reporting shows a decades-long system of deceit, lack of oversight, and outright fraud. There is plenty of blame to go around. The illegal and negligent activity extends across the supply chain, ICIJ found, from fleets, through ministry offices, to boardrooms in Japan, which buys 80 percent of the Mediterranean’s bluefin tuna.

Officials looked the other way while fishermen violated official quotas at will and engaged in questionable practices that included misreporting catch size, piloting illegal spotter planes, catching undersized fish, and plundering tuna from North African waters where international inspectors are refused entry. An illicit market even arose in trading quotas — when regulators finally started enforcing the rules — in which one vessel sells its nation’s quota to a vessel that had overfished.

The size of this black market in bluefin is enormous. ICIJ ran an analysis of the illegal and unreported trade, based on scientists’ estimated catches, Japanese market prices, and official quotas (the limits issued to countries on how many tuna they can catch). Our findings: between 1998 and 2007, the off-the-books trade generated an estimated $4 billion in revenue.

An unaccountable industry

Concern over huge catches of bluefin led to discussion in 1992 about including the fish alongside pandas on the list of endangered species banned to international trade. Officials skirted the threat, and later introduced national quotas. Responsibility for enforcement lay with the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), a Madrid-based regulatory body, and with its 47 member states and the EU. But ICCAT members voted for high quotas that its own scientists warned were unsustainable,and failed even to enforce those, industry and official sources say. Meanwhile, fleets of increasingly powerful, government-subsidized vessels have for more than a decade scooped up between 50,000 and 60,000 metric tons annually — nearly twice as much tuna as ICCAT quotas allowed, and three times what scientists in recent years deemed sustainable.

Years of mismanagement led independent auditors of ICCAT in 2008 to condemn its member countries for having “failed to abide by their legal obligations…failed to conserve bluefin tuna and failed in the eyes of the international community.” But their dramatic call for the immediate closure of bluefin fishing and ranching was ignored.

Through government subsidies, French fishermen built up the Mediterranean’s most powerful fleet of purse seine vessels, which use an efficient method of bluefin fishing with nets that close from below like a draw-string purse. Along with Spain and Italy, the three countries cornered the lion’s share of quotas. Greece, Malta, and Cyprus also fished under EU quotas, bringing the EU total to more than 130 purse seiners. Turkey, operating outside the EU, ran a dilapidated fleet of another 56 purse seiners, while Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia sold EU fleets entrance into their rich unregulated waters in exchange for a cut of the catch.

To account for their fleet’s massive overcatch, until 2007 French officials in Paris at season’s end adjusted the actual catch downward when they reported to the European Commission, which in turn reported to ICCAT, according to industry and government officials. The Italian and Spanish fleets also violated their quotas with impunity. “Within the bluefin fishery, all the countries were lying, it wasn’t just France,” ICCAT scientist Jean-Marc Fromentin said. “It was everybody. The only country to give their real figures would get fined, so in that kind of game, everyone lies.

“The officials didn’t respect the quotas, they didn’t control it,” Fromentin went on. “And at the same time, they authorized new boats to be built. So capacity increased. After a few years, the situation became really critical and we started talking about a risk of collapse.”

Set up to fail

For decades, the market for bluefin remained modest and largely regional — in fact bluefin was used in the United States largely for cat food. All that changed in the 1980s, as Japanese demand for fatty toro tuna exploded and sea ranches — large coastal pens for fattening the fish — began to provide a steady year-round supply. Manuel Balfegó, a Spanish fisherman and rancher, recalled the acceleration of his craft in the ‘80s when Japanese and Koreans vessels discovered the rich bluefin fishery in the Balearic Sea off Spain’s eastern coast, where he now ranches tuna for Japanese buyers. “There were so many fish, no one knew what to do with them all,” he said. One tuna trader recalls those golden years in the early 2000s buying fish off the Spanish coast. By strategically stacking the tuna, they could fit 50 into a single freighter truck.

The booming export market combined with government subsidies by the EU and its member states — €26.5 million to vessels in Sète alone — to spur the renovation and expansion of Europe’s bluefin fleet. By 1998, the average French purse seiner was twice as long and four times as powerful as in 1970. By 2008, the EU fleet bloated under the capacity of 131 purse seine vessels. Another 500 such ships outside the EU — sailing under other ICCAT member flags — were registered to catch bluefin. One of the most successful fishing masters said a vessel needed to catch 250 metric tons of bluefin a year to make a profit.

