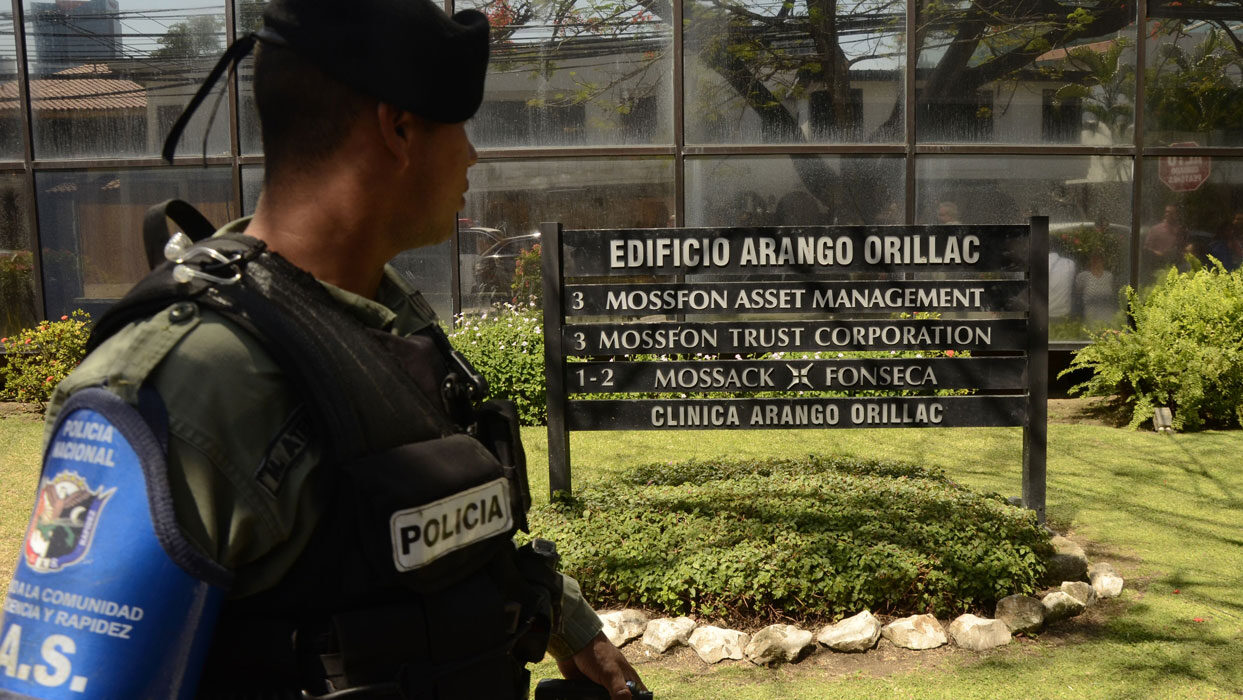

When the Panama Papers investigation was first published in April 2016, then-U.S. attorney Sarah Paul had never heard of Mossack Fonseca, the Panamanian law firm suddenly making headlines around the world.

Tapped by the U.S. Department of Justice as an experienced offshore tax bloodhound, Paul joined the team charged with America’s legal response to the Panama Papers investigation. For years, Paul worked in a cone of silence, banned from reading the growing news articles related to the scandal, so as not to taint her investigation.

In December 2018, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York announced financial charges against four men. Months later, Paul joined the New York-based law firm, Eversheds Sutherland.

