This story is part of ICIJ’s Paradise Papers investigation. Today, we’re releasing more data to our Offshore Leaks Database – so you too can explore the millions of offshore records.

Late afternoon was snack time at TLC Supported Living Services, a care home for people with developmental and physical disabilities between two Native American reservations in Show Low, Arizona.

In July 2015, at the peak of summer, a TLC caregiver was feeding orange slices to Marsha Campfield, a smiley 23-year-old who lived for puzzles, bracelets and rounds of Frisbee with her father.

Before the clock struck five, the caregiver started to make a phone call and looked away.

As the caregiver did, Marsha’s parents later alleged, an orange wedge with some of the peel still attached became lodged in Marsha’s windpipe. She choked, blacked out and died.

The risks of injury, death and lawsuits were something that TLC’s owner, Doug Kaplan, was not entirely unprepared for.

A former client had previously sued one of his healthcare facilities for alleged negligence and abuse.

The case was dismissed in 2006, but Kaplan later took steps to protect himself from any adverse court judgments or jury verdicts.

Breakfast in Phoenix

He started with a breakfast meeting with a lawyer in Phoenix the following year.

Joining them was Adrian Taylor, the laconic managing director at the Cook Islands branch of Asiaciti, a firm specializing in offshore companies and trusts.

Kaplan told Taylor that he was about to open a high-risk care facility for mentally disabled patients. Another source of Kaplan’s concerns was a dispute with former employees who claimed unpaid overtime. Kaplan was confident of a settlement, he told Taylor, but worried it could “open the floodgates” for hundreds of others.

Kaplan and the lawyers mulled over “worst-case scenarios” for either of those concerns, according to notes of the meeting. Would a trust in the Cook Islands protect his current wealth, Kaplan asked. What about money he made in the future. Would that be safe, too? How easily could a court break his trust?

Asiaciti’s Taylor reassured the Arizona business owner and “gave him the usual ‘peace of mind’ responses.” About two months later, Kaplan had a trust whose name reflected more the ecosystem of its Pacific Island home than his business’ location in Arizona: Coral Reef.

Kaplan told ICIJ that he created the trust for different reasons, including a desire to protect his savings from “frivolous claims” and “predatory lawyers.”

Kaplan said that, ultimately, he changed his mind about starting a new venture in Arizona held by the trust. Both the company and the trust, he said, were “empty” shells that never held any money, bank accounts or signed any deals.

“The Coral Reef Trust was intended to be for my personal assets and had nothing to do with TLC,” Kaplan said.

Kaplan’s business was one of many successes that followed Taylor’s 12-day trip across the continental United States. The details of the 2007 tour are contained within “marketing visitation” reports, two of the 13.4 million files contained within the Paradise Papers.

If someone has an offshore trust, it’s extremely difficult and expensive for people to get to it.

Asiaciti is a well-known player in the international trust circuit and serves some of the world’s wealthiest and highest-profile investors and moguls. The U.S. tours continued into 2015.

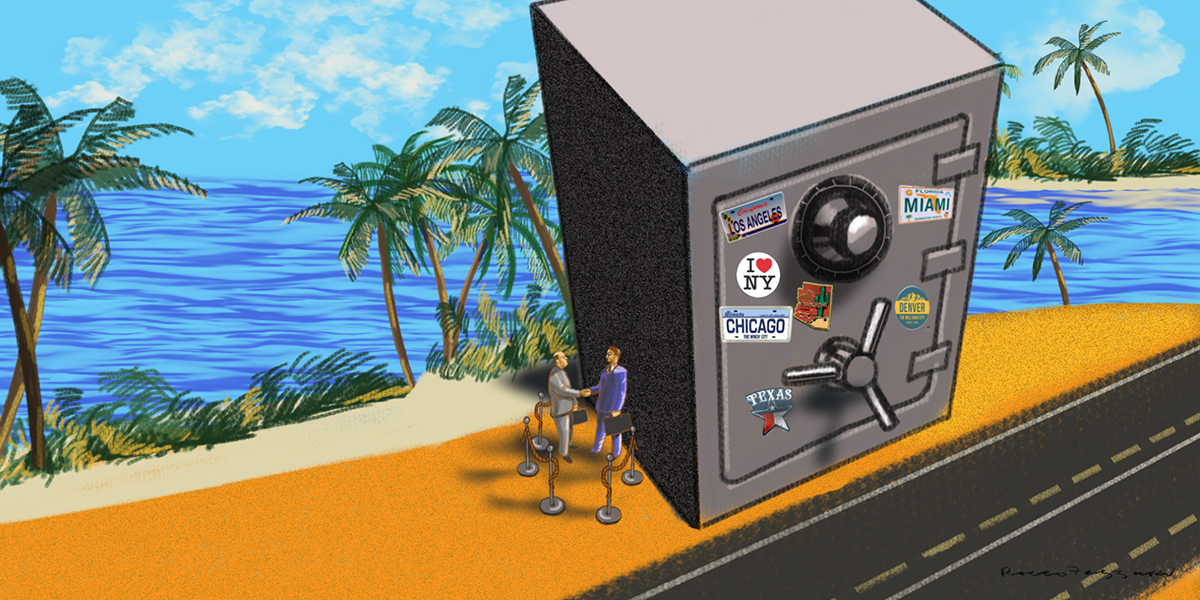

One of the company’s specialities is the creation of Cook Islands trusts – hard-to-pierce safe holdings used to manage wealth and assets. Though prized by the rich, the publicity-shy and, in some cases, the fraudulently-inclined, they are viewed with suspicion by investigators, tax collectors and law enforcement.