With too few controls and too many ships, the bluefin hunters fished with abandon. ICCAT records show member countries caught about 30,000 tons of bluefin in 1991 — the equivalent weight of three Eiffel Towers. Five years, later that figure topped 50,000 tons — a level that continued through 2007 — three times what ICCAT’s own scientists said was sustainable.

ICCAT instituted the first quotas in 1998, just as Spanish and Croatian fishmongers were revolutionizing the industry with “tuna ranches” in the Mediterranean. Instead of fishing small bluefin close to shore, killing them immediately and returning to port, vessels transferred live fish from their nets into cages, and then slowly towed the bluefin away to be fattened. Ranching allowed vessels to fish farther from port without fear their catch would rot. The deeper the waters, the bigger the fish. And Japanese buyers loved big tuna. Because operations are largely underwater, ranching made it nearly impossible to verify the size or number of fish caught, or how much they weighed. The advent of the ranches, coupled with widespread lack of enforcement, facilitated a decade that fishermen refer to as “the Jungle” — a Wild West in which bootlegged bluefin became business as usual.

The Jungle: 1998-2007

“We always fished more than the quota. No one told us to stop.”

The techniques fishermen used to increase their catch — and profit margins — were described to ICIJ by a dozen veteran bluefin fishermen. Fleets openly fished illegally undersized tuna, used banned spotter planes to search for spawning schools, and transferred tuna onto refrigerated vessels slated for Japan without declaring the catch. If a company was taken to task, the fine in the European Union averaged a mere 1/2,000 of the profits, according to an EU auditor’s report.

“We always fished more than the quota,” explained French Captain Vincent Caci, who gave up fishing this year because of growing restrictions on the trade. “It was normal. No one told us to stop. And France helped us build expensive new boats.”

In neighboring Spain and Italy, fishermen also encountered a similar lack of oversight.

“The fishermen were like guerrillas,” said Spanish fishing master Balfegó. “There were no individual quotas, only country quotas. So we fished, and we declared. The one to blame for the overfishing in the end was the country.”

In 2004, Nicolas Giordano, a fourth generation fishing captain from one of the most prominent bluefin fishing families in France, caught 1,200 tons of bluefin on his own. “Everyone fished as much as they wanted,” he said. “Until 2006 we declared what we wanted to declare. And the government said, ‘Okay.’ The administration didn’t do its job, and at the time no one took it seriously.”

By 2006, environmental groups had succeeded in drawing attention to the plight of the plundered tuna. Under growing public pressure, ICCAT that year launched a 15-year plan to rebuild stock by reducing quotas and increasing the minimum catch size. But the limits outlined were still twice as high as ICCAT’s own scientists recommended.

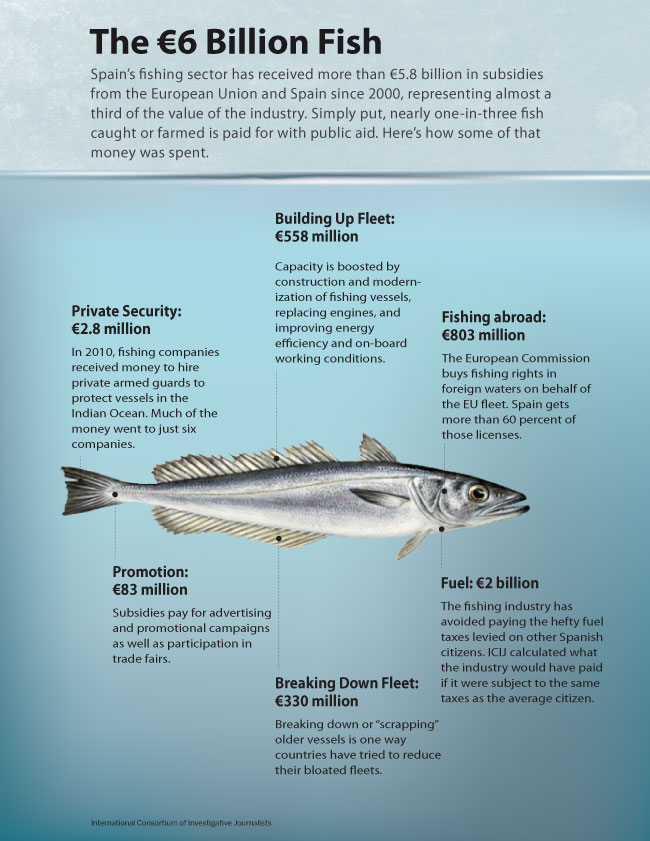

Ironically, subsidies continued to pour into the EU fishing industry at a rate of more than €800 million per year, with more vessels looking for fewer fish. Between 2005 and 2007 alone, the European purse seine fleet doubled in size.

