PRESS FREEDOM

‘It is still dangerous to be a journalist’: Daphne Caruana Galizia’s son reflects on her life and legacy

Paul Caruana Galizia’s new book grapples with the seismic impact of his mother’s murder, and how her fearless reporting may have saved Malta from becoming a “mafia state.”

Paul Caruana Galizia had just sat down for an after-lunch coffee with a friend in 2017 when his brother called with the news that their mother, journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, had been killed by a car bomb.

The bomb was detonated remotely in a planned assassination that took place minutes after Daphne left the family’s home in Northern Malta.

A prolific investigative journalist and blogger, Daphne was already a household name, known in the small island nation and beyond for her cutting columns and exposés on organized crime and rampant corruption at the highest levels of government.

But her murder, at a time when she was investigating a kickback scheme involving then-prime minister Joseph Muscat and two of his closest aides, led to protests in the streets and caused an international outcry over threats to freedom of the press. That reporting built on Daphne’s findings as part of ICIJ’s groundbreaking Panama Papers investigation, and linked the three men to offshore companies connected to the sale of Maltese passports and payments from the government of Azerbaijan.

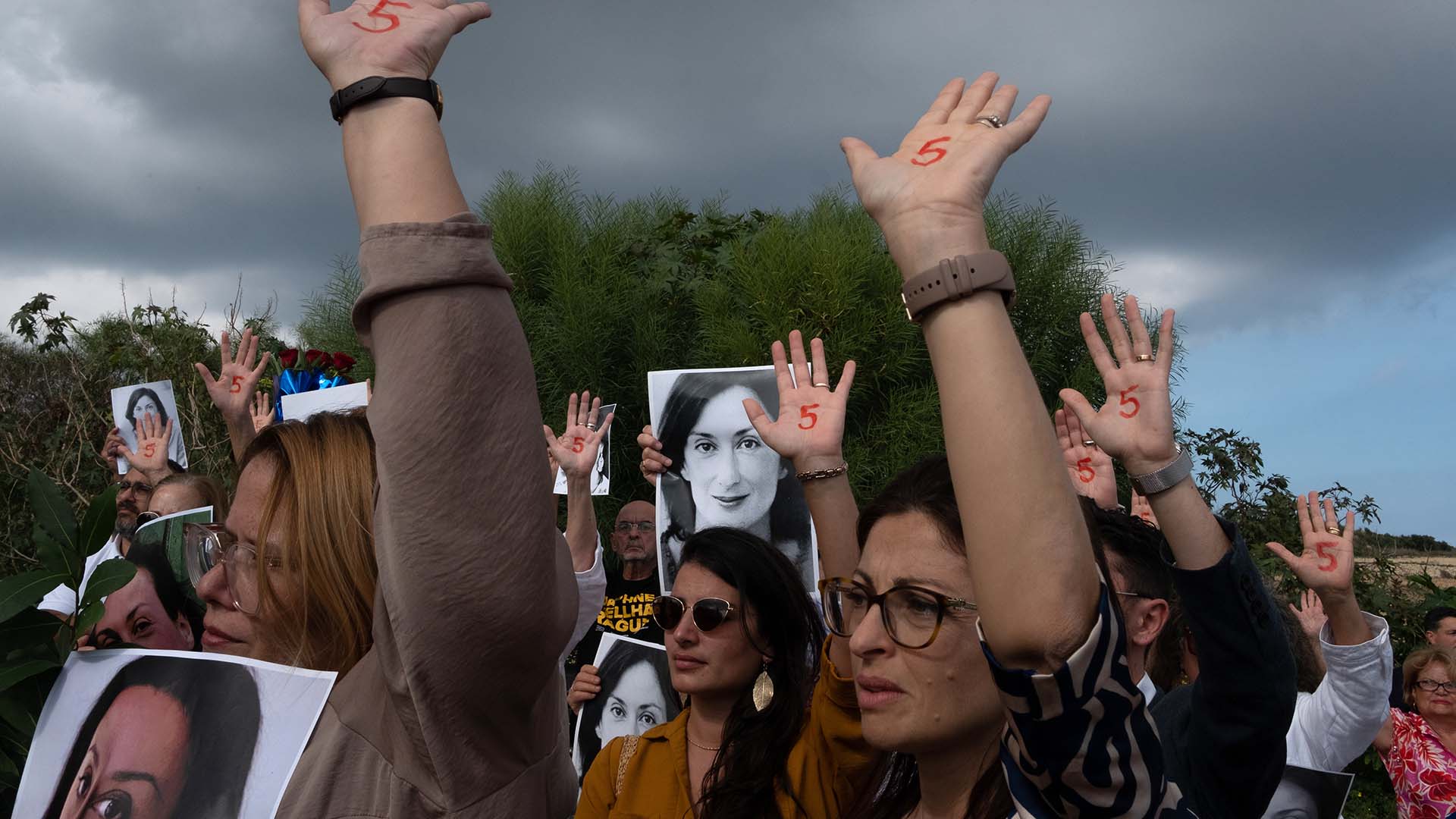

Amid the widespread condemnation of the Maltese government for failing to protect her were calls for reform, including from Paul and his family. Then came the protracted court battles to hold Daphne’s killers accountable. Three people have so far been convicted for the murder, with several separate trials still ongoing. In 2021, a Maltese public inquiry concluded that the state also held responsibility for the assassination by failing to act on threats to Daphne’s life and fostering an “atmosphere of impunity.” Her assassination, the judges wrote, put a brake on Malta’s predicted decline into a “mafia state.”

“So often we would literally go from one courtroom to another in the same day,” Paul told ICIJ. “My mother had been reduced to a person in a murder investigation, and there was this fullness of her life that had been completely lost. And that’s when I started thinking about the book.”

