An infamous tax haven in the heart of Europe and two of Africa’s largest economies will force companies to declare their owners, joining a growing list of countries responding to public pressure over crime and tax avoidance enabled by anonymous corporate vehicles.

Cyprus, Ghana and Kenya have finalized so-called “beneficial ownership registries” that require local companies to declare owners to national authorities. Law enforcement, transparency activists and tax inspectors have long recognized the value of such disclosures in deterring criminals and corrupt officials.

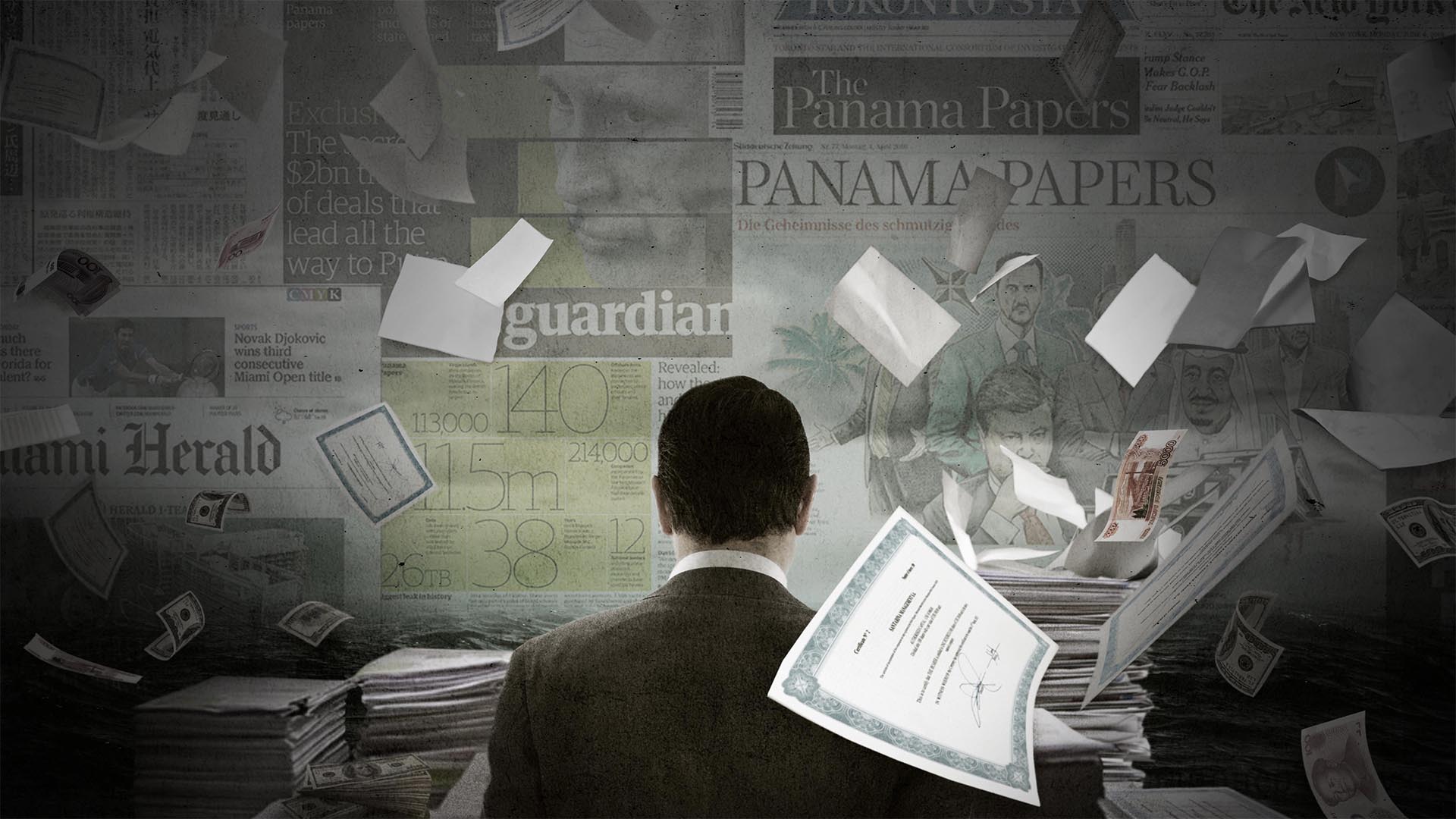

Spurred in part by scandals such as the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ 2016 Panama Papers investigation, more and more countries have enacted laws to create such registries or signalled an intention to do so.