In spite of its shortcomings, the ICCAT recovery effort carried political pressure to enforce the rules. But as the industry finally drew scrutiny, fishermen and ranchers colluded more closely to launder their wares, industry sources say. Patrick Mameaux, a longtime diver aboard French vessels, whose job it was to count the fish, recalls once fighting over figures with another diver who declared only half of the 80 tons of fish caught. Such tricks became commonplace. Mameaux said often divers would allow fish to pass undetected by stopping their videotape during the transfer from net to cage — an ICCAT requirement to confirm catch size. A prominent French fishing captain said an easier way was to carry a copy from an earlier — and smaller — catch. The diver would feign recording but turn in the pre-recorded tape.

As threats of enforcement mounted, fishermen say, French vessels took in extra cash selling their portion of the national quota in Malta and in Turkey, a country with a big but decrepit fleet and a disproportionally paltry quota. The scam, termed “paper quotas” proved especially helpful for captains who failed to catch enough fish during the season. Paper quotas work two ways. One vessel can “sell” its quota directly to another vessel, taking credit for fish actually caught by another nation’s vessel. Or, a vessel can sell its overcatch to a ranch, which finds a second vessel that is below quota to declare those fish — for a price.

Matters reached a head in 2007, when France — whose official quota that year was about 5,500 metric tons — declared nearly 10,000. The blatant disregard of the quota, combined with growing reports warning of a possible collapse of Atlantic bluefin stock, prompted French authorities to open a criminal investigation. It is the first time, say French officials, that the industry has been put on trial.

The Montpellier case

Fifteen miles from Sète, in the regional capital of Montpellier, a legal drama is playing out that has shaken France’s bluefin tuna industry. Under investigation are six of that nation’s most prominent bluefin fishermen, whom prosecutors suspect of failing to declare their full catches and selling their quotas to foreign vessels that had overfished their own quotas.

Two cases are working their way through the French legal system — one from 2007, another from 2008 — and they remain in a stage of secret pre-trial investigations. The cases, however, can be described from interviews with government sources, prosecutors, and fishermen who say they are the targets of the probe.

To prosecutors, the cases offer a rare window into how fraud infected the very heart of the bluefin industry. “From the moment a person commits fraud, when he fills out false documents, then there is absolutely no way to control the fishery,” said French prosecutor Patrick Desjardin, who recently took over the investigation. After three months of digging through sales records, tax documents and catch declarations in 2008, investigators identified nearly a dozen potential defendants. More than two years later, only six have been formally charged, although Desjardin said he has recently asked that the judge file charges against at least three other men.

While the potential punishment could reap prison time, the defendants will likely receive no more than a fine, Desjardin said.

In interviews the fishermen argue that the practices were so widespread — and enforcement so lax — that to single them out is unfair. “It’s like driving down the road,” said Del Ponte, one of the defendants. “If I know there are no police, I’m going to speed … They didn’t care, then all of a sudden, Boom!”

“Enforcement went from zero to 150,” said André Fortassier, another defendant, who denies he failed to report some of his catch in 2007.

src=”https://www.icij.org/sites/icij/files/projects/avollonecovessels.jpg” alt=”Avallone company fishing vessels in Sete” title=”Avallone company fishing vessels in Sete, France, docked alongside their partner vessels from Libya. Photo: Kate Willson” width=”380″ height=”285″ style=”float: right; margin: 10px;” class=”caption”>One of the defendants, Généreux Avallone, is the son of Jean-Marie Avallone, widely reputed to be France’s most powerful, well-connected fisherman. Prosecutor Desjardin said he has asked the judge to consider charging three others from Avallone’s company.

The company’s spokesman, Joseph Salou, vehemently denied that the company knowingly broke the law and said he is unaware of anyone other than Généreux being investigated.

“If the ministry had done its work, we wouldn’t be in this situation.”

The fishermen enjoy the sympathy of officials familiar with France’s laissez faire enforcement. “The fishermen aren’t as much to blame as the ministry,” said one source close to the investigation, referring to the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries in Paris. “They just profited from the system. The ministry let them do it. If the ministry had done its work, we wouldn’t be in this situation.”

Interviews with past and present French officials, as well as industry sources, indeed suggest a wide-ranging lack of accountability.

For years, for example, the Sète Office of Maritime Affairs gathered catch declarations when fishermen came to port — but did nothing with them. “There was simply no requirement to send along the information to Paris,” said one ministry official with close knowledge of the events. “So [they] collected the declarations but never did anything with them. Never calculated the catches.”

