Since Vladimir Putin rose to power in 2000, his oligarch allies have found few barriers to luxury, snapping up yachts, jets, villas and other assets, with plenty of professional help along the way.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine changed all that.

Governments have sanctioned members of President Putin’s inner circle, alleging their wealth came on the back of insider deals for sovereign assets. Authorities have seized yachts in docks and planes in hangars.

But targeting owners is one thing. Identifying the enablers – the elite professionals who help oligarchs buy, conceal and maintain the assets – is another.

Leaked records show for each luxury plaything they bought, Russians now under sanctions relied on the services of a small army of professionals in Europe, Asia and North America: attorneys to write contracts, brokers to sell insurance, bankers to move the money, accountants, ship builders to hand over the keys – all without asking too many questions about where the money came from.

The Western enablers say they broke no laws in helping oligarchs. Yet, experts say, they do have a choice and every opportunity to identify their customer and decline the business.

“Without Wall St, London, Zurich bankers, lawyers, property dealers, yacht brokers, and other financial consultants, the oligarchs could not have secretly and safely moved vast funds into Western markets,” Frank Vogl, a co-founder of Transparency International, told ICIJ in an email. “Everyone in business has a choice — to do the right thing, serve the core public interest and act with integrity, or act in the shadows to secure more and more cash.”

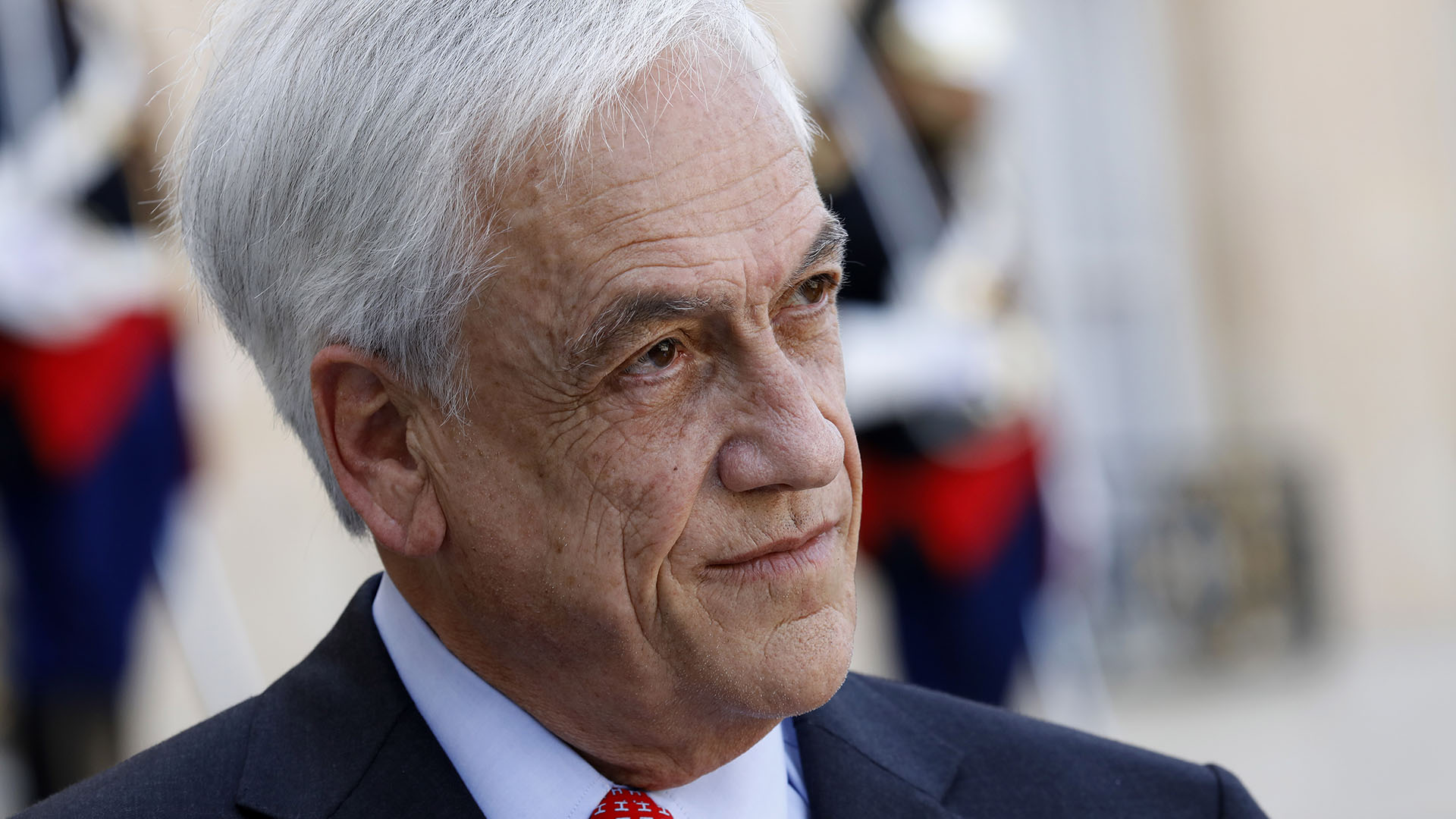

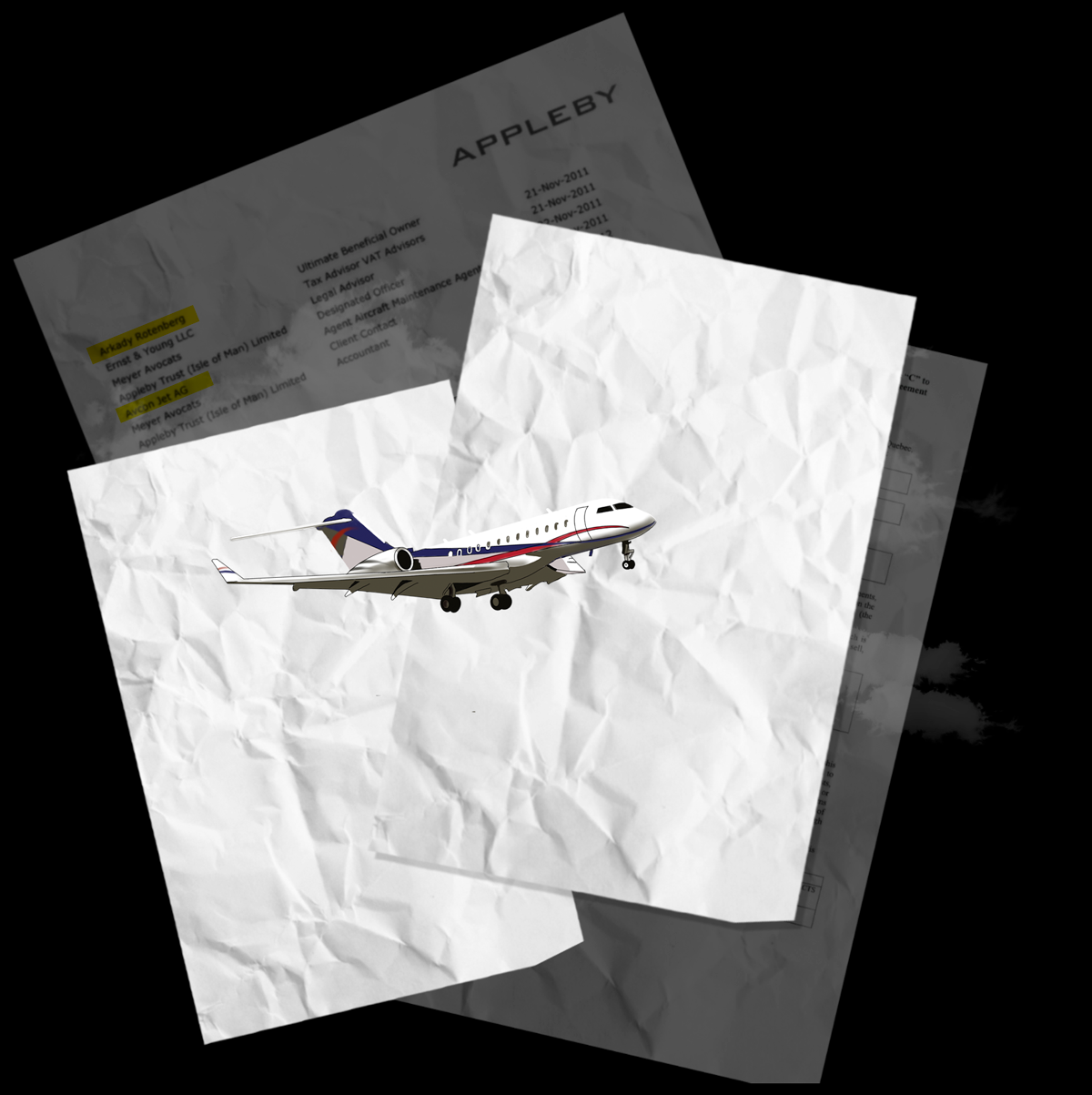

In 2011, billionaire Arkady Rotenberg, Putin’s judo partner, bought a jet.

