WHISTLEBLOWERS

Panama Papers source says ‘Russia wants me dead’ in first-ever media interview

“John Doe” told German news outlet DER SPIEGEL that he was “astounded” by the success of the investigation, but more needs to be done to clamp down on financial secrecy.

The source behind the Panama Papers leak still fears for his and his family’s safety, six years after the global investigation rocked the world of offshore finance.

Speaking with German reporters Bastian Obermayer and Frederik Obermaier in his first interview since 2016, the source, who calls himself John Doe, cited the murders of investigative journalists Daphne Caruana Galizia and Jan Kuciak and said he still feared retribution for his part in exposing the financial secrets of some of the world’s most powerful and dangerous people.

“It’s a risk that I live with, given that the Russian government has expressed the fact that it wants me dead,” he said in the interview, conducted for German news outlet DER SPIEGEL.

John Doe said he was motivated to speak out by a growing sense of “instability” in the world, and from disappointment that more hasn’t been done to clamp down on a secretive financial system that props up autocrats and enables people like Russian President Vladimir Putin to launch a war in Ukraine with little accountability.

“Putin is more of a threat to the United States than Hitler ever was, and shell companies are his best friend,” he said. “Shell companies funding the Russian military are what kill innocent civilians in Ukraine as Putin’s missiles target shopping centers.”

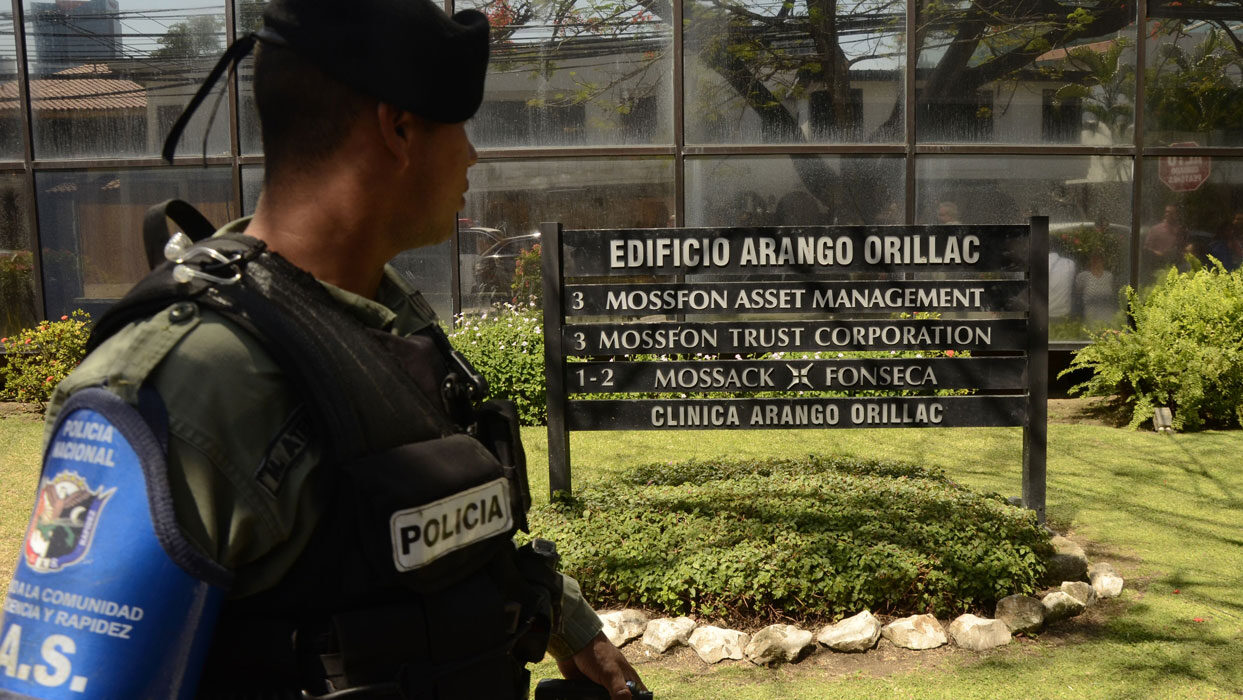

John Doe first reached out to Obermayer, then a reporter with Süddeutsche Zeitung, in 2015, shortly after the newspaper published a story about a raid on a German bank sparked by a leaked dataset from a little-known law firm called Mossack Fonseca. German authorities had purchased this first dataset from a source who later gave the materials to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the German reporters.

Contacting Obermayer over an encrypted messaging service, John Doe offered another, larger, trove of data from inside Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian law firm that specialized in setting up offshore companies in tax havens. The Süddeutsche team shared the new files with ICIJ, which brought together more than 370 journalists from all around the world to investigate the 11.5 million-file dataset — one of the largest leaks of financial data in history.

