Rummaging through the records of offshore havens turns up a fairly predictable list of assets – real estate, cash, earnings shifted to low-tax jurisdictions by multinational companies, hidden masterpieces by Picasso and other artists, antique cars, yachts and planes.

But musical memories? The songs that you danced to in your youth or at your son’s or daughter’s wedding? The summertime hit you sang driving down backroads or the reggae tune blasting at the beach? What are they doing offshore?

They’re there for the same reason as other assets – tax advantages. Skipping taxes increases earnings from intellectual property – patents, copyrights, trademarks and trade secrets – as well as other holdings.

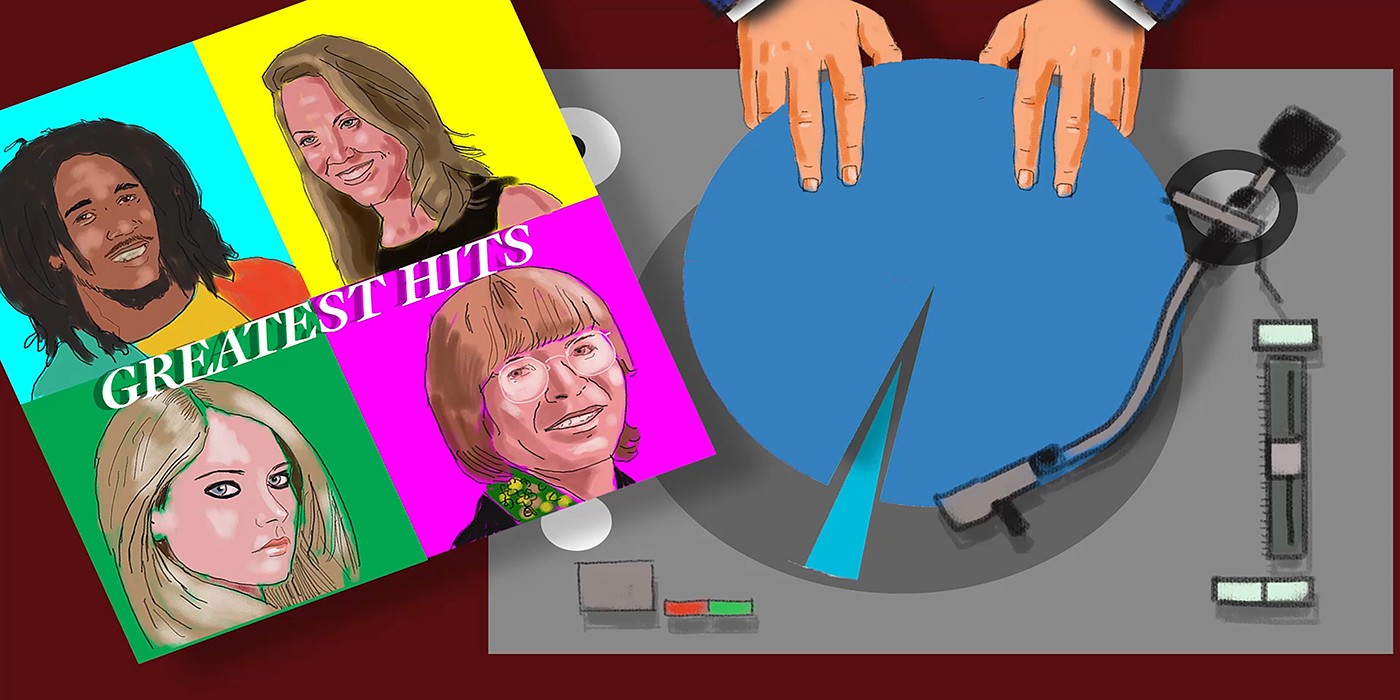

Files from the Appleby law firm office on the island of Jersey, in the English Channel, include a cache of music publishing rights, a stream of royalties to be collected for music produced by artists that included John Denver of “Country Roads” fame, Duke Ellington, Chubby Checker (not your usual Jersey Boys) and Sheryl Crow.

It’s a music catalog, held until 2014 by a Jersey-registered company and originally managed by a company registered in Ireland. Why Jersey? Its standard corporate tax rate is zero.

Music publishing rights have retained value despite turmoil in the industry that has eroded the worth of related rights and caused a steep decline in royalties from sales of vinyl records and compact discs.

The universal language

“There is a burgeoning market for music catalogs among institutional investors who are looking for fairly reliable revenues in the future,” said Chris Hayes, an economist at the research firm Enders Analysis, which specializes in media, entertainment and telecommunications. Publishing rights generate income from a diversified pool of sources that includes, among other things, licensing the music to gyms, bars and even ringtone services.