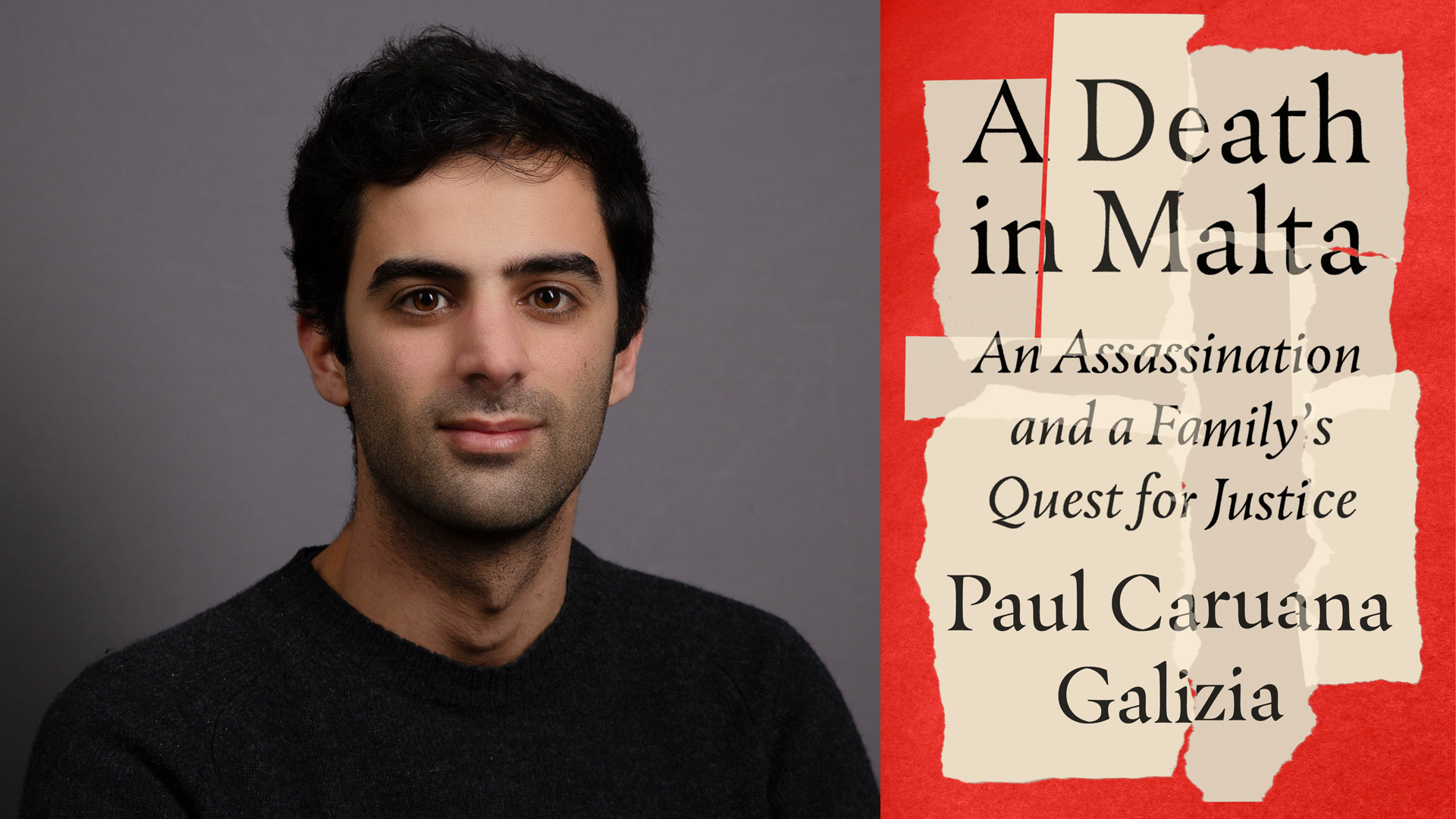

That book came to fruition in 2023 as “A Death in Malta: An Assassination and a Family’s Quest for Justice,” published close to the sixth anniversary of Daphne’s murder.

ICIJ spoke to Paul about distilling his mother’s life into words, the legacy of her decades-long career, and the current state of press freedom in Malta and around the world.

What was the process of reporting on and writing about your own mother like for you?

It’s strange because first you have to accept that there’s so much about your mother’s life you don’t know. And that’s quite a funny feeling. It’s almost always true that we have limited knowledge of our parents’ lives because we rarely ever know when they were like us, children, teenagers and so on. So I didn’t even know the most basic things. For example, why did she become a journalist? Why did she become a journalist when she did? How did she meet my father? I’d started chronologically, with my maternal grandparents, and then her high school friends and her first boyfriend. Slowly, I started building up this profile.

You realize how funny memory is, in general, and that different people often remember the same events totally differently. It took a lot of reporting to find out, for example, how she got her column with The Sunday Times in Malta, because no one could remember exactly how it came about. You remember it one way, and you have to collect the facts and you have to put them in order.

As much as it is a history of your mother and a history of your childhood, it’s also sort of a retelling of Maltese history, isn’t it? How did you come to use that as a framing device?

I was initially not keen on having the Maltese history in the book — a very early draft had little of it. But then my American editor politely said, “Paul, I’m afraid to tell you, people outside Malta don’t really know it exists.”

My mother was born two weeks before Malta became independent from Britain. And, I thought, that’s so strange. Malta came into being when my mother was born. And you can really tell the arcs of their lives are in parallel. It became very obvious as I was interviewing her childhood friends and her early colleagues, and reading her opinion columns, that my mother’s life is part of Malta’s history, and Malta is part of her life. And her opinions were shaped by going from a very closed, very socialist economy and government to a more pro-West one and our accession to the European Union. It became, I realized, impossible to do it any other way.

How did looking back on Malta’s history change your understanding of the country?