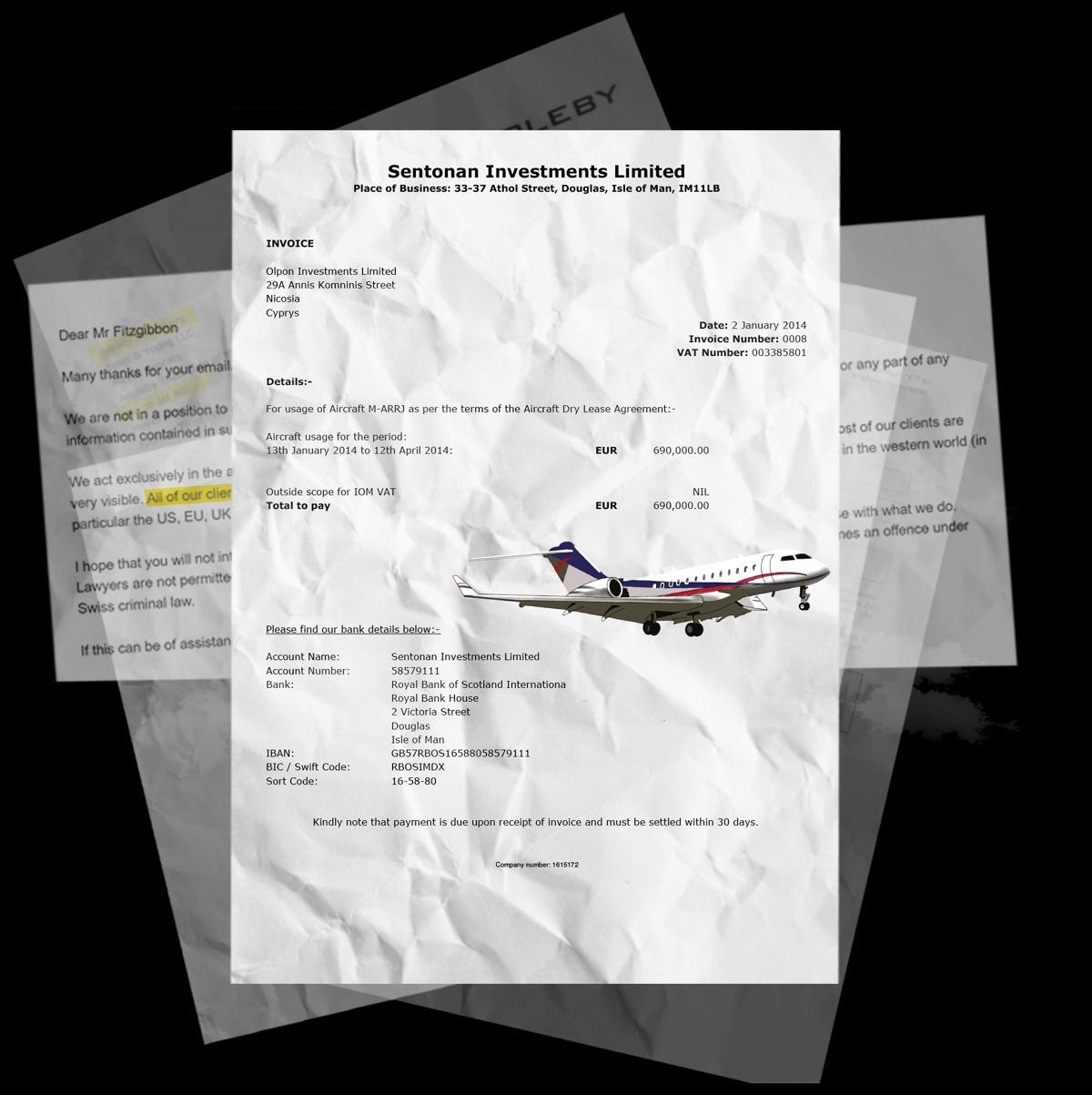

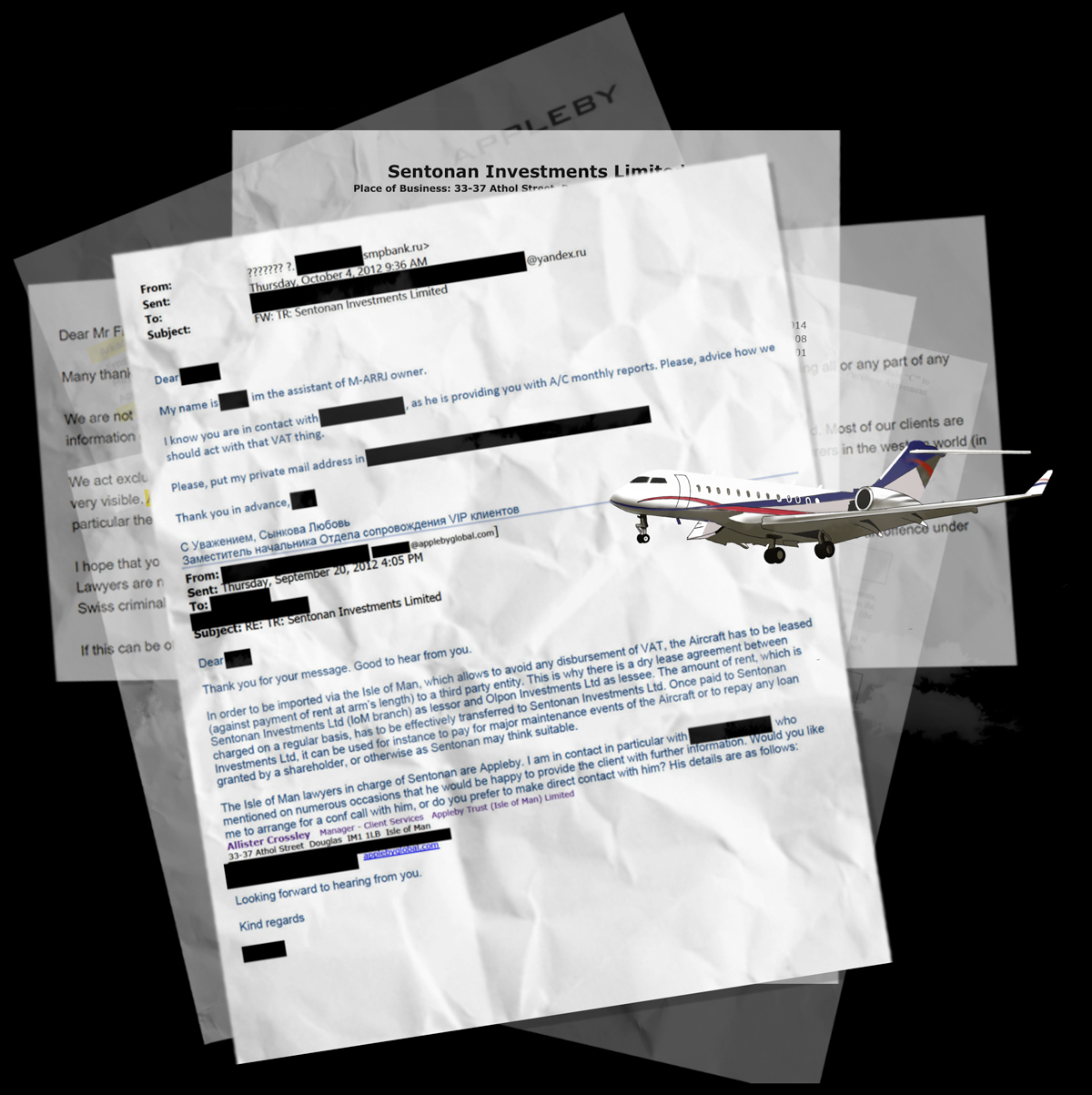

He bought it through a secretive shell company in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) set up by Appleby, the offshore law firm at the center of ICIJ’s 2017 Paradise Papers investigation.

Arkady’s brother, Boris, also scooped up a jet through a similar arrangement.

Bombardier in Canada sold the jet to Rotenberg’s offshore company. Ernst & Young, also known as EY, advised on taxes. Swiss attorneys, Meyer Avocats, offered legal advice, and Avcon Jet in Austria managed the jet’s upkeep.

Avcon Jet and EY didn’t reply to our questions. Appleby didn’t comment when we first reported on the jet.

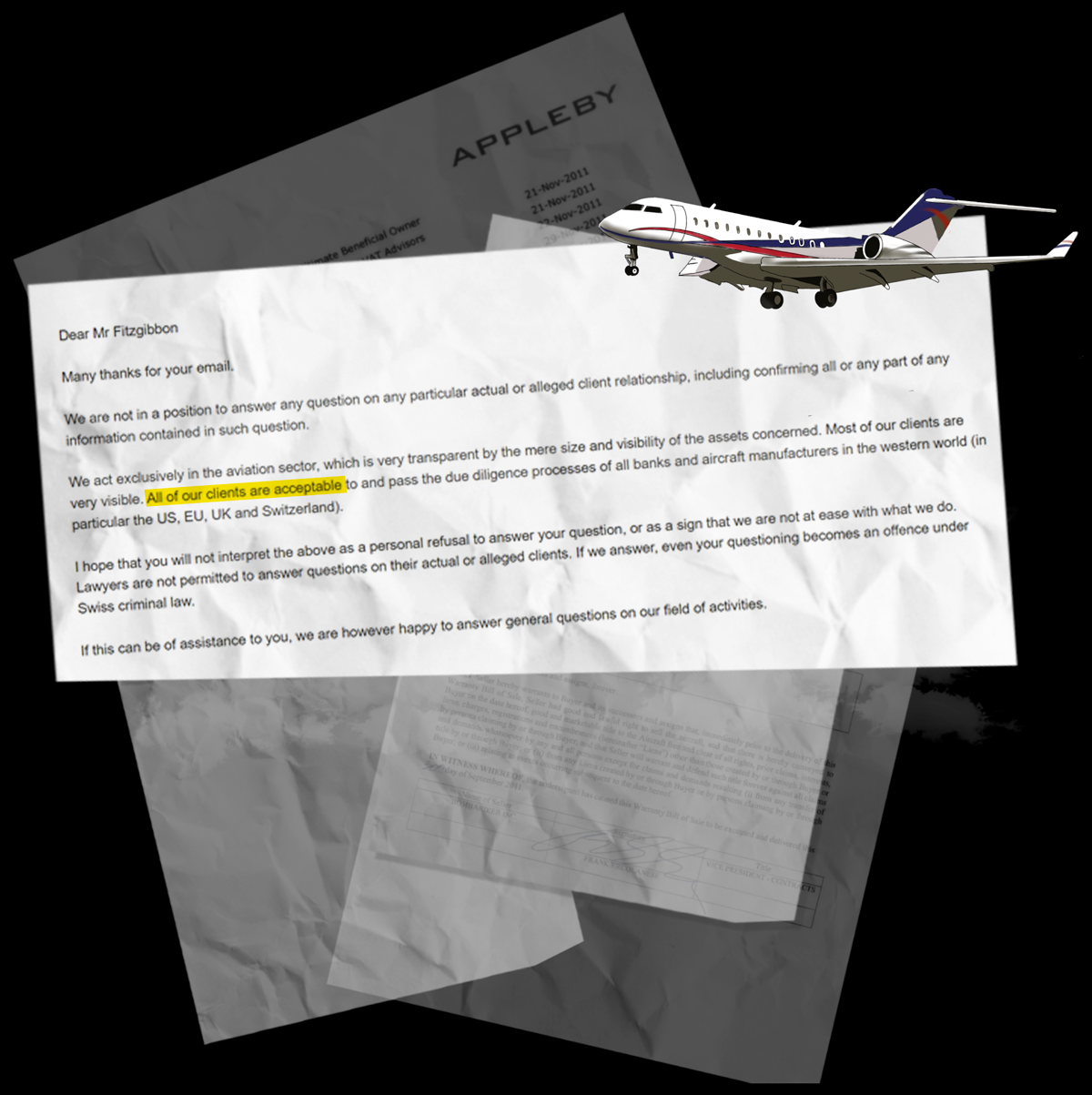

Meyer Avocats, in Switzerland, sent us this reply when we asked what due diligence they performed before working for Rotenberg.

Royal Bank of Scotland’s Isle of Man branch opened an account for Rotenberg’s company. The bank said it couldn’t comment on customers.

Rotenberg used a leasing arrangement that helped him avoid taxes on the Isle of Man.

Public records show Rotenberg’s shell company owned the jet until 2016. Records show that a church in Fort Worth, Texas, bought the jet in 2017.

Last month, the U.S. sanctioned Arkady and Boris Rotenberg, alleging that they are among “Putin’s cronies.” The brothers have denied benefiting financially from their friendship with Russia’s president.

Many sanctioned Russian billionaires came from humble beginnings. One sold used rugs and resold theater tickets. Others, like Gennady Timchenko, reportedly studied espionage alongside Vladimir Putin decades ago at KGB training school. All have since gone on to amass eye-watering wealth.