The market’s steadiness has attracted new institutional investors, including pension funds. And, just like the owners of other valuable commodities, owners of music rights have looked to maximize value by stashing money-making music where the earnings flow tax-free.

It is not surprising that music publishers would want to go offshore. There is “a global structure in the music industry with national laws that are very different from country to country,” explains Luiz Augusto Buff, a Brazilian specialist on the industry. “But the users are global so that tends to make sense, with that much international transactions happening, to try to find a more efficient strategy tax-wise.”

If the owner plays it right, music catalogs can be real moneymakers. “The music publishing industry generates around $6 billion a year globally,” according to a 2015 analysis in the Berklee College of Music’s Music Business Journal. Every time a song is used in a movie or on TV, in a video game, on the internet or sold as sheet music, the owners of those rights cash in.

The Trammps’ 1976 “Disco Inferno” was the Jersey catalog’s most profitable song in 2009 and 2010, producing royalties of more than $600,000.

The owner of the catalog-owning Jersey company, First State Media Works Fund I, attracted investments from pension plans in North America, Europe and Australia. It created the Jersey subsidiary FS Media Holding Co.(Jersey) Ltd. as an investment vehicle, which was managed by First State Media Group (Ireland) Ltd. (FSMG) acting as a publisher – promoting the songs on behalf of songwriters, the way a label would for records.

Steve McMellon, former managing director of FSMG and now director of Southern Crossroads Music, did not respond to ICIJ’s repeated requests for comment.

The subsidiary was set up in 2007 specifically to acquire music rights. In July 2009, Crow sold the rights to 153 songs written between 1993 and 2008 to the Jersey company for about $14 million. The package included chart-topping hits “All I Wanna Do” and “My Favorite Mistake.”

Crow did not respond to requests for comment.

In April 2010, FSMG, the Irish company managing the catalog, was acquired by the U.K. media company Chrysalis PLC for about $16.8 million. The sale did not include the catalog. The combined companies were acquired by Bertelsmann Music Group less than a year later for $168.6 million. Steve Redmond, head of communications for BMG, said the company had been offered the catalog but did not acquire it. “We merely inherited a company which had a deal to manage those assets on behalf of the owners.”

In time the catalog owned by First Media grew to a collection of 26,000 songs from the last seven decades.

An offshore failure

The Jersey company continued to make money on royalties from Ellington’s “Day Dream,” Bob Marley’s “Get Up, Stand Up,” Avril Lavigne’s “Nobody’s Home,” Kelly Clarkson’s “Because of You” and others. From 2010 through 2012, it made on average $4.6 million a year in royalties.

And, in a 2013 overview written for its proposed sale, the catalog was described as “one of the larger aggregations of copyrights to have been recently available on the market.”

We have assumed the tax structure position of the Company as an off-shore tax structure whereby no tax is payable on income generated by the Catalogue.

The review of the Jersey company by the accounting firm KPMG also noted its tax advantages. In the first half of 2012, 68 percent of the royalties earned by the publisher – after paying writers, copyright-collection societies such as ASCAP and BMI, commissions and charges – came from the United States. Yet FS Media Works Fund I, an English limited partnership, paid no taxes in the United Kingdom, according to KPMG, and was not subject to U.S. federal income tax. Nor was there withholding tax associated with the catalog.

“We have assumed the tax structure position of the Company as an off-shore tax structure whereby no tax is payable on income generated by the Catalogue,” the accounting firm observed.

KPMG declined to comment on details of these reports but underlined that “they were prepared not in connection with tax, but as a basis for the valuation of certain assets to be included in the company’s financial statements.”

Despite the tax savings, things weren’t looking good for the catalog sale. Making money also requires good marketing.

An even earlier analysis by accounting firm PwC in 2011 found that the portfolio dropped more than half of its value in a single year – to $75 million in 2010 from $153 million in 2009. The 2013 KPMG analysis confirmed a decline in value of the catalog’s assets, underlining that the biggest drop came from the Sheryl Crow tunes, which suffered a 24 percent loss. “Changes in ownership . . . over the past three years have led to a lack of marketing of the Catalog and the copyrights have been under-exploited as a result,” according to a 2013 “teaser” to attract investors.

Documents show that FS Media Works Fund I was struggling to pay back $19 million still owed to the Royal Bank of Scotland on a loan taken out in 2009. The catalog ended up being sold in 2014 to Reservoir Media Management Inc., which declined to comment. The company, an independent music publisher based in New York City but incorporated in Delaware, acquired it for $38 million – about a quarter of its value five years before.

It sold for a song.