In early 2021, Eli Luchak, a bartender and singer in New Orleans, was trying to conjure up a name for the Southern sludge/metallic hardcore band he and five other twenty-something friends were putting together.

One early idea for the group’s name had been Poodle Moth, a reference to a mysterious and fluffy insect that’s been spotted just once, in the Gran Sabana region of Venezuela. But that didn’t capture the kind of loud and politically passionate music Luchak and his bandmates were gravitating toward.

So he started thinking about a global event that had caught his attention back in 2016, during his sophomore year of high school in Philadelphia: the Panama Papers investigation.

For Luchak, the collaborative journalism initiative had been a moment of political and economic illumination that helped him understand “how the world works.” The Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation, which revealed names and other specifics of powerful figures who exploit offshore financial secrecy at the expense of the rest of the world’s population, offered Luchak a possible name that could speak to his awakening.

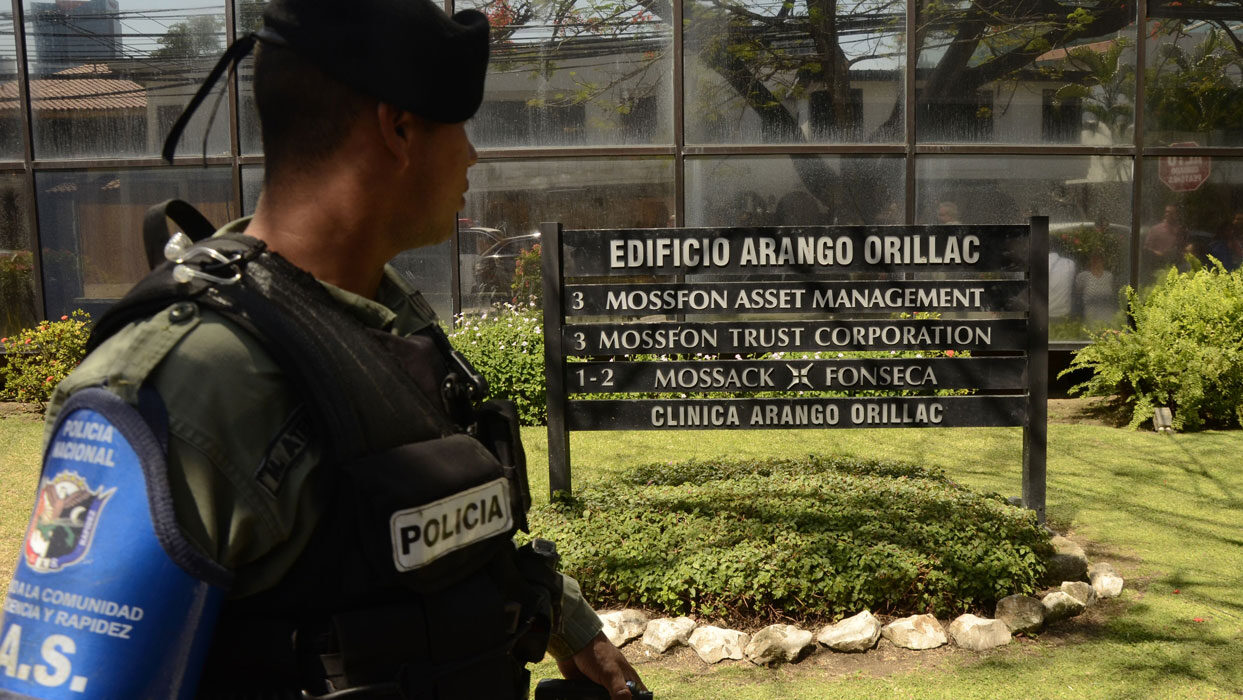

He suggested calling the band Mossack Fonseca, after the Panamanian law firm at the center of the Panama Papers. Or Panama Papers Shredders, playing off the idea of hidden documents being destroyed but also the “shredding” style of guitar work often used in heavy metal.

Neither of those quite clicked. He and the band decided that a straight-forward and alliterative name — Panama Papers — was the way to go. After an intense period of songwriting and practicing, they’ve been playing under that name at house parties and clubs around New Orleans for a year now.

The band’s name is a testament to the cultural impact that the Panama Papers investigation has achieved since it debuted on April 3, 2016 — seven years ago today.

The investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and more than 100 media partners helped oust prime ministers in Iceland and Pakistan and sparked arrests, new laws and government probes in dozens of countries. Today the Panama Papers endures as a catchphrase that helps frame and fuel public debates about corruption, financial crime and inequality.

At the same time, the Panama Papers’ influence has stretched far beyond legislatures and courthouses. The investigation has penetrated deep into global popular culture, inspiring movies, books, artworks and a variety of musical projects — all of which have helped keep its memory and impact alive in public consciousness.