Scientists declared the French catch figures to the European Commission in those first years. But when France was criticized for overfishing, the Fishing Ministry demanded it be the office to report official figures. An ICCAT official recalled the occasion. “They got called out as the bad guy, but everyone was cheating,” he said. “France was just the only one to be open about it. So they did like everyone else and in the coming years, they cheated too.”

Joseph Salou, who represented the bluefin industry for years before going to work for the Avallone group, recalled when France declared overfishing its quota in late 1990s. “I can’t tell you the criticism we suffered,” he said. “We were denounced by the Spanish and the Italians, who cheated even more than we did.”

Over the years, the ministry’s director of Marine Fisheries in Paris was in constant contact with industry representatives, Salou explained. After each season, the industry and officials discussed catch data, and settled on an official figure. “It was a collaboration,” said Salou, who participated in the talks. “It was a discussion we had every year, the administration and the industry, because the administration was also complicit … The final decision was made by the director of fisheries, who said, ‘Okay, we’ll declare this number.’”

In France, responsibility for the bluefin industry ultimately leads to the Ministry of Agriculture and Fishing in Paris, under which the Department of Marine Fisheries operated. The Ministry, however, appears most reluctant to answer allegations that its officials doctored catch data — data that were then passed on to the European Commission and ICCAT. Ministry officials have not responded to a dozen written requests and numerous telephone calls from ICIJ requesting interviews or comment. Two former directors and a former minister also have declined to comment.

Jean-Marie Aurand was the Marine Fisheries director in charge in 1999 when his office took over reporting final catch figures to the European Commission. Today Aurand is the Ministry’s secretary general, one of its highest-ranking officials. He did not respond to multiple requests for interview or comment.

One official familiar with the annual discussions said it would have been difficult to believe that the Ministry’s director of fishing — and his superiors — did not know the situation. “They would have had to be deaf and blind,” he said. “There was a need to keep an important economic sector alive. There was also a need for the authorities not to risk being sanctioned by the European Commission.”

Knowledge of such blatant violations of overfishing, the source added, would also have been hard to miss by officials at the European Commission, who forward the final EU catch figure to ICCAT. “The Commission isn’t deaf,” he said. “By comparing the data, they could see the discrepancies between reported and actual catches. And people talked, so we knew when a season was lucrative.”

In a show of apparent outrage at the 2007 overfishing, the French Fishing Ministry demanded an investigation. After three months, investigators submitted a report detailing allegations of illegal acts by the country’s biggest bluefin fishing companies. The report also requested authority to investigate official complicity in allowing the overfishing to go on for so long, said a government source close to the investigation.

One ministry official involved with the catch data said he expected investigators to knock on his door and demand to know why he and others had done nothing to stem the illegal overfishing. “People at the ministry at the time knew that if the police did their job, sooner or later they would be asking about the government’s role,” he said.

But that visit never came.

A lack of enforcement

International condemnation of France’s role in plundering bluefin spurred the EU fisheries regulators to snap to attention. But fishermen were slow to believe the rhetoric about a crackdown.

“No one thought we were really going to have to respect the quota,” French fisherman Nicolas Giordano said. “They said, ‘We’ll fish what we want and we’ll see what happens.’”

In 2008, ICCAT introduced the Bluefin Tuna Catch Document Scheme (BCD). The European Commission has praised the program, promising that “documentation of every stage in the chain, including transhipping, caging, harvesting, importing, exporting and re-exporting” would help “ensure complete and reliable traceability.”

Under the BCD system, vessels are given a unique number for each catch. That number follows the catch to ranch, through harvest, and finally to market. All along the supply chain, players are required to provide detailed information about the number, size, and location of the fish.

The system has not worked as planned. No one within ICCAT’s compliance committee has analysed the database, according to committee chairman Christopher Rogers. He said the database had too many limitations — such as countries that still had not turned in documents from 2008, although the regulations require reporting within five days.

ICIJ gained access to the internal database through an ICCAT country member and conducted its own analysis. The analysis found that the tracking system is full of holes. During 2008 and 2009 reports on more than three quarters of all purse seine catches — which make up about half of the overall catch — are missing information that would enable one to verify their legality.

In more than a dozen ranches, many more fish were being sold than could be accounted for, according to the database. In more than 130 cases — accounting for 715 tons of bluefin — vessels reported catching hundreds of fish at a time, with a mean weight at the minimum legal size. That would mean either all the fish were exactly the same weight, or many were under the legal limit to balance those over the limit.

