At 5:37 p.m. on April 22, 2011, from a seaside launch pad in Latin America, a hulking satellite rose into the sky and came to rest over the 33rd meridian east, above northern Tanzania.

The New Dawn Satellite was proudly African – partly funded by local investors and promoted as a way for African schoolchildren, nurses, civil servants and businesses to access world-class internet and mobile phone networks.

But if its purpose was to promote African development, its tax strategy did exactly the opposite.

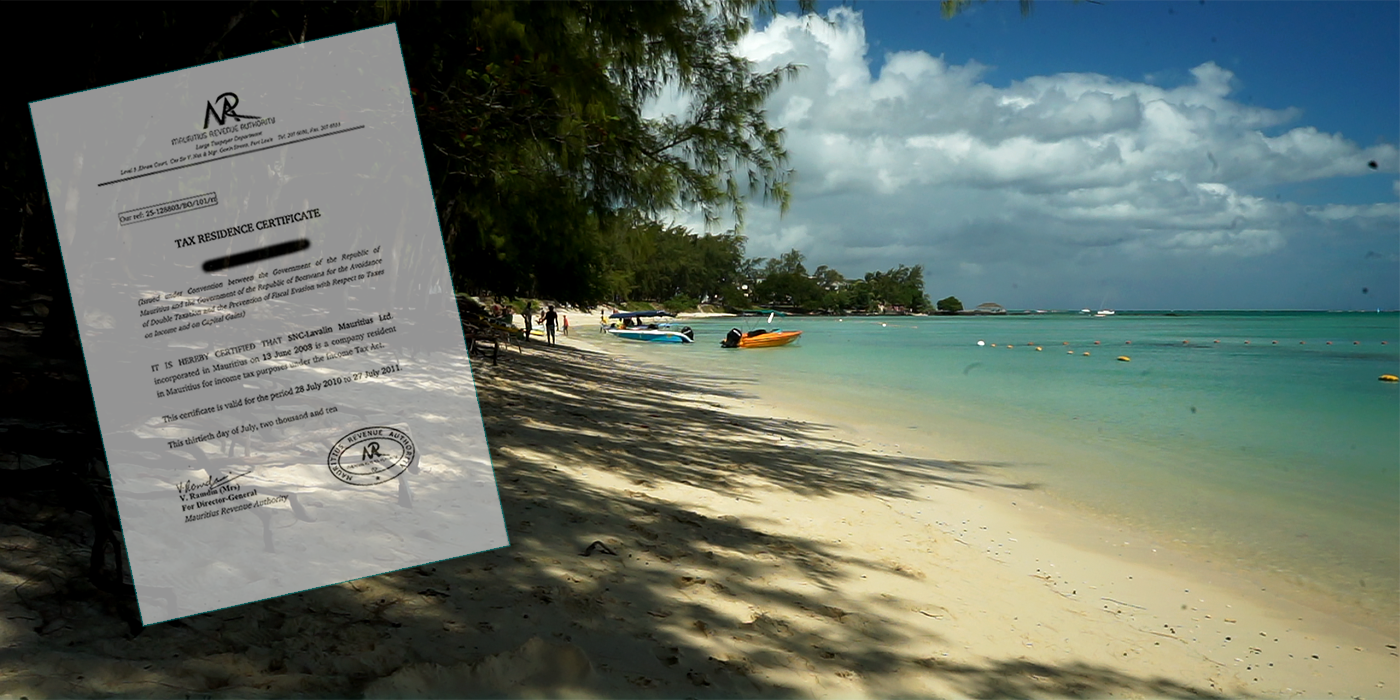

The companies behind the New Dawn Satellite channeled millions of dollars in payments from African companies and governments through offshore companies in Mauritius, one of the continent’s premier tax havens.

In so doing, the companies achieved a Mauritian double-whammy, using one kind of offshore company to avoid local taxes and another to pay as little as possible on bills paid from overseas using treaties signed between Mauritius and its African neighbors.

The primary money-making company estimated that it would pay $22,500 in taxes on $75 million in revenue – just 0.03 percent.

In a 17-year lifespan, the company predicted, it would earn $936 million yet never pay taxes above $300,000.

That’s according to a PowerPoint presentation from the Paradise Papers, offshore documents that include nearly seven million files from the law firm Appleby and its clients, including the satellite’s co-owner, Intelsat.