Progress has been “considerable,” according to a 2020 review by the Tax Justice Network. As of February 2020, 81 countries approved laws requiring ownership information to be registered with national governments — more than double the number two years earlier.

In January, the United States Congress passed the Corporate Transparency Act, which requires company owners to identify themselves to the Department of Treasury. U.S. companies, especially limited liability companies, have a long history of abuse by fraudsters and foreign kleptocrats.

“Publications like the Panama Papers or the Paradise Papers have sparked an international awareness of how individuals take advantage and even abuse opportunities for tax evasion or fraud, through complex networks of offshore legal structures, but very opaque,” said Idriss Linge, a Cameroonian finance journalist and researcher. “The fact that the debate is internationalizing creates a snowball effect.”

Last month, Cyprus announced plans to introduce its ownership register, a requirement of the Mediterranean island’s membership of the European Union.

The move was warmly greeted by anti-corruption campaigners, especially in Russia and other former Soviet Union nations. Cyprus has long been a favored destination for Russian money – dirty and clean – thanks to a generous tax treaty between the countries and to weak Cypriot laws and enforcement. In 2019, the global anti-money laundering watchdog, the Financial Action Task Force, chastised Cyprus for “major shortcomings,” including a poor track record of tracing criminal proceeds generated outside the island. Authorities did not proactively track and freeze corrupt foreign money, the report said.

As part of ICIJ’s Panama Papers investigation, reporters revealed how Cyprus played a central role in suspicious money movements tied to a friend of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