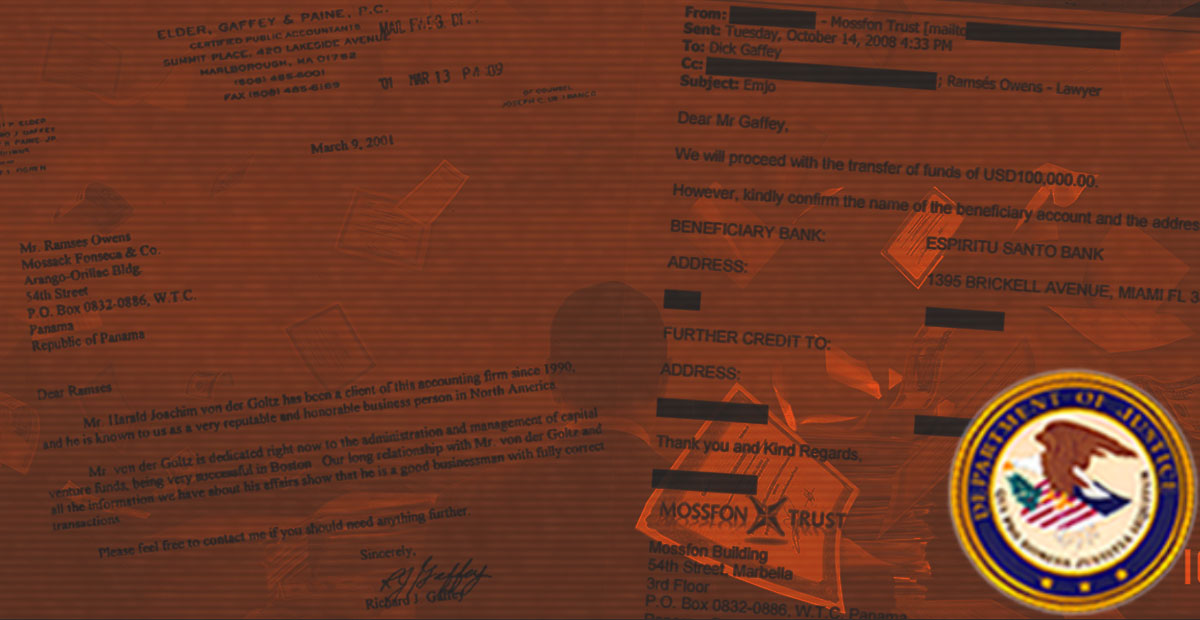

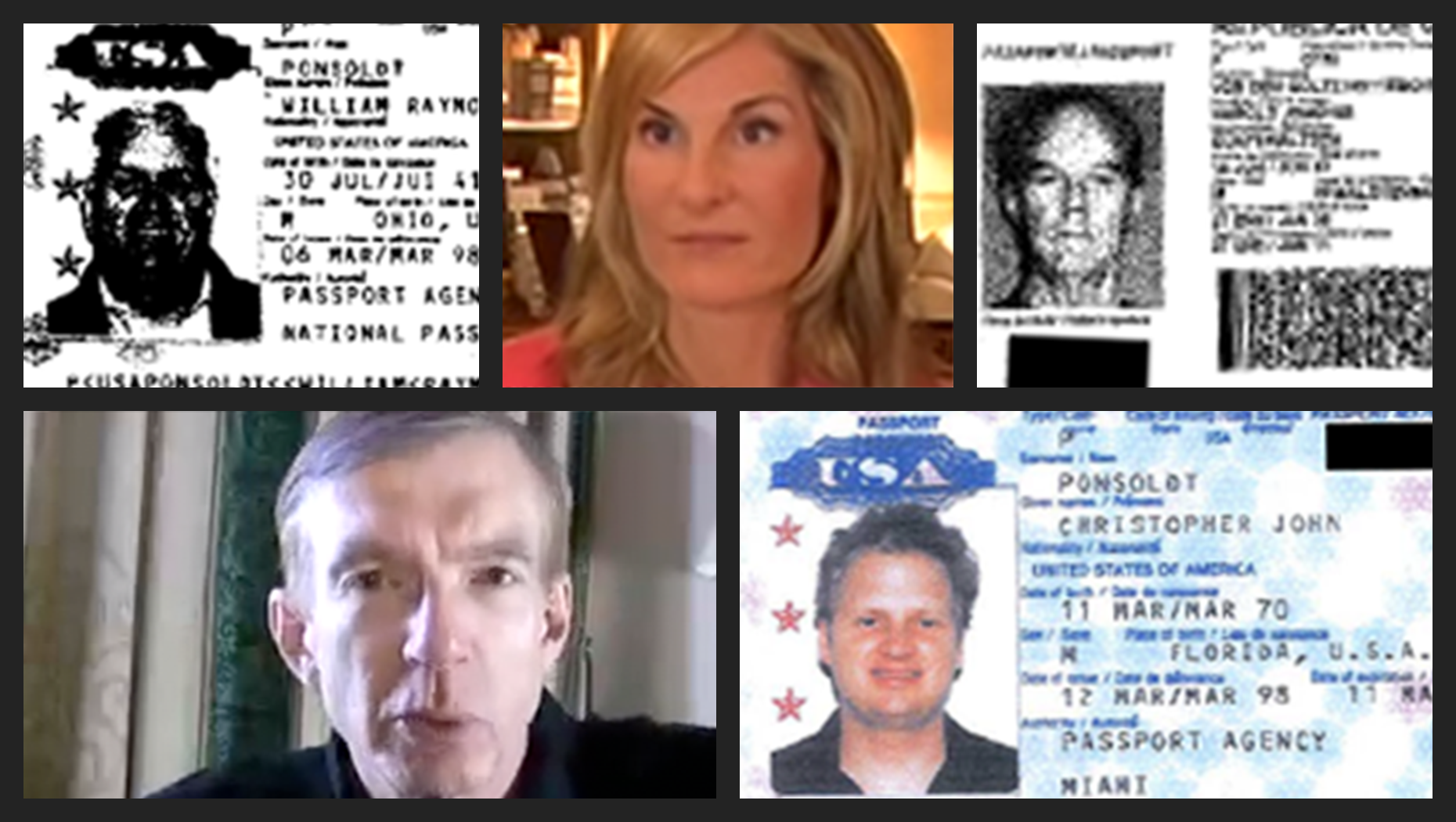

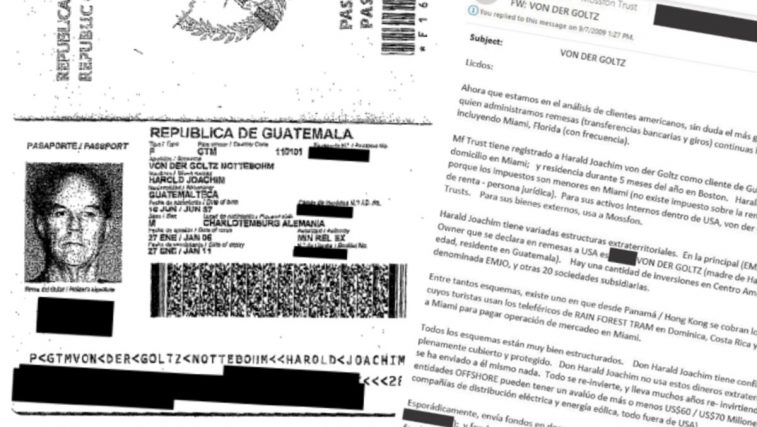

Last year, former U.S. taxpayer Harald Joachim von der Goltz pleaded guilty to fraud, conspiracy to commit money laundering and other crimes. He was sentenced to four years in jail. His accountant, Richard Gaffey, pleaded guilty to eight felonies and was sentenced to more than three years behind bars. The case continues against former Mossack Fonseca employees, Dirk Brauer and Ramses Owens.

How did you find yourself working on the Panama Papers case?

I worked as a prosecutor at the Southern District of New York for nearly nine and a half years. As I became more senior as a prosecutor, I did more and more sophisticated white-collar cases, investigations, and prosecutions. I think it was 2013 when I started in the complex fraud and cybercrime unit and started to work on the offshore tax cases. I started off doing lots of the post-UBS cases. When I say post-UBS I mean investigating other Swiss banks for helping U.S. tax payers hide their money.