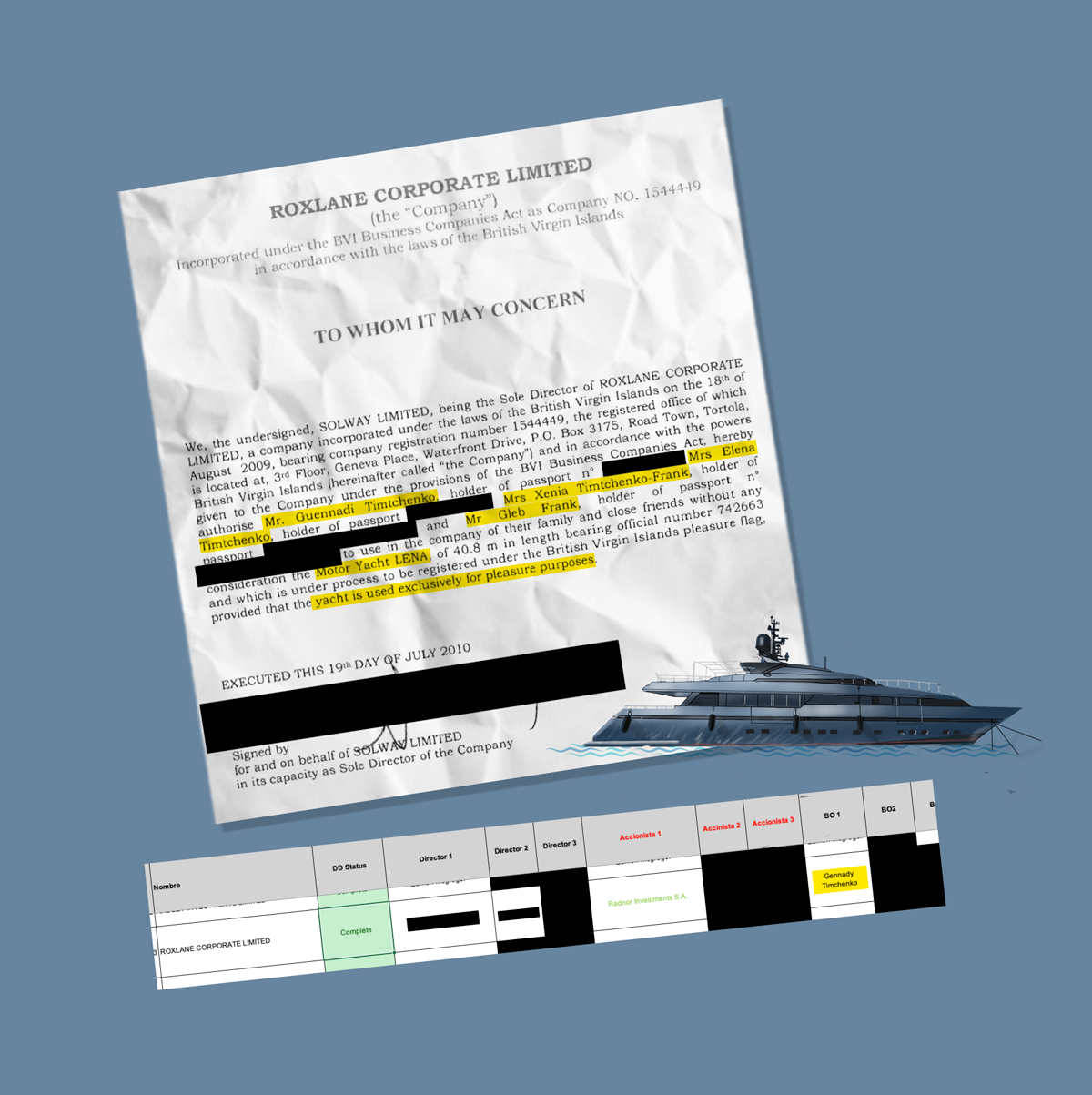

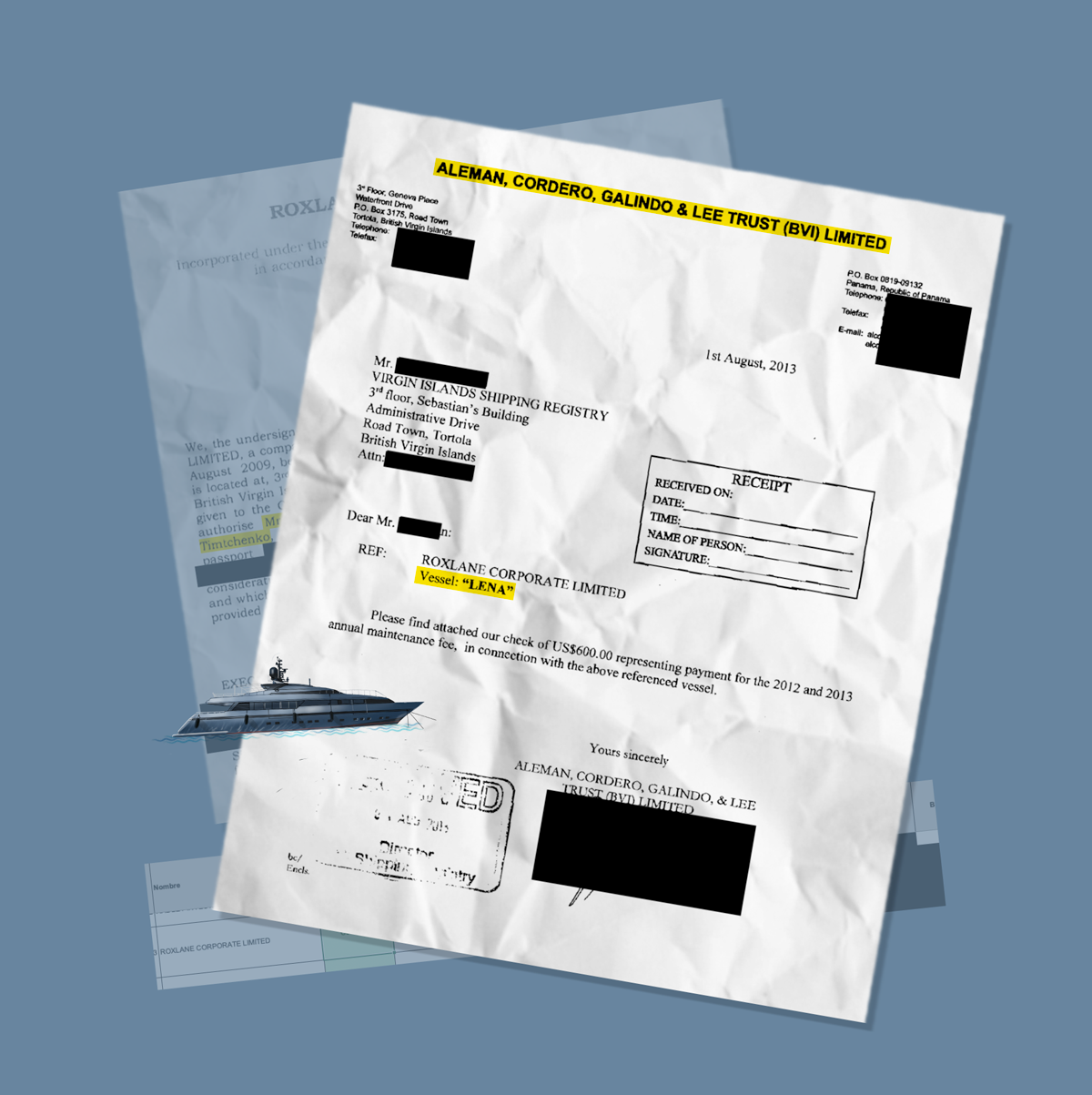

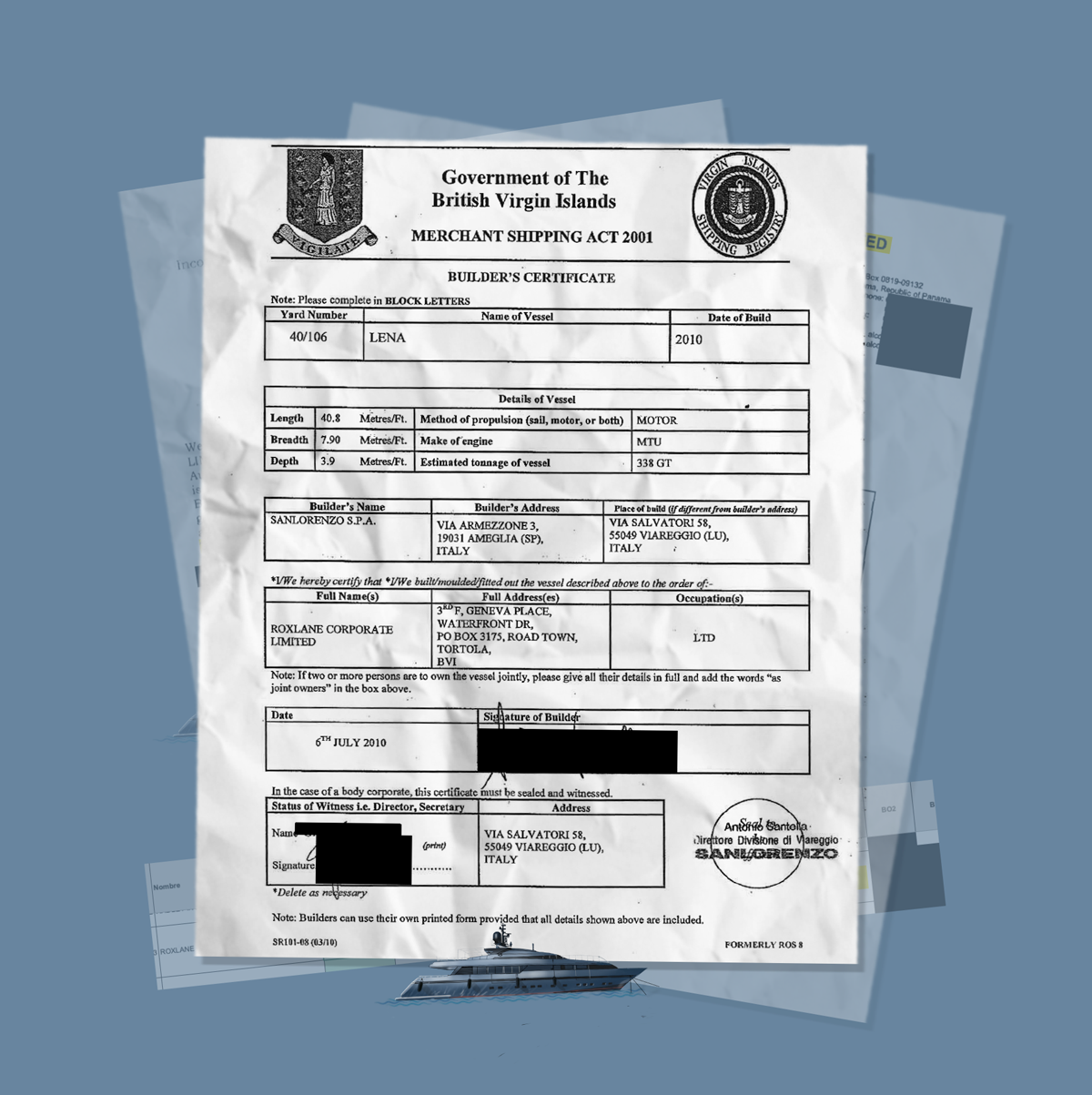

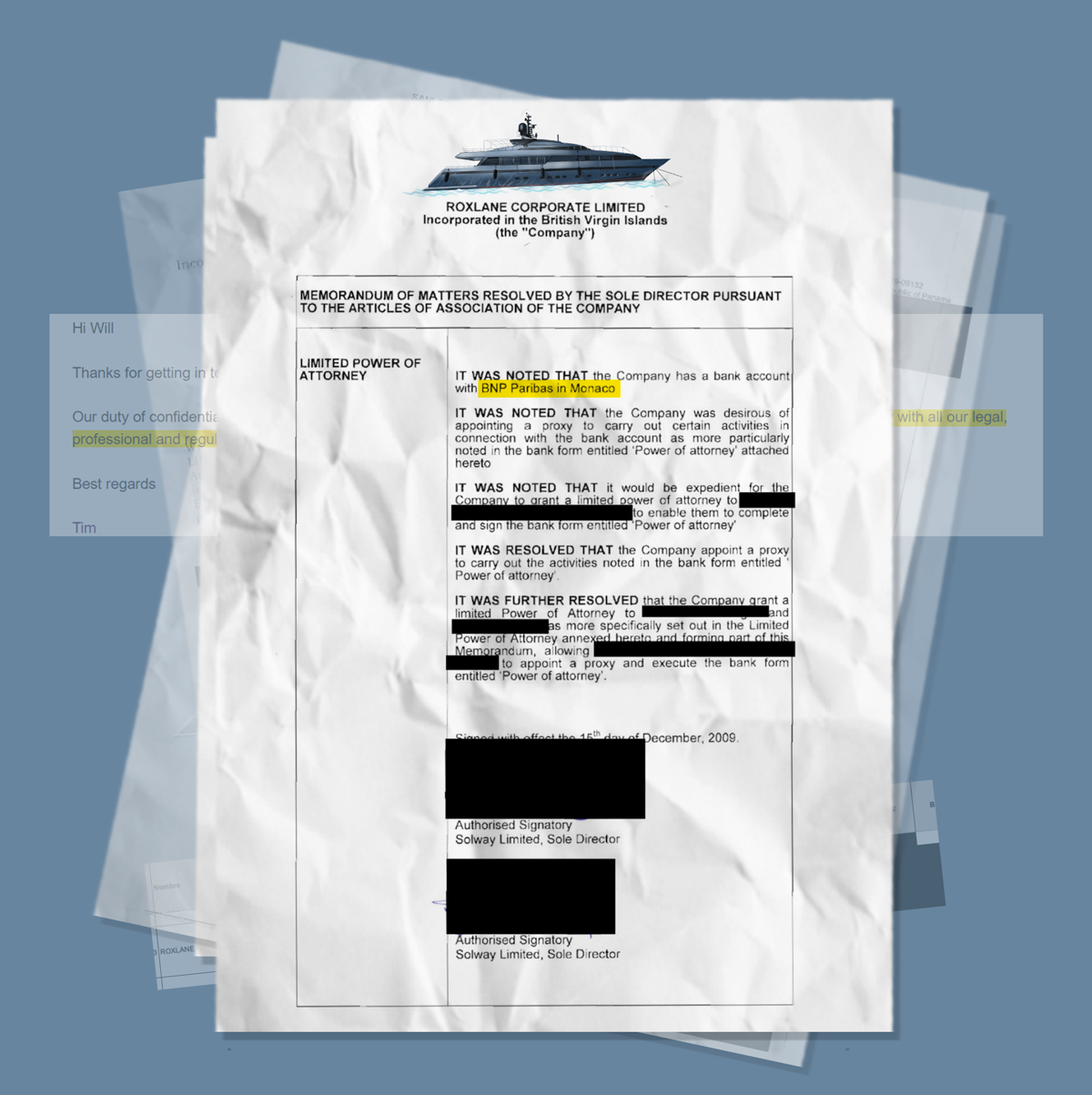

In 2009, Timchenko, a Russian gas and petrochemical billionaire, used a secretive offshore company to buy the Lena yacht for more than $18 million.