“The purpose of the tax structure is to drastically minimize the tax exposure of the company and pay as little as possible, which the company has successfully achieved,” said Alexander Ezenagu, an international tax researcher with International Centre for Tax and Development, who analyzed Intelsat’s documents.

The Mauritius arrangement lasted until 2013 when Intelsat closed the companies down after unexpectedly low financial returns. The company’s tax return that year reflects that it paid 0.09 percent tax on $31.6 million.

Intelsat told the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists that it “has a proud history of serving the African continent, providing vital connectivity and access to world-class technology since the late 1960’s.” It said Mauritius was chosen “in concert” with its South African investment partners.

“We pay taxes where we have established a taxable presence, such as our regional office in South Africa,” Intelsat said. “Where we do not have a taxable presence, in nations where applicable, our services are taxed through withholding taxes, which are paid on our behalf by our customers under our contractual agreements.” According to other tax experts, though, those payments are unlikely to be made.

The New Dawn project was terminated in 2013 “following a major satellite anomaly that irreparably reduced the commercial viability and financial returns expected from the project,” Intelsat said.

Though not a household name, Luxembourg-based Intelsat’s technologies are behind some of the 20th Century’s most enduring memories.

Intelsat’s satellites, for example, allowed millions to watch the 1969 moon landing and the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Its satellites cover 99 percent of the world’s population, allowing cell phone and internet providers to offer phone calls, online surfing and television.

In 2008, Intelsat announced plans to launch the New Dawn satellite, its first with an African focus.

The satellite, built in Virginia, used channels or “transponders” that helped send information via antennas to earth.

For years, governments and the private sector have salivated at prospects for Africa’s development – if only there were improvements to the continent’s communication black holes.

Intelsat used the Appleby law firm and accounting firm KPMG to establish the Mauritius companies behind the New Dawn satellite.

Intelsat’s Bermuda-based subsidiary and South Africa’s Convergence, a consortium of largely African investors, were initial investors. (Convergence left the partnership after one year.)

Following the satellite’s 2011 launch and the first customer orders, the African tax haven strategy proved lucrative, according to dozens of invoices, tax returns and financial statements from the Paradise Papers.

Nearly all New Dawn’s income came from cell phone and satellite companies, including Airtel, one of Africa’s major providers. Namibia’s government-owned telecommunications company, Telecom Namibia, and South Africa’s state-owned signal distributor, Sentech, were also customers.

Airtel’s subsidiaries paid Intelsat’s Mauritius-based company, New Dawn Distribution Company Ltd. for services in that included Sierra Leone, the Republic of Congo, Chad, Gabon, Madagascar, Niger and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – then the poorest country in the world. Some contracts brought in $100,000 a month.

In 2012, for example, Intelsat’s Mauritius company sent a bill to Airtel in the Republic of Congo for $201,000. Under a 2011 treaty, the Republic of Congo agreed to waive taxes on its domestic companies worth up to 20 percent on the value of services provided by companies in Mauritius, such as Intelsat’s. In this one invoice alone, then, the Republic of Congo could have forgone up to $40,000 in taxes on the $201,000 bill paid from the client to Intelsat’s Mauritian shell company.

Intelsat did not respond to ICIJ’s specific questions about whether or not it its customers paid reduced or no taxes under treaties. It told ICIJ that, in general, “we pay withholding taxes, where required, through contractual terms with our customers in the countries where the services are being consumed.” Airtel declined to comment.

“That’s exactly the problem,” said Alvin Mosioma, executive director of Tax Justice Network – Africa, who described telecommunications companies as “one of the major culprits on the continent when it comes to aggressive tax avoidance.”

Using treaties in this way, Mosioma said, “shifts the responsibility to the telecommunications companies.”

I would honestly think, by now, that tax treaties with Mauritius should have become discredited.

The end result, Mosioma said, is that some taxes might not be paid at all. Treaties such as the one signed between the Republic of Congo and Mauritius could have allowed Intelsat to avoid or reduce tax in Mauritius and could have scrapped some taxes entirely in the Republic of Congo that would, without a treaty, be paid by Intelsat’s customer.

Financial and company laws in Mauritius, researcher Ezenagu says, “are structured to provide tax advantage to companies at the detriment of countries where the real economic activities occur and value is created.” Intesalt’s structure “takes advantage” of these laws, Ezenagu said.

“I would honestly think, by now, that tax treaties with Mauritius should have become discredited,” he said. “They simply do not grant the benefits to the countries that they were told they would.”