I started off working on a lot of those, investigating some of the banks, some of the bankers, the asset managers and U.S. taxpayers as well. From there, we began to expand those types of offshore investigations into other jurisdictions. There was a big case in the Cayman Islands and another one in Israel. All were in pursuit of the same goal, which was to combat offshore tax evasion.

Why were these cases becoming more important?

It was a very big priority for IRS criminal investigations. Offshore tax evasion is a huge problem and for many years, starting with Switzerland, it was impenetrable. That was really at the highest level. The Swiss government, I think, wanted to make it possible for U.S. taxpayers to hide their money in Switzerland. Frankly, it was a big part of their economy. That was something that prosecutors here and the IRS wanted to combat. It started with the UBS case, which really began to pierce the veil of secrecy. It was so successful there that we began to expand to other jurisdictions.

When did you first hear of Mossack Fonseca?

I hadn’t heard of them until the Panama Papers news stories broke.

What was the start of your involvement in this case?

I started working on the case basically from the minute you all broke the story. Obviously, it was a big story. It was a natural fit for me to work on the case as someone who already had experience with offshore tax evasion investigations.

What I want to emphasize is that we were very careful about attorney-client privilege issues from the start. The investigation team didn’t read the news articles. What we did was put a filter team in place. They read the news articles and then redacted anything that might be potentially privileged, and we read whatever was left.

It’s funny because we as the investigative team probably knew less about the case than a lot of folks in the world because we couldn’t read the news.

How many of you were on the team?

It was very big on the U.S. side. There were four prosecutors in addition to supervisory-level prosecutors. We worked with several components of the Department of Justice. We worked with the tax division, the money laundering and asset recovery section and the fraud section. There were a lot of agents from the IRS on it as well as agents from Homeland Security and the FBI at various points.

Why were so many agencies needed?

There were lots of places to go in the investigation and lots of things to run down. You also had different types of crimes. Obviously, we were looking at tax and wanted to involve the IRS. But we were also looking at money laundering and wanted to involve Homeland Security. There were possible FCPA [Foreign Corruption Practices Act] issues, so it made sense to involve the fraud section and FBI.

How did you go from a huge amount of information to winnowing it down to just four people?

We were most interested in the U.S. taxpayers who had hidden the most money. Mr. von der Goltz was someone who was identified early on as having hid quite a bit of money with the assistance of Mossack Fonseca. We were also interested in his U.S.-based accountant, Dick Gaffey. Because any time you have a U.S-based accountant involved, that’s something we take seriously.

What was familiar to you in this case?

The familiar pattern was the use of these shell companies. Using a shell company to nominally hold a bank account that has an undeclared owner is a fact pattern that I have heard time and time again.

What were some of the factoids that made this unique?

These structures were a little more complicated than I was used to seeing because you not only had the shell company you also had these sham foundations that Mossack Fonseca would create for its clients. These sham foundations were the quote-unquote “owners” of the shell companies that nominally held the accounts. So that created another layer, which made it even easier for people to hide their money.

Coupled with that was how it was really Mossack Fonseca’s M.O. [modus operandi] to create these structures for their clients. I thought that was striking, just how pervasive it was.

What’s the process for peeling away those layers and structures?

It’s a really lengthy process. It’s not an easy thing to investigate, especially when we were hemmed in a bit by attorney-client issues. We had to mine the IRS offshore voluntary disclosure program for taxpayers who might have dealt with Mossack Fonseca. We issued subpoenas to customers of Mossack Fonseca to get records of other accounts. We relied on the treaty process a lot to try to get offshore bank records. We went to banks who participated in the Swiss banks program who had certain cooperation obligations and got some information from them.

But it’s hard. It’s hard not only to pierce that veil but to prove intent. That’s one of the reasons it took so long.

Was there a eureka moment during your investigation?