While offshore trusts can be innocuous tools for parents to safeguard their children’s inheritance or for pet owners to indulge their favorite tabby cat or fluffy dog, judges have sentenced and jailed Americans who used trusts to frustrate creditors, block legal orders or hide ill-gotten gains.

While rules have tightened since 2007, including the addition of disclosure requirements to the Internal Revenue Service and European Union rules that require countries to collect trust owner information, offshore trusts remain largely impenetrable.

“If someone has an offshore trust, it’s extremely difficult and expensive for people to get to it,” said Jay Adkisson, a California attorney, author and expert witness.

For many, says Adkisson, the thought of moving money offshore makes them feel “a little like James Bond.”

Lunch in New York City, Dinner in Miami

Asiaciti’s U.S. tours were valuable entrees into North America, a market teeming with what experts call the “lower wealthy” – clients with a few million dollars to spare.

Asiaciti executives made two trips across the country in 2007 with packed schedules that included lunch at a private members’ club in New York City, homespun dinner in Miami, a meet-and-greet at a family office in Denver and parlays with Texas representatives of a major American bank.

Taylor and Asiaciti did not respond to questions but referred ICIJ to a previous statement in which it said the company complies with applicable laws and regulations and denies “any implication of wrong doing.”

While not every meeting ended in success (some were dismissed as “WOFT” for “Waste of F****** Time”), new clients included a Texas landowner who wanted no one to know that he leased land to an oil company and a pair of Los Angeles-based motivational speakers.

Some Americans Asiaciti courted in 2007 already had reasons to seek refuge from U.S. laws. Others would face investigations in the years to come.

Kaplan, of TLC Supported Living Services, for example, had made his money in health care in Indiana and the Grand Canyon State, including the home in eastern Arizona where Campfield died.

Employees and clients sued Kaplan’s companies four times, according to public records. In one case, a former employee sued for $5 million and alleged he was fired for refusing to falsify documents. A former client claimed that the company subjected her to physical abuse. The cases were settled and dismissed, respectively. Kaplan said he strongly disputes allegations that anyone was asked to falsify documents and contested the other allegations of wrongdoing.

In January 2017, Campfield’s parents resolved the case out of court with TLC and other defendants, who denied wrongdoing. The suit did not name Kaplan personally.

“TLC has always carried significant liability insurance for these types of claims,” Kaplan said. “The case was settled by the insurance company with a payment to Ms. Campfield’s family.”

Kaplan told ICIJ that the Coral Reef Trust was terminated in 2014 and had no role in the lawsuit over Campfield’s death, which he called a “tragic accident.” The Campfields did respond to requests for comment.

Last stop: Chicago

On a mild morning, almost two weeks after meeting TLC’s Kaplan and after stops in five other U.S. states, Asaiciti’s Taylor was in Chicago for the last day of his tour.

By lunchtime, Gregory Bell, a computer science graduate with an MBA, was a satisfied new client, meeting notes recall. Bell created the Blue Sky Trust in the Cook Islands in July 2008 and handed it control of a Swiss bank account.

Two months later, Bell’s life unravelled when FBI agents raided the home and office of his business partner, Thomas Petters.

U.S. officials accused Petters of fraud and money laundering central to a $3.7 billion Ponzi scheme that was the largest in U.S. history at the time. Single mothers and retirees who invested half a century of savings were among the victims. Petters was charged in October that year and sentenced in April 2010 to 50 years in prison for orchestrating the massive fraud.

“Almost any time there’s a sizeable Ponzi scheme, there are allegations people are taking some of the money offshore,” said Kathy B. Phelps, an attorney who co-wrote “The Ponzi Book.”

While trusts are not unbreakable, Phelps said, victims and enforcement agencies can struggle to find them or even know they exist. “And once you’ve done that,” Phelps said, “there’s the question of whether you’ve got the cooperation” of the country where the trust is created and of the lawyers who helped set it up.

In 2009, the Securities and Exchange Commission filed fraud charges against Bell and his Illinois hedge fund. While he wasn’t central to the underlying fraud, authorities said, the SEC complaint alleged that Bell was “blinded” by multimillion-dollar fees he earned from it and misled investors about Petters’ background and the details of the scheme. The SEC named Asiaciti’s trust arm as a co-defendant and Asiaciti’s Taylor, who met Bell in Chicago, supplied affidavits in criminal and civil cases that were helpful to the case against Bell.

U.S. authorities alleged that Bell moved $15 million to his Cook Islands trust to avoid creditors and the government. Authorities said they wanted to recover millions of dollars “before the money disappears overseas.”

Asiaciti’s files show that Bell made insistent evening phone calls and a fax to lawyers in July 2008 as the Ponzi scheme neared collapse.

“Mr. Bell is anxious to submit the applications, and I would like to provide him with an update tomorrow,” Bell’s American lawyer wrote about paperwork needed to open a bank account.

Bell was arrested in July 2009 and pleaded guilty to intentionally defrauding investors. He helped return the $15 million to the United States and was sentenced to serve 72 months in prison. Contacted by ICIJ, Bell declined to comment.

Asiaciti also cooperated with U.S. authorities, and the company was never charged.

But it could never quite shake its involvement.

Once, emails show, Asiaciti struggled to persuade a bank where it was hoping to help open a client’s account that it bore no responsibility for the fraud into which it was ultimately drawn after meeting Bell in Chicago all those years ago.

Said Taylor about the bank’s hesitation: “Un*******believable.”