Timchenko’s wife, daughter and son-in-law, Gleb Frank, were all authorized to use the yacht, records show. All three were sanctioned last month by the U.S. Treasury.

The U.S. sanctioned Timchenko in 2014 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Aleman, Cordero, Galindo & Lee, an offshore law firm with operations in the BVI, helped Timchenko set up a shell company in the Caribbean.

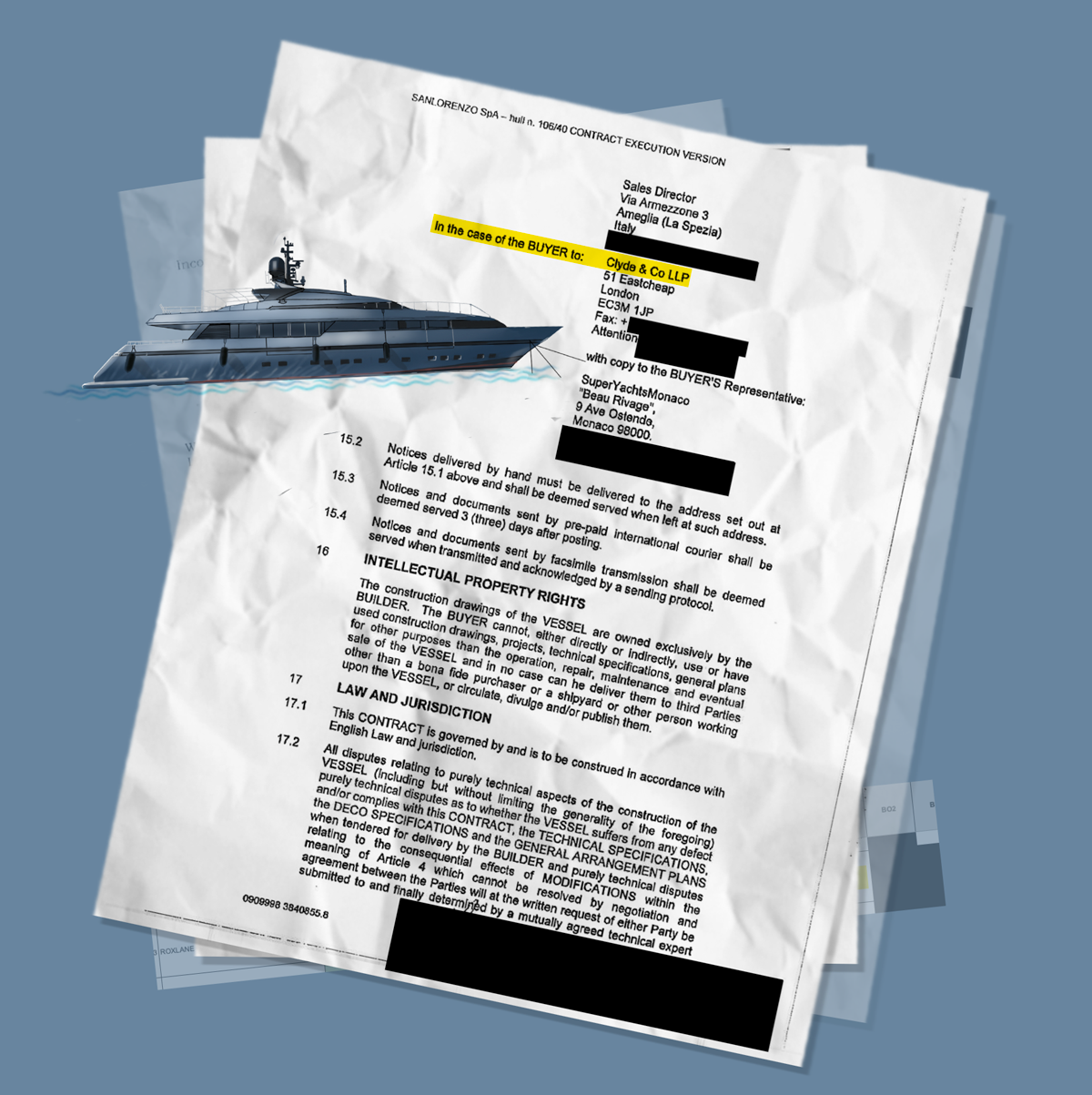

Italian shipbuilder Sanlorenzo SPA built the 130-foot yacht, signing a contract with the oligarch’s offshore company.

Sanlorenzo told ICIJ it applies strict due diligence and the BVI company and its owner were not sanctioned at the time of purchase.

Representing Timchenko’s offshore company were two law firms: London’s Clyde & Co. and Monaco-based Moores Rowland.

Clyde & Co told us it complies with its obligations. Moores Rowland previously said it follows all laws and regulations and accepts clients after “rigorous” checks.

Timchenko also set up his offshore company with a bank account at BNP Paribas in Monaco.

Last month, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned the yacht Lena, adding it to a list of official sanctions.

Timchenko has denied that President Putin is connected to his businesses. He previously said he has always acted lawfully. In March, the Italian government seized the Lena, one of at least nine luxury yachts impounded around the world since Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine.

“The enablers are not just those dealing in finance,” Vogl said, adding that others “used their influence in return for handsome fees, to try to polish the reputations of oligarchs who in so many cases have utterly failed to disclose how they made their fortunes and how they continue to acquire massive wealth.”