We executed a search warrant on Dick Gaffey’s accounting firm and we found a lot of helpful material. We had already subpoenaed Mr. Gaffey and the firm. We didn’t feel like we had gotten all the documents that were out there in response to that subpoena. After we did the search warrant, we realized we were correct and there was really a lot more.

What about the 100-year-old grandmother who von der Goltz claimed was the real owner of the shell companies?

That’s how Mr. von der Goltz set things up. He put her down as the beneficial owner of these accounts and these assets. But that really was a lie — she wasn’t. That was a key part of the scheme. I will say that I have seen that before. Putting down your elderly relatives as the real beneficial owner of your money — Mr. von der Goltz did not invent that practice.

What about Brauer and Owens?

I wouldn’t expect that to be over just because they haven’t been heard yet.

Is this kind of stuff still happening or are the facts from the Panama Papers case things of the past?

I think it’s still happening to a reasonable extent. I think there are still service providers out there like Mossack Fonseca who are engaged in similar activities.

[Editor’s note: Mossack Fonseca was shut down in 2018.]

What do you think has changed since you first investigated the Panama Papers case?

I see the new Anti-Money Laundering Act is a game changer in terms of how these investigations are covered. As part of that, the Corporate Transparency Act is going to require certain companies to provide beneficial ownership information to FinCEN [the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network]. That part is obviously important.

I think from an investigation standpoint, the new mechanism about how to obtain foreign bank records is significant. Under the new AML Act, if a foreign bank maintains a U.S. correspondent bank account, a U.S. prosecutor can issue a subpoena requesting any records related to any account at the foreign bank, including records maintained outside the US. That subpoena power is not limited to records related to the U.S. correspondent account, which is the limitation that existed previously. While a foreign bank could move to modify or quash the subpoena, there’s language in the new Act that prohibits the court from doing so on the sole ground of compliance with foreign bank secrecy or confidentiality laws.

Had this been in place when I was investigating the Panama Papers, I think it would have made a significant difference. We were able to get foreign bank records through the treaty process. But getting those records would have been much easier and quicker under the new AML Act.

Most of the U.S. taxpayers … didn’t have a very high level of sophistication about how to hide their money. They rely on the middlemen or the enablers to give them the tools.

If you had a magic wand, what would you have changed to make the investigation easier?

I think if we hadn’t had to contend with attorney-client privilege issues and had just read the news in full and followed every lead we found, it would have been much easier. To not have to have a filter team would have made the investigation much more streamlined. But obviously we weren’t in that position and had to be careful.

The fact Mossack Fonseca was a law firm was the issue. I had wanted to make the argument in the case about whether it was really the provision of legal advice because this was advice on how to set up structures to hold money. There is an argument that that is not really legal advice at all — you’re acting as a service provider.

One of the things that we always wanted to tee up was this argument about when the privilege has been broken under a “widespread dissemination theory”’ The theory is that because of all the widespread reporting about the Panama Papers and because of the failure of any client to come forward and still claim privilege over the documents, the privilege had been waived. I would expect those types of arguments to be made in the future by prosecutors.

How important is the role of enablers?

They play a critical role. Most of the U.S. taxpayers, though certainly not all of them, who I encountered when I was a prosecutor didn’t have a very high level of sophistication about how to hide their money. They rely on the middlemen or the enablers to give them the tools to do it.

Two Americans have been prosecuted and sentenced. Does that mean there weren’t many Americans involved?

It takes a lot to make a case like this and you’re not going to be able to make it against everyone. We also have to remember the offshore voluntary disclosure program through which people have the ability to come into that and not be prosecuted. You’re not going to see a prosecution of every U.S. taxpayer who dealt with Mossack Fonseca. I would also add that the investigation is not over. I’m no longer with the US Attorneys’ office but the investigation has not been closed.

Join us on April 15, 2021, for a free, online event marking five years since the Panama Papers, featuring documentary filmmaker Alex Winter, and award-winning Panama Papers journalists Emilia Díaz-Struck, Bastian Obermayer and Rita Vásquez.