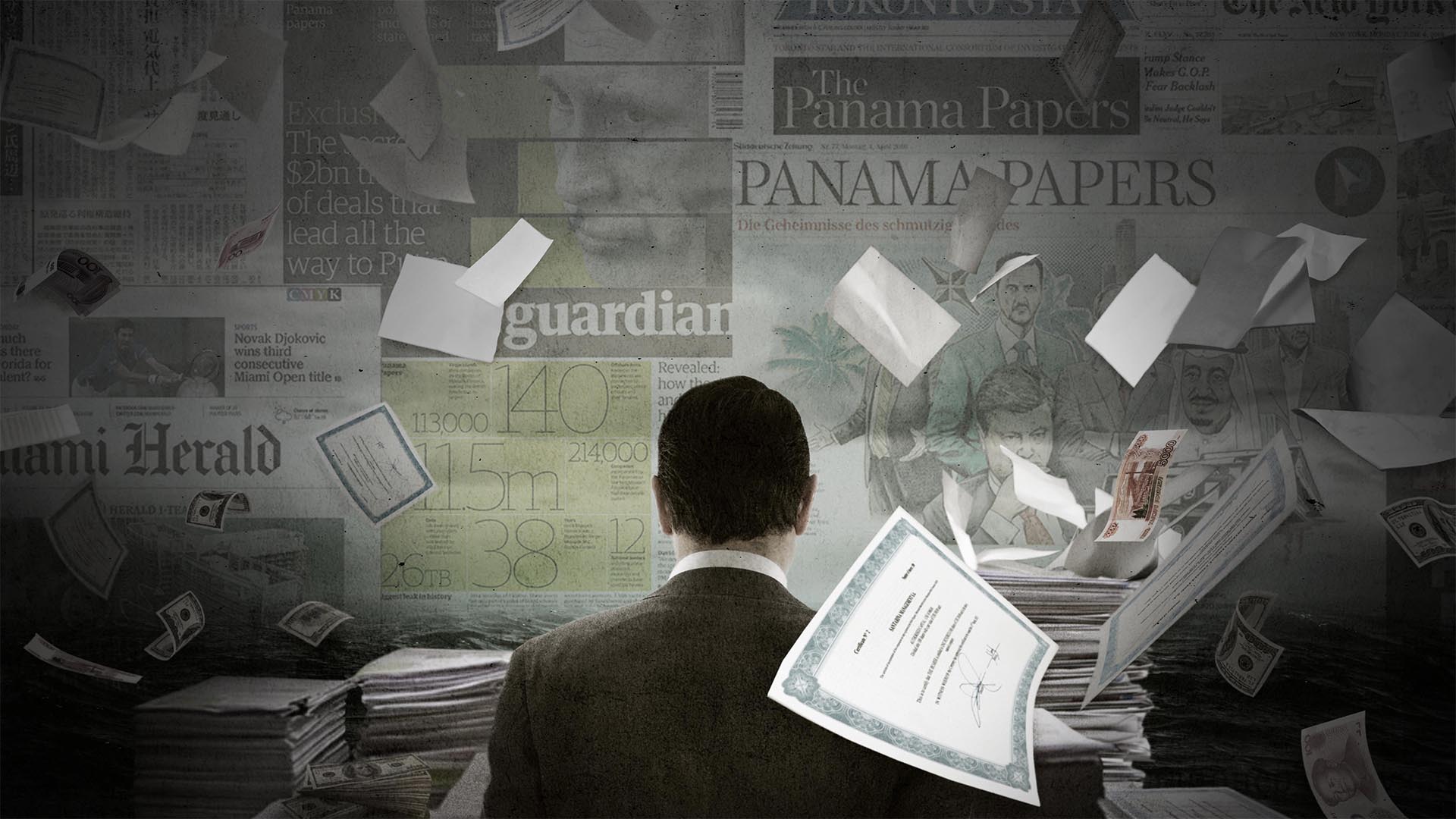

What became known as the Panama Papers was published in April 2016, and quickly became the most talked-about story in the world. Investigations from more than 100 media outlets exposed the secret offshore dealings of 140 politicians, as well as a bevy of celebrities, criminals and more, including some of Putin’s closest allies. Within hours protests had broken out on the streets of multiple countries, and the ensuing scandal led to the ouster of numerous officials and leaders, including the prime ministers of Iceland and Pakistan. Authorities around the world have launched hundreds of investigations, and have clawed back more than $1.36 billion in lost tax revenue as a result.

I never thought that releasing one law firm’s data would solve global corruption full stop, let alone change human nature. Politicians must act. — John Doe

Since then, the Panama Papers has become a global touchstone of the debate around corruption, financial crime and inequality. Six years later, it is cited frequently in news reports, parliaments, courthouses and popular culture, inspiring more than a dozen books, a Hollywood film and multiple documentaries. Through it all, John Doe’s identity has remained a secret.

“I am astounded with the outcome of the Panama Papers. What ICIJ accomplished was unprecedented, and I am extremely pleased, and even proud, that major reforms have taken place as a result of the Panama Papers,” John Doe told DER SPIEGEL.

“The fact that there have been subsequent journalistic collaborations of similar scale is also a real triumph. Sadly, it is still not enough. I never thought that releasing one law firm’s data would solve global corruption full stop, let alone change human nature. Politicians must act.”

In the interview, John Doe said he was unhappy with his experience sharing the Mossack Fonseca files with the German government for a reported 5 million euro (about $5.6 million) reward (Doe said the German government “did not actually honour the financial agreement”) and hinted at even more information that has not yet come to light.

“The German Federal Police have repeatedly turned down the opportunity to analyse more data about the offshore world beyond the Panama Papers, which is frankly shocking,” he said.

ICIJ Director Gerard Ryle said whistleblowers like John Doe were vital to piercing secretive industries, like those that provide shelter to criminals and corrupt politicians, and said investigative journalism had a track record of triggering significant positive change for society.

“Stories like the Panama Papers and Pandora Papers have brought global scrutiny to a secretive financial system that has thrived in the shadows for far too long,” he said. “ICIJ’s model brings together hundreds of the world’s best reporters to do what authorities can sometimes struggle to pull off — meaningful, unfettered collaboration across borders. Reporters working together can expose wrongdoing in a way that has a genuine impact, and gives the world an opportunity to right wrongs and change things for the better.”