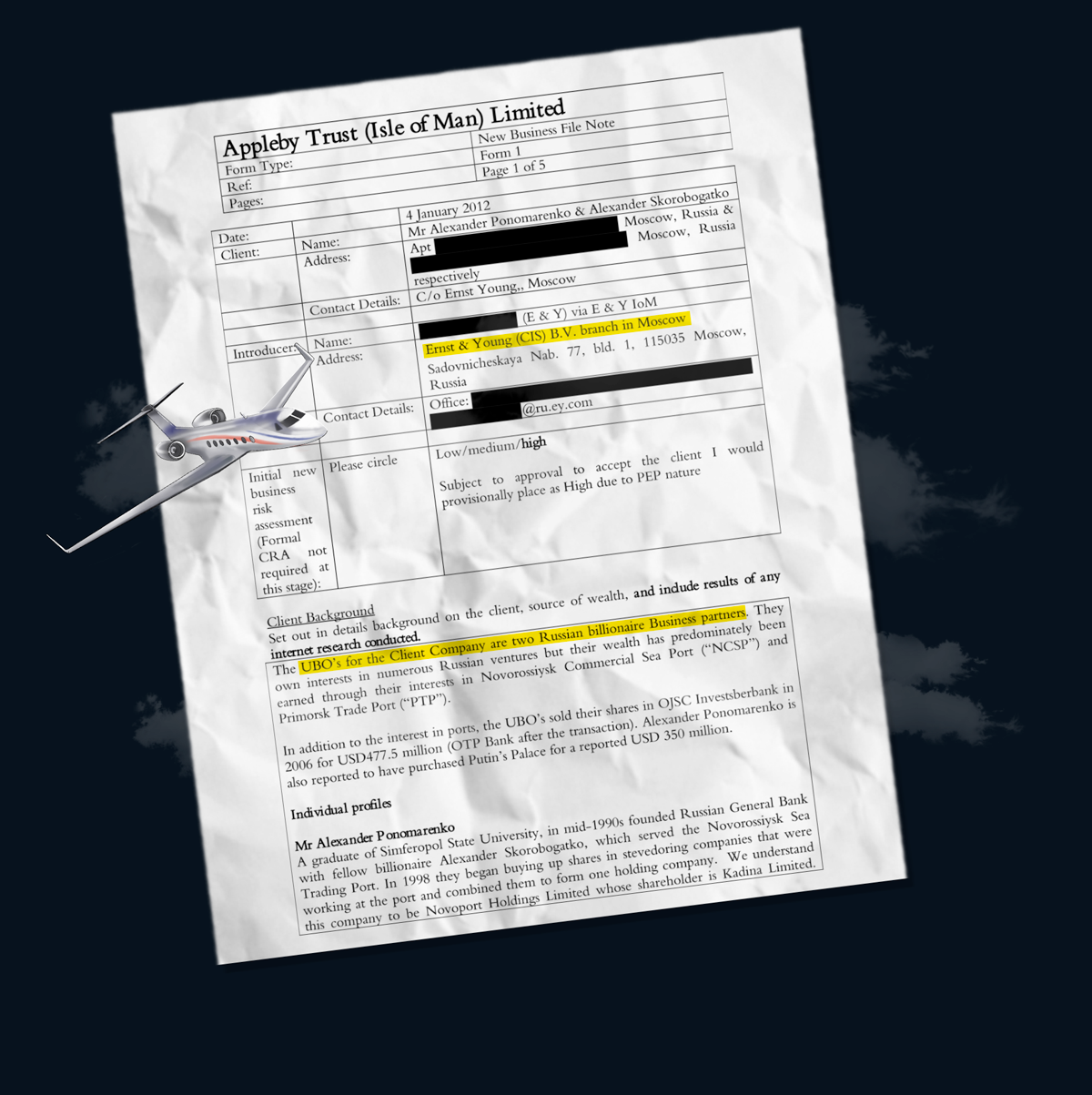

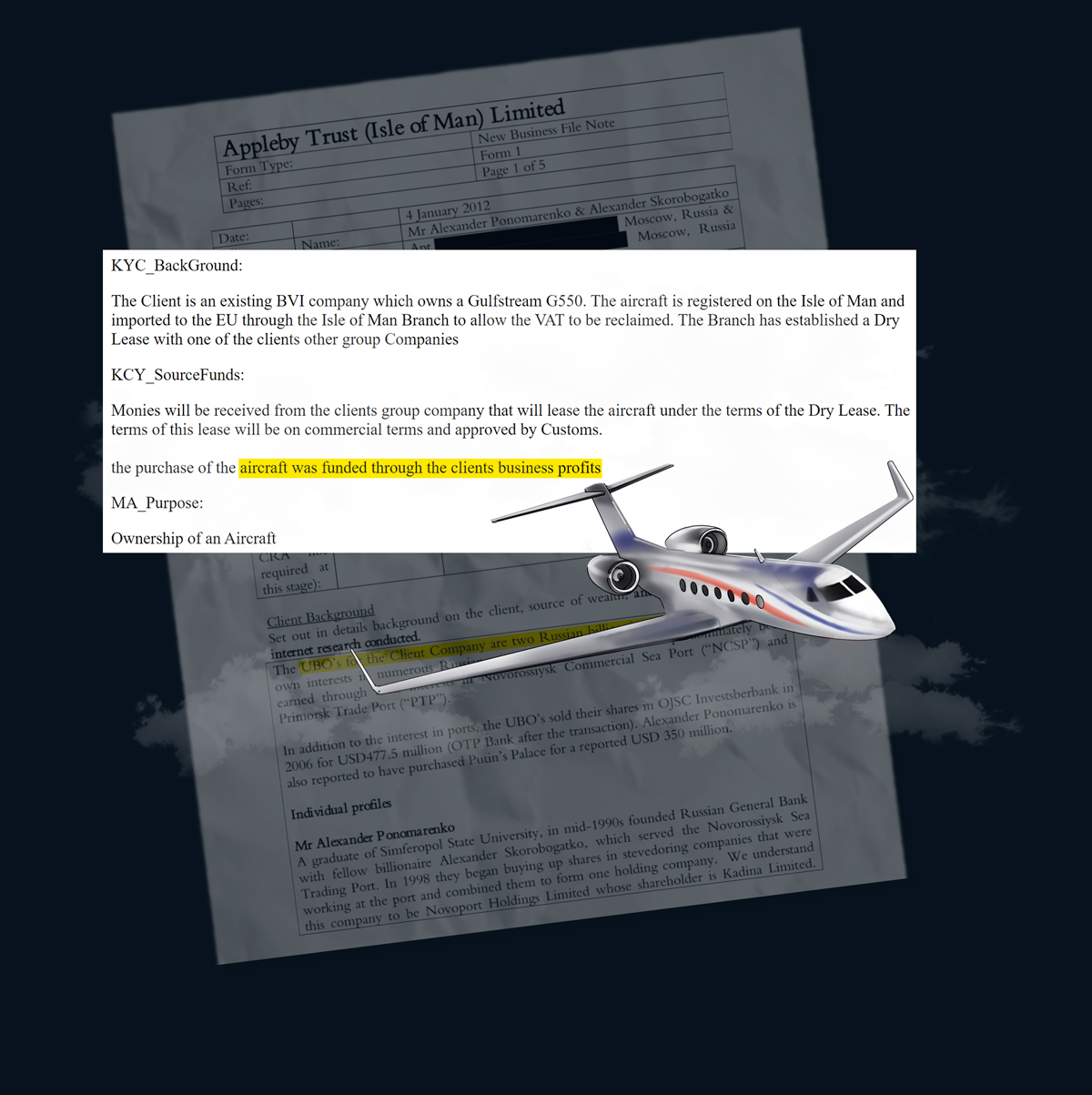

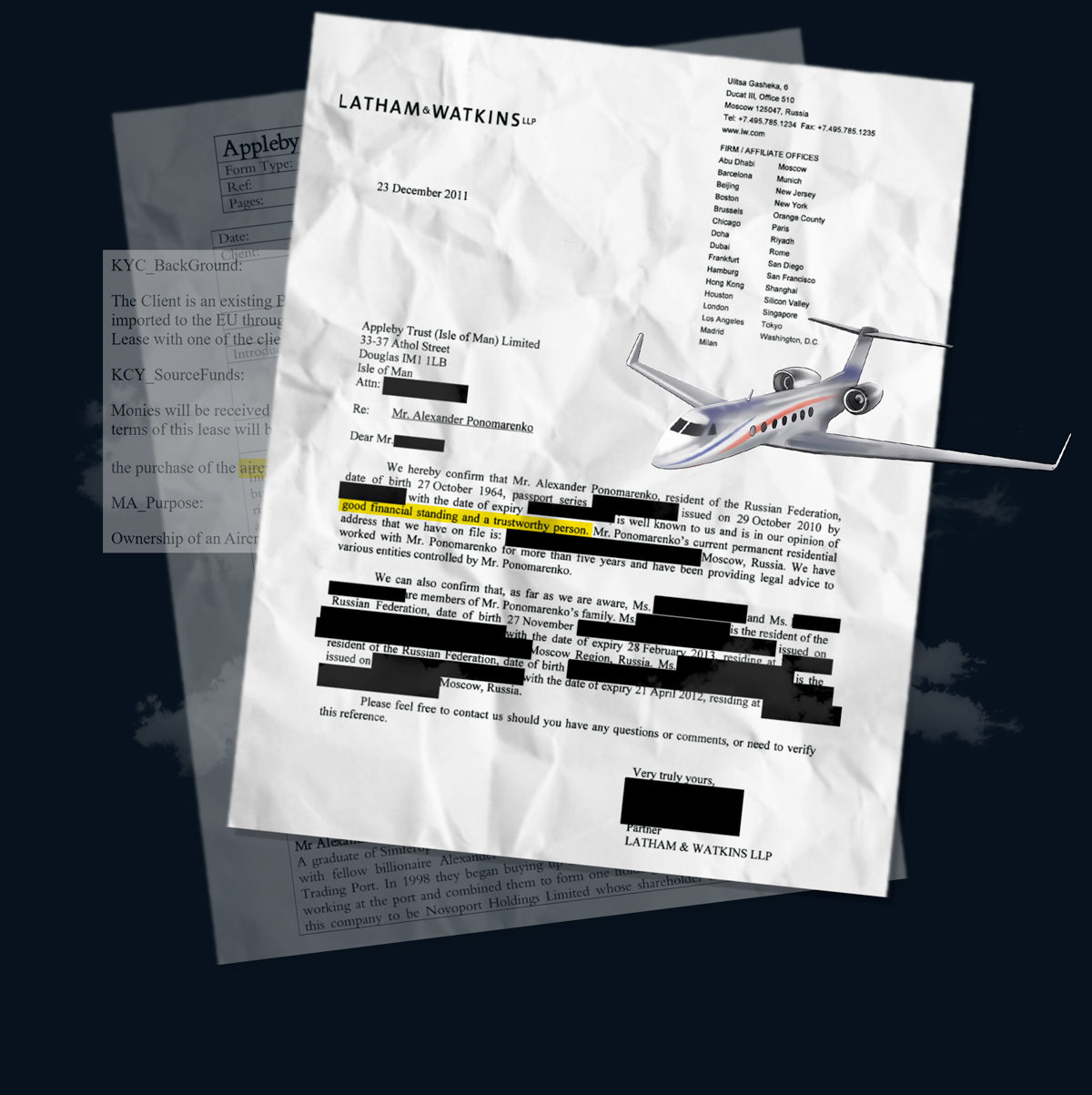

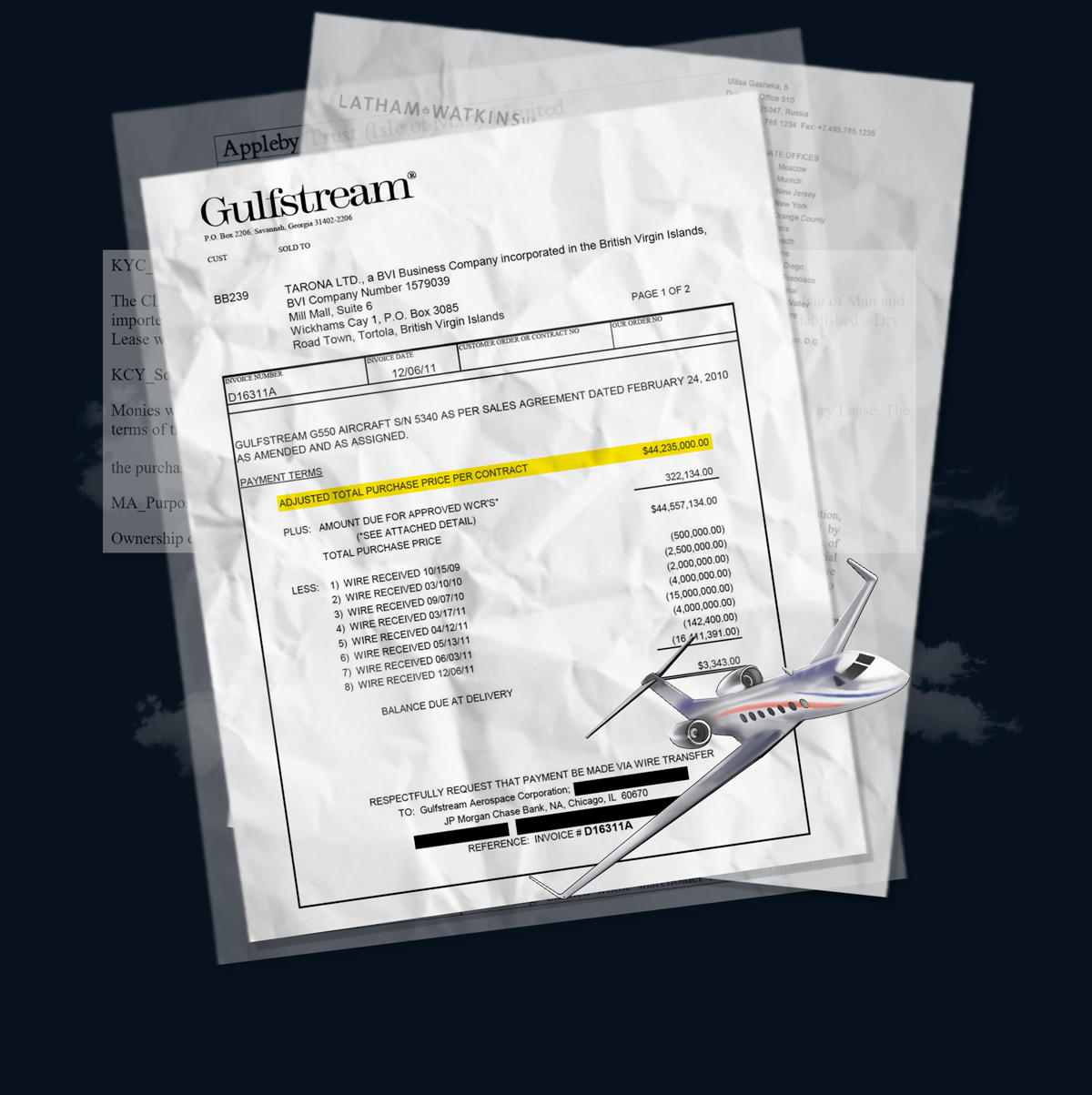

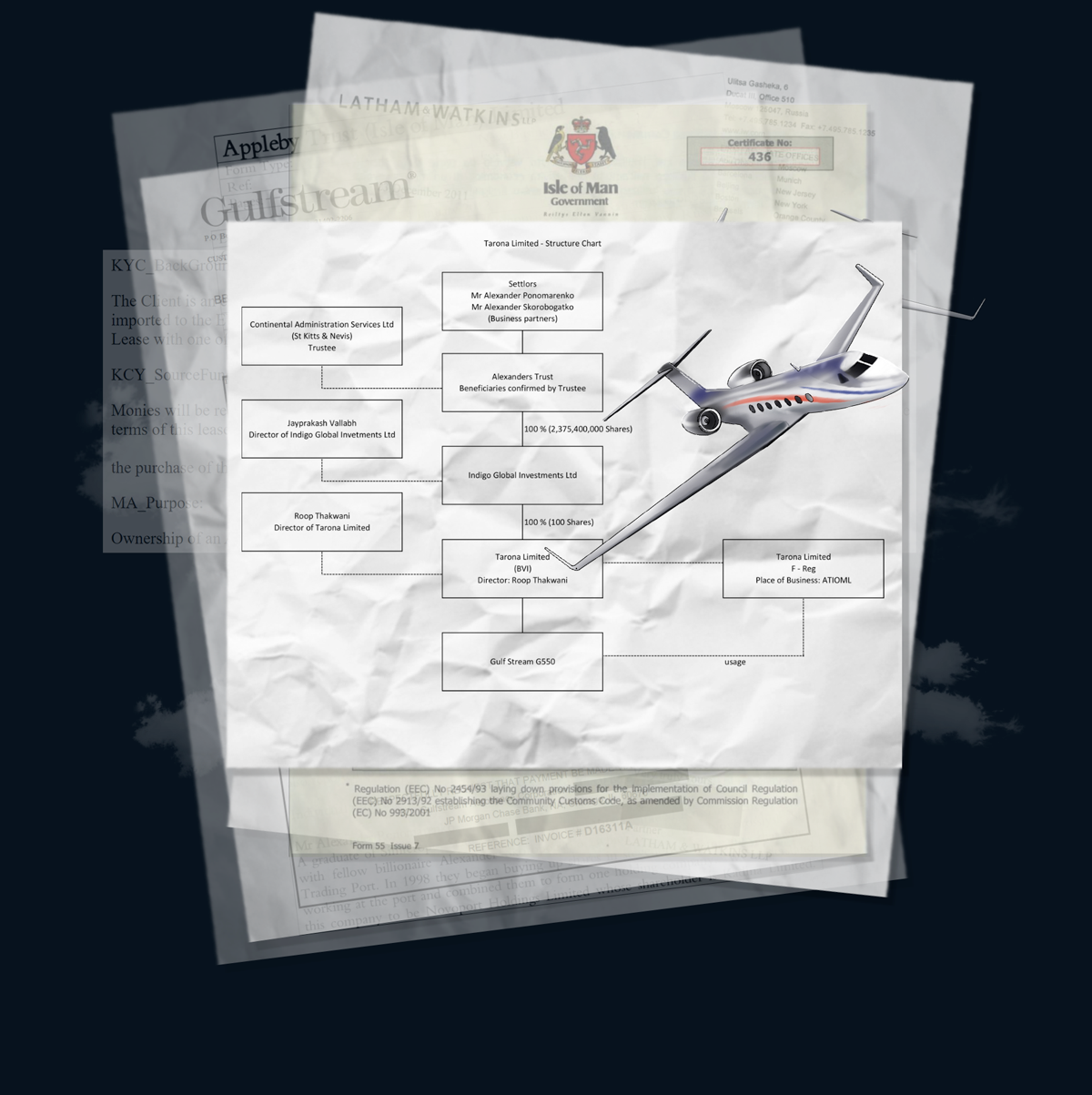

In 2011, the Moscow office of accounting firm EY helped now-sanctioned billionaire Alexander Ponomarenko set up an offshore company with a business partner and former politician, Alexander Skorobogatko, to buy a $44.5 million Gulfstream jet.