ICIJ asked Rogers if he had ever heard complaints about the minimum-sized catches. Rogers said cases like these have caused raised eyebrows in Japan. “They’re saying, ‘Hey, your numbers seem to be doctored. It appears to us these entries were manufactured to fit the rules.’”

While fishing companies widely ignore ICCAT’s new system, questionable practices persist at sea, suggesting the Wild West of bluefin fishing has yet to be tamed. The EU's Commissioner on Maritime Policy reported in a 2008 annual report that eight Italian vessels had overfished their quota that year and eight planes were found to have been illegally cruising for tuna. Officials from the EU’s inspection arm, the Community Fisheries Control Agency (CFCA), reported 55 suspected violations in 2008. The following year suspected violations jumped to 92 — many for failing to transmit satellite position, which is used to assure that vessels are fishing within legal areas. Italy was by far the top offender, with 68 of the alleged infractions. Croatia, China, and Algeria did not transmit vessel locations during the entire fishing season. Many more vessels were out of inspectors’ reach, fishing in national waters like those of Libya, which, despite being an ICCAT member, does not welcome EU inspectors.

By September this year, the CFCA had detected more than 50 suspected violations. The agency can add one more to its list: in October an Italian fisherman from Cetara was caught with 500 baby tuna weighting an average of just one kilo each.

How bad is the situation? It’s difficult to know because a culture of secrecy has permeated oversight. Despite repeated ICIJ requests, officials at national ministries, the CFCA, the EU, and ICCAT all have refused to make public any records regarding suspected violations or their agencies’ enforcement actions.

“I can understand there is a need for transparency here,” European Commissioner for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Maria Damanaki told ICIJ in an interview. “If any case is complete you should have the full data.” The Commission, however, has denied us access to even those records.

The response buttresses concern expressed by independent auditors from both ICCAT and the EU about secrecy and lack of enforcement. “Procedures for dealing with infringements do not support the assertion that every infringement is followed up, and even less that it is subject to a penalty,” the 2007 report by the EU Court of Auditors noted. Fisheries management organizations “must find a way to be more inclusive and open in their culture,” read a scathing 2008 ICCAT review.

The new players

Meanwhile, a new cadre of players has emerged in North Africa. The 80-degree waters off Libya’s coast — a perfect feeding ground for spawning bluefin — have long attracted French vessels, whose owners have made deals with Libyan companies. Captain Jean-Marie Avallone made one of the most prominent deals, building a partnership in the early 2000s with Ras Al Hilal Marine Services — a prominent Libyan company widely reported to be controlled by President Moammar Gadhafi’s son, Saif al Islam. Sète’s leading fishing companies followed suit.

The Libyans care little about inspections, fishermen say. French Captain Vincent Caci described local inspectors as young and uninformed about tuna. When a catch would come in, one inspector simply asked Caci how many tons to write down for his report.

“They didn’t care about the fish,” he said. “They just cared about the money. They never asked us how much we fished.” Officials in Europe really don’t know to what extent Libya is — or is not – enforcing the international regulations. The same goes for Tunisia, which overfished its quota in 2008 by more than 300 tons but took no actions against its vessels.

Meanwhile, in Algeria this year, ranking officials of that country’s Ministry of Fishing were convicted of trafficking in illegal tuna, influence peddling, and tax evasion during 2009. Four Algerians — including the ministry’s secretary general — and five Turkish fishermen were sentenced to prison terms and fined €80 million.

But it is Turkey that officials say now shows the most flagrant disregard for ICCAT rules. “The massive fraud today is being committed by the Turks,” said one French maritime investigator. ICCAT scientist Fromentin faulted the combination of the country’s tiny quota and bloated fleet.

“The Turkish fleet doesn’t seem to follow the rules,” French inspectors reported in a diplomatic dispatch after repeatedly stopping Turkish vessels last year. “Their registration documents are not complete, or don’t exist at all. They don’t carry ICCAT observers on the purse seiners, or in some cases aren’t even registered with ICCAT.” In one case involving a Turkish fishing and ranching company, inspectors found the number of fish caught was underestimated by a factor of ten.

Turkey, like the North Africa states, is an ICCAT member, but with the black market trade in tuna moving across the Mediterranean it may be hard to stop the plundering of bluefin without a far more serious — and comprehensive — crackdown. Commissioner Damanaki — a Greek national — has met with Turkish officials to discuss their compliance. She hopes that, coming from the region herself, she’ll be more convincing.

“I am coming from a Mediterranean state,” she explained with an apologetic shrug. “So I can say — in the Mediterranean, compliance is not our strong point.”

Jean-Pierre Canet is a French producer and director of the documentary Global Sushi. Data analysis by Kate Willson and David Donald.