The New Orleans-based band Panama Papers is one of at least five musical groups around the world that have named themselves after the investigation. At least 11 record albums are named after the 2016 investigation. And musicians in multiple countries and languages have written, recorded and performed at least 38 songs titled “Panama Papers” or some variation, such as “Panama Papers Blues.”

These songs rise up from many genres, including punk, funk, metal, techno, ambient, lounge, dubstep, indie rock and free-form jazz. Some are instrumentals, but others feature lyrics that directly address injustice and inequality and their enablers in the offshore financial world.

Vanquished Kingdom, an Australian metal band, released a song called “Panama Papers” in 2018 that includes these in-your-face lyrics:

White washed tombs, corrupted hearts

the Almighty Dollar’s shills,

it’s all legal, never mind

who it robs or kills

Siebe Pogson, the band’s bassist, says his bandmate and cousin Zac Anderson wrote the song “as an angry reaction to the story as it was breaking” — including the revelation that Australia’s prime minister at the time, Malcom Turnbull, had been director of an offshore company set up in the British Virgin Islands.

“It was one of our favorite songs to record and play live, especially as it has so much energy,” Pogson said. “We were always able to get the crowd going at the end with the chant” — a man, a plan, a canal, Panama.

Another Panama Papers song that features an audience-rousing chant was created and recorded by Shaolin Temple Defenders, a French funk band with an affinity for James Brown and kung fu movies.

When the investigation was released, the band was in the middle of recording its sixth album. Its vocalist, Emmanuel “Brother Lion” Guérin, had already written a song about offshore secrecy titled “Another Daily Robbery.”

As news of the investigation rocketed around the world, becoming the No. 1 trending topic globally on Twitter, Guérin and his bandmates decided the song needed a new name.

“The scandal came,” bassist Jeremy Ortal said, “so we decided to change the name to ‘Panama Papers’ because it symbolized all this behavior of finance and tricks. . . . We were sure people would be intrigued by the name.”

Their artistic mission, Ortal said, drives them to raise their voices about “painful truths.” He said whistleblowers like Panama Papers’ John Doe “should have a statue in each town of the world. They are the new freedom and justice fighters.”

The band performed the song live most recently eight days ago at a show in Geneva, Switzerland.

They were singing about tax havens in perhaps the world’s oldest and most notorious tax haven, belting out a chant that tries to provoke listeners to take action:

Give back all the money

Gotta take back all the power.

Doom and noise

The Panama Papers investigation has had staying power as a cultural phenomenon in part because it hits home for many people in an era when billions of lives have been affected by political and corporate corruption, the widening gap between rich and poor and the social media-driven spread of disinformation and authoritarianism.

Mac Fisher, a guitarist/vocalist and bandmate of Luchak in the Panama Papers band, was also in high school when the Panama Papers came out. At the time, real estate impresario and reality TV frontman Donald Trump was closing in on the 2016 Republican nomination for president, fueling her concerns about how the power of the mega-wealthy was hurting people trying to get by from day to day, paycheck to paycheck.

The Panama Papers was “formative” for her as a teenager growing up in Asheville, North Carolina, she said.

“It was amazing how something so enormous could just get swept under the rug by so many people,” Fisher, now 23, recalled. “It was a reminder of who was benefiting from that — and that they, in fact, had names and addresses and corporeal forms. And it showed how much we were willing to accept and just how many unspoken, awful truths there are in the way our world operates.”

For Fisher, Luchak and their bandmates — drummer Omar Shbeeb, bassist/vocalist Soumya Ramineni and guitarists Cameron Slate and Thomas Henry Williamson — wealth inequality and economic exploitation aren’t theoretical issues. They play before audiences made up largely of young adults looking for a head-banging respite from working soul-crushing shifts at low-paid service industry jobs.

The band says its music is influenced by a variety of genres, including “doom, noise, Southern rock, bluegrass, dance, post punk, hip hop, prog, dream pop and indie rock.” The band hopes to record its first album soon.

One song that may go on the album is called “Nasdaq Prescott.” Luchak, who wrote the lyrics, came up with the song’s name by combining the name of Nasdaq, one of the world’s largest stock exchanges, with the name Prescott, which has an “old money” ring to it.

The song is a dialogue between a rich man and a not-rich person. It starts in the voice of the rich guy:

Tied to these offshore holdings

These tricks and guilts all-knowing

You breathe and sleep so hardly

I lie and kill so calmly

A horse and a ‘black-hearted’ joke

It’s not just bands and songs that carry the Panama Papers name.

Seventeen days after the first Panama Papers stories exploded into the public domain, a thoroughbred horse was born in Germany and given the name Panama Papers. It was, perhaps, a reflection of the crucial role played in the investigation by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, which obtained the 11.5 million leaked files from the anonymous whistleblower John Doe and shared them with ICIJ and other partners.

The biggest win to date for the racehorse named after the investigation came last year at Kilmore Racecourse in Victoria, Australia, where it defeated a horse called A Pinch of Luck.

