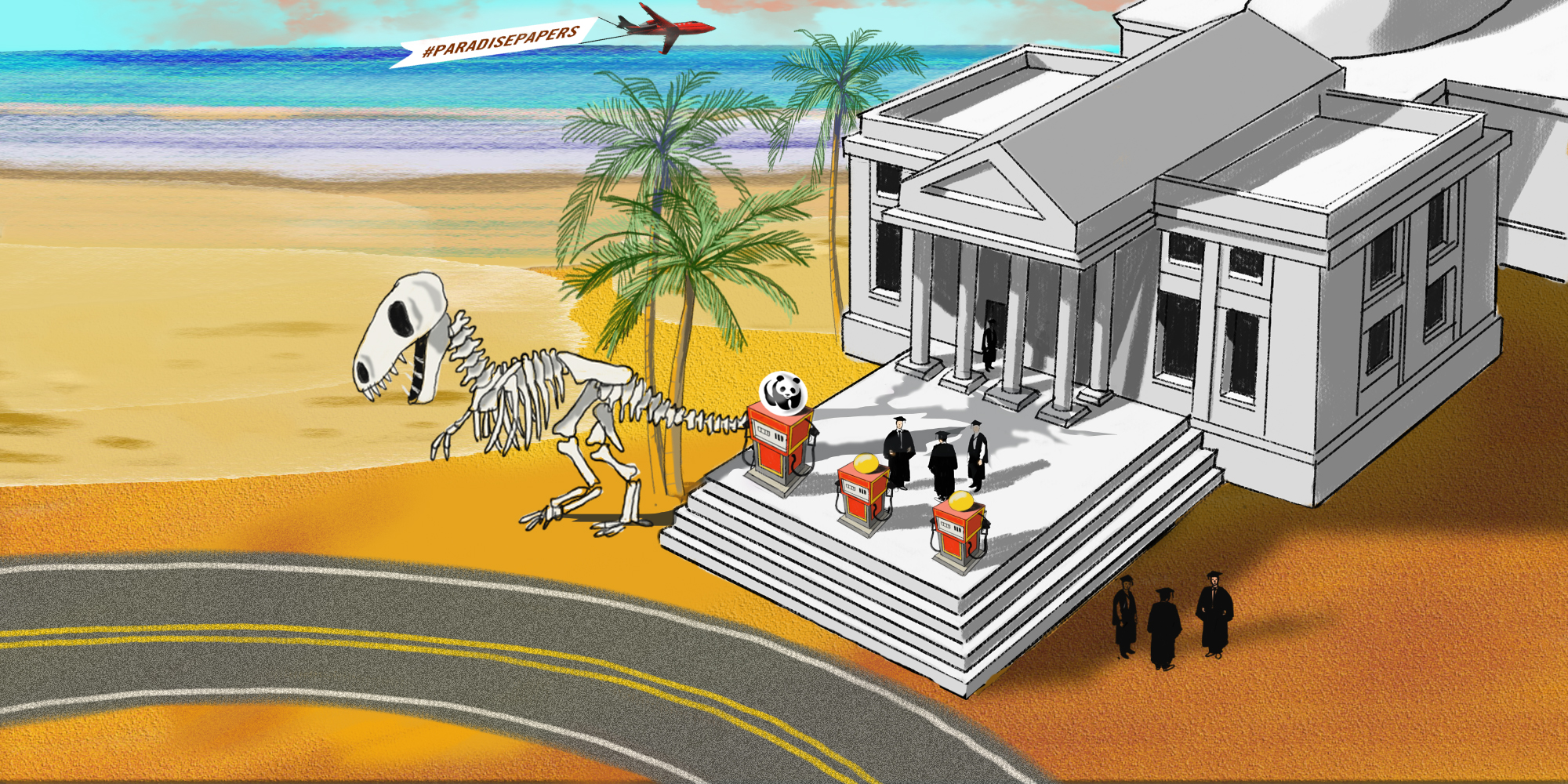

From a 34-foot tall Tyrannosaurus Rex skeleton to a herd of taxidermy elephants forever poised to charge, the American Museum of Natural History is a celebration of nature. Through its exhibits, website and other public education efforts, the New York City institution regularly encourages conservation and protecting the planet from climate change.

But, at least since 2009, the museum’s endowment fund has quietly invested millions in the oil and gas industry through an undisclosed stake in a private equity fund, reveals a report by NBC News, which joined the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists in a new Paradise Papers investigation examining the offshore investments of nonprofit organizations.

The museum invested $5 million in a fund run by Denham Capital, a private equity firm that invests in oil and gas, mining and power plants. That fund has pumped money into fracking for shale oil in Ohio and Pennsylvania and made an unsuccessful bid to invest in coal in Mongolia.

The museum is one of several prominent environmental nonprofits and foundations, including the World Wildlife Fund, whose investments in fossil fuels were uncovered by NBC and other partners in a collaboration with ICIJ in a new look at the Paradise Papers, a leaked trove of 13.4 million documents, obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with ICIJ. The files revealed how endowments, foundations and other nonprofits use offshore companies and undisclosed investments to obscure where their tax-exempt dollars are flowing.