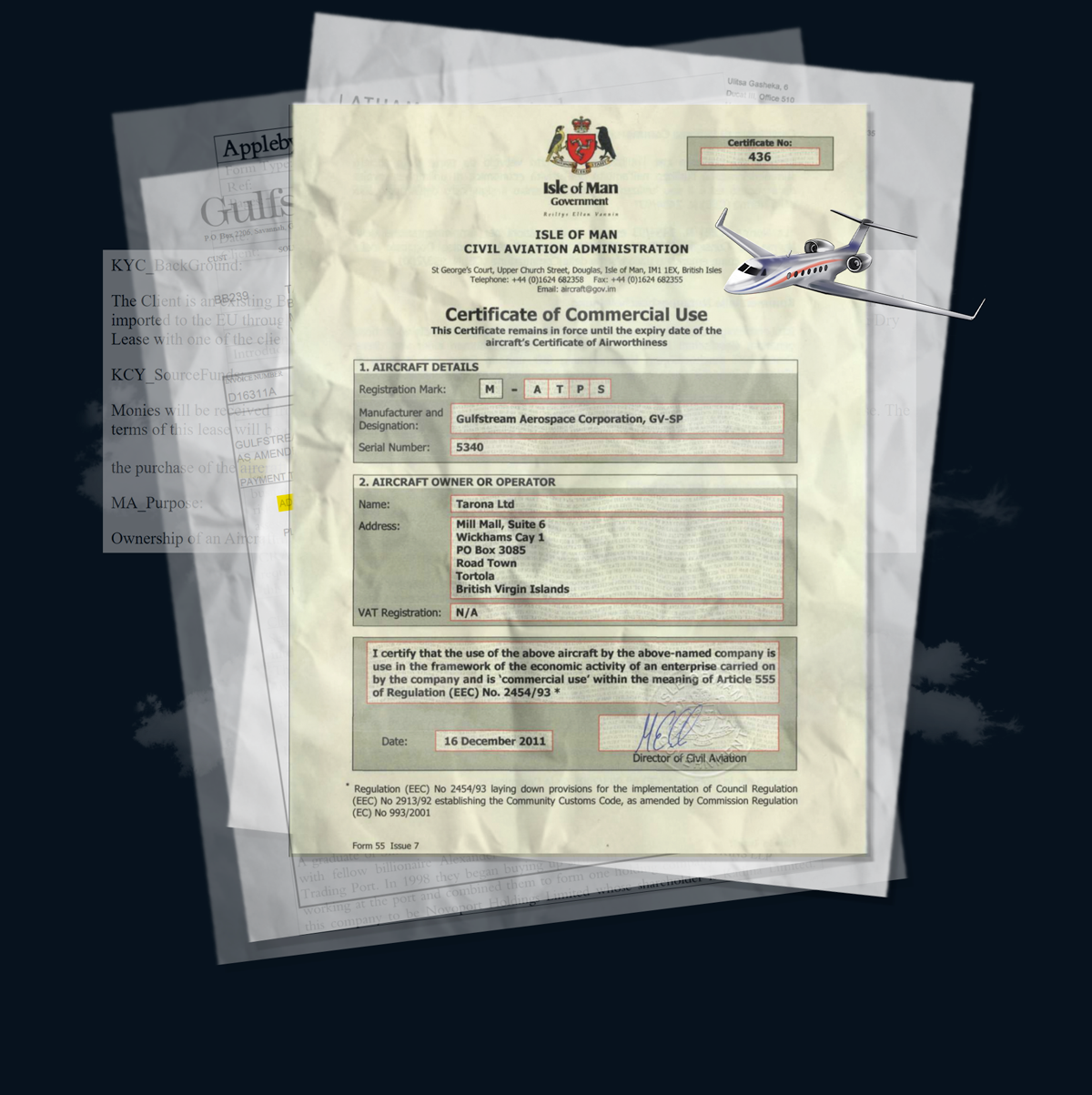

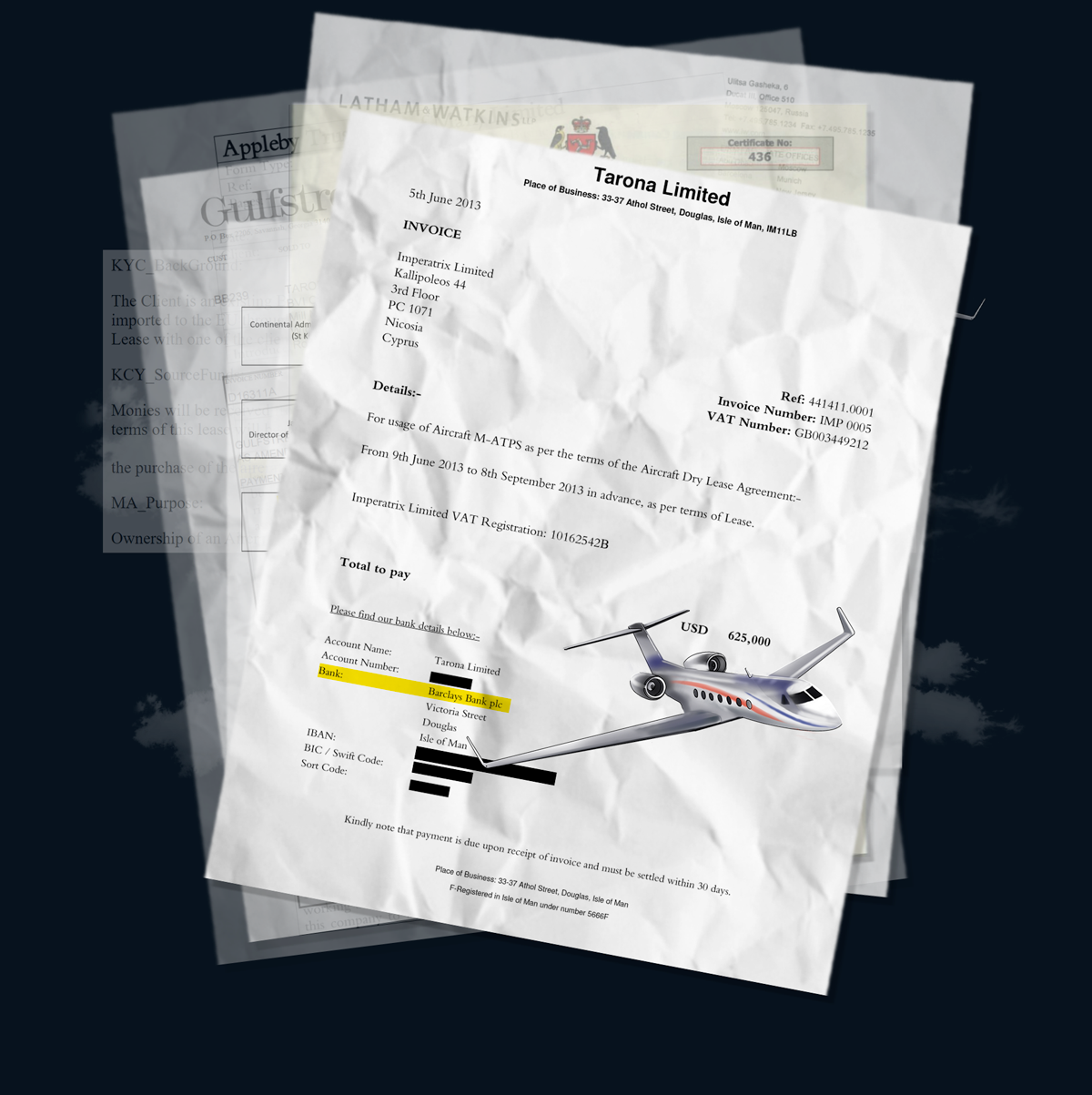

Ponomarenko’s offshore company, Tarona Ltd., hired Appleby in the Isle of Man. The purchase of the jet was “funded through… business profits,” Appleby wrote.

The Moscow office of American law firm Latham & Watkins provided a personal reference for Ponomarenko.

Gulfstream Aerospace Corp., based in Savannah, Georgia, signed a sales contract with Tarona Ltd.

Government agencies on the Isle of Man helped Ponomarenko’s company, including providing certificates of registration.

Increasing the secrecy, Ponomarenko’s company was owned by a trust and on paper controlled from St. Kitts and Nevis, a tax haven. Ponomarenko and Skorobogatko’s families were trust beneficiaries.

The BVI company, Tarona Ltd., opened an account with Barclays Bank on the Isle of Man.

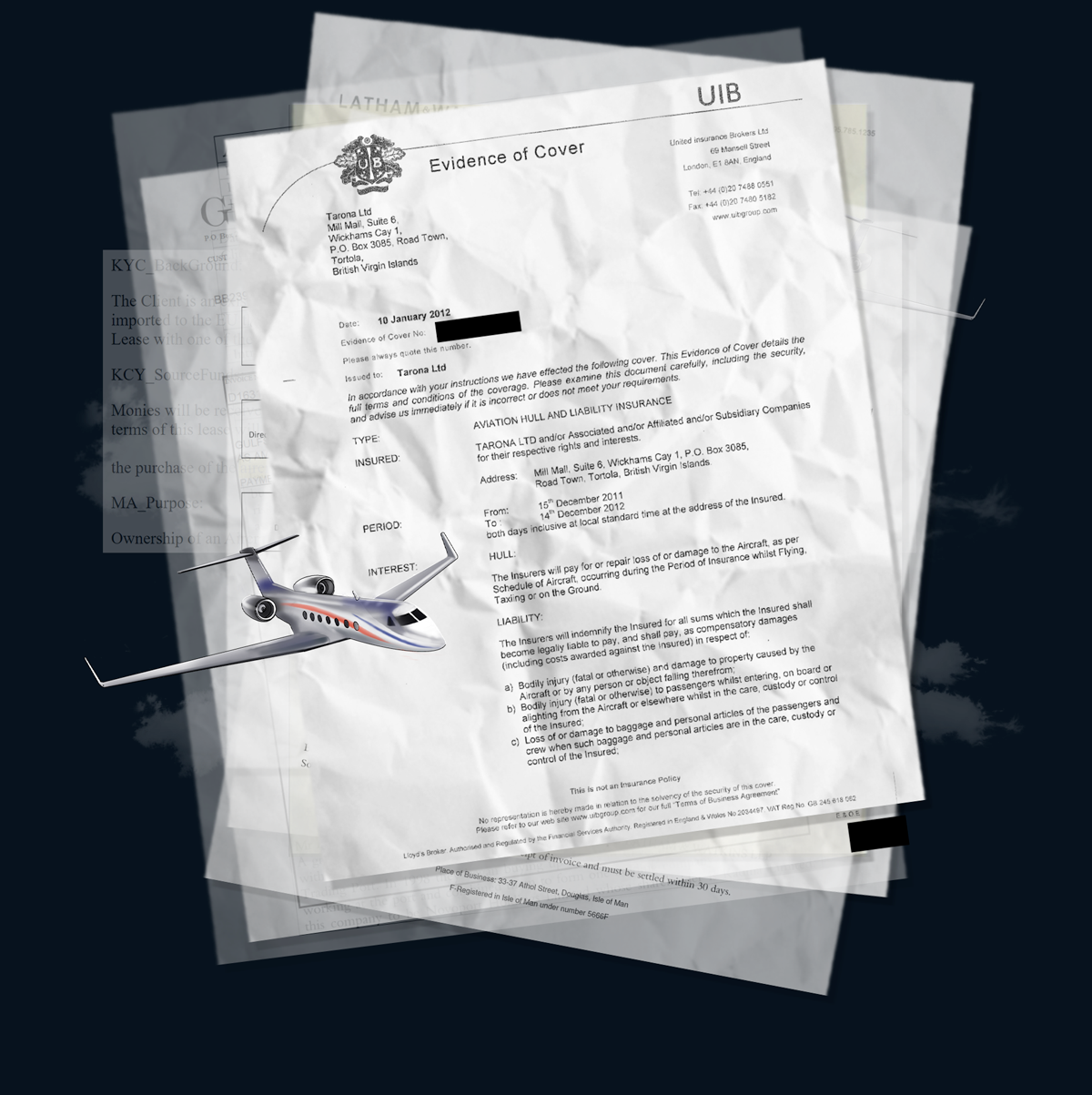

A London-based company, United Insurance Brokers, insured Ponomarenko’s company and jet.

In this case, records show at least 10 Western enablers helped Ponomarenko acquire and enjoy his luxury asset. None replied to ICIJ’s requests for comment.