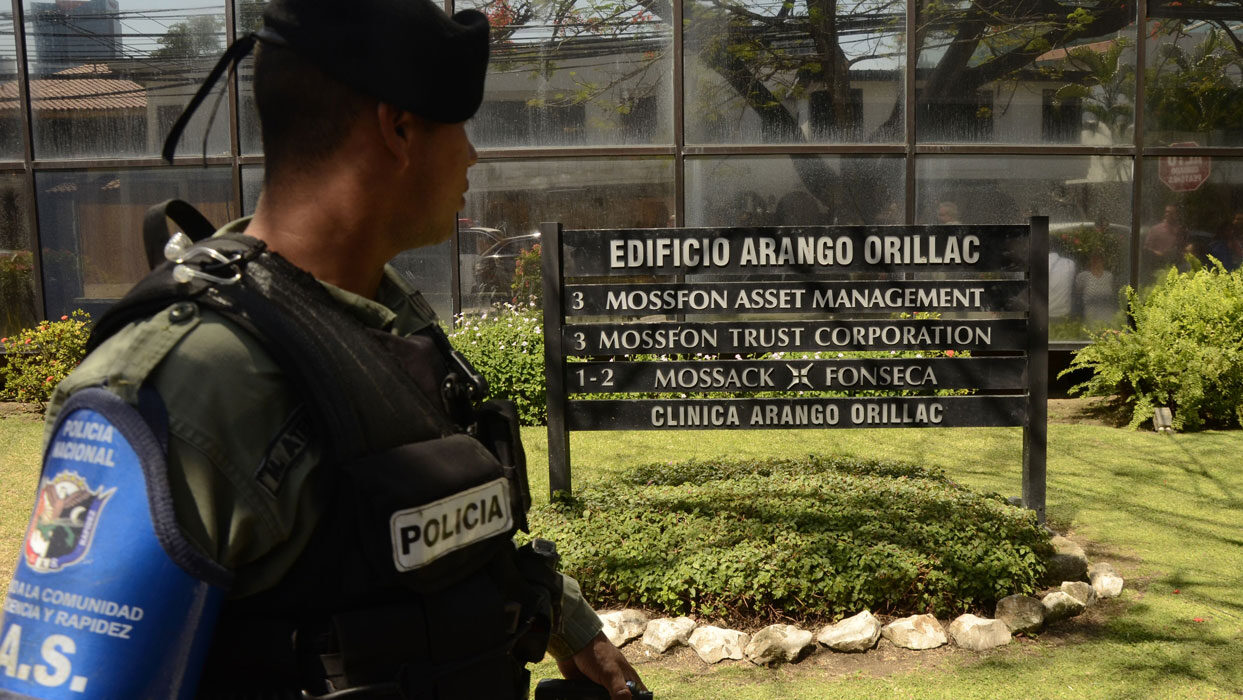

“I believe this is delicate,” Panama-based attorney Jurgen Mossack emailed colleagues at the time about a $103 million deal that passed through Cyprus. Mossack was a co-founder of the law firm Mossack Fonseca, whose leaked files formed the basis of the Panama Papers investigation. He worried that “we could be witnessing payments of questionable origin and purpose,” according to the email.

Experts told Reuters in January that the new register may prompt company owners to flee Cyprus and establish companies in countries that do not have ownership reporting requirements.

The register’s contents will not be publicly available, however, frustrating advocates who argue that public information helps banks, researchers, policy makers and journalists.

In Ghana, officials earlier this month finalized an ownership registry. Under new rules in the West African nation, every company must provide the Registrar General’s Department with the verified identities of every person behind each company.

“Following the release of the Panama Papers and the global efforts to address issues related to anti-corruption and tax evasion, the Ghanaian government has come under pressure to act on beneficial ownership disclosure,” said Registrar-General Jemima Oware in explaining the impetus behind the law.

Rich in gold, oil, timber and other natural resources, Ghana loses more than $1 billion every year in shadowy trade deals, according to an analysis by Global Financial Integrity.

“The beneficial ownership register is significant because it has the potential of unearthing the intertwining relationship of business entities and their shareholders thus reducing opaqueness and rather ensuring transparency,” Accra-based tax attorney Abdallah Ali-Nakyea told ICIJ. “Once funds flow can be traced and tracked, illicit financial flows will be reduced if not eliminated completely.”

On the other side of the continent, public and private companies in Kenya have until July to provide details of people who own more than 10% of locally-registered companies. Details will be shared with Kenya’s tax office and other government departments to help track illicit wealth. Kenya’s parliament also directed the country’s tax office to hire more than 2,000 new employees to track down tax cheats, according to news reports.

Francis Kairu, a Nairobi-based lawyer and researcher on illicit financial flows, told ICIJ that Kenya’s new register will help the country’s tax office and asset recovery agency “keep track of the major players behind the companies that engage in aggressive tax avoidance schemes.” The registry will also help link people suspected of crimes with assets purchased through anonymous limited liability companies, he said.

The Kenya registry, like those in Cyprus and Ghana, will not be made public despite pressure from transparency campaigners.

In general, Kairu said, “registers create an environment of greater transparency and suppress opacity.” In Kenya’s case, Kairu said, “I think in the long term it will be a major disincentive for the use of Kenya registered corporations for tax evasion, hiding illicit wealth and money laundering.”

Last week, Canada signalled that it may be next to join the club, issuing a long-awaited report on the possibility of a centralized and publicly accessible register.

Loopholes in Canadian laws make it simple to create shell companies and hide owners’ identities, according to a string of reports that coined the term “snow washing” to describe the combination of Canada’s cool weather and its lax approach to stopping money laundering.

Transparency International welcomed the government’s report but expressed concern that fears over what data became public were “too cautious and jeopardize chances for Canada to deter dirty money.”

Update April 20, 2021: This week, Canada’s government released its 2021 budget, which proposed resources to implement a publicly-accessible beneficial ownership registry by 2025.