The investigation also inspired flourishes of entrepreneurial creativity. At least two ventures marketed Panama Papers brand rolling papers for those who like puffing tobacco or other leafy substances via do-it-yourself cigarettes.

One offered “Offshore Flavored” palm leaf “pre rolls” that were “Made in Panama” and “100% Vegan.” Another offered Panama Papers rolling papers in packaging with the slogan “Rolling Onshore.” On a Facebook account under the name Panama Papers Inc., the second venture threw shade at the secrecy-cloaked offshore companies revealed in the investigation, announcing: “The Most Transparent Company in Human History is online now! Thanks to all that support our crazy idea to become the only 100% transparent business on Earth.”

The Panama Papers investigation has also made a name for itself in more mainstream forms of entertainment. It’s been the subject of cartoons in The New Yorker and dozens of other publications and has popped up on TV programs such as “The Daily Show,” “Last Week Tonight with John Oliver,” “Billions” and “Jeopardy!” The 2019 movie “The Laundromat,” starring Meryl Streep, Gary Oldman and Antonio Banderas, centers on the Panama Papers. At its premiere at the Venice International Film Festival, Streep said the film was an entertaining way of “telling a very, very dark, black-hearted joke — a joke that’s being played on all of us” by the clients and the enablers who make the offshore financial system a reality.

The investigation was also the subject of a 2018 documentary film by actor and filmmaker Alex Winter, “The Panama Papers,” which told the story behind the story: how a global team of journalists sifted through the secret documents and broke one of the biggest financial and political scandals in history.

Winter, best known for his role as Bill Preston in the “Bill & Ted” comedies, has directed several documentary films about social and political issues — most recently “The YouTube Effect,” an examination of social media’s role in spreading disinformation.

He worries that many people’s information diets include little more than superficial takes and outright disinformation. Documentaries and investigative journalism like the Panama Papers, he told ICIJ, break through the media clutter by offering well-substantiated information and “narratives that provide deep and meaningful context.”

His Panama Papers documentary continues to get traction on streaming platforms and is now shown in classrooms — doing its part to help people understand that financial subterfuge and offshore secrecy are driving forces behind a global system that, Winter says, enables corrupt figures such as Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin.

Winter said he often hears from people who have watched the documentary and tell him that they now realize that figures like Putin “aren’t operating within some sort of otherworldly silo. He’s part of the system.”

To change or topple this reality, Winter said, requires reliable information and long-term commitment.

“You don’t change ongoing, systemic corruption overnight with a handful of arrests, or even a lot of arrests,” he said. “You can’t expect instant gratification.”

Investigative reporting and documentary work that seize the popular imagination, Winter said, can help equip ordinary people with the patience and determination to fight the long fight for lasting change.

Panama Papers remix

Last week — the day after Shaolin Temple Defenders performed their Panama Papers song in Switzerland — an international collective of art and music aficionados known as The Asymetrics released an online “mixtape” of Latin, Afro and Caribbean music from the 1960s and ’70s.

Its title: “Panama Papers Vol. 4.”

This is the latest in a continuing series of mixtapes put out by the collective that feature songs ripped from vintage vinyl disks and curated by DJs based in Panama.

One of The Asymetrics’ founders — who goes by his DJ name, Malong — came up with the name for the series. He also curated the collective’s second Panama Papers mixtape, casting off his DJ name and giving himself a new moniker, Samson Fockseca, which sounds a lot like the law firm at the heart of the global financial scandal.

Malong said the motivation for the naming of the mixtape series was more about sly humor than politics. Malong, who is French-born but now lives near the Panama Canal, said that when he mentions living in the country to people in other parts of the world, they will either mention the canal or say: “Panama? Like the Papers?”

The association with secrets and scandal now written into the country’s legacy may be a source of annoyance for some Panamanians. That’s understandable, given that the Panama Papers investigation was as much about offshore clients and operatives in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and more than 200 other countries as it was about the workings of a law firm headquartered in Panama.

It’s the whole system we criticize, not Panama in particular. It could have been in any other place, any nation laundering money. It’s the unfairness of the system that arouses anger. — musician Emmanuel Guérin

For Malong, Panama is more than an infamous offshore haven. It’s “a quiet and beautiful country” where he can step out of his home and trek through a national park and eyeball sloths, parrots and toucans. And its rich musical history also makes it a haven for vinyl collectors like Malong, who haunt second-hand stores and record fairs and drive from village to village knocking on doors and asking occupants if they have vintage vinyl gathering dust in their attics.

Guérin and Ortal, the French funk musicians whose take on the Panama Papers is aggressively political, said their song isn’t a critique of Panama itself.

“I don’t think the Panamanian people should be held responsible for this at all,” Guérin said. “It’s the whole system we criticize, not Panama in particular. It could have been in any other place, any nation laundering money. It’s the unfairness of the system that arouses anger.”