Ponomarenko has previously rejected reports of financial ties to President Putin.

The United Kingdom, Switzerland and Singapore are among countries that have condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and sanctioned state-owned companies, including Russia’s largest gas company, Gazprom. For years, leaked records show, those same governments were home to Gazprom investments and shell companies and pit stops for suspicious transactions.

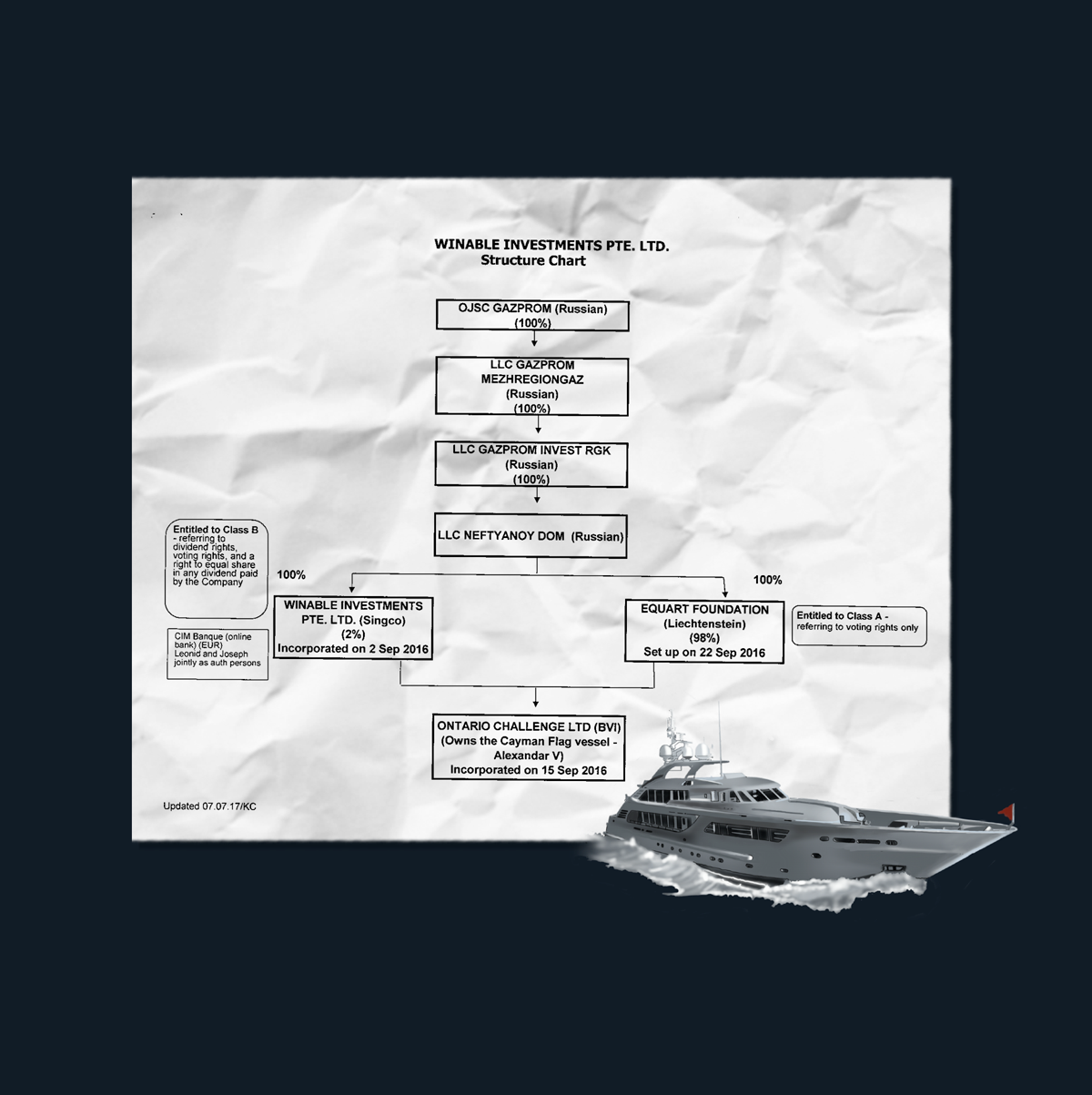

In 2010, Russian gas company Gazprom bought a 157-foot yacht, Alexandar V, for more than $25 million.

The yacht, with a jacuzzi, was for Gazprom guests and staff, records show.

In 2016, Gazprom added “extra asset protection of the vessel.” It complicated the ownership structure with three new shell companies in infamous tax havens-- Singapore, the BVI and Liechtenstein.

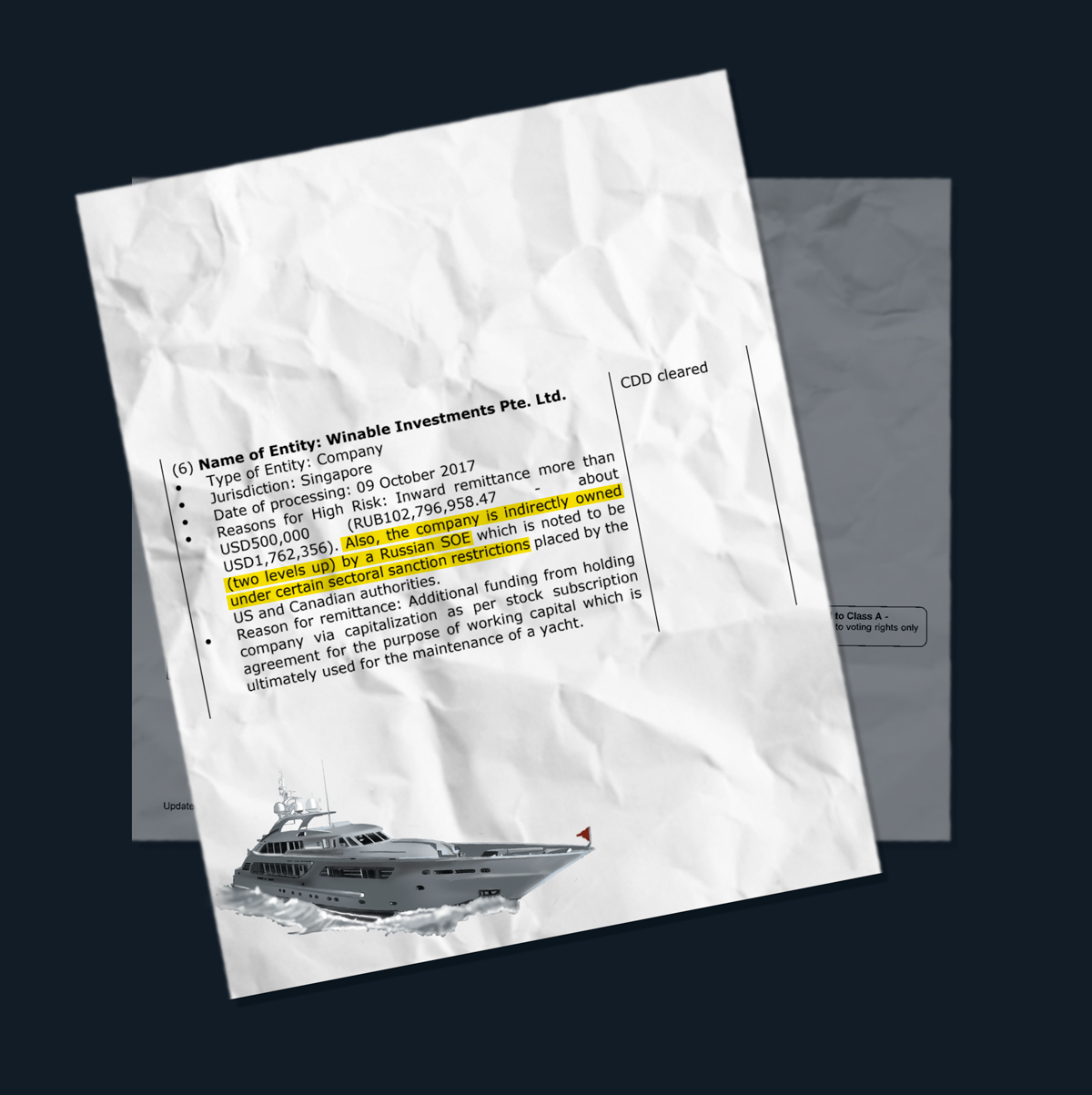

Enablers, including Asiaciti, knew Gazprom was under sanctions when providing services for the yacht, records show.

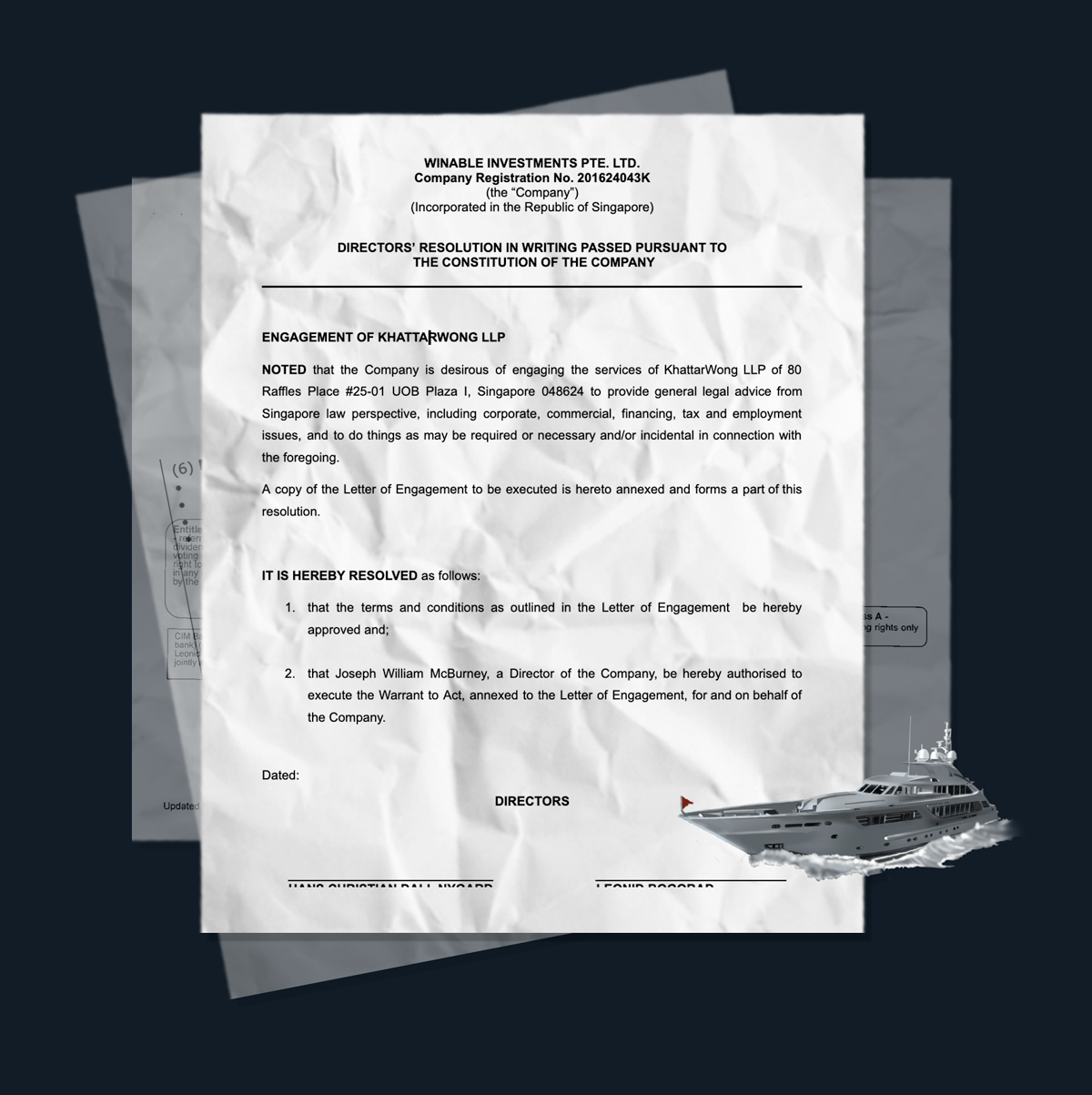

The auditors of one shell company that owned the yacht was Robert Yam & Co. in Singapore, which signed a non-disclosure agreement about its work. A major law firm, KhattarWong LLP, provided advice to the shell company. It told ICIJ its “professional duties” prevented it from answering questions.