I never appreciated how far back this really unfortunate partisan division went. In the ’80s, especially, things became very violent. There were unsolved murders, bombings, shootings, a lot of protests. And then in ’87, we elected a new party to power and began turning the country West again and opening up the economy. And that party had promised a sort of reconciliation, once in power, to address these events. But it never happened.

I was born in ’88. It made me think a lot about how difficult things become when you paper over the past. You have all these open wounds and they matter. There’s no sense of justice, no sense that things have been resolved, and that informs public debate. It informs how people treat each other. It affects how people feel about the state, whether it’s a legitimate part of their lives or not. Because Malta is a young country, really, and the state’s legitimacy is weak. People lost faith in the idea that the state can prosecute corruption and address really serious crime.

How do you feel about the broader state of press freedom right now, in Malta and beyond?

It holds that it is still dangerous to be a journalist. There are a number of journalists who are doing incredible work, uncovering really serious corruption, picking up on my mother’s stories. And there’s nothing to support the statement that things are better for them or that they aren’t subject to the same risks my mother faced.

The best way to protect journalists doing this kind of work, and to create a really safe media environment, is to have an official response to the journalist’s work. My mother would uncover really serious corruption, but then nothing would happen. The police wouldn’t investigate. There’d be no judicial inquiry. So it ended up being my mother versus the subjects of her reporting. Matthew, my eldest brother once described it as there being nothing standing in between her and the collapse of the rule of law. So, of course, they only needed to cut down my mother, rather than a police officer or a judge or a magistrate.

Things have changed. The risks are still the same, but there are more voices now.

— Paul Caruana Galizia

That’s what really needs to change in countries like Malta, where corruption is endemic, because reporters are often the last check on the abuse of power in their country. They don’t have any official power. The public inquiry made a number of recommendations to change things, but not a single one of those recommendations has been implemented. So again, they are as exposed as my mother was.

What’s the state of investigative journalism in Malta, now that she’s gone?

Well, it’s really interesting because, especially in the last five years of her life, she was really isolated. Every major investigative story was hers. She resented that, she felt like, why aren’t people picking up on my stories? Why am I so exposed? Why do I have to do all the work?

Things have changed. The risks are still the same, but there are more voices now. A new website formed called The Shift News, which is run by Caroline Muscat, who is a really good journalist. And it’s done really, really important investigative work on corruption and on abuses of power. And that’s totally new, and it was formed in response to my mother’s murder. Journalists at other papers have become emboldened, in a way, and that’s because so many journalists outside the country took an interest in Malta and Maltese stories. So they felt part of a bigger community, and that they could join forces with these much bigger, more established media organizations.

Your mother was reporting Panama Papers revelations when she was killed. What’s the legacy of her accountability reporting in Malta?

The Panama Papers, and not just my mother, was a huge moment. It kind of showed people how things really work. There’s this whole other world, this whole other secret layer of how money is moved around and hidden and made and all the people who enable it, kind of exposed overnight.

It shouldn’t take another murder to take notice.

– Paul Caruana Galizia

If there’s a specific legacy of my mother’s, it was to show the same thing for Malta. Of look, our politicians are also doing this. Our accountants are also doing it. And that financial crime and corruption is a really serious global issue. The way my mother reported it, as well, was to make it colorful. It’s changed the way people see their politicians. They now expect more transparency of their governing class.

What is still left to be done? What do you want people reading this to keep in mind or take away?

That global corruption is one of the defining issues of our time, and that we need better ways of fighting transnational corruption. Journalists who are reporting on it and exposing it are at risk wherever they are, because they’re up against really serious forces: really, really rich people, and really hard, difficult work uncovering flows of money and companies. We should listen to them before they’re murdered. It shouldn’t take another murder to take notice of that.

Of course, my mother was murdered in an awful, awful way. And we are years away from justice for her death and her stories. But still, her story shows the power of journalism to change our country and to change lives. You know, it was journalism that did it, in the end. It’s journalism that changed the course of Maltese history.