The investigation showed nonprofits repeatedly making investments that contradict their missions and lobbying in state legislatures to increase the secrecy surrounding their investments.

NBC’s findings are part of a collaboration, dubbed Alma Mater, organized by ICIJ to examine the offshore investments of U.S. tax-exempt charitable organizations. Originally designed to investigate more than 100 universities whose endowments appeared in the Paradise Papers, the project expanded to include nonprofit museums, foundations and advocacy groups. It includes reporters in California, Montana, New York and Tennessee, working for outlets ranging from national television networks to city newspapers to an independent university publication.

Among the most striking findings were the investments by environmental groups in the fossil fuel industry. Not only the American Museum of Natural History, but also World Wildlife Fund, which states publicly that “we must urgently reduce carbon pollution,” invested in the Denham Capital fund, NBC News found.

The museum told NBC News that the investments represent “a small part of our overall program for managing the Museum’s endowment” and has noted in the past that it holds no direct stock in fossil fuel companies. It has been working since 2014 to reduce its fossil fuel investments. The World Wildlife Fund told NBC News that it is trying to unwind investments in oil and gas, and that, in the meantime, it has put money into a counter investment offered by a Deutsche Bank financial instrument which loses money when fossil fuel stocks rise and earns money when they fall.

While the museum and the World Wildlife Fund are working to cut back their investments in fossil fuels, other nonprofits have resisted.

A major foundation that supports environmental causes, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, has also turned to the energy sector. The Packard Foundation invested $50 million in a fund managed by U.S.-based private equity firm Energy Capital Partners that invests in oil and gas-related operations, NBC News found.

The Packard Foundation, which states on its website that it “invests in policies and projects to transform the use of fossil fuels around the world” with its grants, told NBC News that when it comes to its endowment it seeks to maximize gains on its investments and does not avoid fossil fuels.

Universities that have taken public stances in the fight against climate changes have also behaved differently when it came to investing their endowments. Earlier this year, the University of Washington was one of 13 universities that formed the University Climate Change Coalition, an initiative to reduce carbon emissions. Yet it invested $9 million in the Denham Capital fund, NBC News noted.

The University of Washington told NBC News that it had resolved in 2015 to divest from coal, but not from other fossil fuels.

The University of Montana, which has not made similar public pronouncements about climate change, also has invested in fossil fuels. The University of Montana Foundation sent $5 million in 2007 to a fund operated by private equity firm Coller Capital, which in turn invested in a joint venture including Royal Dutch Shell, reported the Montana Kaimin, the University of Montana’s independent student newspaper.

In a previous interview with the Montana Kaimin, University of Montana President Seth Bodnar declined to commit to divesting from fossil fuels but expressed openness to considering social responsibility in judging investments.

The University of Montana Foundation has invested more than $30 million in offshore funds, the Montana Kaimin reported.

Universities go offshore

Investments in private equity firms that finance the oil and gas industry are part of a broader shift in how universities manage their endowments. The search for higher returns has led universities to move away from traditional stocks and bonds and focus on “alternative investments,” which include hedge funds, private equity funds and venture capital.

The University of Tennessee’s turn to offshore alternative strategies includes shares in at least 19 funds with a combined value of more than $200 million as of June 2017, reported ICIJ’s partners at the Memphis Commercial Appeal. These investments represent about 20 percent of the endowment, while its investments in U.S.-based stocks and bonds has dropped to about 5 percent, the Commercial Appeal found.

Overall, the percentage of university endowments in alternative investments jumped from 20 percent in 2002 to 51 percent by 2014, according a 2015 report by the Congressional Research Service.

The push for secrecy

As they have embraced alternative investments and tax havens, some universities have also pushed to keep the activities of their endowments secret. Public universities, which are subject to Freedom of Information laws, have taken some of the strongest steps.

Last year, the Board of Regents of the University of Montana System, comprised of sixteen universities and colleges across the state, signed a new contract between the system and the foundation that manages its endowment. The contract included language allowing the foundation 20 days to block public records requests to the university system in order to seek a protective order, the Montana Kaimin reported.

The University of Tennessee also acted last year to keep its endowment’s activities secret. The university successfully lobbied the state legislature to pass a law allowing the university not to disclose the fees that it pays to the funds that invest its money or the identity of the companies that these funds ultimately invest in, reported the Commercial Appeal.

University of Tennessee Chief Investment Officer Rip Mecherle told the Commercial Appeal that its offshore investments were above board and “plain vanilla.” He said that he had personally helped draft the secrecy provision at the request of the university’s money managers and that some of the best investors insist on such secrecy rules as a condition of accepting a client.

Even without new secrecy provisions like those in Montana and Tennessee, universities and other nonprofits face little scrutiny as they seek to maximize returns on holdings as large as tens of billions of dollars. Sometimes the investments conflict with goals the tax-protected institutions have publicly embraced, the Paradise Papers revealed. More often, the destination of these tax-exempt investments remains hidden from view.