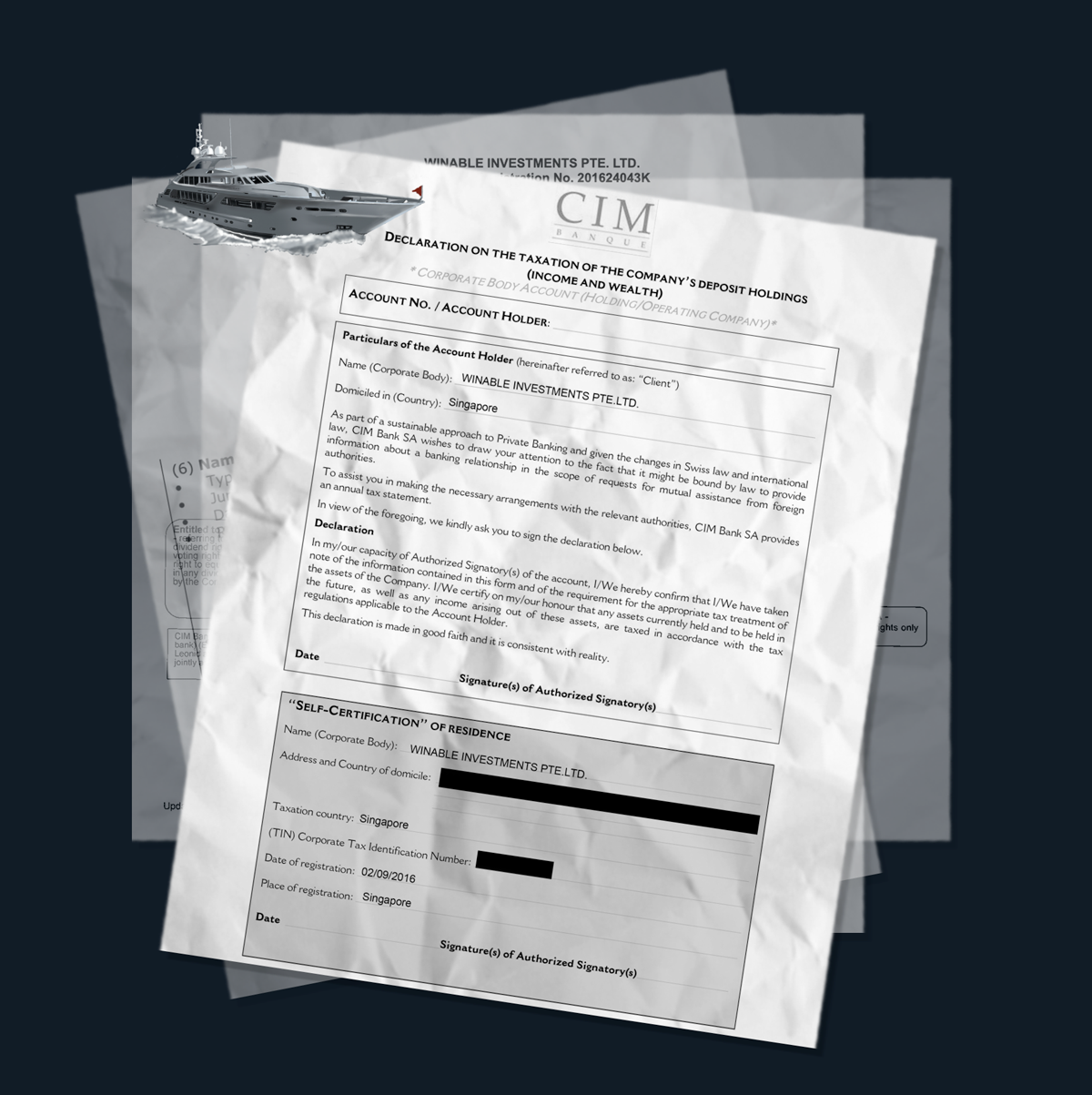

One Singaporean company behind the yacht, Winable Investments Pte Ltd. opened a bank account in Switzerland with CIM Bank.

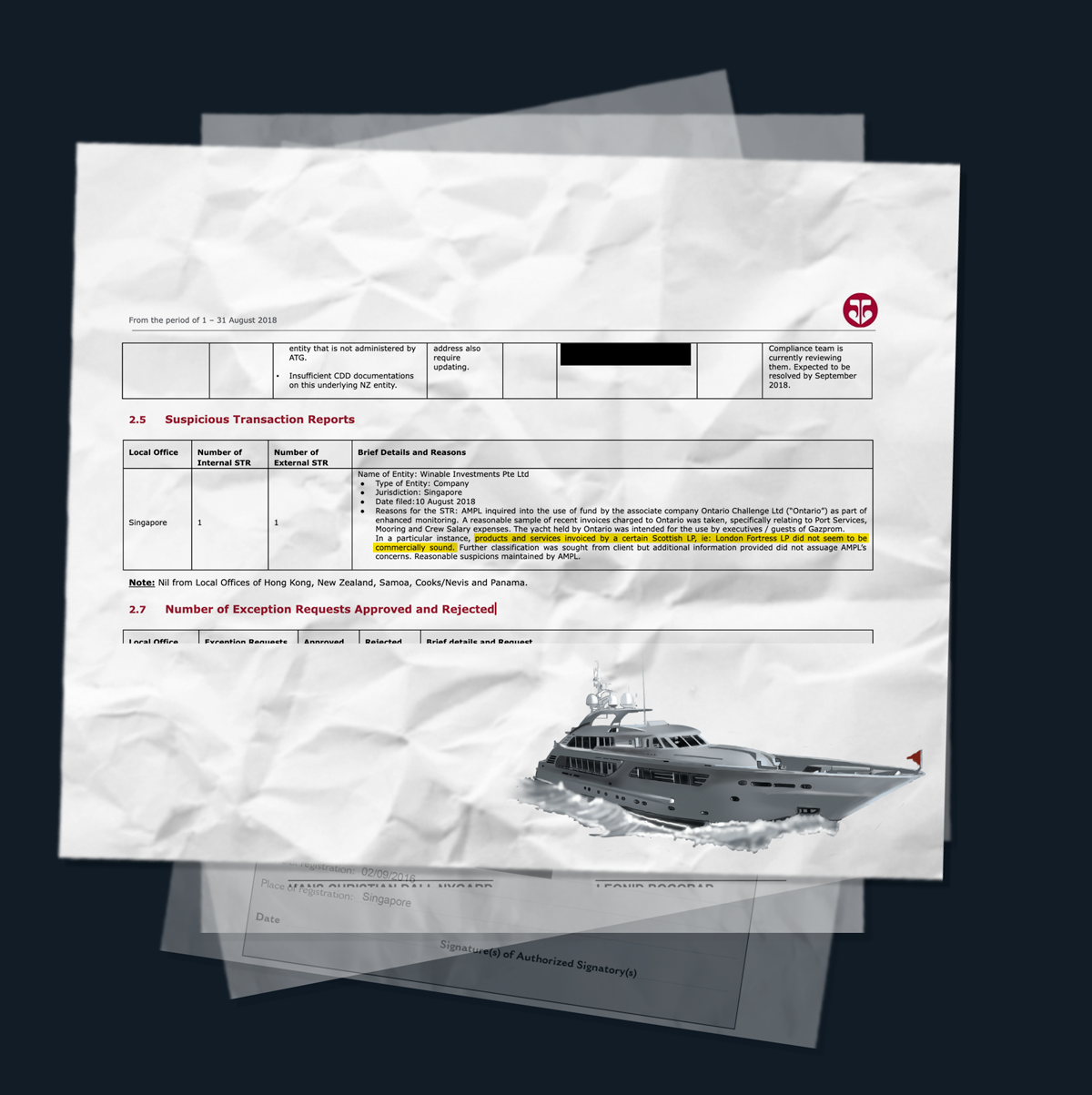

In 2018, Asiaciti reported to Singaporean authorities that it was suspicious about Gazprom’s company paying invoices that “did not seem to be commercially sound” to a shell company in Scotland.

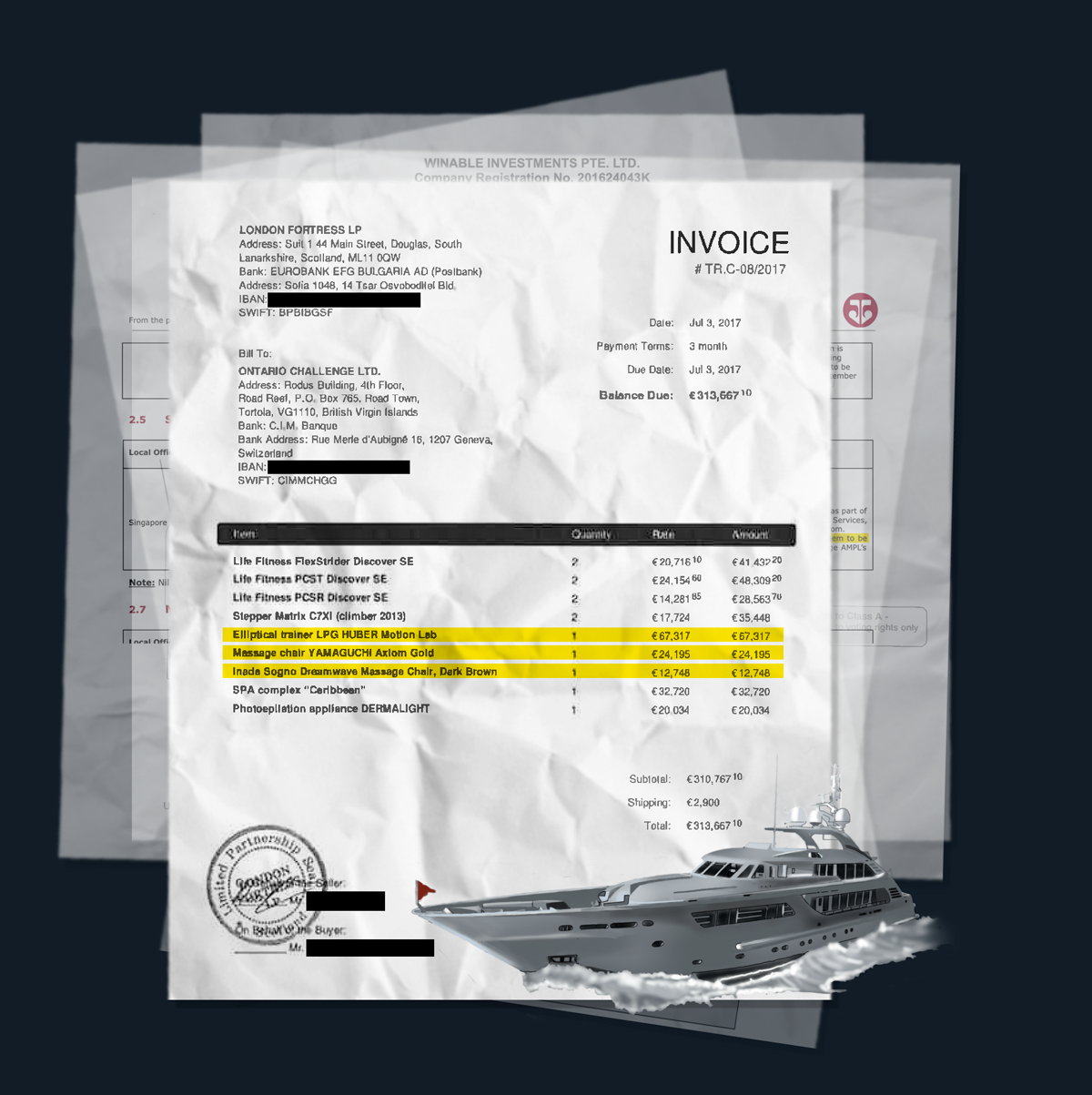

The Scottish company, which shared an office with dozens of other companies, sits opposite a pub in a small town 30 miles from Glasgow. The company had a bank account in Bulgaria.

Pandora Papers records show Gazprom paid the company to install an elliptical trainer and massage chair, among other things.

The yacht was last seen earlier this year docked in Italy.

ICIJ asked Gazprom and its other enablers to comment on but received no reply.

Leaked records show, however, that the Russian company’s enablers had questions of their own. “Additional information provided did not assuage…concerns,” AsiaCiti’s employees wrote in 2018.

“Reasonable suspicions maintained.”